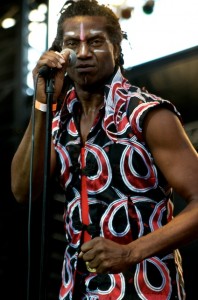

Antibalas—America’s pioneering Afrobeat band—emerged out of Brooklyn in 1998 and have since traveled the world spreading the Afrobeat gospel. For the past 5 years, core members of the band have played in the pit band for the equally-globetrotting Broadway musical Fela!, which tells the story of Afrobeat’s founder Fela Anikulapo Kuti. Now that Fela! is winding down, Antibalas is back, with a heavy tour schedule and a new, self-titled CD on Daptone Records. Daptone was created by Gabriel Roth, an Antibalas alumnus who engineered the new recording. On August 18. 2012, Afropop’s Banning Eyre caught up with the band at a show in Williamsburg Park in Brooklyn, not far from the band’s old stomping grounds. He spoke with lead singer and percussionist Abraham Amayo and guitarist Marcos Garcia. Here’s their conversation.

Banning Eyre: Let me start by asking about what it's been like getting the band rolling again after the Broadway show.

Banning Eyre: Let me start by asking about what it's been like getting the band rolling again after the Broadway show.

Marcos Garcia: It's kind of like when you wake up in the morning and your kind of groggy and it takes a little while to get the crust out of your eyes and then stretch a little bit, and then once you get up, you start moving. And we all move together. It's like one big monster.

Abraham Amayo: Yup. Just like that. Did you see that movie The Avengers? In the opening there were these giant monsters, air serpents. Like sea monsters in the air. That's how we are, like air monsters put into the vortex. (LAUGHS). But to add to that, for me, anyway, I was looking forward to a break from Antibalas, because we had already been on this amazing run.

M.G.: We had been on the road for a long time.

A.A.: A long time, so I was looking to take a break. Some of us had the opportunity to move onto a new project. I have this project called Fu Orchestra that I was also trying to complete. I went to Brazil. I came back broke. Unemployment—the whole gamut. Used up all the savings. And I have a baby now. So all that time the Broadway show was going on, I was creating. I was co-creating.

B.E.: What's Fu Orchestra about?

A.A.: Fu Orchestra. It's Kung Fu meets Afrobeat. So I was teaching martial arts, boot camp. Kind of recharging the body a bit.

B.E.: Marcos, you have your own band as well, Chico Man. Were you focusing ont hat, or were you involved in the Broadway musical?

M.G.: Well I was involved in the off-Broadway portion of the musical. And then once it went to Broadway, I kind of took that as my cue to devote my energy to Chico Man, and to developing my own thing.

B.E.: Let’s talk about this new Antibalas album, the first recording in five years. Aside from getting back in the swing of things, was there any particular concept or goal for this record?

B.E.: Let’s talk about this new Antibalas album, the first recording in five years. Aside from getting back in the swing of things, was there any particular concept or goal for this record?

M.G.: Well, I think when it worked out that we were gonna work with Gabriel Roth and we were gonna record at Daptone, it was clear what the aesthetic was gonna be, so then it was kind of easy then to move forward creatively. We had some old songs that needed to be recorded, and then some new stuff. So what was it like? The word that keeps coming up for all of us as "homecoming." Because we had all spent time there, it was really nice to be in familiar territory even if we didn't know what we were aiming for going in. It was just kind of a relief in a lot of ways, especially when you have that many people and everyone's got their own aesthetic things happening. This is kind of like our common ground, that Daptone sound.

B.E.: How would you describe that sound to someone who didn't know it?

M.G.: Analog.

A.A.: Bed-Stuy. Backroom. Basement. That kind of sound that you hear in the city alleyway, or someone's backyard. It has all that. Because literally, the studio is just like that.

M.G.: Yeah, it's called flavor.

A.A.: For me, the energy leading up to this record... You know, because I was at Dunham Studio, Daptone’s sister studio, trying to complete some of my old recordings from Fu Orchestra, which Gabe had engineered back then. So we found all these reels. So in the horn section, it galvanized some old excitement, you know, like "We got to get back to some of the old stuff we were doing." So I think I had an added yearning to get back and get something out. It was perfect timing. Like Martin [Perna] says, "Out with the old in with the new."

B.E.: I’m going to throw out a few song titles from the new record, and you can just tell me anything you want about that song—anything you think is interesting about the music, the lyrics, the message, whatever. Let's start with the opening track "Dirty Money."

A.A.: Well, I could say that for me that's kind of like a billboard to keep that whole Occupy energy going. It's time for the youth to start taking that position of accountability.

M.G.: I think it's more than just the youth. I think it's time for everyone in this country and around the world to take accountability for themselves, and kind of the decisions that we make as consumers and how that contributes to the corporate dominance of governments all over the world. I don't think anyone really likes that, but at the same time everyone likes having their cheap Wal-Mart stuff. Our actions and our decisions are key to feeding the system, and if we want to change it, the only way to do that is to make conscious decisions about where you shop. It kind of boils down to something as simple as that.

A.A.: Bottom line, yeah. Because all money is dirty. You know that somehow, somewhere, it's all coming from that oil money. It's sifted down through everyone's hands somehow. It's what you do afterwards when you get this money that's affecting change.

M.G.: I think of it differently. I don't think of money as dirty necessarily. It's an inanimate object. What makes it dirty is what people do with it. And it always goes back to your own individual choices, and how you spend your money. It's like a necessary evil, as they say. But it's really about what we do with it.

A.A.: I agree with you on one level, Marcos. But on another level too, I don't think we should just assume that things don't have energy. Everything has energy. Money especially!

M.G.: Well, absolutely. But it's how you use that energy, right? I mean, I don't necessarily think that it's negative or positive. It is energy, it comes, and goes, and flows. It's what we do with it and the intention behind it that determines whether it's positive or negative.

B.E.: Wasn't it Norman Mailer who had that famous quote about how there is no money that isn't morally contaminated somehow or other? I thought about that when I was checking out the lyrics to this song, because it's talking about situations where someone is in immediate trouble, and somebody's idea of how to help is to just throw money. But that money is never reliable.

M.G.: Right, it doesn't float. LAUGHS

A.A.: You know, the lyrics are right there. And then you can go deeper into all the energy aspects about money, and what actually moves everything.

B.E.: I am curious about your creative process. Let's just take that song. I imagine that started with music, maybe a jam session, and then it turns into a song. How does that happen?

A.A.: For this song, in particular, it took a long process. Conversations. We've had many talks like the one we were having just now. We've had this many times. I remember one time I was having a talk with our old drummer. We were on tour and we were driving together, and we were talking about intention, the intent behind money, and the idea that money actually has no value—it's we who apply the value to it. So from all those kinds of conversations, there are words that just sound very appealing to make a song more captivating. So that part came together rather quickly. Luke might say a couple words. It doesn't really rhyme. Then someone will throw a line at me...

M.G.: So how did the words for "Dirty Money" come about?

A.A.: Well, first I had the hook thing I was hearing in the control room. I was trying to write these words and pacing back and forth. I had that hook. "Dirty money no dey float" part. Now, where does that float part actually build up from? So we needed a line, and it had to fit within that space. I took one word out. I think Luke added the line from the second verse when we couldn't figure out where to move from when we toss him the rope of money. I came up with the concept of kind of visualizing that you could toss a rope of money. Money can become a rope. So that's how the words spilled out. You have to find the words to make the idea more effective.

M.G.: I didn't realize you actually wrote the lyrics in the studio. You see, there's so many of us. It's like taking shifts, you know? We might not always be in the same place at the same time until we get on stage. Especially with recording. Actually, we got the rhythm section together, and then after the rhythm section was done, I don't know what happened.

A.A.: People kinda walked away, and I was there in the studio, and Gabe says, "So, Amayo, what you got going on?" And I said "Well, I got a hook…"

M.G.: See, I didn't even know that.

B.E.: So there's a lot of creation going on in the studio. And that's not necessarily typical when a band records a record.

M.G.: It always depends, though. It's not always like that in the studio. There's plenty the times we’re work-shopping something in rehearsals, and then we'll get it almost all the way together, and it just takes being in the studio to cement or crystallize the idea and say: this is it.

A.A.: It's also the pressure of that moment of delivering.

M.G.: Yeah, it catalyzes you.

A.A.: It’s like I was saying about those conversations, when everything comes together. You gonna lay this down now. It just gels.

B.E.: What about "The Rat Catcher"?

M.G.: That's been in the rotation for a while. Who knows? It's kind of a mythological creation by now.

A.A.: Yeah, we been chasing that rat a long time.

M.G.: It's changed a lot too, like the form of that. The lyrics have stayed.

A.A.: Yes, the lyrics are the same. I have a ranted over that song so many times, so it became more concise.

M.G.: And I remember we were rehearsing that song in Manchester, England. We were there for a week, and we spent about a week rehearsing before we were playing like five nights in a row or something. That was a long time ago.

B.E.: That was the pre-Broadway days.

A.A.: Oh yeah. That has never happened in a while. To have five days to work on new things.

M.G.: But I remember we were developing that one, and "Government Magic." All this stuff that came post Who Is This America [2004]

A.A.: Some of the songs are on this new CD had already been in rotation. I think "Dirty Money" is the only really new one.

B.E.: What about "Him Belly No Go Sweet"?

A.A.: Well, that song is just talking about how it's tough for a man to be happy if his woman ain't happy. If your woman ain't happy then you're not gonna be happy. Just a matter of reaching out to the sensitive part of the man to realize that the woman actually got control. So that song is kind of paying homage to the female energy. At least in my mind, I tried to broaden it into the aspect of matriarchal society. That, to me, represents that. That one was also been around for a while.

M.G.: But we hadn't played it in a long time. It went to sleep for at least five years. So it was kind of new. And with new members playing in the band, it’s also kind of new, only because it went to sleep for awhile.

A.A.: Gabe was kind of a catalyst for that song, and he wasn't playing with us anymore. We had some songs that we wouldn't play because one or two members who are actually primary composers of the songs weren't around anymore. They step down, and the song goes away.

M.G.: Well, not necessarily.

A.A.: Yeah, well, you know what I'm saying. Just happened to be the case with that song. It was not on our menu, on our set list. Some songs get retired.

B.E.: You end with one I remember from shows, "Sáré Kon Kon." That's a very strong song.

A.A.: That's also one of those songs that Gabe had written some words in English. We had been playing that song. I remember when he first wrote that, when that idea came, it was a very slow song. We played it at half the speed it is right now. We rehearsed it now and then and pumped it up to that speed. And that changed the flavor of it. Then, on tour, in the backseat, Gabe had some words. He wanted me to translate it into Yoruba, but it didn't quite work. So we argued it out. "This word would sound better, if you change the meaning it to be this...." So we kind of played around with words translated into Yoruba and it would sound a little better, a little harder. "Sáré Kon Kon" means "running fast" in Yoruba. But the way you say it in Yoruba, it sounds more like "can can." So this way sounds a little better, sounds more like playing bells. So we took the liberty to get a better sounding effect

M.G.: Like onomatopoeia.

A.A.: How's that?

B.E.: That's when things sound like what they mean.?

A.A.: Exactly. So that's one kind of approach.

B.E.: I read the recent New York Times piece about you guys, and it talks about how the environment has changed so much during these five years. Afrobeat is a lot better known now. In your experience, has the environment really changed so much in the five years that you guys been off-line?

M.G.: Yeah, I mean, it seems like everywhere we go, in every major city, there is at least one Afrobeat band.

B.E.: And that wasn't true five years ago, or less true.

M.G.: It was less true. It's been like a steady rise. I think that the music was seemingly so obscure to anyone other than serious music heads and crate diggers, but the music is infectious. It's undeniable. So it only makes sense that more and more people would become aware of it. And I think we've done a lot of work in promoting the music.

A.A.: Oh yeah. As a matter fact, my family used to tell me they didn't support this at all. They would say, "What you doing promoting someone else's music? You should play your own music." So my family never really totally wrapped their arms around me about Afrobeat. Of course, this is a family that would come around once it's successful. Like most families.

B.E.: That's your family in Nigeria?

A.A.: In Nigeria.

M.G.: But you know what I mean when I say the music is undeniable. The music has its own vocabulary. It has idioms. Once you get familiar with the language of it, then you can use it and make it your own. And that's what Amayo does with his music. That's what I do with my music. It's just flexible, and allows for a lot of innovation. It's just an expressive music. That's very general to say expressive. But the fact that it's so heavily polyrhythmic allows for a level of dynamism that you don't necessarily feel in like rock 'n roll, or just straight up funk music. It's very complex. So that adds to the DNA of the music. It allows for constant evolution of that sound.

B.E.: The other interesting idea and that article was the idea that it's such collective music. Even though all you guys are very accomplished musicians in various rights, it's really more about the mesh and the individual performances.

A.A.: Absolutely. It's the higher cause.

M.G.: Absolutely. To me that's one of the most beautiful things about Afrobeat music. You are a part of the greater whole. So your part is as important, and everyone relies on each other. It's a musical conversation that has to move forward, but only if people aren't talking over each other. It's an elegant to music in that way.

B.E.: And that's where the language comes in. There are rules that allow all those voices to come together and say one thing. You talk about using Afrobeat in merging with other things in your own projects. This new record is pretty straight-ahead Afrobeat. There's not a lot here that one would think of as really diverging from the formula. Talk about the tension between asserting the band's individuality and keeping within the rules of this language. How do you innovate within that structure?

A.A.: Well, it's almost like you pay your dues, you join the army, you go to boot camp, and then you develop certain a certain feel -- whatever you want to call it -- a second sense. Then you start understanding that there are certain parameters, certain set aspects about the music itself. The total conversation that occurs. The rhythms of it. There are just certain things that are right, and things that don't sound right.

M.G.: I would frame what you're saying as fluency. There's a certain fluency that we have in this music. So in order to be intelligible as a collective, we kind of agreed to a set of aesthetic parameters. And sometimes they're not necessarily always conscious. We know when it doesn't sound right. And we know when it sounds right. That's what Amayo is saying. And then sometimes the rules of the actual clavé dictate the rhythmic parameters of everything that happens, so if you start playing cross-clavé, it sounds wrong. And, again, that's just part of the language.

A.A.: It doesn't sit well. That's the thing. There's something about it that has to do with the body, and the way music affects the body. You hear a particular groove in Afrobeat... I mean, obviously there's something that you can just groove, but to have depth—that's where you get that, where you lose your mind on the dance floor. All of a sudden, you are transformed and you go to the other side.

M.G.: Yeah, because we're digging deep. The musical conversations were having with all the instruments are digging deep into the permutations of the clavé. That's what allows you to lose yourself in the music or on the dance floor -- whatever. These are like mathematical equations that our ancestors developed a long time ago for the specific purpose of having a communication beyond words that allows us to get through to that other thing, which really is a spiritual dimension.

B.E.: It's the idea that many voices, many impulses, many people are playing together, and organizing their ideas around that clavé. And you don't mean specifically the Cuban clavé, but it's that same idea as an organizing principle, the "key," literally, to all of the music.

M.G.: Right. It's the African clavé. It's a rhythmic structure. It's an algorithm really, depending on what clavé you're playing it will dictate what all the subsequent rhythms and the permutations of the clavé will allow.

B.E.: That's an important idea. A clavé is more than a rhythm.

M.G.: It's an architecture, yeah. It's kind of the skeleton that you can build everything around. And there's a few different skeleton models, if you will, that you can dress up however you like.

B.E.: Coming back to the CD, you decided to just call it Antibalas. The Times said it was almost as if you were reintroducing the band.

M.G.: I know there was a lot of conversation. I thought we were going to name it something else.

A.A.: Yeah, we had a couple of other ideas, I guess. But this got the best vote, because it just made more sense.

M.G.: Because we hadn't been out there for awhile, and it is kind of a reintroduction of the band, now that the profile of Afrobeat has been kind of raised through the musical, and it's much bigger than it was before.

B.E.: So you feel like you're starting a new chapter.

M.G.: It is definitely a new chapter. Same book. New chapter. Same old book!

A.A.: There was a time in the band when we all had to write why we were in Antibalas. We wrote our goals for ourselves and for the band. And one of the things that I wrote was that I would like the genre of Afrobeat to separate itself from "world music." Rather than just being under that umbrella, because the music has a high enough art within it to stand alone. And for that to happen, we had to have a whole culture around it, a movement. So you know what? I think some of my wishes are coming true. So this is the rebirth of what we started a while ago. Because when we started, we had no idea what we were doing or where we were going. We were just going.

B.E.: You know, in so many interviews I've done with so many artists, this comes up. Everyone wants to escape from the “world music” umbrella. But Afrobeat really has a shot at that. It is becoming a genre unto itself. People know what it is, more than a lot of other African music styles.

A.A.: Maybe it should be World Afrobeat.

B.E.: Speaking of that, there's one other thing I want to ask you about. This is kind of a paradox of your band. When you think about Fela creating Afrobeat, he's dealing with people from one cultural setting. He's the boss. It's a very hierarchical situation. But you are dealing with all these different ages, ethnicities, musical backgrounds, and there's no clear leader. It is a radically different model than the model that generated this music in the first place. And I would love to hear any reflections you guys have about the pluses and minuses of that.

M.G.: It's kind of poetic in a way. In many ways, I think it really shows how American a band we are. You know, when you think about it, we are a decentralized collective of musicians. I don't know if that could happen in Africa. Could that happen in Africa?

A.A.: No, it couldn't. No. It would never happen.

M.G.: LAUGHS. That's kind of cool.

B.E.: Well, that does sound fundamentally American. And that brings me to another question about something that most of you do share. The band is often described as a Brooklyn band. Is that important to you? That Brooklyn identity?

M.G.: Not to me personally. I mean, Brooklyn is cool. But I live in Jersey City, man.

A.A.: I think for me it's more like kinda just where it all started.

M.G.: Yeah, the inception of the band. I mean, back then, you guys all lived close to each other. Well, not all, but most of you.

A.A.: Yeah, most of us lived close. Just two or three blocks from each other. And then, our studio, before Daptone, it was called Soul Providers. So when Gabe moved his studio, he moved it to my basement. So that really made it like home. And Alex [the band's manager] lived on 3rd Avenue, in a loft. That was our headquarters to do business. So everything was centralized there. That was our address for a while.

M.G.: It probably couldn't have happened anywhere but Brooklyn, honestly.

A.A.: For that reason, it stays Brooklyn.

M.G.: When you think about it, it couldn't have happened anywhere else. Because I think when the band started, the rent was still cheap here.

B.E.: Right. That's over now. Try Detroit.

M.G.: The next great Afrobeat band might come out of Detroit.

B.E.: When you survey the scene of all these emerging Afrobeat bands, do you have any thoughts about it? You feel like they're generally promoting the genre well? Or do you feel like some of them are taking wrong turns?

M.G.: I mean, I'm not that familiar with the kind of Afrobeat that people are doing, so I can't really comment. But I would say this. The safest bet in terms of being able to play this music is to become fluent in the language, and the underlying structures of the music. And not gloss over them. Because without those things, it's like David Sedaris says in Me Talk Pretty One Day, you gonna get fluent before you can be eloquent.

A.A.: Yeah, you got a respect that form too. Either you are satisfied with it, or you want to do something else. Because sometimes in this American culture that we all try to either reject or, you know, this fast food mentality. We're like children. We are too quick. We want different things. We want the better and the best, and you never stop. So that process doesn't allow sometimes for want to really learn the language well, sit with it...

M.G.: Digest it.

A.A.: So a lot of times, we’re too quickly trying to find a different way of saying language. Like all the reviews we have been reading so far, and some of the reviews in Europe. They say things like, "The music sounds really great, but they haven't taken it to another level." And, I'm like, what do you mean, "another level"? What does that mean?

B.E.: That too seems like a very American, or maybe just Western, expectation, the idea that if you are going to play this music you have to change it somehow. It isn't enough to just play it well. But I like what you're saying about fluency too. Wasn't it Mozart who talked about freedom through discipline. You set the rules, and you live in a world where you really are free, because you've limited your options to a sensible set of possibilities. If you are all the options in the world, it's too easy to get lost.

M.G.: Totally. And that doesn't preclude the possibility of further innovation within the music. The fluency and the rules are what allow you to build upon what's already been done. That makes it part of the tradition. I mean, that's how I perceive what I do musically with Afrobeat. I see it as part of the tradition, and I'm not trying to stray from the tradition. I'm completely free to recontextualize and the poetic, and just innovate something that still is part of the tradition. I think that's important.

B.E.: Also, Afrobeat is such a hybrid form to begin with. It is a tradition, but it's a very modern tradition, and one forged out of so many different elements. It's hardly set in stone.

M.G.: No, it's completely fluid.

B.E.: So, last question. Where do you see all this going? What's this next chapter in the Antibalas book going to look like?

M.G.: Well, it is definitely going to involve a lot of touring.

A.A.: Yes.

M.G.: We've got a lot of touring ahead of us. But Luke and I have already started working on the next album. We all have started chipping away at ideas and stuff, but Luke and I have gotten together. He's the other guitar player. And, well, we kind of want it to be a little bit more guitar driven, the next album.

B.E.: As a guitarist, I can go along with that.

A.A.: More guitar...

M.G.: More guitars, man. Maybe fuzz him out a little bit. And of course, of course. There are always going to be the horns.

B.E.: I was going to ask you about guitar in Afrobeat. It's got a very distinctive role, but it's kind of a constrained one. In traditional Afrobeat.

A.A.: Yeah. If you listen to some of the later stuff, when Fela is starting to move forward with the music, guitars became freer. It's musical growth. As he is growing.

M.G.: African classical music. He was elaborating it more and more, and kind of following it to its next step as he saw it. It's what you were saying before, it's wide open. The way we are employing it, the guitars function as they do in Highlife. It's kind of like we’re playing rhythmic figures, and it kind of helps the little motor keep turning and turning, and moving and moving. I mean, there's something magical about that. You could see it as constrained. I see the music as an engine, with interlocking cogs. My part moves the other guitar part, which is moving with the bass line, which is moving with the drums... everything is interlocking. There is a freedom in that.

A.A.: There is language in that.

M.G.: Yeah, everything is saying something. It's one statement.

A.A.: And when that is happening, you start hearing voices. Then you know you're doing the right thing.

M.G.: That's what I'm saying. I don't see it as constrained because of that very reason. Because when everything is in sync, it starts revealing. It's like a mandala. Like when you meditate on a mandala. And I'm not trying to get too abstract about it. But when everything is in sync, it reveals something that you didn't necessarily expect. It unlocks something other than just what you are doing.

B.E.: That's cool, kind of like a percussion ensemble reconfigured as a band.

M.G.: Yeah.

B.E.: And that's true of a lot of the great African genres. You could say that about Congo music, or chimurenga music in Zimbabwe.

M.G.: Or you could say that about Cuban music.

Williamsburg Park, scene of Antibalas's 8-18-12 show.

B.E.: Sure, same thing. But each case is different, because it's always about the specific rules of that specific language. So it's going to be different every time. That's beautiful. Well I look forward to the new music. I look forward to the show tonight. Thanks a lot, you guys.

A.A.: Thank you. See you again.

B.E.: Count on it.