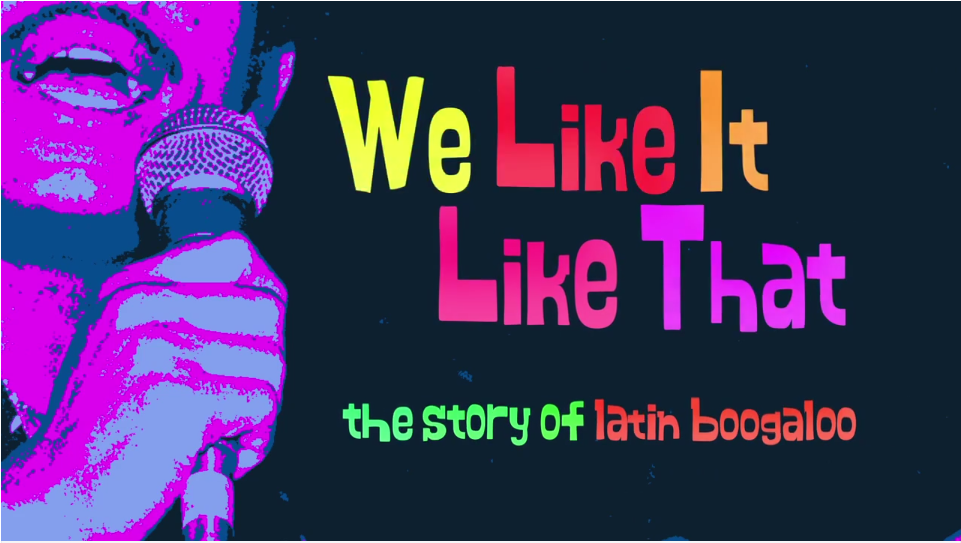

Mathew Ramirez Warren thought he just going to write a magazine piece about Johnny Colón, but now, five years later, he's heading to Texas to premiere his feature-length documentary at the South by Southwest music conference. Rather than just covering one of its stars in Colón, Ramirez Warren's documentary covers the life and all-too-early death of the genre known as boogaloo. It's titled We Like It Like That.

At 32, Ramirez Warren was too young to be around for boogaloo's first heyday in the mid-'60s, which fell between the end of the mambo era and the rise of salsa. Even in a simplified chronology of Latin music, boogaloo is sort of an anomaly—the lyrics are often in English, and the downbeat-accented rhythm sounds more like the r&b of the era than the mambo music many of boogaloo's key players cut their chops on.

Ramirez Warren told us how boogaloo was just one of those cultural fusions that happens in New York, where Latino and black cultures have mingled for decades. Its influence can be heard both in the salsa and disco that would replace boogaloo on the dance floor. In the course of our phone conversation, the filmmaker explained about how boogaloo is even echoed a decade later by the earliest hip-hop.

And of course, it's not like music this fun and exciting is going away, even 50 years later. DJ Turmix has a monthly engagement spinning boogaloo records in New York, and he was even willing to put together this fantastic mix of boogaloo hits.

If you can't make it to SXSW for the premiere, hopefully a well-soundtracked interview will tide you over until Ramirez Warren can bring the film to a theater near you.

Ben Richmond: What defines a boogaloo song? What defines the genre?

Mathew Ramirez Warren: If you ask the musicians, you'll get a lot of different answers, because everyone has their own opinion. But I can tell you what are common themes in boogaloo songs. We have a great example in the film from Orlando Marlin—a timbales player who is known as the Last Mambo King because he was very young when he started out during the tail-end of the mambo era, and had some success then, and who continued into the boogaloo era, and had some success playing boogaloo, too.

For the film, we were recording him in a studio space with the instruments in it, and so he demonstrated for us the difference between a mambo rhythm and a boogaloo rhythm. What you hear when he switches over to boogaloo rhythm is the downbeat, a kind of r&b-style downbeat, which we all know really well because of how much it was sampled in hip-hop music.

So it always strikes me when I watch that scene and I hear it. I'm like “wow, that's a hip-hop beat” but that's because I'm 32 and I grew up listening to hip-hop music. That's how I got interested in old records—same as other people into deejaying and collecting records—looking for samples.

I should say I am part Latino so I grew up with Latin music in my life. I've said this in other interviews, but it was something that I didn't think of as New York music, when I would hear Latin music. I would associate it with Colombia, which is where my mother is from, or someplace foreign. It was cool to discover that New York had played such a role in Latin music history. And that I really discovered from going to flea markets and record stores and getting to know the music that was out there and realizing that, wow, all this happened in the place where I grew up.

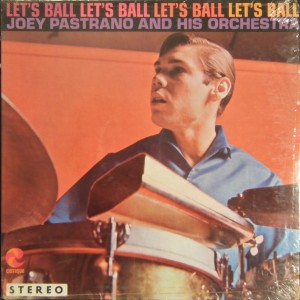

I was interested in trying to document what I could about this story, and I feel fortunate because there are two people whom we interviewed for the film who are sadly already no longer with us: Joey Pastrana, who passed away last year, and Jimmy Sabater, who passed away several years ago after we interviewed him. So it felt like the right time to do it, because that's the way time goes.

The '60s are now 50 years behind us, I guess.

From speaking to people who were growing up in the era, who maybe weren't musicians but who were still experiencing the culture, initially they kind of thought Latin music was sort of corny. It was their parents' music. It wasn't until they started hearing that fusion of what they had been hearing in the streets—from doo-wop, and as Motown was becoming more popular, and the whole r&b thing is getting big and it's what is cool and hip at the time.

The Latin musicians—who essentially were their peers because many of them were teenagers or very young when they started doing this sort of fusion between traditional Latin music with the soul and r&b thing—that's what got their attention; and that's what got them listening to both boogaloo and Latin music. Because these guys were playing their own renditions of more traditional Latin music, but adding a very New York hip sensibility to it. In a lot of ways that creates the audience for salsa—but I don't want to give away the whole movie.

So is this your first full-length documentary?

Yeah, this my first feature film. My background is actually more in journalism, so that's really what I was doing before I started working on this project. I was freelancing for New York Times, and then I went to NBC for a while, but what got me into this project was an article I wrote for Waxpoetics magazine. They were always one of my favorites, so when I got into the journalism game I was always trying to pitch them stories on any older musicians that I could dig up to get the story behind those cool rare records.

Did you come across a boogaloo record that you wanted to write about for Waxpoetics?

Well, I somehow was able to track down Johnny Colón and decided to pitch a piece on him, and that was my first entrance into the boogaloo world, starting down the road of what eventually became this film.

After meeting him, I started reaching out to other people; I thought it was just this really interesting story that hadn't really been told. The music was great, and I loved that it was this untold New York story. And as I dug deeper, I got more and more interested in trying to tell it and give it its justice and hear what all the musicians had to say about it.

Because it's a very unique period in Latin music history, as opposed to the mambo era or the salsa era. It was very important to New York and New York is central to both of those things. And a lot of people don't realize that, especially about salsa, about how it really actually synthesized in New York in the '70s.

Boogaloo is the period that comes right before this, and it just screamed New York because it was this weird mash-up of different sounds and different cultures. I was pretty fascinated by that. I like cultural hybridity and that's what New York is all about.

Out of those three genres—mambo, boogaloo and salsa—boogaloo has the most English lyrics, doesn't it?

Yeah, there were maybe a few mambos or songs from that period that had English lyrics. The Joe Cuba Sextet, which became famous in the boogaloo era, had started out in the mambo era and they were one of the first groups to do well with songs in English. And they ended up being one of the pioneers also in boogaloo, maybe because of that.

But yeah these were all New York guys; they were from New York. Most of them had come here as small children, and many of them were born and raised in New York. For many of them, English was their first language.

Among my friends who are into Latin music, most are vaguely familiar with boogaloo, or at least they recognize a song or two, but I never get the sense that boogaloo is widely known as a genre. Did you get a sense for how widely known boogaloo is outside of New York?

What I've come to discover is there are two groups of people who are fans: there are people who really grew up in that era, and who experienced it first hand. Generally these people are in the northeast, centered around New York. A lot of young Latinos, but also non-Latinos who were going out dancing and experiencing the culture. 'Cause it's New York; these guys are playing all over, down in the Village—it's not like these bands were only playing in Latino neighborhoods. It was part of the scene in the '60s. So a lot of people experienced the music and it resonated with them. It's been helpful along the way that people in positions to help have identified with it in that way. I felt very fortunate for that.

Then there's an international community of, for lack of better word, crate-diggers—people who are interested in deejaying or just collect old vinyl records. Scattered all about there are these people who are really interested in boogaloo, in Europe, in Japan, even in South America; this music is still pretty popular down there, even the English stuff has a following.

You also have to understand that most of the guys who became associated with the genre, if you listen to their records, they have maybe three songs that are considered “boogaloo” but the rest are more Afro-Cuban, salsa-leaning songs. So they were playing everything, but what they were doing was incorporating this new sound into their music, which I think that's had a lasting effect on Latin music, even into salsa, although salsa was leaning towards a more traditional Latin music. I think the effect of adding r&b rhythms and going further with jazz in someways.

I think of salsa as being the major heir to this music, but the “aaaahhh beep beep!” that you hear in Joe Cuba Sextet's "Bang! Bang!" can also be heard in a Donna Summer disco song. Do you see boogaloo's influence showing up elsewhere as well?

I think this era is an important predecessor for several New York music eras that follow in the '70s. Some, like Donna Summer, seem like a direct correlation, but for others it was less obvious, but what it represented is very similar. I see it as somewhat of a predecessor to early hip-hop in particular, because that was very much young Puerto Ricans and blacks getting together in the city to make music and stay out of trouble, and that's exactly what was happening with the boogaloo era.

And these guys were not the most trained or schooled musicians and so in that way it reminds me of punk too. They were breaking the mold! They were breaking the rules. They were simplifying the music to its core. There are people, to this day, who don't really like boogaloo. They'll say “it's out of tune; these guys aren't in clave," which is the golden rule of Latin music, a rhythm that all Latin music is supposed to fit into. But these guys didn't do that, you know? There are people to this day who will hear it and think it sounds like garbage, but there are other people who think that the imperfections are what make it so interesting. There's a lot of energy and enthusiasm in the music. It's not for everybody, but a lot of people identify with that, especially today.

Seems pretty clearly recognizable as fun music—and what's more, just like early hip-hop, it's also really funny. There's the part of “Bang! Bang!” where everyone's shouting “cornbread!”

And that's literally referencing soul food. It's people being like “we get down with this too.” There's someone in the film who talks about the exchange between Latinos and blacks in New York and she talks about the food: basically the black neighbors developed a taste for their cooking and they in turn developed a taste for soul food. So yeah it just reflects a cool cultural exchange, which was very prevalent in the '60s.

So, I mean, maybe Donna Summer heard “Bang! Bang!.” Some of the songs became big hits outside of New York, where the scene was mostly based. In the end the reason we named the film We Like It Like That is that I found as I was telling people about the project, they wouldn't recognize when I told them it was about boogaloo but they would recognize the song “I Like It Like That,” which was a hit as a cover in the '90s and was also a hit in the '60s as well, the original Pete Rodriguez version.

I kept telling people about that and eventually I realized We Like It Like That would be a good title, because it's about these people from different communities who created this fusion sound that they felt really represented them and helped them recognize themselves as a community.