Coreysan is happy in the pocket but won’t be put into a box. The bassist for Calypso Rose loves to lock in with the drummer and get people dancing for the Caribbean queen, but in between tours and dates, he’s a singer-songwriter, making music full of dark atmospherics, anchored, naturally, by a nimble low end.

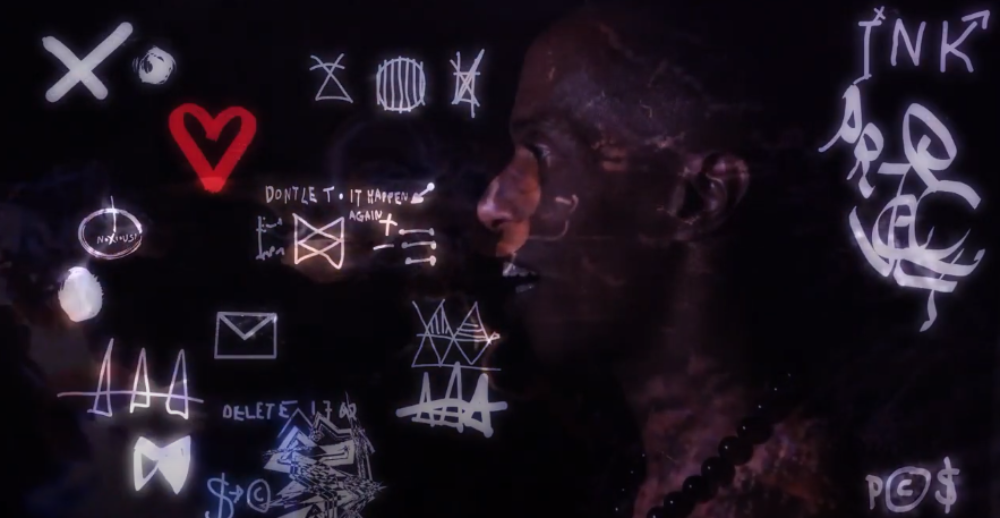

Based out of Bristol, England where punk music and that of Caribbean immigrants melds and incubates with visual arts, Coreysan has found a network of collaborators, including Ink Project, who features Coreysan’s face and voice in his new single, out today.

You can hear the tendrils of Bristol’s past—the dub grooves and atmospheric, glitchy electronics that characterized trip-hop—on Ink Project, as well as Coreysan’s own music.

Afropop’s Ben Richmond contacted Coreysan, who was still sheltering in Paris, via WhatsApp last month to talk about the new single, Coreysan’s upcoming solo album, Deeper Than Skin (out on Oct. 30), and what he’s learned from holding down the rhythm section for the one and only Calypso Rose.

We should introduce you to the Afropop audience who doesn’t know you—do you want to introduce yourself?

OK, I am Coreysan. I’m a bassist singer-songwriter. I produce electronic live music, I call it “Caribbean hybrid music.” I’ve been doing this for 33 years of my life. I was born and raised in Trinidad and Tobago, based out of Bristol, kind of between Bristol and France for most of my musical career, for the past 12 years.

Is Calypso Rose based in France now?

She is huge in France now; she is a queen. She’s the queen of France. The last three, four years, it really really took off, because she did an album with Manu Chao and I think it reached a larger audience and everything went up a level.

Is she big in the Caribbean diaspora there in France or is she catching on across France?

It’s more people from France and whichever other parts of Europe that come to these shows. You may see one flag from Trinidad, two Trinidad flags waving along, but the popularity is not just within the Caribbean. She’s really kicked the door open, to be honest, at 80 years old, which is incredible.

She is irrepressible! And you play bass for her?

Bass and backing vocals.

I’m always curious, someone who has their own project and another gig playing with someone, what do you learn from touring with Calypso Rose?

For me, basically I’m playing with my history, there’s a little bit of history book. I grew up here as a child and she’s the only queen of Calypso music. So that in itself blows my mind. This is the closest I’ve gotten to playing calypso music, because coming from Trinidad everyone knows and hears calypso but the bands that are performing are all performing hybrids. She’s doing her own hybrid form, but it’s closer to the traditional thing. But, the thing for me, I like both worlds. Doing a project by yourself is nice. You get to escape all the drama of finding a drummer and the keyboardist and somebody has to pick up their girlfriend so he can’t come anymore and...But I do love and can’t get away from the aspect of playing live and playing with people. You know, I get to experience difference. It gives your mind a reset and gives you a new perspective on your project. It helps you stay fresh.

Yeah, and you’re keeping your chops ready. Although on the Coreysan music I’ve been listening to, I think of it as more electronic based. Do you still play bass on those recordings?

Oh yeah, all live bass on those recordings.

Before we get into those, you’re now based in Bristol and Bristol is famous for its Caribbean diaspora. But how do you find the music scene there?

Well, I would say, obviously, Bristol because it’s just a really innovative city, with Massive Attack and Tricky, that was a big influence for me. I think it allowed me to spread my wings a bit because I guess in my growing up in Trinidad, even though there’s a culture of being innovative and mixing genres and stuff, I guess we still have a big influence from America, so things have to sit in boxes. So things have to be like, if you’re doing reggae you have to sing like a Jamaican, if you’re doing gospel you’re singing like somebody from the United States, if you’re doing soca, it’s becoming more influenced by pop. And I think even though I was just stubbornly doing my thing regardless of what’s going on around, I think being in Bristol, they don’t require you to fit in a box. Just has to be real, just has to be honest and has to be good, you know? Of course, I have to put good there, because it can’t just be real, honest and all over the place. I found myself not having to explain. Sometimes when I’d play for Trinidadian audiences, they’d look at me blank and I’ve have to give a little introduction, but in Bristol, people are like “no, you don’t have to say anything. We get it.” So that was one of the most refreshing things about being in Bristol; I feel like my creative wings got a little more room to spread.

That’s interesting. Especially, when you’re working solo, do you get feedback from friends in the scene as you’re working or do you keep it close to the vest?

No, I play a lot of solo gigs in Bristol and the bands I’ve played with in Bristol are because I might have opened for them as a solo artist. There’s a mixture of people in the scene who give me good reviews but it’s more the ear of the scene than the players. The players need listeners and the listeners have a really diverse taste or...diet.

I guess that segues nicely into your busy fall. Things are calm now, but the Ink Project is coming out. You’ve lent your voice and face to the Ink Project—do you do any production also? Any bass?

Most times we just do me and the music and I think it’s full or rich enough. But I’d play bass on some of the songs live, just to give the songs an extra bit of spice, you know? But at times, Jez [Lloyd, the man behind Ink Project] would come up with the music, maybe give me a title and maybe I ask him what he was thinking when he wrote. So just with the title I wrote the lyrics and recorded the song and sent it to him. And we’ve been working like that for...three years now? This is the second album I worked on with him.

Is he someone you met in Bristol?

It’s funny, one time I did a solo album when I moved to Bristol. Tricky, I like his music a lot, and Tricky had put out an album and it featured a song called “If I Never Knew” by an artist called Fifi Rong. She is Chinese but based in London, and I really fell in love with the track and I decided to check out her Facebook. I’m glad I took the chance, but I don’t really remember what I said. I just sent a message, and said “I really love your music, da-da-da-da, I’m a musician too. I just finished an album; I’d love for you to have a listen. Let me know what you think.”

I just took a chance and she liked it. She was already working with Jez from Ink Project, because she worked on his first album and Jez was looking for, as she described it, Jez was looking for somebody with “Caribbean flavor but not too preachy, and not too religious, and not too ‘oh you must do this, you must do that’ just somebody who can write nice songs.” And she said, “I have the man for you.” Literally like that, magical like that.

Even telling you now it’s a bit...man—if I did not take that chance that would never have happened. So after Fifi and I connected, she connected Jez and I together. And she’s on this album too, she’s on the second album of Ink Project, one of the collaborators on the session.

I liked the Ink Project—very atmospheric, very far afield from Calypso Rose.

I hope so—I mean that’s the weird thing, I do this, I do that one, I do a collaboration with a reggae label, I’ve played on electronic labels—music is music and I’m a musician, not a type of musician. I don’t really stay in a box where I’m from Trinidad so I should play calypso. When someone says “should” I’m already walking away. I’m a born musical dissenter.

Even though it’s producer-based music, you describe your music as live. What changes when you’re going up alone? Do you have a band or do you bring up visuals?

For now, most times, for example, for Ink Project sets we mix it half in project, half Coreysan. So Jez will do all the samples and running the beats and stuff and I would sing and play bass. But when I’m doing my stuff solo it’s really just me, a laptop and my voice. In my past, I had the theremin but the theremin is too troublesome for me to travel with—Soundcheck can go okay, but if the guy in the front row has too much to drink and starts wavering it affects my pitch! But that’s temporary. I told Jez, if we play a bigger place where I’m not going to be affected by proximity, then it makes sense. Other than that? Rock & roll laptop, bass and voice. The theremin was an added aspect, but the bass and voice was the main thing for me. I’ve been playing bass since age 16. Theremin only came in when I went to a Millennial Music Conference in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania and I met—as I describe it—Obi Wan Kenobi, and he made me a therminist. I had no intention, but now, he made me a thermin player.

The theremin chooses you, really.

It’s weird. Rico was his name and, I mean, he looks the part too. He has a white beard and everything. He was there in Harrisburg giving a rundown and at that conference I was the only person performing with a laptop, and it seemed strange to everybody then, but this was 2008, 2009 somewhere around there. Everyone else was full-on instrumentals. And Rico was like, well, if you’re into the electronic thing, come by my booth, I have something to show you. And I think he freaked out because he noticed that I did not just go for crazy sounds, I started to play notes immediately. And I watched a documentary about theremin right before that conference, but I didn’t have any want or question the universe “Oh I’d like a theremin.” It just happened.

You were ready for it, but didn’t even realize you were primed.

Master Obi Wan saw it better than I did.

Yeah, that transitions nicely into talking about Deeper Than Skin, the album that’s coming out this fall.

Yes that’s my fifth solo album.

Listening to it reminded me of some U.K. stuff, not just Bristol, but the Manchester, Hacienda sound. Maybe it’s that you compose with so much low-end and baritone voice.

I feel you. Some people always say there’s some David Bowie and The Cure in there. Those are big influences; I love The Cure.

I could hear that, especially on those later Bowie albums when his voice gets a little deeper.

From Let’s Dance onward for me.

But who are some other influences on Deeper Than Skin?

One of my biggest influences, and why I’m doing the project as a bassist frontman is Jah Wobble. Jah Wobble is a bassist, he was around that whole Sex Pistols scene and he and Johnny Rotten were part of Public Image Ltd for a little spell. But he’s a bassist that fuses everything—North African, Eastern European, Indian, Chinese, but his bass is almost mostly Caribbean: reggae and dub—fat, sensual bass. That really was a big influence on me.

I love fusing and coming from island that’s all fusing, hybrid people. Fusion is a natural thing for me to do coming from Trinidad, which is historically all fusions in our culture. So when I first heard him I was like “Man! He sounds like he could be my next door neighbor!” So close to home! And “wow, you can do this? OK!” And there’s the whole, yes live instrumentation, and there’s an electronic part. You can check out his Rising Above the Bedlam by Jah Wobble and the Raiders of the Heart, I think you’ll get it.

That era of music—when punk comes into its own, with The Clash and Public Image Ltd being big fans of Caribbean music.

And The Specials! That era of U.K. music, there is Caribbean music very present all over British music. That bass element—a lot of good bass players have come from the Caribbean but in England they’ve really perfected that whole bass culture, sonic thing, you think? Especially in Bristol, with drum and bass and dubstep and speakers rumbling, the drinks are dancing on the bar because the bass is making the bar move. I guess that kind of resonates with my whole experience of going to reggae dances and stuff in Trinidad, where the bass is a physical thing—it’s not something you listen to; it’s something you feel. You have to hear it in its space, and you have to feel the bass.

Do you think that’s what first attracted you to the bass as an instrument?

Yeah, yeah, I mean that question is always a weird question. I can kind of vaguely remember when I was younger I would draw bands. I always wanted to make music when I entered secondary school, and started on guitar but I was still always figuring out bass lines on the last four strings. Then barre chords came in and I was like “nope! I’m not learning that.” I’m playing bass. The school band needed a bassist, so I played bass. I could see that from age 16 I committed myself to learning the bass.

Did you ever supplement that with learning the drums at all?

Well, you know, that’s a really good question because bassists like to fiddle with drums and drummers like to fiddle with bass because, you know, it’s husband and wife. It’s a team. So I guess my experience with drums comes from the program Fruity Loops, where I could actually make the drum beats.

And I love playing with drummers, really good drummers. Calypso Rose has an excellent drummer, and I’ve grown so much playing with him. Like I tell friends, when you have a nice drum-and-bass team and our motive is to stay back and make the people dance. Yeah, you have your star up front and whatever but once we see the bodies start to move....we don’t budge. And it’s almost like a weird kind of vacuum up there around us and we’re in our own world, doing the sequence but just, it’s a physical thing. Drums were used as a form of communication and stuff, so it’s not just aural, it can evoke things in your being. So I never officially learned the drums but you know, at soundcheck when the drummer is working on something else, you sneak in a fill.

And also, if you’re making music as a solo artist, you’re going to get a lot of practice with it.

Exactly. Yes, my music is electronic, but I still program the drums like a drummer. I feel what the drummer does, and I program drums as a drummer would play.

You know, I’m a professional amateur—the word amateur comes from amor, someone who does it from love. Yes, I’m doing it as a profession, and I love doing it as a profession. And if I had to take work as a gardener, I’d still be doing music, and I’d still be a musician. Musicians play! That’s the end of it. Before I had access to Fruity Loops and Reason, before I even owned a four-track I was doing the two cassette players thing, recording on one tape, and then playing back what I recorded and recording over the top of that, like eight times. At the end of it, you’re just happy to hear your song, even though you’re hearing about 20 snakes hissing on the tape—you don’t care! That’s the whole pleasure: “Wow, I got it out of my head!” And when the whole electronic thing kicked off, it’s like “man, I can get everything clean! I don’t have to wait on musicians or dream about making money to rent the time in the studio, I can just make music.” That’s what it’s about! Just making music.

And you can finally choose your atmosphere instead of getting forced into collaboration….

Exactly! No snakes!

Or, exactly as many snakes as you want.

Right, now you choose cobra or python, and you can put cobras on the bass and rattlesnakes on the high hat…[laughs].

Soca has a producer element, but people talk about atmospherics, I think they’re usually talking about electronics, but there’s an atmospheric element, especially in the rhythm section of soca isn’t there?

Of course! That is an atmosphere. Different parts will give it different feelings. You’re right that every time people talk about atmospherics they mean keyboards like Dead Can Dance, you know, ethereal-sounding things, but the drums is an atmosphere. Think of batucada--same drums, same scale but a totally different atmosphere. Yes, drums do play a big part—of course with the African influence in the Caribbean, drums have a big role in the music we produce.

As a musician you think about the effect music will have, but as you write and record do you think about where and when people listen to the music you’re making? This is “late night music” or “early morning track”?

Not really, no. I don’t know if it’s a good or bad thing. I don’t believe in music just being for musicians. I find that very limiting. I mean everyone has their own rules, and I don’t want to diss anyone’s rules. There are musicians who make music for musicians, but I want to play for people. So I’m still always trying to create ways to reach out with it.