Naresh Fernandes is one of the experts we spoke for for our recent Hip Deep episode "African Sounds of the Indian Subcontinent." He’s a journalist and author, and writer of the book Taj Mahal Foxtrot – the definitive history of Bombay’s jazz age from the 1930s-1960s. In his words the book is about “listening to the city through the ears of its jazz fans and its jazz musicians.”

The book, illustrated with stunning sepia pictures of Bombay’s historic locales and dance bands, draws readers into the fascinating world of the African American jazzmen who found themselves living and working in Bombay in the early 20th century. But Naresh argues that India’s jazz age is not just a oddball footnote to Indian music history – it was fundamental to the creation of Hindi film music (a.k.a Bollywood music), India’s great pop music tradition, and a multi billion dollar export industry today.

Below, read a transcript of our full interview with Naresh Fernandes. Listen to him on our show here, and learn more on Naresh’s fantastic web site for Taj Mahal Foxtrot, which is constantly being updated with new tunes and stories of India’s jazz age.

Marlon Bishop: How did you become interested in the story of Bombay’s jazz scene to begin with?

Naresh Fernandes: You know it happened because I like to gossip with old men. And I was talking to the father of a friend who lived down the street from me, named Frank Fernand. He told me about how he came to Bombay in the 30s from the Portuguese colony of Goa to play in Bombay's famous jazz bands, and how he and his peers at that time were completely taken by this new sound that was sweeping through the world, a sound called jazz. Bombay in the 1930s was filled with African American musicians who were playing at Bombay's big luxury hotel, the Taj Mahal. And every boy from Goa who came to Bombay wanting to be a musician dreamt of playing alongside these legends.

As I began to talk to Frank Fernand, I realized that not only had he lived through an astonishing period of learning to play jazz from African American masters, but that a few years later, he and his friends would take the same spirit of improvisation and swing into the Hindi film studios. And they would create a whole sub-genre of Hindi film music, the most popular music India has ever known - a real sort of jazz-based, swing-based vernacular form of pop, that continues to persist in the subcontinent.

M.B.: So help us set the scene - what was Bombay like in the 1930s

N.F.: In the 1930s, India’s freedom struggle against the British had reached a crucial stage. The effects of the Great Depression were just being rolled away and by the mid-1930s, Bombay was coming into its own as a confident global port city. Across Bombay, buildings were rising again in the art deco style, with Indian characteristics. And alongside this, was also a great sense of political freedom, which was being transmitted into the arts. There was the first burst of Indian writing in English, both in poetry and in the novel. And this is the backdrop against which jazz then became very popular.

M.B.: Much of your book takes place in a luxury hotel called the Taj Mahal. What was it?

N.F.: Well the Taj Mahal was a strange thing in that it was where Bombay's richest people gathered, and yet it became the node of essential transmission of cultural messages between East and West. Luxury hotels in Asia have always been this place where local elites got their first taste of the latest fashions and cultural trends from around the world, and also where local culture was served up in a sort of palatable form to visitors from other places. So even though these were spaces where very affluent people met, they were also the places where some experiments were happening.

In Shanghai, for instance, the jazz that was being played in some of these luxury hotels later became some of the most significant influences on Chinese pop music. In Cairo, people like Umm Kulthum, the great Egyptian singer, would see for the first time these big ensembles and make an Egyptian pop out of that. The same thing happened in Bombay.

“Chattanooga Choo Choo,” The Taj Mahal Hotel Dance Orchestra

M.B.: When does jazz first arrive in India?

N.F.: Jazz, in a storied way, arrived in India in the winter of 1935, when a violinist from Minnesota named Leon Abbey brought the first 8-piece band to Bombay. And Bombay society was all agog! This was finally the chance to foxtrot to this music that was capturing in the imagination of their peers around the world. And yet when Leon Abbey came to Bombay for the first time, this upper crust elite was sort of slightly thrown into disarray because Leon Abbey's quickstep was so quick for them, they could barely keep up with his rhythms!

And an old musician who is now in his 90s who sort of looked over this told me they came to hear Leon Abbey and begged him to slow it down a little and Leon Abbey did slow it down for a little while and then took the rhythms up again and this musician told me Leon Abbey chuckled and said, "First they swore at my music, then they swore by my music."

And that is how sort of swing first came to Bombay. But Bombay is a port city with a long tradition of listening to Western music of all sorts and so, strangely, in the 1860s, Bombay was also part of a circuit that brought minstrelsy music to India. So there were all sorts of white people dressed in blackface performing caricatures of African American life for audiences of brown people.

“Stampede,” by Leon Abbey and his Music Makers

M.B.: Wow – it seems so strange to me that Indians would be interested in minstrelsy, which was a form so specific to United States’ society.

N.F.: Well, minstrelsy music, in its time, was among the early forms of global pop. And so these minstrelsy companies were making their way all the way from London to the Gold Coast of Australia. And India and Bombay had always had a taste for whatever was happening around the world, and Bombay wasn't going to be left out.

M.B.: So back to jazz - of all places, why did these African-American jazz musicians end up in Bombay?

N.F.: There was actually a big circuit that was set up between Paris, Bombay and Shanghai. And after the end of the first World War, several African American musicians made their way to Paris and set up a whole bunch of Harlem-style cafes in Montmartre. In the 1930s, France passed what was called the “10 percent rule”: that only 10 percent of orchestras could be foreign born. When this took effect, the community of ‘Harlem in Montmartre’ was sort of thrown into disarray, and many of those musicians then had to seek other job opportunities. Some of them went off to Shanghai, which by 1935 had more African American musicians than Paris had. And some of them dropped off in the middle between Bombay and Calcutta. And they continued to travel the circuit some of them between Shanghai and Bombay.

M.B.: What was life in Bombay like for these musicians?

N.F.: By the 1930s Bombay had probably two dozen African Americans living here, in various formulations, coming and going, mainly centered around the Taj, but also playing in a couple of sort of country clubs where the elite congregated. To many of these African American musicians they were escaping racism at home and they were treated magnificently in Bombay. Dishes were named after them at the Taj Mahal. When Teddy Weatherford, who was a stride pianist who spent many years in India was asked why he chose to live in Bombay, he said, 'Ah, that's because they treat us white folks fine here.'

M.B.: So there wasn’t any racism in India? I understand that in Hindu society, caste correlates somewhat to skin color.

N.F.: You know in a strange way Indians are very racist, ]but the African Americans seemed to transcend that sort of discrimination I think because they were American: they sort of cut a style and had a glamour about them. And also - because they were playing in sort of elite spaces And so I think rather like they managed to transcend the racism in France, they also transcended racism in India.

M.B.: Your book, Taj Mahal Foxtrot is named after a jazz song that was played at the Taj Mahal. What’s the story behind that song?

India doesn't have a sound archive so the tracks I put together were essentially rescued from various flea markets and cleaned up, so they're very scratchy and they bear the mark of the passage of the years, that's for sure. I really delighted in that song when I found it because I thought that it really brought together a story of Bombay. It is a song that's performed by Crickett Smith and his Symphonians, a bunch of African American musicians, mainly, but also with a guy from Martinique and perhaps a musician from the Philippines, which really spoke to the internationalism of jazz in Bombay in the mid-1930s. But it was composed by a guy named Mena Silas, a composer from Bombay, who was actually a Jewish man whose family had lived in Bombay for many generations. I love the fact that the first real ‘hot song’ that I've been able to trace, was performed by African Americans but composed by an Indian.

“Taj Mahal Foxtrot,” Crickett Smith and His Symphonians

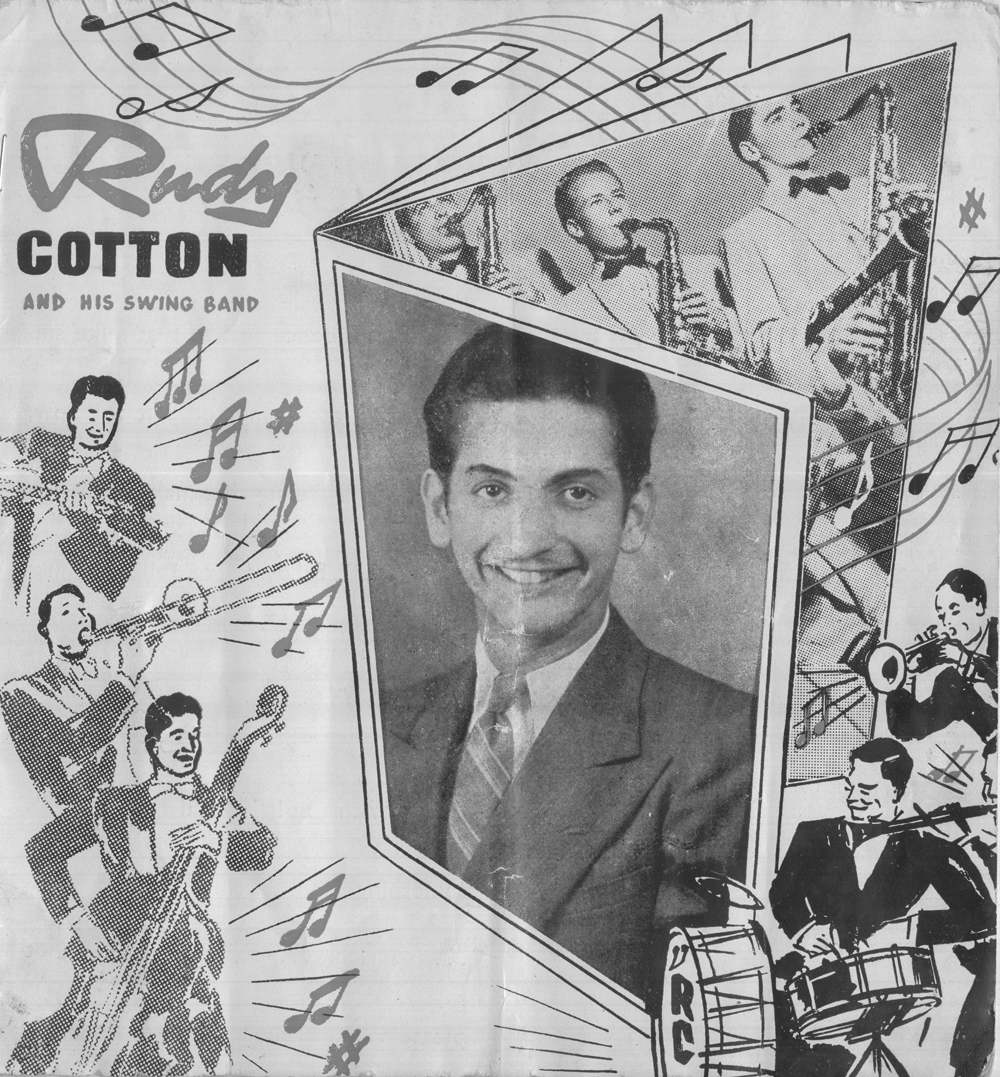

Cricket Smith and his Symphonians

M.B.: So, tell me about Indian jazz musicians who arose during this time.

N.F.: Well, among the characters who completely fascinated me was the man who set me off on this quest, Frank Fernand. He had a keen ear for the changes in the global music world but was also deeply interested in what was happening in India. In the 1940s, when he was playing at a resort in Mussoorie, Gandhi happened to be passing through. Gandhi gave discourses and lectures everyday. Frank Fernand listened to one of them, and it completely changed his life. He went away trying to find a way to play jazz in an Indian way. And he succeeded, or, at least we think he succeeded because there are no scores or recordings of what he did, but we know that by the late 1940s, he is listed in concert notes as playing jazz with an Indian theme.

And so long before people like John Coltrane were introducing Indian elements into jazz, Indian jazz musicians were trying to find a way to root jazz into their context, to say that jazz was a global language that could be spoken in many different ways. And while Frank Fernand was doing that on the concert stage, he and his friends were trying to find a way to play Hindi film music, the greatest pop music India had ever known, and to introduce jazz elements into that

M.B.: How did jazz end up having an impact on Hindi film music?

N.F.: I think that jazz and Hindi film music really became the sound of this new India. We had a notion of ‘Unity in Diversity,’ which was the phrase of the first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and this was really sort of reflected in the way Hindi film music got created in the studios every day. A lot of the melodies were crafted by men who were Hindu, with training in the Hindustani classical tradition. But their best lyrics were crafted by Urdu-speaking Muslims. And in order, then, for this to be performed by orchestras, the arrangers were jazz musicians from the Portuguese colony of Goa.

And every day these guys would sit together in the studios. Often they didn't even have much to do with each other in real life. But in the studios they found a way to bring their strengths together and create this sort of music that then all Indians then grew to love. So this was, in the Hindi film studios every day, a vision of Nehru's India being created.

M.B: Why Goa?

N.F.: Hindustani classical music is melodic - everybody reiterates a single line. But in order for film music to be truly effective, you need to have these large orchestras with harmonic instruments – trumpets and violins. The Hindustani musicians who composed these melodies didn't know how to do that. As it happened, the only people in India who did know how to do that at that time were these Goan, Roman Catholic musicians who learned how to play harmonic instruments in parochial schools that had been set up by the Portuguese, almost from the 16th century.

It would be the role of the arranger, the Goan arranger, to take down little fragments of melody and he would then go back to the studio and craft it. And, as he scored it out, he would throw in his own experiences of Ellington doodles that he picked up in the dance bands, and other things he'd listen to.

Also the only musicians that knew how to play these harmonic instruments were also Goans. Many of them had had experience in the dance bands or in the Western classical orchestras of Bombay. And so it was this great coming together of people with dance band experience Hindi film music this sort of really swinging sound.

“Eena Meena Dika,” from the film Aasha (1957)

M.B.: Aside from music, have you drawn any other connections between African-Americans and Indians? Were there other ways in which African-Americans influenced life on the subcontinent?

N.F.: African-Americans have had an enormously huge impact on Indian cultural and political life at the time, even if we don't quite realize it. There was this idea of freedom, the idea that as African-Americans were struggling against segregation and Jim Crow laws, and India was going through the same thing. And America proved to be very important refuge for many Indian freedom fighters all the way from the 20's, they were having conversations with African American leaders, some of them lived there for many years.

Even after independence, as Indians sort of won freedom from the British, there was still the Civil Rights movement that was continuing in America. And this continued to really inspire the dalits - lower caste Indians. In Bombay in the late 1960s we saw the formation of something called the Dalit Panther Party - a party of young radical lower caste people, directly inspired by the Black Panther Movement. So this continued for generations.

M.B.: Of course, Gandhi ended up being a major influence for Martin Luther King Jr.

N.F.: Yes, and Gandhi had spent the first 33 years of his life in South Africa, sort of honing his techniques of passive resistance and these kind of things. And by the time he came back to India, African-Americans were already looking to Gandhi to see how his struggles could be used to overcome segregation in the American south. And so the year that Leon Abbey came and was playing in Bombay was the year that the first African-American delegation led by Howard Thurman, who was a pastor and civil rights leader, came to India to meet Gandhi.

There was an intriguing moment one evening in that winter of 1935 when as Leon Abbey was playing up the road at the Taj, just 100 meters away, Howard Thurman was speaking to Indians at the university, giving a lecture on the African American freedom struggle. Howard Thurman and his delegation later went to meet Gandhi and the meeting ended with Gandhi asking them to sing negro spirituals and so that's what they did, they ended up that evening singing “Climbing Jacob's Ladder” and these other songs from the American South in the middle of West India. I've always wondered what that moment sounded like.

Transcription by Jocelyn Bonadio.