On October 4, 2012, shortly before the release of K'naan's third album, Country, God or the Girl (A&M/Octone). Afropop's Banning Eyre sat down with the artist for a chat. K'naan is an unusual African musician who inhabits an uncertain zone between hip hop, folk, rock and African pop. No surprise, that can be uncomfortable. For Eyre, it's the mark of an important voice in today's popular music. Here's their conversation. Also check out Eyre's review of K'naan's recent concert at New York's Highline Ballroom.

B.E.: The last time we met, Troubadour was just coming out, and you told me the story of how you wrote the song "Waving Flag" working with Bob Marley's sons in Tuff Gong Studio in Jamaica. It was obvious to me then that the song meant a lot to you personally, but it was far from obvious that it was going to go to number one in 18 countries?

K'naan: No.

B.E.: So what has that song done for you? How has it changed your life to have that amazing success?

K'naan: Well, I've got to say it is such a strange and puzzling world. It still is today. The idea of a success. The idea of the song's success that just kind of finds wings and flies off and invites you to different places where it lands. You are just kind of following it around for a bit. You know? "You're my child. I don't know how to do this that you are taking me around." But it's got its own amazing gifts about it, to have that kind of song recognition and all of that. But it's something you have to be careful with also, because it can become its own thing, its own animal. It's kind of a beast of its own. It's very extreme to experience that, being an artist who writes a lot of different kind of stuff.

B.E.: It has been remarkable to watch what happened with that song. But now, you come back to the studio to make a new album. What was the concept for this album going in? And along the way, explain to me the title.

K'naan: Actually, funny you say that. Because the title came along the way too. The concept of the record kind of found its own voice somewhere in the middle of making the record. I don't know if every other artist does this, but I have this habit of, whenever I start a record, I almost start it three different times in the same process. And it will be very different visions and very different vibes and feelings, and then, somewhere, I know what the record is going to be. And Country, God or the Girl came out of a conversation. Another artist friend asked me a question, which was, "Is this about that girl--you know, these songs?"

And I said, "Well, not all of them are about that girl. And even the ones that are, you couldn't tell if it was about country, God or the girl." That's how that came about.

B.E.: I get that. Thinking about these songs, that makes a lot of sense. What about on a stylistic level, as a musical statement? Did you have any particular goal here, or were you just writing a set of songs and letting each one take you where it took you?

K'naan: I was doing that. For certain songs that belong together, I wrote them back to back, and they feel like that. Like "Gold in Timbuktu" is a cousin of "Waiting is a Drug," that is a cousin of "More Beautiful than Silence." And this Dylan cover that I rewrote, which didn't get on the record, and came out in another way...

B.E.: Which was the song?

K'naan: "God on Our Side." And that was born at the same time as "Gold in Timbuktu," and if you listen to those four songs together, you get a sense of that time was like, when I was writing then. And it's very different than other songs on the record. So it's just different times in different feelings that makes the songs have different vibes about them.

B.E.: Let's talk a little bit about "Gold in Timbuktu." You probably wrote this before Timbuktu came into the news this year.

B.E.: Let's talk a little bit about "Gold in Timbuktu." You probably wrote this before Timbuktu came into the news this year.

K'naan: Yeah. Before the problem.

B.E.: It's an older person reflecting on youth. You seem kind of young to be having that perspective? Are you imagining this?

K'naan: Yeah. I was putting myself in that place. Being older. It's hard to see that. A young person, or younger person, has a hard time imagining old age. And I wanted to see if I can see myself that way, in the middle of the song, if I could spot myself that way. But also it's a conversation with my son, my little boy. It seems pretty sad to talk about your child in that way of like, do I envy my child for their strength and youth and age? But it is human. It's a human thought to see yourself in a young person doing the things you can't do anymore.

B.E.: The older you get the more you think about that.

K'naan: A lot of my artist friends connect to that song deeply. The song came out yesterday. I put it out on the Internet. And I was saying on Twitter, the amount of artists that it means so much to is insane. I got an e-mail after having heard it from Jay-Z, who said, "I want to thank you for this song, because it made me stop whatever I was doing and call my grandmother."

B.E.: That's beautiful. He must've been on his day off from the Barclays Center, his home away from home this week. But I get that. It's a beautiful song. Let me ask you about the children's voices in the opening song on the album, "The Seed."

K'naan: Oh yeah. They are Motesart's kids, the guy who plays the piano and guitar on that song, very talented guy. He's from here, New York. I wanted to get like a bunch of kids to sing that part, but then he got his two nieces I think to do it. And that was all that it needed to be. The underwhelming choir of two kids' souls.

B.E.: That's just two kids? No overdubbing?

K'naan: It might not be much more than that, actually.

B.E.: It creates the impression of a larger group. I imagined you were in a refugee camp talking to kids, because of the refugee theme in the song. It creates the illusion.

K'naan: Which is good. I thought a lot about that. That song is about Dadaab, in Kenya, the largest refugee camp in Africa. I had visited Dadaab, and so that was definitely what I wanted to send out.

B.E.: It's a rockin' song. We talked in an earlier interview about the Ethiopian samples on Troubadour, and you made reference to an East African sense of melody. Something you grew up with. I notice that your melodies are very distinctive. A lot of the time, they are forthright, on the beat, anthemic, march-like. That's a quality I pick up on. But if you were to try and describe that sense of melody that comes from your own background and upbringing, what would you say about it?

K'naan: I think I grew up on propaganda songs from the government. And actually that’s just occurring to me now. I had never given that thought of why it feels on-the-one and anthemic and march-like, melodies that I always have… Even "Waving Flag" is that. Because I just realized that all throughout the 80s and early 90s, the dictator Siad Barre ruled the country, but he used to commission these large bands that had like 20 singers, almost like military bands. That was the culture then. You had ten women and ten men, and they would sing together. And he used to commission them to write songs about the country, and about unity and about production and about good will for the other and that kind of thing. SINGS. And I think that might really have affected the way I see melody.

B.E.: That's interesting, that sort of forthright, declarative quality.

K'naan: Yes, exactly. "Let’s go. Let’s do this." And it doesn’t matter if the front line falls. But we are here. We’re going to keep going. This kind of charged vibe I think comes from that.

B.E.: It works really well with the strong refrains that you have, and it also easily moves into rap. Propaganda is good for something I guess.

K'naan: Yeah. I hadn't thought of that, actually. It's really good to realize that.

B.E.: Well, I was struck by that thing you said about an East African sense of melody. Are there other things that you think of in your musicality that come from your African background? We talked about Troubadour, which was very concerned with telling your story as an African and juxtaposing that with hip-hop narratives. But this record seems more like a universal pop record, and to my ear quite a brilliant one.

K'naan: Thank you.

B.E.: But are there other things you would point to that come out of your African experience?

K'naan: Probably perspective. Just the way that I write, it comes from a different experience. It comes from an angle of life that not everybody music today is standing on. So that's why the constant juxtaposition of something painful into something triumphant is always happening in the songs. The constant feeling of folk traditions is also happening in the songs. Because it's just that I stand in a different place. Not to overstate a sense of uniqueness, but really just a sense of history. I stand in a different place because of that.

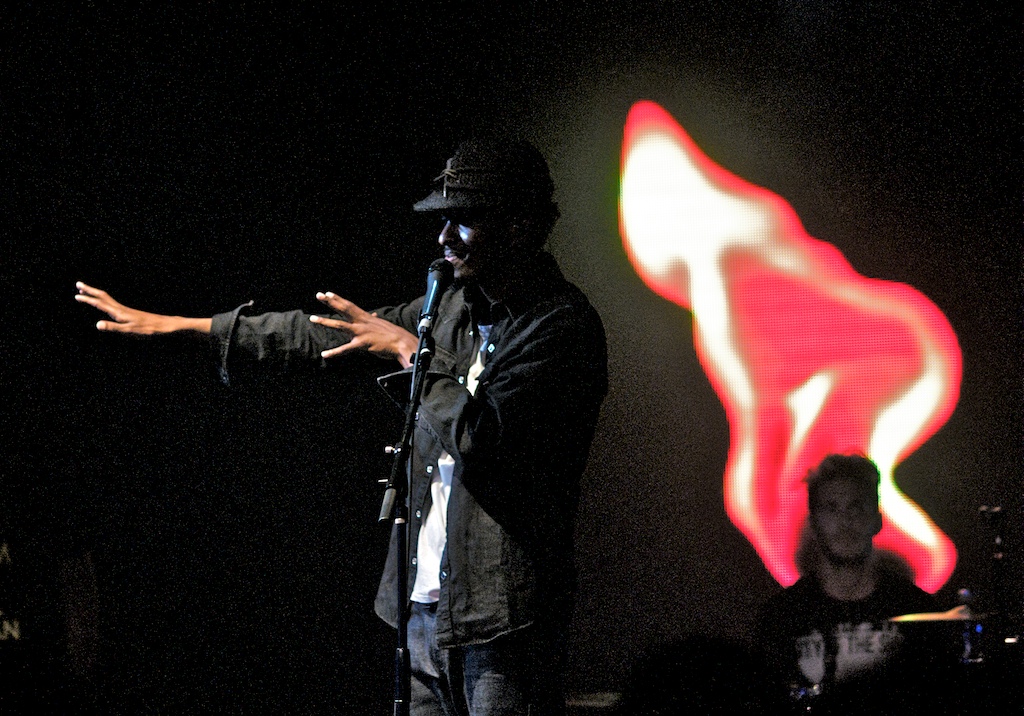

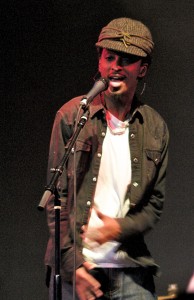

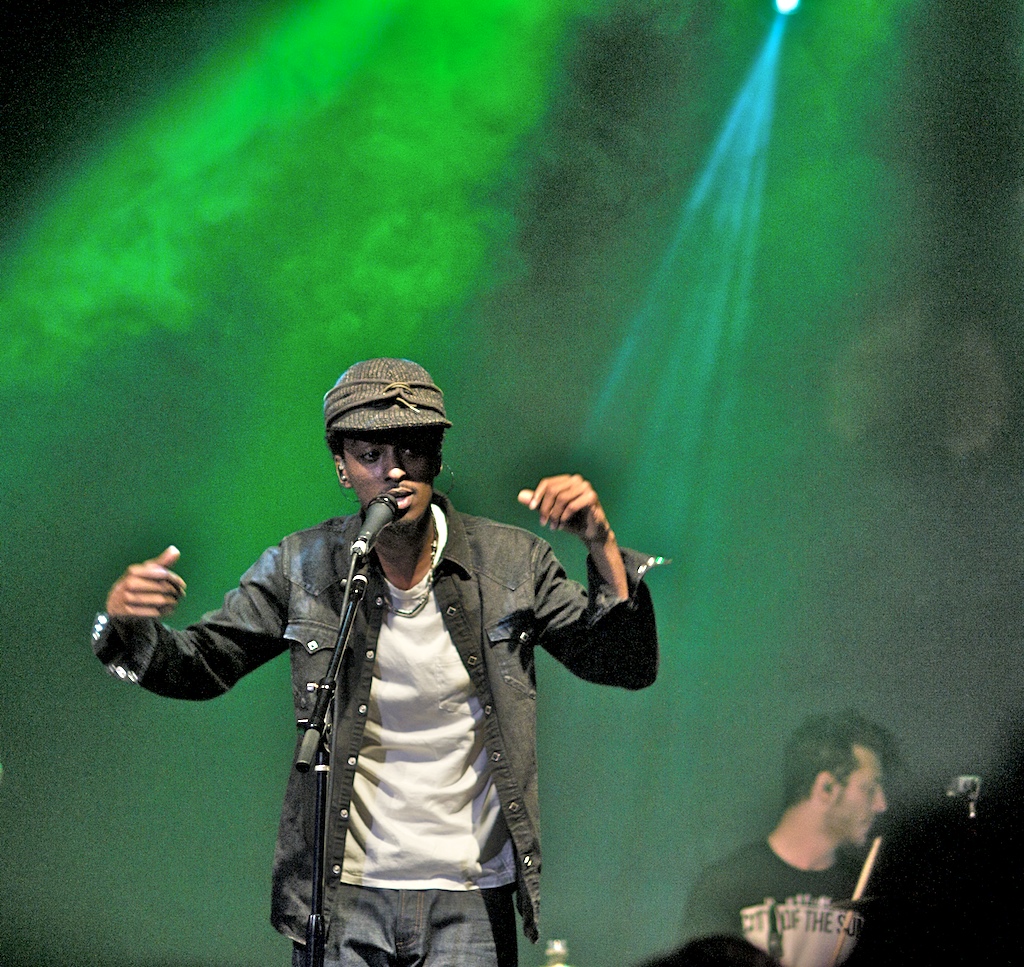

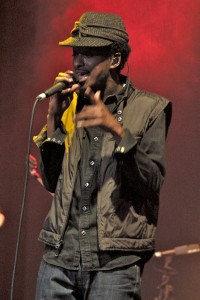

K'naan channels Neil Young's harp sound at Highline Ballroom, NYC

B.E.: You mention folk. A lot of these songs start with these kind of innocent folk melodies and then go somewhere completely different. I think that also makes you a very interesting and unique artist. You have a foot in two very different worlds, broadly speaking, and I find that you are able to translate each one to the other. There have been a lot of attempts at that, but I can't think of anyone who's quite pulled it off the way you have .

K'naan: Thank you. It's funny, because I don't really know how successfully I've done that. I've been thinking about that. I remember... maybe it was just one day, but I remember, I played this song, "Gold in Timbuktu" in a room full of artists and producers, you know, a bunch of successful hip-hop artists and rap guys in a room. And it was very smoky, like weed, and about 30 people in the room. And someone was like "Yo, K'naan has this song that everybody's got to hear." And I played the song, and I remember it floored everybody. Like just them saying, "Can you play that again? Man!" And calling people into the room. It was a beautiful moment.

But one of the artist turns to me and he's like, "Now. Now, what kind of sound is that? What kind of music is that? What do you call something like that?" And then you play that for the other side of the world, like the pop and folk and traditionalists who are different from hip-hop, and they'll be like, "Yeah, what kind of thing is that? Is that what hip-hop is?" So I don't know. I don't know that I belong anywhere anymore. It's a strange time.

B.E.: But you're also in a kind of liberated place. I think of it as kind of post "If Rap Gets Jealous." There was a certain frustration behind that song, people wanting to pigeonhole you and make you go into a certain format or comply with a set of conventions, and you resisted that. But where you are now, on one level, it seems like you'd be very free because you've achieved quite a lot of success. But on the other hand you are dealing with big labels and expectations and that sort of thing. So do you feel liberated from the kinds of pressures that you felt before, and just free to write a song like "Gold in Timbuktu" and never mind what it is?

K'naan: Yeah, I do, during the writing process, feel free. But it's everything after that makes you feel that the freedom was an illusion. When the system steps in, and the label, and the people that work with you and that are observing every step of what you do. They have to think about, "Where does this fit? Does this work as a follow-up song to the enormous success of his last song? What about American radio, specifically? Will display on top 40? Or will this play on alternative radio? Or is this too weird for any of them?" So you have those things, those questions, though severe observations that will come to your door after having written songs. You just don't know what to do about that. That's when you realize that the freedom is a bit of an illusion really. If you're working in a system, a label system, based on music business, it's really quite hard to claim true freedom.

B.E.: Well, that's an honest answer. I can certainly believe that. Again, I think you've done very well to make a statement that's incredibly individual. And I'm sure that some of the people who are huge fans of like your first record already felt that you were being massaged and manipulated with the last record, and maybe they'll continue to feel that way about this. But everything cuts both ways. You're obviously talking to a lot more people now, and that must feel good.

B.E.: Well, that's an honest answer. I can certainly believe that. Again, I think you've done very well to make a statement that's incredibly individual. And I'm sure that some of the people who are huge fans of like your first record already felt that you were being massaged and manipulated with the last record, and maybe they'll continue to feel that way about this. But everything cuts both ways. You're obviously talking to a lot more people now, and that must feel good.

K'naan: It's amazing. But it's so strange, because I don't know the people anymore that I'm talking to, because they pop up from every corner of life and surprise me. That's really, really fascinating to know that. It's not just any one particular group. The Dusty For Philosopher was so specific, because you knew the kind of people that would like that record. You knew what they were about. You knew what they were thinking about. You had a good sense of that. Troubadour was a little bit broader, even though it's still very specific, me belonging to something. This belongs to nothing but itself. And that's a really strange time. Because after Troubadour's release, I started to see people who were truly fans of Troubadour, and like "Yeah, this is what I'm really into listening to." And they would be like a Republican in the US. And I'm talking about songs like "People like Me" and "Fire in Freetown." That's what they listen to at home. So you really begin to realize the humanity in sound and music.

B.E.: Tell me about the song "Better."

B.E.: Tell me about the song "Better."

K'naan: It's one of the lighter songs, one of my light feeling songs. But it's funny because of its juxtaposition, again, with lyrics that are heavy. It's melancholy, the lyrics. The verses are, especially. It talks about my relationship falling apart. It talks about the success of "Waiting Flag "and what's wrong about that too. And all of that. And then it says I'm only getting better. I'm only working towards something greater. That's what I see in my music, in my success, and especially in my failures, I'm finding myself more and more.

B.E.: But it's quite inspiring the way that chorus comes around. I see what you mean about the juxtaposition of pain and uplift. But I just think that anyone who hears that song who is frustrated or depressed is going to get a little boost from it.

K'naan: I love that you say that. Actually, I got a call from my sister, which was really an amazing moment, because my own sister was going through something, and her best friend walks into my sister's place and she's comforting her and she says, "Hang on." And my sister is sitting there on the couch, and her friend brings out the speaker and plays to my sister "Better," that song. And my sister just broke down and cried. It couldn't get any closer than that.

B.E.: No. That's great. And this song hasn't really been heard yet, has it?

K'naan: It went out for a second. It was such a bad idea to put out an EP. We put out an EP, because the record label thought that just putting out a single is not enough news. It doesn't warrant enough attention, so if you put out other songs... And then the song choices were horrible. Because it didn't let you understand that there is a record that has a soul in it. There are songs like "Simple" or "The Wall." You wouldn't know that that record is what I am making if all you went by is the EP. So "Better" was in that. Songs are really about how you group them. It's not just a standalone.

B.E.: So the sequence is correct on this demo that I have?

K'naan: Yes. It is.

B.E.: But I understand that the four tracks that come after "The Wall," are bonus tracks, only on the deluxe edition.

K'naan: That's right.

B.E.: So if you just buy the regular CD, you'll miss out on Keith Richards.

K'naan: Yeah. I think that's how they set you up. "Keith Richards is on the deluxe. Okay, I gotta buy that." Actually, the last song, "On The Other Side" with Mark Foster is brilliant I think.

B.E.: One song that has been out there for a while, and that also has a commendation of pain and uplift, is the song with Nelly Furtado, "Is Anybody Out There?" What's the story of that song?

B.E.: One song that has been out there for a while, and that also has a commendation of pain and uplift, is the song with Nelly Furtado, "Is Anybody Out There?" What's the story of that song?

K'naan: That song went through some stages. It was like one of those moments where I was writing something--and I've only had this experience once or twice--that I know a lot of people will like, but that I didn't myself like all that much. LAUGHS It was such a strange experience, because the song is good and all that, but it's not different enough for me to love. I don't know if that's just my own strange vibes or whatever, but I only really like things that drive a new conversation forward. And that song is straight up, down the line, straight up, like a radio pop song. And because of that, I didn't really... But it's like ice skating, you know. You start and say, "Oh, man, I'm just going to go one round." And then you keep going. And the song is getting finished, and I'm watching it, and I'm like, "I know they're gonna like this. I know they're going to put this on the radio, but I myself will be like: that's okay, but it's not that great."

B.E.: Yeah, well, it strikes a very strong emotional chord. But I know what you

mean that it's not one of your more innovative songs.

K'naan: No.

B.E.: So how did Nelly Furtado get involved.

K'naan: I called Nelly and asked her to sing the chorus, after having another artist actually on the song, and then I had label problems. They wouldn't clear her. Then I called Nelly and said, "Could you rescue the song? Because the label really wants this song. They think highly of it. It's like one of those single songs. Could you help out?" And she said, "I'll do whatever you want." Then she heard the song and really, really liked it, actually. She was totally moved by it. So she gave it a real honest and beautiful performance.

B.E.: That's really true. But there's something else about that song that I think is characteristic of your work is something, and that I really like, which is this urge to stand up for the underdog. And it's another contrast with the whole puffed-up boasting of so much hip-hop. In this song, it really becomes the theme, and it works on an emotional level. When you think about that idea of standing for the underdog?

K'naan: I think I only root for the underdog. I don't much like straight up heroes. I don't really relate to them. I like side door survivors. I like people you didn't expect to have made anything of their lives or their circumstance, and who have done so.

B.E.: Of course you are one of those people, so that makes sense. Tell me about "Hurt Me Tomorrow." This is a song that you just have to love.

K'naan: Yeah, I love that one. You know, I wish -- and maybe I'll put this out someday -- I wish you could hear it the way I originally wrote it. What's out now is the radio edit, and the radio it is the only one that's going on the record, because the other one was to musical and too long to make it into a successful record, like as far as that world goes. But it was actually a pathetic attempt. It's all true, the relationship that I'm talking about. I'm thinking, "What do you want to say at this very moment to this person that you're with" This relationship is ending and you're watching it. It's inevitable. There's not any way this is going to work or last. You just don't want it happening then." So that's kind of why I wrote it. I actually wrote it so I could give her a copy of it, and nobody else would've heard it. I was going to just give her a copy. And I ended up not giving her a copy, and the relationship ending, and then putting out the song.

B.E.: Tomorrow came.

K'naan: LAUGHS. Yeah, tomorrow came, sooner than the song came out.

B.E.: It's very witty. It just makes you smile. But also, going back to Country God or the Girl, it can be applied in different ways. I have a 14-year-old dog who has been having seizures, and one of these days she's just going to be gone, and I was thinking about her and listening to that song, and it just hit me. So it works in different ways.

K'naan: That's brilliant. Country, God, or the Girl -- and Dog. [LAUGHS]

B.E.: Let's talk a little about "Nothing to Lose." I remember you spoke to me one time about your early admiration for Nas, so it must've been really great to work with him.

B.E.: Let's talk a little about "Nothing to Lose." I remember you spoke to me one time about your early admiration for Nas, so it must've been really great to work with him.

K'naan: Yeah.

B.E.: I like the verse in the song where you're reflecting on your early days in Somalia. I'm hoping to use that in my NPR review, although I have to avoid certain passages because there are words that will offend their delicate sensibilities. But tell me about this experience, and about that part where you are looking back on your early days.

K'naan: Well, I still really truly admire Nas. I still think he's one of the best at putting up songs. Yeah, working with him was genuinely one of the highlights of my music career. And I just thought, I'm sitting next to Nas, who, when I was coming up in the mid-90s, we were listening to Illmatic [Nas's 1994 debut], and a lot of the kids were making up things like where he's from. Because his name is Nasir, they were like, "Yeah, that's so Somali. He's from Somalia." So "Remember when they said Nas was Somalian," and all of that was just to reflect on coming to this part of the world and not being cool, and not knowing how to be cool yet and buying the wrong clothes, and all of that. I thought that because he was sitting there, it would be a good thing to remember around him.

B.E.: They're telling me we're running out of time. So to wrap up, I'm going to give you a quick list of artists who I somehow or other thought about while listening to this record. So just tell me whether this is someone who is hugely important -- I know some of them are -- not important, interesting, whatever you want to tell me about that. Okay, first up Dylan.

B.E.: They're telling me we're running out of time. So to wrap up, I'm going to give you a quick list of artists who I somehow or other thought about while listening to this record. So just tell me whether this is someone who is hugely important -- I know some of them are -- not important, interesting, whatever you want to tell me about that. Okay, first up Dylan.

K'naan: Oh, very important. I got into Dylan after I made The Dusty Foot Philosopher. The original "If Rap Gets Jealous" is on that record. And there's a line in there. I can't remember if it was that song or "Hoobaale." It was either the castles line, "building castles that you can't live in," or "how come they only fix the bridge after somebody has fallen?" And a BBC interviewer said, "That's a very Dylan-esque thing to say." And I said, "What is a Dylan-esque thing? I'm not familiar." That's when I was introduced to Dylan. He said, "Is even more remarkable you wrote The Dusty Foot Philosopher without knowing Dylan." Of course, that was a compliment. But I got into him then, and was floored by his work.

B.E.: Okay. Michael Jackson.

K'naan: Oh, well, Michael is important to just about everybody on the planet. I love Michael. I thought he was great. Also, I had to deal with being a teenager and having a talking voice that sounded like Michael. I was really, really embarrassed by that. I tried to deepen my voice is much as I could when I was talking to girls. And then they'd say, "Oh, he's so cute. He sounds like Michael Jackson." LAUGHS.

B.E.: This is also pretty obvious, but Marley.

K'naan: One of my great inspirations. What a guy.

B.E.: How about Paul Simon?

K'naan: Oh, man. I have a song. I wish it had made the record. It's my ode to Paul Simon. It feels so good this song. I'm gonna find a way to put it out. It's called "Don't stop now." And I really love that song.

B.E.: What about Johnny Clegg?

K'naan: I don't know who that is.

B.E.: He is a South African singer-songwriter. He's a white guy, but he got very involved with Zulu culture as a kid. Learned the language, the dance, the guitar playing. But some of your refrains remind me of his, the way you build a song up, and mixed different ideas.

K'naan: Wow.

B.E.: Check him out on the Web. He was big in France in the '90s. They called him "the Zulu rocker." But I guess we have to wind up here. So thanks very much. I hope we get to talk again.

K'naan: For sure. It's a pleasure.