In times of closed ears, misinformation and one-sided narratives, singing unsung stories can be life-giving. For Asad Abdullahi, a Somali refugee in South Africa, telling his story to the writer Jonny Steinberg was a long and painful journey. It took place over the course of two years of furtively meeting in Steinberg’s car to recount memories of brutality, loss and perseverance. Steinberg wrote a book titled A Man of Good Hope, which relayed those stories, but Abdullahi refused to read it, saying it wasn’t worth the pain of reliving those memories yet again. In Steinberg’s words, “[Asad] gave me the material to assemble a story about his personal history. But the story is not for him; it is for others.” He’s not talking about ownership—the story belongs to and always will belong to Asad Abdullahi. He’s talking about purpose: The hope is that transmitting Abdullahi’s intimate story of prolonged struggle could both offer dignity and respect to his life, and move others to prevent such realities from repeating themselves.

The heart of Abdullahi's story is in the townships around Cape Town, South Africa. Hailing from these same townships, the brilliant Isango Ensemble took on the age-old endeavor of transforming human story into theater. This February, the company brought Abdullahi’s life to the stage of the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) in a remarkable musical production, also title A Man of Good Hope. The Isango Ensemble is a stunning company of multitalented artists, most of whom hail from the Cape Town townships. Under the direction of Mandisi Dyantyis, Pauline Malefane and Mark Dornford-May, they situate old theater classics and new stories in the townships and give them new life with their inimitable musical voice that blends marimba, opera and several South African musical styles. For more background on the ensemble, see our previous post here.

A Man of Good Hope

A Man of Good Hope

At BAM, the stage was set with a perfectly simple, sloped wooden platform flanked by ranks of marimbas and backed by corrugated metal. On this warmly lit scene, A Man of Good Hope unfolded. The narrative begins as it ends: Asad Abdullahi and Jonny Steinberg meeting in a car in the township where Asad was living. (We’ll refer to Abdullahi the character as he was in this performance: Asad). Asad, played as an adult by Ayanda Tikolo, is wracked with anxiety from years of living in fear. He is a refugee in South Africa, a target of extreme xenophobia, without a consistent home or the protection of citizenship. Tikolo-as-Asad sits downstage with Steinberg, played by musical director Mandisi Dyantyis. Asad grips his leg in a panicked pose as he watches a trio of young South African men walking towards the car, the fear in his eyes a window into the trauma of his past, and a prelude of the story to come. From here, the company, all barefoot, jumps into movement as Dyantyis bounds around the stage, conducting the marimbas and voices in a frenzy of activity that kicks the story into gear. Isango Ensemble

Isango Ensemble

Asad’s life is a both a thread and a tapestry, woven into the fabric of many grand narratives yet itself spun of these same histories. His story intertwines with sagas of the civil war in Somalia, of global refugee crises, economically driven xenophobia and of hopes, dreams and resilience. The Isango Ensemble was deliberate in showing this context, beginning with an instantly captivating and accessible portrait of the origins of the Somali civil war—the history of Somali clans, grievous colonial manipulation, the jostle for power post-independence—and Asad’s position in it all.

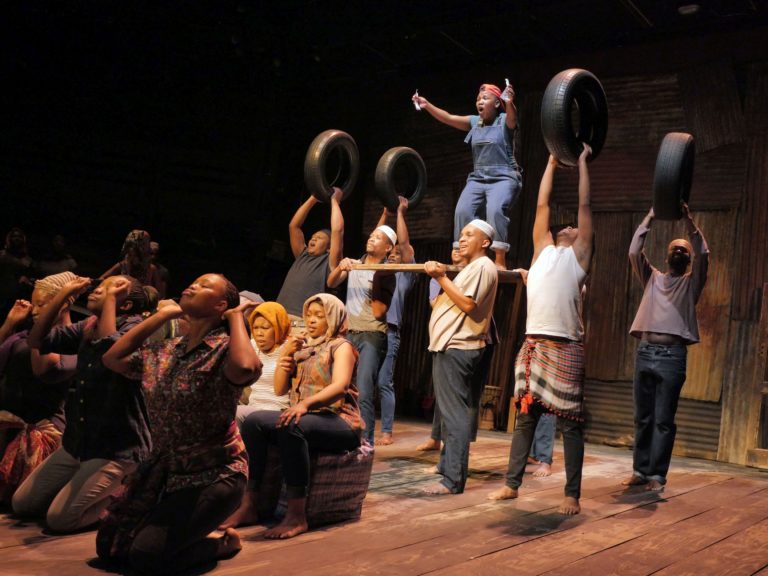

In a rich baritone, Tikolo proudly sings of Asad’s 30-plus generations of history in the clan Ali Yusuf. This dynamic scene gave a first sense of what the Isango Ensemble is all about. The company is a brilliant, sensitive and masterful collective of artists who flow seamlessly between singing, dancing, acting and playing marimba and percussion. Big group numbers show off marvelous choreography and vocal arrangements, and solos testify to individual talent. Everyone is present all the time: Those out of the spotlight are either on the marimba or drums, making sound effects, or waiting on the sides of the main stage, always attuned to and watching those at center. One can clearly feel the supportive, collaborative character of this company, whose more experienced singers mentor the less experienced. Every member worked together to develop the songs and structure of this production.

A Man of Good Hope, Isango Ensemble

A Man of Good Hope, Isango Ensemble

The company is also master of creative means to make much out of little. They work with resourceful, expressive props and sets constructed with simple ingredients and the glue of imagination. Standalone doors and frames propped up by actors give shape to an entire house, a border fence, or the bed of a truck (fleshed out with four tires and a steering wheel, all held by actors). AK-47s cut out of painted plywood still inspire terror and stacks of brightly painted boxes labeled “Bread,” “Rice,” and “Milk” construct a Somali-owned store in a township, a site of joy and tragedy.

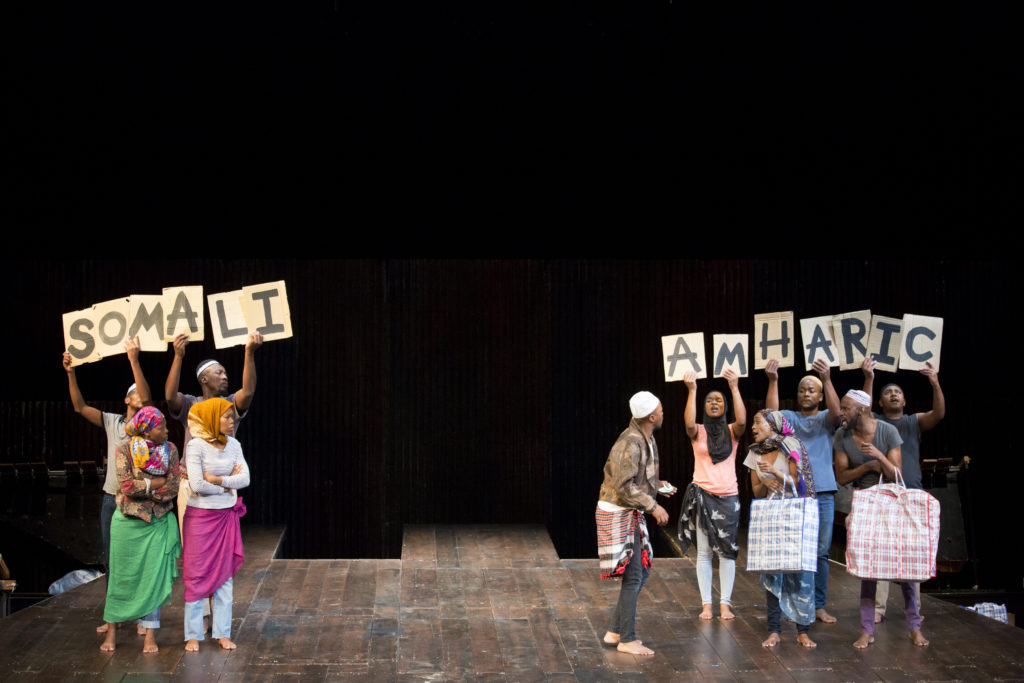

Likewise, all of the magic that shaped the production’s soundscape took place in plain sight. No voices were amplified and no sound effects were piped in, yet the performance was as richly textured and immersive as could be. The singers’ voices filled the room for operatic numbers and group songs and used the subtleties of volume to create convincing illusions of space. Their muted, sung whispers and thrown voices sounded miles away or behind walls. To bring scenes to life, the performers employed the stage, walls and marimbas for sound effects: A sharp, shocking smack against corrugated metal was a gunshot; a quick, repeated sweep up the bars of the marimba gave voice to water as it glugged out of a jerry can; and a quiet drum roll on the wood platform added visceral suspense. In a fun scene, multilingual Asad (played as a young man by Luvo Tamba) illustrates the interpretation hustle he made for himself while in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, carrying messages between two groups on either side of the stage who sing nonsense syllables while holding up signs saying “Amharic,” “Swahili” or “English.”

Isango Ensemble

Isango Ensemble

Once the frame of history has been set, the narrative shifts to the beginning of Asad’s long journey, as a young boy (played by Siphosethu Juta) in Mogadishu, the center of a Somalia torn apart by civil war. Juta, who is still in elementary school in Cape Town, embodies a young Asad with sincere emotion and a big voice. As the story progresses and Asad ages, his portrayer changes, from Juta to a young woman, Zoleka Mpotsha, to Luvo Tamba, then Ayanda Tikolo, who all wear an identifying white taqiyah (skullcap). The fourth wall in this production was wholly porous. Asad narrates his own story and dialogue flows between characters and out to the audience. Much of the narration has an exaggerated, dramatic resonance, resembling the expressive force needed to fill an opera house, as opposed to the delicate subtlety of film or small-stage theater. Though this approach could come across as overwrought for such intimate, emotional material, it didn’t feel out of place here.

Isango Ensemble

Isango Ensemble

The many Asads bring us on a journey that crosses borders out of necessity and fear, following the life of a refugee who faces tragedy after tragedy, yet remains indomitable and full, as the title tells, of good hope. Everywhere Asad went along the flank of East Africa and into South Africa, he tapped into the extended reach of his clan, finding other Ali Yusufs or friends who provided some form of support in his unstable world. Lifesavers in the life of a young refugee. After witnessing the wanton murder of his mother as a young boy, Asad is taken in by a cousin, Yindy, given voice by the deft operatic alto of musical director and cofounder Pauline Malefane. Yindy soon gets struck by a stray bullet from a sudden scuffle, sending her into a painful immobility from which Asad, still a small child, nurses her back to health. Sparked by mounting violence, the pair struggle their way to a refugee camp near Nairobi, where they wait endlessly for a way out. There, Asad learns English in an exuberant, full-company song and dance number. Later, he watches as Yindy leaves with a visa to America, where “everyone has everything and everything is good,” apparently.

He then sets off on an odyssey to find stable ground: He learns business from a kind Somali man in Ethiopia’s arid east; he works as a middleman in Addis Ababa; he is abandoned by Yindy’s family; he marries his wife, Foosiya; and he takes a risk and smuggles himself to Cape Town at great expense. Once again, he arrives in a new land, penniless but with the contact of his cousin, a shopkeeper named Abdi, who takes him in and offers him work. Here’s where the harsh conversation about xenophobia bubbles to the forefront. Arriving in Cape Town in the ‘90s, Asad immediately faces aggression from township residents. Even as the African National Congress rises in power, Mandela is freed and apartheid is ended, life is hardly different. Like the systems of oppression that persist under other names after the abolition of slavery in America, the company reflects on the end of apartheid: “1994 was the end, but what has changed?”

The economic woes, racism and political maneuvering of the time were compounded by a lack of social mobility, opportunity or political representation in the townships of South Africa. This fostered a defensive, tense atmosphere. As we’re seeing on a large scale these days, there tends to be a pervasive instinct to blame shortcomings—economic, social and infrastructural—on immigrants, refugees, and all the people that “don’t belong.” Many South Africans, themselves maligned by an unfair economy and political manipulation, turned their frustration with local inertia towards immigrants, Somali and otherwise. Those who had found a foothold in local business, like Asad and Abdi, got the most heat.

The ensemble brought this friction to life with characters who asked “How can we achieve greatness if we let Somalis in? They will take our jobs.” For those of us living in the United States, these scenes turn an ugly mirror on our country, where rhetoric is dominated by the idea that “we don’t have what we want because of the presence of ‘outsiders.’” Asad ended up at the receiving end of this attitude in South Africa. There’s a queasy dissonance that, following decades of systematic second-class citizenship for black South Africans, foreign black Africans came to bear another form of discrimination that associated them with disease, genocide and dictatorship. In a time when refugees are so often thought of in blanket terms and statistics on the order of thousands, Asad’s story serves as a potent evocation of the deep, human lives that are behind every one of those digits.

Isango Ensemble

Isango Ensemble

In A Man of Good Hope, this real and continuing xenophobia came to a boiling point when a South African neighbor and former friend turns on Abdi, breaking into his store as he washes for prayer and killing him. The killer is acquitted and ends up back on the street as Asad mourns fearfully, unsure who is friend and who is foe. He gets into an argument, showing that prejudice can go both ways, saying “I’m not black, I’m Somali. I’m not like you, I have 32 generations [of clan history], you have no history.” Angry combatants steal his truck, which he had dreamt of owning since his youth, leaving him again with nothing. During this time, many Somalis were murdered around Cape Town and thousands were displaced by the violence, sent to an encampment in a forest. Asad is again a refugee, but this time in the country that was supposed to be a refuge (again reflecting conditions in the U.S., as Somalis cross the border to Canada).

Isango Ensemble

Isango Ensemble

It’s important to point out that, even though struggle and persecution are constant threads in this story, there are also many shining moments of happiness and play. At times the dynamics were jarring, jumping between ebullient chorus numbers and operatic elegies or between jovial dialogue and utter calamity. But such disturbance was part and parcel of Asad’s story. The bright moments are brilliant but the company also excels at the dark. Fights, murders, mobs and arguments are artfully choreographed scenes of chaos, with voices and bodies swarming around the stage. Death itself is marked with somber quiet, followed by a mournful musical motif: slow harmonies intoned like the weeping of a person stunned by loss. After Asad reflects on the violent xenophobia that swept South Africa and took his cousin Abdi, Death comes to a smoky center stage lit by harsh red light. Actor Zebulon K. Mmusi, wearing an orange wig, spirals around to swelling, fearsome music. With overstated slashes of his arm, he triggers the mobs standing around him to deal fatal blows to their victims, one by one. As the music builds, he spins faster in a jerky motion, commanding his puppets to deal death over and over. The effect is sincerely shaking, gruesome in its simplicity.

Isango Ensemble

Isango Ensemble

Asad Abdullahi’s story continues beyond the world crafted so well on the stage by the Isango Ensemble. The story ends as it began, with Asad and Jonny in the car, but this time the scene continues and life steps forward—Asad finally, after many years, is given a visa to the United States. Before curtains, the script ends on a tragically hopeful note, as Asad says, “Everything will be fine in America.” Asad now lives in Kansas City.

The Isango Ensemble is an exemplary group of storytellers, bringing Asad Abdullahi’s story to life with utmost creativity and respect (although the absence of any Somali performers in the telling of this tale is conspicuous). The show’s run at BAM is over, but they intend to take it on the international circuit. Keep yourself updated at their Facebook page for details. If these words haven’t piqued your interest, here’s a clear message: If A Man of Good Hope comes to your area, do your very best to go see it, and bring a friend.

Photos by Rebecca Greenfield