Jesse Weaver Shipley is a rare one. An Associate Professor of Anthropology at Haverford College, and author of a remarkable book about new African music (“Living the Hiplife: Celebrity and Enterpreneurship in Ghanaian Popular Music,” Duke U. Press, 2013), he also directs theatre productions and is currently doing research on professional boxing in Ghana. Shipley has been traveling to Ghana for 20 years. He collaborated on one of Afropop’s first Hip Deep programs, about the early days of hiplife music. He was also in Accra during Afropop’s 2013 research trip there, and organized a unique session with Mensa and Wanlov of the FOKN Bois. The three of them improvised a comical tour of the contemporary music scene in Accra, which you can hear threaded through the program “Ghana 2: 21st Century Accra, from Gospel to Hiplife.” (Don’t miss it!) Back in New York, Banning Eyre sat down with Shipley to debrief. Here’s Part 1 of their conversation. And have a look at Shipley's recent article on the Azonto dance and music phenomenon.

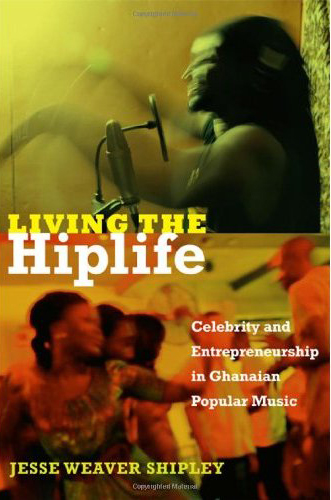

B.E.: Tell us a little about your new book, Living the Hiplife: Celebrity and Entrepreneurship in Ghanaian Popular Music. To me, it’s probably the best book that’s been written about the new music of Africa. A lot of people who have been our public radio audience over the years might need some convincing that this music has the same kind of validity that the stuff that Youssou N’dour, King Sunny Ade, and others of that generation had. I know that wasn’t your purpose here, but the book makes a strong case for this music, and gives readers a lot of ways into it. Maybe you could just make a statement about what you were trying to accomplish with this book.

J.S.: I wrote Living the Hiplife: Celebrity and Entrepreneurship in Ghanaian Popular Music to characterize what’s been happening in Ghanaian music and Ghanaian popular culture since the early 1990s. I wanted to capture a sense of the music itself—the artists, the beat-makers, the fans—but also to put it in the context of political change, the economic movement towards the free market, Ghana’s relationship to transnational circulation, the history of colonialism, corporatization, the rapid rise of celebrity culture, all sorts of things. I wanted to portray for people who aren’t familiar with recent trends in popular music what creative artists are doing, how artists are using technology, and how they’re making new music and circulating it.

Whereas older generations of musicians were using live bands, young artists are using beat-making technology. What are the struggles that they face with the dearth of instrumentation? How has hip-hop itself become something unique in Ghana? Most explicitly, I describe the birth of hiplife music from the early to mid 1990s and talk about the interesting combination of hip-hop, other African American influences like soul and R&B, and highlife, into something uniquely Ghanaian but that has a complicated set of transnational connections. And I wanted to try to convince people that this is a musically significant moment; for listeners who maybe are not particularly tuned into these kinds of styles, to show them why it’s important and interesting to listen to it. I think music scholars often work on what they’re personally attracted to and impart moral and aesthetic value to it; if they don’t like the music, they’re going to be turned off. I wanted to take a step back and not celebrate the music as an aesthetic movement, but give people a chance to think about the music in broader social and political contexts; to look at how it speaks to youth conditions—inequality, struggle, frustration—not just in Ghana, but globally speaking. So the book is about Ghana, it’s about Accra, but it’s really about the kind of contemporary moment in music as well, globally speaking.

B.E.: Let’s back up a bit and talk about the particular relationship of Ghana and the US. You look back through the cultural history—Louis Armstrong, James Brown, the Soul to Soul concert in 1971—and there are all these times when American music comes and makes this incredibly strong connection in Ghana. So maybe you can just put that in context for us. What is important to understand about the relationship between the US and Ghana?

J.S.: Going back to the early 20th century, even the late 19th century, American and Caribbean vaudeville actors, musicians, soldiers, and missionaries brought music to West Africa. And that music has been influential on West African artists. Cinema and theater from the US and UK also influenced local tastes. African American and Afro-Caribbean

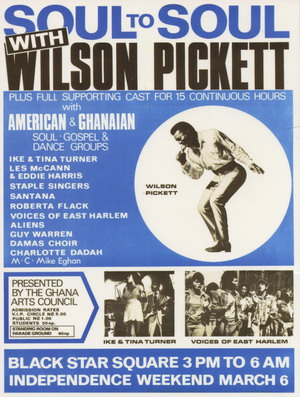

styles have been particularly influential which speaks to the complex diasporic connections that have not only shaped the lives of Africans in the new world but also African societies on the continent. Connections were made through informal as well as official channels. In the mid-twentieth century, the US government was involved in bringing jazz artists to Africa; for the US government, it was partly a propaganda move to counteract what they saw as the potential threat of African countries to align with communist regimes. So they saw jazz and bringing particularly African American artists to Africa as a way to create good propaganda for the United States. The sort of the unintended consequences of that were these great jazz musicians working with and influencing and kind of inspiring African artists across the continent. Louis Armstrong’s two visits to Ghana were hugely influential. People remember them decades later. Other less well-known jazz artists also circulated across the continent. And more recently, from the ‘60s and early ‘70s, there was a series of soul and R&B artists going to various places across Africa, including Ghana. The Soul to Soul concert in Ghana had a big impact on artists at the time, with Wilson Pickett, Santana, Ike and Tina Turner, the Harlem Singers…

B.E.: Right. A number of artists we’ve interviewed have talked about this concert.

J.S.: Yeah, Soul to Soul was part of Independence Day celebrations in 1971, and it was a really big influence on artists, on youth in general, and on style. So, it was held in Accra, in Black Star Square or Independence Square, and it was an all-day-and-night concert. And you know, you talk to people who were teenagers or twenty-somethings at the time, and they remember this as an incredible event. The styles, the kind of early ‘70s soul styles, the big lapels, polyester trousers, platform shoes, the hairdos and things like that, came from that concert. I mean people were dressing like that before, but that concert in particular was really inspiring. And artists were affected. Guitar players in particular were inspired by Santana it seems, and Wilson Pickett’s stagecraft, lyricism, and jumpsuit. The newspapers called him “Soul Brother No. 2,” after James Brown of course. And Ike and Tina’s sexuality, their incredible back and forth vocal and guitar exchanges, movement on stage. The concert had a Pan-African message of Black empowerment.

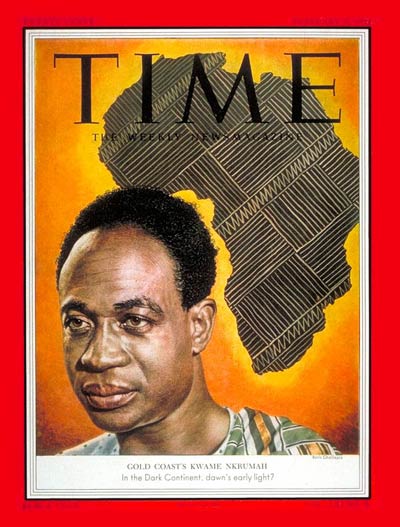

And these stars played with local artists too; Ghanaian artists were on stage. And this was inspiring politically as well, because people saw it as a kind of representation of African-American civil rights movement, and transnational possibilities and potential. So here are these artists who are American, who are successful, who are black, who are bringing a kind of black power, through music, back to Ghana. For African-American artists, it was a way to re-connect with the African continent. And it was part of a much longer movement also, of African diasporic and African American and Jamaican connection back to Ghana. It obviously leads from Kwame Nkrumah, the first independence leader of Ghana, who was one of the fathers of Pan-Africanism, politically, culturally, intellectually. Perhaps most famously, he invited W.E.B Dubois, the American sociologist and philosopher to come to Ghana after independence. And Dubois moved back to Ghana to work on the Encyclopedia Africana project. He died in Accra and was buried at his house, which is now the DuBois Centre. George Padmore, Nkrumah’s friend and mentor, also came to Ghana and when he died was buried in the walls of Christianbourg Castle, the seat of government. Later his ashes were moved to the George Padmore Library in town.

There was a symbolic as well as a political and intellectual project of Pan-Africanism. Kwame Nkrumah inspired other African American and diasporic artists to come to Ghana. He invited people very explicitly to be part of an African movement for unity and independence in the 1950s and ‘60s. And that spirit stayed on even after the 1966 coup that ousted Nkrumah, and musically, we see that in the popularity of soul and R&B styles. These are ancestors of the hip-hop movement in that they were ways that youth incorporated black diasporic styles into their lives as a symbolic form of critique of local and global marginalizations. Hip-hop is the new generation. So if you look at hip-hop today, in Ghana in particular—but you also see it also in Senegal and Nigeria, and other parts of Africa—you see the history of a kind of Pan-African sensibility in this new generation. Even if you don’t hear it in every particular lyric, there’s that kind of trajectory of transnational movement of black styles, of black political perspectives, of the possibility of black capital.

The other part of that that is inspiring to Ghana is that Kwame Nkrumah was particularly influenced by Marcus Garvey. If you notice, the Ghana flag has a Black Star and Nkrumah took this Black Star from Marcus Garvey, the really important early twentieth century Jamaican intellectual and activist who inspired a “back to Africa” movement and argued that people of African descent should return to Africa and work through the African continent as a kind of political, capitalist project. So he started Black Star Line, which was a shipping line, for people of African descent. So the idea of the Black Star, that symbol, was crucial for Nkrumah.

So if you look at the landscape of Accra, it is spatially marked by these kind of markers of Pan-Africanism; you see the George Padmore library; you see the W.E.B. Dubois Center; you see the Kwame Nkrumah Mausoleum; you see Black Star or Independence Square, which has this monument, with this beautiful arch in a roundabout and this black star positioned on top of it. So you can see Pan-African connections written onto the landscape of Accra, following it is one of the many ways you can move through the city. And then you see the kind of contemporary music landscape interspersed with that, the churches, the Islamic communities, the commercial world of markets and sellers, the old colonial bungalows dwarfed by new glass high-rises, as with all capital cities there are multiple histories written across its streets and buildings.

B.E.: There was an interesting thing that John Collins said, about hiplife, the new music. He said there’s no Pan-African sensibility in the content of the lyrics in hiplife. And I found that paradoxical, because one of the interesting things about right now is that these young artists are getting so many opportunities to travel to other countries, particularly Anglo countries--Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa--and they’re experiencing themselves as being part, not just of Ghana, but of a young African music movement. These artists actually experience a more Pan-African life than their predecessors have in the last 30 years, and yet it is not something that they feel inclined to address directly in their work.

J.S.: Yeah, it’s a great question. First of all, the political-economic context of the moment, the drive to the market right now has fostered a way of seeing Africa as a potential consumer market. Obviously this is not new but with satellite television, mobile providers, internet-based consumption and popular culture it is more intensive than it used to be. So there is a consumer and commodity oriented Pan-Africanism, if you will, driven by corporate interest that is capitalizing on older more radical Pan-African visions. As for hiplife, I agree with John that a lot of it is not explicitly political. It’s not political in the sense that one listens to politically conscious hip-hop in America, or Senegalese rap is more explicitly political in its relationship to what’s happening in elections, in the public sphere in Senegal. You hear hip-hop coming out of Palestine, out of North Africa, that has a more explicitly political valence, that is critical of inequality, racism, and state violence. Ghanaian hiplife and Afrobeats and GH rap and Azonto and various versions of popular music coming out of Ghana, while some of it has Pan-African content about uniting people, or explicit references to racial connections, most of it is much more about daily life, about celebration, about playfulness, about dreams of the future, about in-jokes, about indirect proverbial speech. Some of it is just party music.

Accra (Eyre 2013)

To me, what’s really going on is the way in which maybe an older version of Pan-Africanism, which was about political and economic connections, is channeled into a kind of market sensibility these days. I think a lot of the artists are interested in a Pan-Africanism, but a capitalist, money-making, wealth creating Pan-Africanism. There’s a kind of contradiction between an older revolutionary versions of Pan-Africanism—and we can think of Padmore’s rich intermingling of communism and Pan-Africanism, and Nkrumah’s strong emphasis on African political unity—and what I think the younger generation are interested in, which is using the market, using capitalism as a way to enter into the public sphere, enter into transnational relations, gain a voice. So the music becomes a market force, it becomes a way to connect audiences not through a sort of radical revolution, but through a kind of informal economy, and increasingly formal economies as well, through various corporate bodies.

It’s interesting to think about Pan-Africanism in relation to hiplife and Ghanaian contemporary music. Not because the music is this radical force, but because it’s engaging with this history of political-economic thought, engaging with the older generation’s soul and R&B sensibility, with independence struggles from the previous generations, with civil rights struggles, now in a new language, a language interested in engaging with local, continental and global markets, and maybe trying to appropriate the language of these markets for young African artists. I mean, I can mention some artists, like I think Reggie Rockstone’s early music has some specifically Pan-African content. Some of his early songs talk about things like skin bleaching, Black global connections, about race and morality. I think artists like Mensa and Wanlov, Panji, M.anifest, Blitz the Ambassador, who was a hiplife artist, but now is based in the US and travels in Europe a lot, and now does straight-up hip-hop and Afrobeat, are explicitly interested in Pan-Africanism, the politics of race and inequality for a younger generation, and disenfranchisement of African youth. So definitely artists are doing that kind of work.

B.E.: I think I mentioned to you the singer Efya’s comment that people don’t need artists to tell them about their troubles, to kind of raise their consciousness; they need them to help them have fun and escape, to “Get Away,” as one of her songs has it. And she defended this idea quite vigorously, which I thought was interesting. So what I see looking at the whole picture of Ghanaian music today, is this great diversity. You have a big enough panorama or artists that you have room for some political artists, some outrageous artists, very sort of socially challenging artists, then lots of straight-up party music artists, gospel in all its varieties. You know it’s really quite a diversified music scene, compared with anything that has existed in the past. And that’s a sign of cultural health.

J.S.: Maybe a way to talk about that is that, in 1992, Ghana returned to democratic rule. There was a new constitution that instituted the Fourth Republic of Ghana. That constitution mandated the privatization of media. So in 1992 there was a beginning of a movement towards the privatization of radio, privatization of television, the rise of both commercial small media houses, as well as the potential of larger corporations to enter into the market. State control over the public sphere and over music and images and things started to kind of decrease. Ghana’s vibrant scene of entrepreneurial artists in music and popular theatre, clubs and traveling Concert Party Theatre and highlife groups had been muted by the political economic upheavals of the late 1970s and 1980s. But by the mid ‘90s there’s this interesting confluence of things, where hiplife really starts to fill in a gap of local musical content—although it is barely called hiplife yet; it’s sort of Ghanaian hip-hop. But artists are starting to experiment with hip-hop, with high-life, with different kinds of music, in this moment that private radio is arising. So there’s new private radio stations coming, 1995, ’96, ’97, and they’re looking for local content. They’re looking for young artists who are Ghanaian who are making music that’s going to appeal to a new consumer market. In the same vein new, cheaply produced and easily circulated video-films take over from older Concert Party troupes.

Jesse Shipley in his Colombia U. office (Eyre 2013)

At the same time, there are also these changing technologies, throughout the 1990s, the increasing sophistication of beat-making technologies, of what you can do with a PC computer and a microphone is rapidly evolving. Hip-hop gives youth this idea that young black men coming from marginalized communities, by using words elegantly and with power, can become stars, gain fame and fortune and tell the world about where that come from. So artists who don’t have access to instruments, who don’t even play instruments, but want to become musicians, want to reach a public, can do a lot with very little. And they can make a song with two guys in a room and a microphone, and then you can burn it onto some CDs and take it to radio stations. So it’s an interesting confluence of things: new technologies, private media platforms, and the opening up of the market. And it’s also tied to this celebration of capitalism as a free market. Whereas in the ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s, there was more of a debate globally about socialism and capitalism and the potential collective social movements to support people, to bring people into a better life. By the late ‘80s, early ‘90s around the world, most people seem to celebrate the free market as the best potential way for people to engage with poverty, for eradication of problems around the world. The World Bank and IMF are very successful and stifling economic potential around the world in the name of following their strict adherence to belief in the greatness of market forces and a force of progress and moral good. Their policies in Africa have been a continuation of Cold War struggles to eradicate socialism and communism even at the expense of peoples sovereignty. To me, the ending of debates around socialism, except among a few, has moved global political debates very far to the right and made it hard for alternative political movements to gain ground. The free market begins to dominate, and that becomes a way then that young artists engage.

By 2000 so many artists are starting to put out music that is more about reaching an audience, about becoming a star, about filling a gap the older generation of musicians had not been able to fill. Because young people want to listen to what’s hip and cool, they don’t want to listen to their parent’s music. So the late ‘90s, early 2000s, this whole generation of artists is trying to cater to the generation that is born in the ‘70s and ‘80s. They want to hear what’s happening, and they want to hear the latest thing. And kids are listening to music out of the United States, out of Europe, out of various parts of Africa, but they want to hear something that’s new that’s modern, but that speaks to what’s happening in Ghana. So they’re really excited in ‘95, ’96, ’97 when Reggie Rockstone comes on the scene with his Twi rap and cosmopolitan swagger, when Talking Drums and their producer Panji Anoff and pioneering pidgin rap, and a few years later when Obrafour and Lord Kenya and VIP and Acheame start to come out with complex Twi rap built upon local rhythms and melodies; the kids are really excited, audiences are really excited, because this is hip-hop, it’s something modern and fresh, it has a rebellious edge, but it’s also Ghanaian, there’s something about the sound, the rhythm, the lyrics that speak to local conditions of life.

Since 2005 there really is a diversity of styles and artists coming out in Ghana. The music scene right now is very vibrant, there’s a lot of different artists, there’s not just one style. There’s hiplife, GH rap, Twi pop, Azonto, … people are coming out with all sorts of different names, afrobeats, higherlife…And artists and fans debate the sub-genres and their relevance.

B.E.: They say ‘Afrobeats’ with an “s” right?

J.S.: Afrobeats is a term coined, coming out of London, actually, as a way to try and talk about what’s happening in West Africa in general, to link Ghanaian and Nigerian pop to a broader African, UK, and international audience. It is a sort of marketing tool a way for DJs to package a variety of musics for audiences to listen to it all together for thinking about West African music, and putting it all together. Which I think is an interesting move. It is different that Afrobeat, the combination of funk, highlife, rock, etc. coming from Fela Kuti and others.

B.E.: Thanks for that. I’ve been looking for somebody to clear this up. When I was talking to all the Afro-funk guys, they would avoid the word ‘Afrobeat’ because to them, that’s Fela, you’re only talking about Fela if you use that word. But other people use that word in a somewhat different way. So when you slip ‘Afrobeat’ without an “s” into your list of Ghanaian new music, what do you mean by that exactly?

J.S.: I would say Afrobeat is certainly a way to talk about Fela’s music, but also that whole generation of artists who are combining funk, R&B, soul styles with highlife, with other kinds of popular traditions in West Africa. They’re doing something that in the ‘60s and ‘70s is incredibly modern and cutting edge, and combines these different transnational styles into something unique. So certainly Fela is the genius of that moment, but there are other brilliant artists doing something like that. I think, I would call Gyedu Blay Ambolley ‘Afrobeat;’ I would call Ebo Taylor, at times, ‘Afrobeat,’ among others. But to me, the genre is less important as a way to define something and pin it down, you can call something ‘Afro-funk,’ ‘Afrobeat’ you can call it ‘funky highlife’ you can call it whatever you want.

To me, the debate itself is interesting, so if you call something a particular style,

what's more interesting to me is somebody else disagreeing and saying, ‘No, that’s not what it is.’ Because that itself drives interest and helps people become better listeners because they are thinking about the elements that make up the sound. People are excited about what the music is, and they’re trying to put it into categories, but the debate itself is vibrant. So one of the things that people are saying these days is…some people are saying, “Well, hiplife has evolved; hiplife is dead; azonto has taken over hiplife.” Other people are saying azonto is the next step within hiplife, and others see it as completely different. And I’m less interested an authoritative voice saying what hiplife is, or what azonto is, or what GH rap is, or Twi pop, or Naijapop, or whatever, but in looking at the eclectic mix of styles that are coming in, and how each artist tries to place him or herself in the ears of the listener in a unique way, and put their sound out there.

B.E.: So the terminology is less important than the debate, which is a way of negotiating culture in real time. Reggie talked about Azonto as a branch of the hip life tree, as if it’s a branch of his tree that he owns [LAUGHS].

J.S.: I think debates about how to define the music and how to categorize it, are signs of excitement about the music, from fans, from artists from producers, from people trying to put on concerts or market the music to different kinds of audiences. So I think it’s really exciting that people are debating it.

In terms of the politics stuff, to me, it’s important to put the music in the historical context of political change, that Ghana becomes independent from British colonial rule in 1957, with Kwame Nkrumah as its first independent leader. There’s a series of political upheavals that happen in the country, some of which disturb what’s happening in terms of the arts, others of which further it.

Jerry Rawlings

There are two coups in 1979 and 1981 with Jerry John Rawlings at the helm. So the early ‘80s are kind of an interesting moment in that they’re seen as a revolutionary time. For some people, the early ‘80s are a really difficult time. There are fuel shortages, food is scarce, a lot of people leave the country. Many Ghanaians, are kicked out of Nigeria and return to Ghana. So it is a difficult moment. And political opponents of Jerry Rawlings and the AFRC and then the PNDC government really struggle. At the same time, it’s a revolutionary moment in that at first this is a Socialist Revolution. People in Ghana are thinking about how Ghana can be economically and culturally self-sustaining, how they can escape from neo-colonial power dynamics. It’s a kind of Pan-Africanism from the ‘40s and ‘50s to the late ‘70s, early ‘80s…if you look around at Africa, the sort of late ‘70s, early ‘80s is this moment of renewed revolutionary potential. There are young leaders coming up like Thomas Sankara in Burkina Faso, who’s this really vibrant, exciting leader, very much connected to Jerry Rawlings. So there’s this, there’s a kind of active debate about politics, about what it means to be an independent African country, and the potentials of the collectivity of the state to bring people independence mentally, economically, politically and to initiate new Pan-African connections. But by the mid 1990s, the government has shifted away from a revolutionary mindset, and towards trying to foster the free market. So that shift itself creates a shift in the public sphere. Youth are oriented away from early idealisms about the potential of revolution for political transformation towards entrepreneurship, towards creating business opportunities. As I said earlier, that move towards the free market, is the crucial shift for what happens for the hiplife music generation from the 1990s until today.

B.E.: You know, the musicians talk about that early ‘80s period as the time when live music was killed. But it was interesting, you know, I asked a lot of people about that, and Mensa, for instance, notes this real ambivalence about Rawlings. He acknowledged that many hate him, but noted that Rawlings was this real disciplinarian, and said that maybe Ghanaians needed to sort of sit up and walk straight and work hard and all this. Mensah said a lot of the things that are working in Ghana now started under Rawlings, which I thought was interesting.

J.S.: Rawlings remains a contentious figure. Many still feel that he saved Ghana from

Mensa (Eyre 2013)

further upheaval and instilled order and morality on the country, undoing corrupt networks and setting it on a path to stability. Though others think Rawlings was the instigator of violence. I mean, the US and Western powers were not excited to have radical voices like Rawlings or like Thomas Sankara take over countries in West Africa. These were young guys. They weren’t intellectuals, but they were idealistic, revolutionary voices who were trying to make a difference in their countries, who gathered interesting and passionate young minds around them. And they were trying to break people away from established neo-colonial networks where corporate powers were continuing to exploit African countries. Internal corruption had become endemic and these young, vibrant revolutionaries were trying to make a difference for the next generation. And so I think a lot of the positives that they did really, you still see today. Though others would disagree and think that Rawlings was an impediment to Ghana’s movement toward liberalization.

I think people like Sankara because of his uncompromising views, but also Rawlings, because he stuck around for a long time, took a lot of blame for things that, if he hadn’t been there, could have devolved in much worse ways. His government did this really incredible job of balancing different kind of international interests. The US and Western powers could have easily tried to go in and assassinate someone like Rawlings or destabilize the country, like they have done in many places. But I think Rawlings did a really good job of trying to maintain a balance and see what was pragmatic versus what was idealistic.

B.E.: John Collins, when we spoke, presented a well-constructed discourse on how there was a possibility in Africa for a real sort of Pan-African future and that this whole generation of leaders, Lumumba, Keita in Mali, and Sekou Toure in Guinea, represented it. There was a chance to really take the technology of the West and the communal spirit of African culture and create a new paradigm. But because, first, Africa was not allowed to be one political entity—like China or India—but had to be divided into all these separate countries, and then because all these leaders were eliminated or killed or wiped out, we end up instead with this privatist, individualist thing.

Accra businesses (Eyre 2013)

J.S.: I agree with most of what he says. Something that might encapsulate that moment of possibility and political struggle: Chinua Achebe once told me, and he said it publicly as well, that Africa was “on the frontlines of the Cold War,” and that many of the problems that we see ten, twenty, forty years after independence across the African continent, lead from the way in which independent African nation states, these young states trying to make their way in the world, were caught between Cold War powers. Some of the violence that was occurring in Africa had to do with corporate struggle, had to do with the way in which the Soviets, the United States, and European nations were using African places as proxy battlegrounds for playing out their influence in the world. In their anxiety to win a prolonged global struggle the superpowers lay waste to much of the rest of the world.

Instead of fostering new governments, or fostering democracy, countries in the global north were destabilizing countries across Africa. You see contemporary corruption in African countries now, and you can’t discount that, but you also have to look at that in terms of the history of leadership in Africa, the structural forms of extraction they inherited and how Africa was caught in the midst of Cold War politics which predisposed superpowers to oust radical young leaders in favor of authoritarian leaders they felt they could rely upon. You can see that legacy today.

Reggie Rockstone (Eyre 2013)

B.E.: Let’s get back to music and talk a little bit about actual songs, hiplife songs that are interesting, and I’d love for you to give me a couple of examples that will help listeners understand the levels of the use of language: aphorisms, proverbs, you know. I thought it was so interesting what Reggie Rockstone says, “Look, I’m a perfectly convincing Twi speaker, but there are levels of how you can use this stuff, and some of these guys who are coming along are on another level.”

J.S.: Okay, historically one of the things that I think characterizes Ghanaian popular music going back has to do with the use of complicated proverbial language, as well as a set of contemporary references. So you can look at music from the ‘60s, ‘70s, ‘80s, and one of the things that characterizes highlife songs is that lyricists are using proverbs, are drawing on proverbs from Ananse (the trickster spider) story-telling traditions, from other traditions of proverbial speaking. Nana Ampasdu was especially known for telling rich, subtle stories in his lyrics. Across West African traditions, there’s a real respect for and a valorization of elegant and eloquent speaking. Authority is given to those who can use language with precision, speak in ways that are both respectful and full of complicated references. If you are a public speaker in a chief’s palace, for example, in many of the cultural traditions across Ghana, you are going to be respected for your ability to use proverbs, for your ability to speak respectfully to those in your presence while also laying out the issues that you’ve brought to the public to hear. And that tradition of eloquence makes its way into popular music, makes its way into hiplife, into highlife, into the various strains of music that you see today.

There’s something interesting about the use of proverbs that I think is important to understand how popular music works in Ghana, which is that proverbs are indirect, proverbs are not to make some simple statement, but to make complicated statements that appear as simple poetic phrases, to insult, to praise, or to circulate philosophical ideas and life lessons. Proverbs, on the surface, make one statement, but behind that statement, there might be a whole set of references that listeners can pick from. So a successful proverb, or a successful story, or a successful song works not because it is obvious what it means to listeners, but in fact, quite the opposite. A successful song or a proverb works because listeners are not often sure what the reference is supposed to be, or are struck by how it makes multiple references simultaneously, or appears to be about something while actually addressing another thing; proverbial speech encourages metaphoric thinking. So listeners and musicians and people in power debate the meaning of that song, debate the meaning of a proverb. And in the debate itself, you see a song’s popularity working. Music often circulates through controversy and disagreement, which often makes it popular.

B.E.: That’s great. The one artist we met who really did talk about his songs and did give some good examples of that was Ebo Taylor, but he’s talking about things in the past. Maybe you can give us some more contemporary examples.

J.S.: Okay. Let me first talk about it in terms of the history of the hiplife stuff. Reggie Rockstone is a crucial figure in the birth of what becomes hiplife music, and contemporary popular music in Ghana in general. He’s really seen as the godfather of hiplife, rightfully so, because he popularizes a particular style, and is the initial proponent of this kind of music. Partly Reggie’s popularity and his brilliance comes from his use of language. Reggie mixes English, pidgin and Twi in very innovative ways. His rhyme patterns, the way that he uses lyrics was exciting for young listeners, because he was really the first person to add a hip-hop inflection to Twi language lyricism, with the use of local kinds of references and things like that. But Reggie isn’t using Twi in a kind of traditional way, he’s using Twi and pidgin and English in a more kind of cosmopolitan, urban mix, in the way that kids in Accra intermingle these languages—code-switching in very interesting ways.

Obrafour

The second generation of hiplife artists are the ones who really use Twi and use other Ghanaian languages in rich ways. Someone like Obrafour is innovative in the way that he used more proverbial Twi for hip-hop, he speaks very elegantly. Listeners where at first struck by this young guy speaking with great wisdom over a beat. He used proper Twi but he had dreadlocks and a hip-hop sensibility. His first hit song, ‘Kwame Nkrumah’ was revolutionary, because he was very young at the time when this song came out, but he was using proverbial speech, he was using recognizable proverbs, he was using respectful forms of address, and he spoke Twi like someone who was much older, listeners would say. It references older forms of poetry, older forms of speaking, and uses proverbs in this way that he wasn’t mixing language. There were some English words in it, but it was much more what people would call more “typical Twi.” And that got older and younger audiences to listen and to say, ‘Wow, you can do hip-hop, but you can do it in ways that celebrate and reflect the eloquence of Akan language use.’

Also groups like Achyeame, which consisted of Achyeame Kwame and Achyeame Kofi, were really interested in using more typical Twi usage. Kenya was another artist in that generation of artists who was using Twi in this really powerful way. They broke open the market showing the potential for kids who didn’t speak English to rap; Reggie could rap in English and a lot of kids in Ghana couldn’t do that. So the potential to rap in Twi or Ewe or Ga or Hausa or Dagbani, suddenly opened up the possibility for a whole generation of youth to think about the linguistic traditions that they’re from and bring that into a hip-hop idiom.

B.E.: Now all of this is in strong contrast to a very different phenomenon, the straight up imitation of American rap. Can you give us a definition of LAFA?

J.S.: LAFA stands for ‘Locally Acquired Foreign Accent,’ and it’s an interesting phenomenon that people make fun of. People, the youth in Ghana, will sometimes

put on airs, and there’s a kind of pretense to having traveled abroad, so you say someone has a ‘Locally Acquired Foreign Accent,’ mean that you haven’t traveled to Britain or the United States, but you suddenly start using slang, you suddenly start speaking like someone who’s from America, or been to America, you dress in foreign styles meanwhile maybe you haven’t traveled outside of Accra. But it gives you kind of local cultural capital, it gives you a sense of being cosmopolitan and hip and international. You know, if someone is doing that, then other kids might make fun of him for putting on airs and things like that. It is a way for people to talk about and debate authenticity, what is local and what is foreign. There is a lot at stake in language use, in how you use words in your inflection; it reflects class, it reflects long-standing debates about national language, the relationship English has a colonial language, and the role of African languages in shaping a modern African nation-state.

B.E.: It is an interesting contrast. Let’s come back to what you were saying about proverbs and local language.

J.S.: So in hiplife and hip-hop and popular music in Ghana, there’s a use of proverbs, some of which are recognizable proverbs from other contexts. The other thing that a lot of musicians will do is they’ll use the proverb structure to make certain kinds of statements. Many people are critical of the fact that a lot of music is about objectification of women, about sex, about playfulness and partying and things like that. So some artists if they want to talk about sex, if they want to talk about something controversial, they will do it in a more indirect way. They’ll do it through a statement that may be about sex or may not be. Artists want to talk about certain things without being seen as overtly disrespectful.

...to be continued. Check back at our website for the second part of this interview.