Margaret Lou Brown is a cultural anthropologist at Duke University. She began working in Madagascar in the early ‘90s. Before the Afropop team went to Madagascar in spring 2014, Banning Eyre had a discussion with Dr. Brown about her work and insights into the history, culture, politics and social life in Madagascar. Here’s their conversation.

Banning Eyre: Thanks for speaking with me. To start, tell us a bit about your work in Madagascar

Margaret Lou Brown: I spent many years doing research, primarily in the northeastern part of Madagascar in what’s known as the Sava region. I did work on community politics and land and ancestors and family politics. Later, I went on to work on an applied project with a conservation organization. Since then, I don’t have an active research agenda in Madagascar on the ground, but I do work at Duke where there’s a strong interest in the biodiversity of Madagascar, and I also maintain ties to the social science research group that works in Madagascar, so I continue to keep tabs on what’s going on over there. So my interest in Madagascar has always been in figuring out how Madagascar fits in the contemporary world and global economy and global politics, global culture.

When I was working in the northeast, one of the projects I worked on involved the vanilla market. When most people think about Madagascar they think about the pictures they see of poor farmers burning down forests and living off the land, which is what the majority of people in Madagascar do—they live off the land. They don’t burn down forests, but they do live off the land. But there’s another side of Madagascar that’s very involved in the global economy in multiple ways. Even some of those farmers that live off the land are growing things that are sold to make ice cream for us or, at one time, Coca Cola, and other products. So Madagascar is the world’s biggest exporter of vanilla and, the way that works, it’s not just the farmers growing things on the ground, but it’s also these big economic players—Malagasy exporters, who are going to big meetings in France and going all over the globe selling their products.

So there’s another side to Madagascar that’s very much entrepreneurial and wealthy, interested in exporting their ideas, as well as their products in other parts of the world, particularly in France, but also in the U.S. and Canada and other parts of the world. So that’s something that I’ve been really interested in is seeing how Madagascar is not just this isolated island off the African coast, but also a place that’s really connected to the world and has been for a long time.

One thing people are really interested in, because of Madagascar’s rich biodiversity, is how it first became settled. That’s kind of a driving question. It’s a fascinating mystery and, hearing archeologists talk about their work, it really is an exciting time to be doing archeology in Madagascar because, for the longest time, the prevailing wisdom about Madagascar’s settlement is that humans didn’t arrive in Madagascar until about 500 A.D., so that’s a very shallow time frame for human population on the island. And that’s been tied to stories about the destruction of habitats and the extinction of species, but what we’re now beginning to learn is that around 500 A.D. is when the first larger human settlements—village-type settlements where people started to practice more settled agriculture—that’s when that started to occur. But humans arrived in Madagascar probably much, much earlier than that, so the earliest archeological evidence now puts humans in Madagascar at about 2000 B.C. So we’ve gone way back.

It’s amazing stuff and the evidence is pretty good. The paper was published in July 2013 by a team of two well-respected American archeologists [Henry Wright and the late Bob Dewar] with a team of Malagasy archeologists. And it’s not unexpected when you think about how what we know about human settlement changes over time. The early, early settlers were probably hunters and gatherers, foragers, and they don’t leave a really rich archaeological record, not a dense record in any one place. So it’s harder to find that kind of material and that explains partly why we haven’t seen much evidence. We weren’t really looking for that because there was a story about Madagascar’s settlement and it kind of fit in the narrative. But now that’s being challenged and there’s a lot more archaeological work to be done and, happily, a lot of it is starting to be done, for example by young researchers like Kristina Douglass from Yale.

That’s fascinating. I just want to interject there for a moment because I’ve been reading Mervyn Brown’s classic, perhaps out-of-date book [A History of Madagascar, 2002].

Right. It’s a good book, though.

It’s lovely, and he writes about the first human arrivals. He says that, with the technology, the knowledge, and the boats they had, they probably couldn’t have come across the open seas. They must have taken some more circuitous coastal route. He says they must have come in small groups, not en masse.

Yes. And that’s a really interesting thing. But I would say the current thinking is pretty muddled. We still don’t have archaeological evidence of a particular national or language group. That doesn’t really survive in the archaeological record so much that you can clearly show an Indonesian or African influence. The primary evidence for people of a particular origin has been the linguistic information. Also, pushing back into time on this point about what technology would have been required to get there, I believe it’s still the common thinking that the first settlers came from Indonesia instead of from Africa. But what I’m hearing from archaeologists now is it’s likely not to be a neat story in the end. There were probably multiple arrivals—as you say, not en masse in any way. There may have been people arriving from Africa at the same time that people were also arriving from Indonesia. The archaeological record is pretty sparse right now. The whole west coast of Madagascar still needs to be explored archaeologically and it’s likely that that’s going to turn up some new information that’s going to challenge this idea of a single origin of people. Now, they talk about mosaic, that Madagascar’s prehistory is a prehistory of mosaic, and its history of course is a mosaic history. I really like that term to think about what Madagascar is.

Let’s move on to language and culture. Brown writes about cultural unity versus diversity on the island. There is, more or less, a single language across the whole island, and Brown links this to the relatively short period of human history. There hasn’t been enough time for languages to really differentiate. But there are somewhat distinct ethnic groups, aren’t there? But they share similarities in their religious practice, their architecture, and the language. So how do we think about this simultaneous differentiation and also surprising unity across the island?

That’s a great way to put it—differentiation and unity. On the language, linguists are still working on that. Yes, there is an official Malagasy that is generally known as the Merina dialect, the one from the central highlands area. That’s what you’ll see in most written Malagasy. Then there are these other dialects and they are very similar structurally, mutually intelligible for the most part, although one of the things that’s interesting is that, because of different pronunciations and different speeds and different styles of dropping words and things like that, it’s often not as mutually intelligible as you would think based on the structure. This is something people comment on frequently. They think they should be able to understand the Betsimisaraka dialect, for example, if they know Merina, but it’s not as easy as it seems.

So this is a living language. Betsimisaraka people, if they’re writing, they’ve learned to write in formal Malagasy, in the official dialect, and so you get this kind of challenging break between the language people are using when they speak and when they’re pushed to formalize it. And this goes back to old hierarchies on the island about Merina domination during the Merina kingdom and then French domination, which also formalized that particular form of Malagasy, as well as French. So Malagasy is structurally understood to be a single language with these multiple dialects, although there are some Bantu influences, and one particular group on the west coast tends to have much stronger Bantu influence. On the east coast where I worked with the Betsimisaraka there is a much stronger mix of French, for example, sprinkled in with Malagasy. They are much looser, it seems to me, about allowing imported words into spoken language and into their communication.

Why do you think that is true in that particular area?

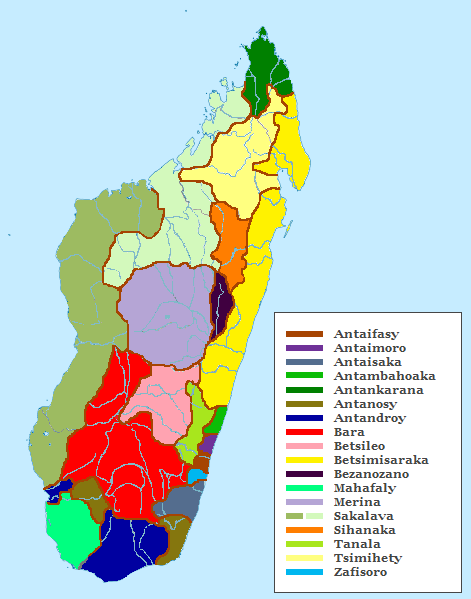

A few things. I think the coastal areas were more heavily influenced by the French. Historically the central highlands region became the British stronghold for a while, so that was the heavily Protestant area of Madagascar, and that’s where the London missionaries had the strongest influence early on. In the coastal areas, the French and British were struggling, so French had a greater influence and a greater hold and that’s why Catholicism took off more along the coastal areas. So that historical trajectory continues to have influence today, although a lot of things have mixed up. I also think the coastal regions were not as hierarchical in their own internal structure. Basically, when you think about the history of Madagascar’s ethnic groups, you have the Merina, who are known to have had a very strongly hierarchical structure with a king, and various castes beneath the king—you had royalty and non-royalty. And with the Sakalava, the same thing. They were on the north and northwest primarily. Then you have other groups like the Betsimisaraka, primarily along the east coast.

I think two things were important about many of those groups. One: their structural organization was much looser. It wasn’t as hierarchical. They tried, but failed most of the time, to really develop a kingdom structure, so they weren’t very successful at developing a strong hierarchy. And two: for various reasons—some of them having to do with the power of the Merina and trying to get away from Merina influence, others having to do with Merina influence forcing people to move—these areas have seen a much more fluid movement of people. That kind of movement encourages people, maybe requires them in some ways, to be open to other influences and absorb a lot more influences as they encounter different people and engage with them in different ways. Does that make sense?

It does. It makes me think we need a bigger picture. How would you describe the overall ethnic makeup of Madagascar?

Yeah, I hate that question. [Laughs]

Sorry!

Well, generally speaking, we talk about 18 different cultural groups in Madagascar. That’s kind of been the conventional wisdom or the historical understanding, and I think in many ways that still holds. Some groups are quite small. Others are large and very multiethnic in their makeup, but still have some strong features that identify them. The biggest influences on the island, in terms of having control over other groups, have been the Merina, which are associated with the central highlands. So the famous kings and queens of Madagascar were all Merina. And then you have the Sakalava, who I mentioned. They were more in the north and northwest. And then there are these other groups, like the Betsimisaraka, the Makoa, who traditionally are known as the descendants of slaves, the Tsimihety, the Antaimoro, the Mikea, the Bara, the Betsileo, the Antandroy, a whole list of them that you can find. And those groups were historically associated with particular regions in Madagascar and also with particular cultural practices. Of course over time this has all become much more fluid.

In many ways, ethnic identification is not something that carries a lot of weight in Madagascar today, but it hasn’t entirely been erased. Even back in the early 2000s when I was conducting research on the village level in rural Madagascar, you could ask someone what their background is: what kind they are, that would be the way you’d ask the question. And they would tell you. But what’s funny—at least for many of the people on the coast and among the Sakalava and Merina—everybody will tell you that they have multiple ethnicities. That’s because of one of the great and fascinating intricacies about Madagascar’s people. They trace their identity through both their father’s and their mother’s lines. So a woman doesn’t lose her ethnic identity when she marries, and her children carry her identity with them. So if I were to ask a child what kind they were then they would say, “Well I am, for example, Betsimisaraka from my father and I’m Makoa from my mother, or I’m Antaimoro from my mother.”

And it’s important to them that they remember those things for many reasons, practical reasons. Different ethnic groups have different taboos about what they can eat and what they can do. Different groups might have their tombs in different places. But it’s not just about where they might be buried one day; it’s also about making sure that they continue to honor the people who came before them. Honoring the ancestors is still a very important part of life in Madagascar. And it’s not a backwards kind of ancestral worship, but rather a forward-looking ancestor worship. For people who take it seriously, ancestor veneration in Madagascar requires you to be a particular kind of person in the present, for a couple of reasons. One is that you don’t want to get the ancestors mad at you because they might curse you, and bad things will happen. There’s certainly that side of it. But another side of it is that you want to be honored by your descendants. So you want to be the kind of person that your children and grandchildren want to do good things for. They want to be successful in life; they want to have cattle; they want to have rice. So it’s actually a very forward-looking way of living to be ancestor-focused. I think it’s kind of surprising for people to hear that, but I think that’s really important.

That’s wonderful. I hadn’t really thought about it that way. Let’s talk specifically about the tombs. If you drive around Madagascar, you notice tombs everywhere, and they differ from place to place.

Yes. In Madagascar you will see tombs, and it depends on where you are what those tombs are going to look like, and even whether you know that’s what you’re seeing. The ones that people are most familiar with are probably the ones that you see in the central highlands, and those in the south of Madagascar are pretty large structures as well. These are places where the ancestors would be buried, and they have to be cared for in very particular ways and by particular people. There are ritual practices that need to be followed.

In some groups burials are less ostentatious--I guess that’s a way to put it. You know that there’s a cemetery there, but it’s not that much more noticeable than a modest cemetery in the United States would be. So there are different funerary practices in that regard, but a pretty common feature throughout Madagascar is this need to return to the burial site after a certain number of years. Usually it’s about seven years to return and turn over the bones. So you bring out the body again. By this point it has dried and there are just bones there. The body was originally wrapped, so you unwrap the body and you put fresh cloth on it and you have a big celebration that involves lots of rice and maybe the killing of a zebu [cow] and sharing it with the community. So it’s a big communal celebration, a big extended family celebration. This is the event they call famidihana.

The ones that I’ve observed—and I’ve seen some in the highlands, as well as on the east coast—involve not just family members, although family members are expected to come from all over, and by family I mean really extended family. So you’d go several generations across and also community members. Maybe everybody in your village would be invited, too. So it’s a way of cutting across the family distinctions and pulling everybody together to celebrate, and to display your appreciation for this ancestor and all that they’ve done for you. This is part of what killing the cattle is about, part of what the rice is about; it’s to show that you’ve had a successful life and and to demonstrate that you believe that this is at least partly in thanks to what the ancestors have done for you and left for you. So it creates… I hate to use the word incentive, but I do think it does that. It creates an incentive for people to accumulate some wealth during that time and so that they can have this ceremony. It is a source of pride to be able to do this and do it right, to have a big all-night celebration and turn up the bones and just enjoy the fact that you have this wonderful family.

From the ceremonies you’ve seen, what was the role of music in them?

Music plays a big role in those events. It’s basically traditional, but it becomes hybrid. So you’ll have traditional Malagasy instruments—the valiha, the drums—and sometimes mixed with a boom-box playing some music on the radio. Up on the east coast is the only place where I’ve actually seen the all-night celebrations. There they have a celebration immediately after a funeral, immediately after someone has passed, as well as the celebration a few years on. It’s an all-night party basically. And what I’ve seen is they put down boards that make the dancing more lively and loud and add that rhythmic aspect of the music is from the dancers’ feet beating on the wood, as they do the traditional Malagasy dances. So it’s not just the music, but the music inspires this dance and the dance involves both the men and the women. It’s fairly ritualized dancing, though, as the night goes on it gets a little bit less ritualistic because it does involve alcohol too. I’m not aware of particular songs that needed to be played so much as it was just important that music be played and that it involved these instruments.

I am not sure we’ll get to experience anything like this as we’ll be moving fast. But we will be with French ethnomusicologist Julien Mallet in the southwest, in Tulear. The tsapiky funerals he is studying sound very much of a piece with what you’ve just described.

Julien should be great. He should be really terrific for this.

No doubt. You mentioned that you had more to say about how ethnic identity plays out in Madagascar, racially.

Yes. Just briefly on the racial stuff, because you can’t miss that there are different phenotypes: people look different in different parts of Madagascar. And people who live on the island comment on this and it matters in interesting ways. When I was doing my research, I was trying to figure out how these different ethnic groups mattered—you know, who you could or could not marry, what do you know about someone who’s Betsimisaraka, what do you know about someone who’s Betsileo? And one of the things that struck me is that people started by describing things fairly physically. So it’s like Betsileo are lighter skinned and have straight hair. And Betsimisaraka or the Makoa—the Makoa in particular—are dark skinned and they have kinky hair. That seems like such a crude way to divide people, but it didn’t mean good or bad. It was just a descriptive thing.

It does still map in interesting ways to matters of economic power. The lighter-skinned people of Merina and Betsileo descent tend to live more in central part of the country have tended to be more dominant economically, both on the island and in external relations. If you think about the traditional Madagascar diaspora around the globe, it’s primarily those people who you would see, say, among the sort of bourgeoisie of France. Maybe some of those people have come to the United States to study. Of course, there are exceptions, but that’s kind of the general trend. Even now, people think of darker skin as being associated with the more impoverished groups—the people who live on the coast, who live more off the land, or maybe the fishermen on the coast.

These distinctions have also served people who have an interest in keeping people divided in Madagascar, playing off those differences. The French did it. They kind of aligned with the coastal people and specifically played on the cleavage between the Merina and the coastal people, and political parties post-independence did it and continue to do it. So you have a kind of black power movement or anti-Merina, anti-fotsie movement among some of the political parties in Madagascar. You have seen some black nationalism that picked up on the black power movement in the United States, some pan-African movements that have played on race issues. So it’s something that is always there and an opportunity to be used in negative ways.

It’s also something that in everyday life many people just don’t pay attention to at all. The groups do intermarry. There are no formal restrictions against marrying across groups, however there seems to be a tendency in all cultures at all times that people with wealth and power want their children to marry other people with wealth and power and that reinforces some of these problems. In the current diaspora, this is changing a little bit because there has been some outflow of lower economic class people. For example, there’ve been some prominent stories in the last couple of years about domestic servants in the Middle East. Madagascar has been part of that global story that we hear more of when you think of South Asian migrants and stories of domestic labor abuse in Saudi Arabia, or in Kuwait. I think that just in the last year or so, Madagascar and Nepal both stopped encouraging migration to Kuwait. You might want to take a look at that.

Interesting. There are a couple things I’d like to pick up on there. First, the received wisdom about the popular music of the northwest, called salegy, is that it has more African influence because it comes from these coastal people. They are closer to Mozambique and therefore more African—darker-skinned people, with a more African culture, and so on—and you can hear that in the music. But the historian Pier Larson told me when I first contacted him, “When you go there you should really push back on that idea and say, ‘Show me the evidence. What do you really mean by that?'” He was resisting that sort of easy analysis. Any comment on that?

Well, I would agree with Pier on almost anything. It’s always a good idea to resist the easy conclusion. Madagascar is a really complicated place and I think people do want to draw these neat connections: people are more African, so the cultural traditions are going to look more African there. But because there’s been so much fluid movement all over the island for so long now, you’d be hard pressed to say that there’s a continuing tradition of, you know, African music in one area. There’s just been so much other influence in those places. And it comes from all sorts of locations also. In the North, you’ve got not just African and Indonesian, but Indian and Chinese, the Italians and the French…

Arabs.

Yes. All of it has had an influence. And so, yeah, be open. You’re the music expert yourself, so listen for the sounds yourself and try to figure out what’s going on. And also ask yourself if that’s an interesting question. I say that and laugh because it’s something I’ve been thinking about a lot lately, partly because of this new archaeological evidence. Why does it matter so much to us to make these links between Madagascar and other parts of the world and these origin stories? It’s a question. I don’t really know why, but I think in some ways it’s been a paralyzing state of affairs. That sort of question has driven a lot of research in Madagascar and it’s also driven that a sort of understanding of Madagascar that has closed people’s minds to thinking about it in more culturally rich ways.

That’s very good. You mentioned the diaspora, and I remember something else that was said a lot when we were there 13 years ago. People told us that it’s really really hard for Malagasy to emigrate because of their religious beliefs. There’s this physical connection to the land where your ancestors are buried, and that makes it especially difficult for Malagasy people not to live in Madagascar. Do you have any thoughts on that?

I think that might have been true at one time. A lot of people do leave Madagascar and go back. Gosh, even in the ‘60s and ‘70s, there were these ties to the Soviet Union. I met so many people who went to the Soviet Union to study, became engineers and things like that, and came back to Madagascar and, of course, could find no work using those skills. They might end up working as waiters in hotels or drivers—things like that. So I do think there’s a strong pull to stay there. I also think a couple of other things limit emigration. One: it’s an incredibly expensive place to leave. That might sound kind of trivial, but it’s really not easy to go many other places from Madagascar, and I think that’s a significant fact. And it’s been that way for a long time. They don’t have a lot of airlines. It’s been a monopoly airline situation for a long time, so you don’t have much competition for travel in and out. And you pretty much have to fly to leave.

Secondly, I also think the education system has limited peoples’ possibilities in the global world. This has ebbed and flowed, but Malagasy is not a language that’s spoken anywhere else in the world, and so if you don’t learn French in the schools then you’re limited in where you can go in the world. And even French is not spoken that many places you might want to go. English has just recently become more commonly taught. So I think there have been multiple kinds of limits. It’s not just the cultural traditions. Real economic and political choices that Madagascar’s governments have made have set constraints on people.

Understood. And of course this relates to music, because one of the things we’ve been looking at is why so little Malagasy music has been able to have much of an impact and audience here. We think it’s extraordinary and wonder why this is. The cost of travel is certainly one reason. But there’s another—and this is kind of a pet theory of mine, which I’d love you to comment on, if you would. We’ve been covering how African popular music penetrates the American market in the last 30 years or so. When you do that, you can’t miss this incredible preponderance of successful artists from West Africa, especially Mali, just dominating record sales, concert bookings—everything.

Yeah.

And people are always asking, “Why? Why Mali?” Some say it’s because the government and media there have supported and developed local music much more than in countries like Madagascar. Some say it’s because Western gatekeepers and music stars got behind it. But I think there’s a deeper reason that has to do with history. Most of the Africans who came to the United States came from West Africa and particularly during a time when there were wars going on in Mali and a lot of people were being captured as slaves, taken to the coast, ending up in New Orleans or South Carolina. These are the people who gave us the banjo, created the blues, ragtime, jazz, later funk, rock and hip-hop. When we hear a lot of West African music, we sense this connection through history, even if we don’t think about or understand it. But when you hear Malagasy music it’s equally intricate, equally beautiful, equally surprising, in my opinion, comparable by any objective musical standard. But Americans find it harder to relate to the rhythms, the melodies, the phrasing. The whole underlying musical sensibility feels more alien. Any thoughts on that?

Yeah, it’s interesting. I think there’s a lot to what you said. There are a couple of things I would add to that. For reasons you would know better than I, music from Mali also captured powerful people in the music world, and they attached themselves to a narrative about that music that became this kind of reinforcing. When you have famous musicians who have gone to the Festival in the Desert, for example.

Yes Robert Plant, Bono, and before that, we had Ry Cooder recording with Ali Farka Toure.

Yeah and you have the Rolling Stones going to Morocco. All these people helped that story, so others jumped on that story and told that story. They retell that story, and it’s really created this outlet for people, who may or may not feel the rhythm.

And I would argue that the reason that they are attracted to West African music in the first place has to do with the historical, cultural DNA I’m talking about.

Right.

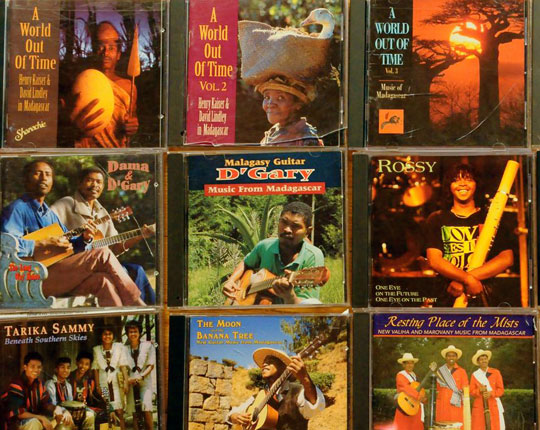

And when they create the things they do, they are successful. By contrast, look at the moment when Henry Kaiser and David Lindley came and recorded in Madagascar in the early ‘90s. They had a moment, and it created an opening, but it faded pretty quickly. It didn’t have the same resonance with people.

Yes. I think that’s true. I also think we don’t know very well the story of the Malagasy slaves who were brought to America. There was an early potential for Malagasy influence in North America, but that hasn’t received much attention. It’s something that I’d love to learn more about myself.

I’ll be talking to Wendy Wilson Fall about that. That is both her personal history, and her area of study. I’ll be curious to know what she makes of my theory.

That’s super. But I also think one of the things that makes Madagascar interesting and also problematic is the challenge of selling Madagascar as a place, an idea, a culture, a place people want to find out more about. I was thinking about when you were talking about African music. There are people who, when you tell them that you do work about Madagascar and call yourself an Africanist, they will say, “Well, you’re not an Africanist. Madagascar’s not part of Africa.” And you know it’s that Indonesian influence. You know, is it an African country? Is it not an African country? Geographically, it’s right there, but culturally people aren’t sure. It’s got this really ambiguous status, and so it hasn’t been fully embraced in the African world as a place that that is part of them. Malagasy people themselves have ambivalence about being called African. I was told, you know, that we’re not part of Africa many times when I was working there early on. Trying to figure out where Madagascar comes into peoples’ imaginations I think is a really interesting challenge for them. As these musicians and artists try to find their place in the global world, people just don’t quite know what to do with them, and dealing with complexity isn’t something that the human mind does as well.

Especially these days. We want everything very simple, and Madagascar just ain’t. That’s an excellent point. Of course, from our point of view at Afropop Worldwide, it’s all African. We take a very broad view. We covered hip-hop in Lebanon last year, and we did a lot of work in Egypt a few years ago. Egypt really is part of Africa, and yet there are many people there who also do not consider themselves African. They consider themselves part of the Middle East.

Right. Right. Exactly.

Even in Sudan—the same thing. But, well, from our point of view, it’s all Africa.

And that’s great.

Exactly. Anyway, thinking that way makes life easier for us, but I understand that for other people it’s more complicated. I suppose complication is where you find it.

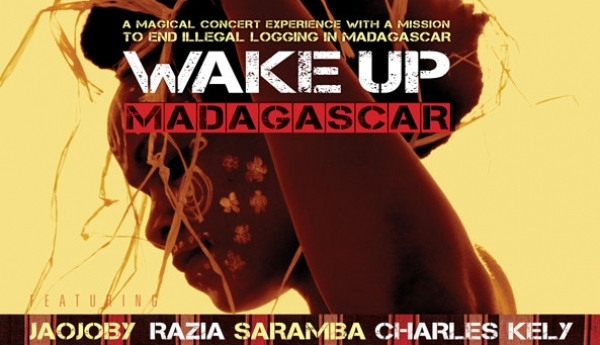

That’s true. And I think, you know, when Razia Said organized the Wake Up Madagascar tour, that was an incredibly hard thing to pull together, logistically.

Absolutely, but not hard enough to prevent her from doing it again in the summer of 2014.

That’s great. I think it’s hard to get audiences for precisely the reason you’re saying: People don’t know the music. But that particular tour should bring people to the music and maybe that will be a way of introducing people to this other sound. I think her music is very accessible.

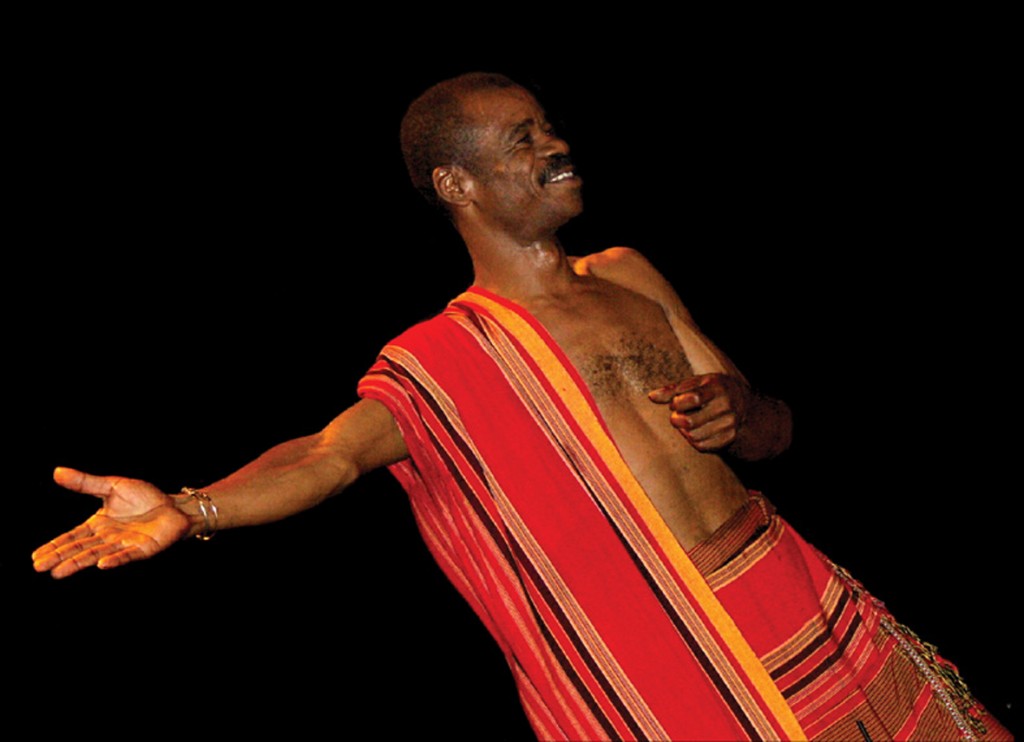

It’s lovely, yes. And she’s chosen great artists to work with. I mean, Jaojoby is spectacular.

Yes. He’s somebody it would be great to see more of.

Yes. Indeed. Anything else we should talk about?

Well, I think we should mention that Madagascar has been very challenged politically of late. That’s had severe consequences, and not just the obvious ones. I mean, during the stretch of time when the presidency was contested [2009-2013], the economic decline was sharp and horrible. Madagascar was a place that was on the rise. Things were looking up. The infrastructure was improving. Job possibilities were improving. Health care was improving. And that all just seemed to go out the window. And that’s heartbreaking. To have a sense of hope, and then to just have it pulled out from under you… And it was pulled out. What happened inside Madagascar was bad; there were bad decisions. But Madagascar is able to exist, in many ways, based on the terms of other countries and multilateral organizations that have a lot more power and resources than they have. So with this period of political unrest, when so many governments and aid organizations pulled their aid, pulled their economic agreements—you know, that had a huge effect.

There was a trade system that had been set up that allowed for textile manufacturing and garment exporting, things like that. Whether or not those factories were great things for the workers, that’s something that could certainly be debated. But it was there, and then it was gone. Jobs were gone. And there’s another wave of internal migration that’s been part of that. People had moved to cities and towns to get these jobs, and then they moved back to the countryside to work on the farms again, so there were a lot of communities in…disarray is a strong word for it, but at least in some state of unrest. Even under the more stable political leadership of the early 2000s, decisions were being made about how to deal with Madagascar’s resources—titanium, oil potentially, sapphires. The influence of large international corporations in Madagascar has certainly grown, and it seems that Malagasy people are pretty voiceless in this. They’ve not had a lot of say in what’s being done by mining companies—Rio Tinto, the Australian/British conglomerate, being one of them.

And again, these are not easy things to figure out. You wouldn’t want to close the borders. Madagascar tried that--that was not a good idea of a way to run a country and run an economy, and there’ve been some good faith efforts to tie some of these mining activities to some conservation activities, but much of that is discussion that’s happening at levels that are not really involving local people in the discussions. Land that used to be considered the people’s land, or the government’s land, is now being leased out for either agricultural purposes or mining purposes. I think it’s kind of the next thing to watch in terms of what’s going to be happening economically, politically and ecologically also.

That’s good stuff to have in my head when I’m there.

Oh yeah. When you’re going to the south, you’re going to see a lot of the mining stuff. And I will say, you know, from what I hear: Be careful. It’s not the place it used to be.

It was dangerous even when we were there 13 years ago and I know it’s worse now.

From what I was hearing at a recent conference at the University of Toronto, it’s become much more weaponized. The stakes have gotten higher and people are more desperate. The mining story is also affecting the flows of people. Think about the cultural practices of people. In a community, there might be a whole set of taboos that everyone in the village had to follow. You know, nobody farms rice on Tuesdays and nobody walks across that field over there eating sugar cane. You know, these were just the rules. Everybody knew them and it created community cohesion and some fear, as well. But those sorts of things are harder and harder to maintain. The sorts of ways that people keep each other accountable and feel responsibility for each other, as more and more strangers are moving in and as community sizes expand, it’s harder to have those kinds of relationships. So you do hear anxiety about these new operations, these new economic opportunities and all of this migration and unknown people coming in. Of course this is a global story. You know, we’ve had this in the United States. This is North Dakota today, right? It’s not specific.

A global story, yes, but it’s poignant here because these cultures had survived quite well until pretty recently, right?

Well, it depends on who you ask, but yeah, for many of them, they’ve done quite well. Just the sheer numbers of people on the island have increased a lot. The population has doubled since I first started working in Madagascar in the early ‘90s. I mean the number you’d have in your head was like 11 million or 13 million, something like that. Now it’s 22 million, 22, 23. Every society has dealt with population increase, so there’s no reason to think Madagascar can’t do that too. But they do have a lot of things happening very quickly that they’re not able to determine for themselves, at least at the local level. The pace is kind of out of sync with the ways that culture and social organization can keep up with that change.

And, as if all that were not enough, Madagascar is experiencing more and more severe weather patterns too, isn’t it?

You know, every few years there is a story in the news about a devastating cyclone, a tropical hurricane that has hit some region of Madagascar. And when this happens, infrastructure that the community, or maybe the European Union or the Malagasy government, has spent three years building—replacing bridges, shoring up roads—it’s just gone. It’s gone in a day. Whole villages are wiped out. Actually, communities are fairly quick to rebuild. One of the good things about the kind of housing that many Malagasy people live in in rural areas is that it is fairly easy to rebuild. In some ways I think it was built with the idea that it was going to fall apart or it would need repairs and they could get the supplies from nearby forests. So it’s not so much the housing, but the whole rice harvest for a year might be gone. Food insecurity in Madagascar is something that does need to be addressed. Food insecurity is a big deal partly because of these climate conditions. Irrigation systems are hard to maintain, things are unpredictable, and it’s not easy to store rice. If you store it in the same place where the cyclone hits then all your stored rice is gone. And so the nature of their agricultural economy really makes them quite vulnerable to these weather events that are happening more and more frequently.

It’s been a couple of years now since there’s been a really bad one, but at times they come through in waves. They don’t get a lot of coverage. When something happens in Madagascar the rest of the world—at least the North American world—doesn’t hear very much about it. They’ve also had problems with locust plagues and with the cotton fields and the corn and sometimes drought. Microclimates of Madagascar are also interesting to think about, because you could be having a cyclone in the north and a drought in the south. These things come together to create some really terrible conditions for the people who live there.

Wow. Not an easy state of affairs. Thank you so much for all the insight and information.

Thank you for this opportunity. It was actually a lot of fun.