Grateful Dead drummer percussionist Mickey Hart has pursued a long career as an avid recorder of world music—and more. Starting in the late ‘60s, he began making state-of-the-art recordings of everything from classical Indian music to Koranic recitation to West African drumming, powwows and the multiphonic chanting of Tibetan months. Hart is now in the process of turning over his audio archives to Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, which has just released the 25-volume Mickey Hart Collection, drawn from releases that first appeared between 1988-2002, distributed by Rykodisc. For more on the recordings, and to download titles from these 25 volumes at mickeyhart.net. In October, 2011, Afropop’s Banning Eyre spoke with Hart about the collection and his life in recording.

Mickey Hart: Banning, how are you?

Banning Eyre: Busy, but happy.

M.H.: One of the things is to be happy you have to be creative, and to be creative, that makes you happy.

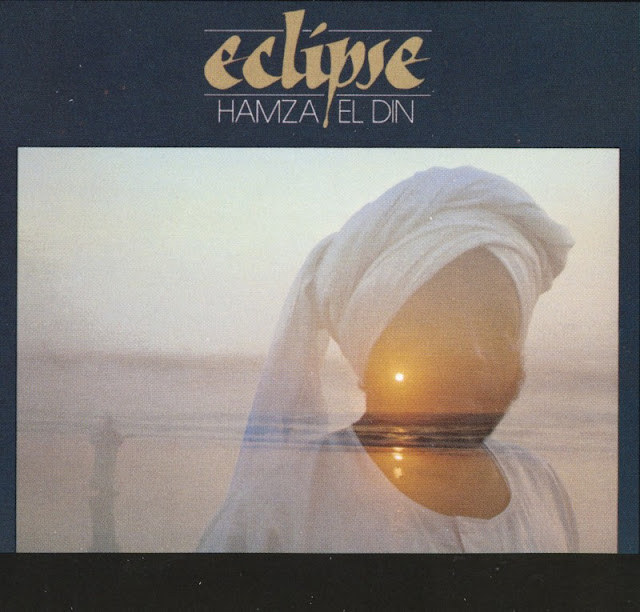

B.E.: I spent a good part of the summer in Egypt, and I thought of you because we were exploring a lot of Nubian music, and one of the real touchstones for me in discovering Nubian music is your Hamza El Din Eclipse record, which is still one of my favorite things to listen to at night.

M.H.: You are absolutely right. It's the soft side. Hamza had a real touch. He was the desert. And you know, when I went with him to Komombo, to Nubia, I brought my tar there—the single membrane drum. It was just filled with the most amazing harmonics, things that you never hear normally when you play the instrument. I had to play it in the desert. I had never heard the drum sound like that. It was so intimate. It was like a part of me. It was going back to its birthplace, you know. That really was an ear opener.

B.E.: Well, we miss Hamza. But Nubia remains. We didn't get all that much into the remote areas, but we found some great Nubian music in Cairo. And it's interesting in the context of the revolution. Traditional music is finding new homes in the city. There's a bit of a resurgence of a cultural Revolution going on, because a lot of traditional music has been traditionally marginalized there.

M.H.: Yeah, yeah. I know that a lot of the Bedouin music is being practiced now in the cities. The nomadic music has come to the city. That's what I've heard, anyway. That there's something of resurgence now. They're picking up on it. Picking up on the power of desert music. That's really gratifying. Because I always loved that music.

B.E.: I think that's true. That music has some real champions now. There is a new cultural centers one called Makan, and another called El Mastaba. Zakaria Ibrahim from Port Said has El Mastaba, and he has a stable of acts, including an excellent Bedouin band. It's making the music more accessible to urbanites, and also international visitors. So that's exciting, kind of a cultural subtext to the political revolution.

M.H.: It's all part of it. Those kinds of music have a purity to them that resonates. There seems to be a need. You know how music is. It has to serve a purpose in order for it to be viable. That was all about freedom, self-expression, all about celebrating the joys and lamenting the sorrows, all the real things of life, as opposed to manufactured music, which is derivative.

B.E.: Yes. And Egyptian pop music has been in something of a doldrums for a while now.

M.H.: Well, perhaps they didn't know how to deal with the electric thing.

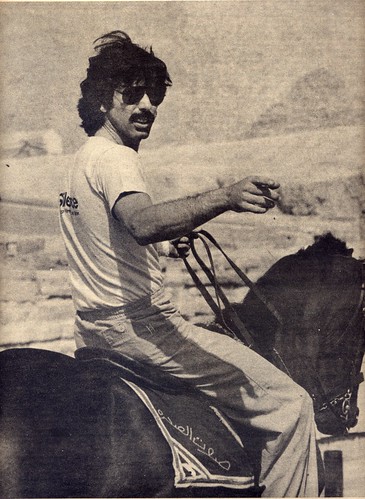

Grateful Dead Play at the Pyramids of Giza 1978 (photos courtesy of ukrockfestivals.com)

B.E.: Yeah, plus they've concentrated on a lot of very sappy love songs and the industry is largely controlled by big business interests, some from the Gulf. It's not very creative.

M.H.: Totally superficial. And that's why this older music is so important, indigenous music in general. There's a certain kind of resurgence, in a way. They're not necessarily practicing the old forms, but there are parts of the old forms that they are practicing. Like in Indonesia they call it kreasi baru, using the old gamelan, you know, slonding, the old iron gamelan, but with new composers composing on the ancient instruments.

B.E.: Oh, I love that.

M.H.: Slonding, they call it, the iron gamelan that had faded out. Well, no, not faded out, it was ripped away from them by the war. When I found the Fahnestock music, I just fell in love with slonding, and all the iron gamelan music. Then when the music made it way back into their culture, I went there to record The Bali Sessions...

B.E.: Which are amazing.

M.H.: Yeah, that's about as good as it gets. And I asked Pak Dibia, "Please give me your five greatest recordings.” Pak Dibia is the ethnomusicologist at the Institute of Music in Denpasar. One of the recordings he gave me was Music of the Gods. My heart was beating out of my chest. He gave me back the music that I had curated at the LOC from his culture. Oh, my God!

B.E.: Oh, I remember that story. That's wonderful.

M.H.: It just came full circle. But at the time he didn't know it was mine. I just looked at him and thought, "Should I say something?" My heart was pounding. I had a big lump in my throat. I told him, “This is one of my recordings from the endangered music series at the LOC. I did this for the Library of Congress.” And he just grabbed me, he hugged me, brought me in like a family member. I was no more like a visitor anymore. I felt like I was one of them, because I had given back, repatriated their precious music. This was one of their long-lost cultural treasures. The music goes back, and then the next generation picks up on it and takes it a step further, and then they take the essence from it that they lost, the music dreams are important and serve a purpose in their lives.

B.E.: That's incredibly moving to feel like it's making a difference back at the source.

M.H.: That was really one of the moments.

B.E.: So let's back up a bit. Tell me exactly what's happening with the Smithsonian. You're giving them these 25 sessions. But I understand there's a lot more in your archive. So give me a sense of what exactly you're turning over to the Smithsonian at this point.

M.H.: I wanted all my remote recordings to live in one place. You know what I mean? They're all finding a good home. And I want it preserved forever. You know, record companies’ come and go. I don't want a record company. Smithsonian Folkways will be there for a long long time. Folkways was the collection that piqued my interest years ago in the world's music. When I heard the Mbuti Pygmies. That was what started me out when I was a kid. Moe Asch then gave the collection to the Smithsonian. Back in the 1980’s I was called in by Anthony Seeger, to clean it up, to take the pops and clicks out using a signal processor called sonic solutions that we had in our studio. So this is like full circle. Then Howard Cohen my co-manager mentioned that I should do something with the collection, because it was out of print. Rykodisc had gone out of business. I thought, "Hey, the artists are not getting paid now. It's out of print. You’ve got a search around for it." I was now on the board of Smithsonian/Folkways again, and it just made sense. So I thought, “Perfect.”

So this is the first 25. If this release goes well, which I'm sure it will, I'll open up the rest of the collection. I've got hundreds of recordings in the vault from around the world.

B.E.: You have lots of stuff that has never been released.

M.H.: Oh yeah. And, you know, this is the place for it, because they're treating it the way I would treat it. First class. If you want a hard copy you can get it, if you want a download you can it as well. I'm sitting here in front of me with my hard copies. It's beautiful.

B.E.: I remember the old packages. They were beautiful.

M.H.: These are clean. They aren't multi-colored things like the reek releases, but they don't have to be. It's like sepia. It's lovely. It's just elegant. They all look like they are a matched set, and they are. They did a great job. I'm up there with the best songcatchers. Laura Bolton, Azevedo, Fahnstock, the lot of them. Think of it, Banning. These are the greatest song catchers in the world. All of these amazing heroes and heroines that have circumnavigated the world to bring this music back. It's not just about the music, it’s also about the amazing stories how that music was recorded, and all the incredibly dangerous, vile conditions that they had to endure to bring the music back. I mean, in a tropical rain forest, in the desert. Imagine recording with a Presto Disc-cutter in the rain forest! Unbelievable.

B.E.: I hear you. These people are heroes.

M.H.: Heroic! I mean, you're talking about Marco Polo types. Facing disease, loneliness, the elements, and bandits. And hauling the gear out on schooners, on donkeys, and having to take all those acetates, all the wire, all the wax. You know, with every form of recording material, there is a problem. When you take it out of the studio, into the field, then you become a real artist. It's the dogs barking. It's the insects biting. There's the rain, the humidity, the heat, the cold. You name it. Everything is the enemy. You know, to be amongst them... [LAUGHS] Wow! So, there's a lot. And also, these artists will get their royalties back. The monies go primarily back to the cultures that spawned them.

B.E.: That's tricky. How do you figure out who to give the money to all these years later?

M.H.: Right. When you're a nomad, well, I can't find the nomads. So what I did was, whatever they asked to get paid for their performance, I would double it. That was my rule. They would discuss the fee amongst themselves for a while and then come back with a fair fee. I knew I would never see them again so I double it, wherever it was.

B.E.: That's great. Probably also a way to guarantee a good recording. You establish good will.

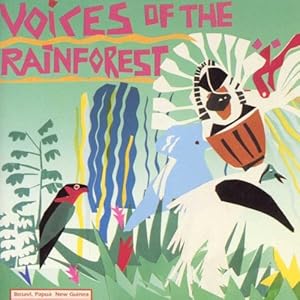

M.H.: If there's no way to get the money back to them for instance you offer to put light bulbs in the Cairo Museum, or something creative. Hamza gave the money from Egypt to a drum school near Aswan. Or, with Steven Feld, all that money for Voices of the Rain Forest went back to the Kaluli and to also to their music programs in their community. We also have sent books and cds to their libraries, That's how we do it.

B.E.: That's very smart.

M.H.: It's very cool. I never wanted to be a pirate. This was supposed to set the pace for future recordists.

B.E.: And like you just said, you really have to work not to be a pirate. Especially with old recordings. Because if the artist is dead, even if you go back to the village where the guy lived, there's no telling that the person whose hands you put that money in is good to do the right thing with it.

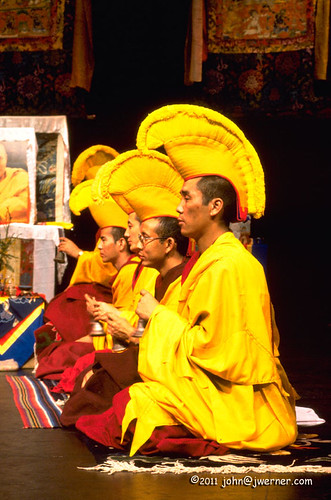

M.H.: If you can find the actual artist, that's one thing. If you can't, you try to do some good with it in the culture. That's a real hassle sometimes, but that's all part of this. I really wanted to set the pace with this. I really wanted to make this as an example for all recorders in the future, that they don't copyright the music in their name like many of the old timers did, to honor these traditions, and release these voices. For instance, anyone who wants to work on a project for the Gyuto Monks, it's for no fee. If they don't give their services for free, then they just don't work on the project. Expenses yes, but making big money off the monks, no way.

B.E.: And Smithsonian is down with that.

M.H.: Yes. I just made it very simple. If you want to make more than your expenses, and a standard rate for doing the business then this project is not for you. So it was very simple. That was a way of weeding out anybody who wanted to be a profiteer, or to monetize the music. The cds were never meant to make money other than for the monks and their rightful ownership and royalties go to them. So those were the reasons I wanted to put the collection back into circulation. The Smithsonian agreed to take care of all of the royalties, and that was another thing. In the past I had to maintain all of the records, and that is a serious burden.

One of the things that Moe always did, even if it was tree frogs, was he always had one copy available of everything, all 2600 of them. That's one of the things that made Moe so amazing. Even if it was tree frogs which no don’t was not a best seller, there would be at least one copy in print. His whole catalog was always in print. That's one of the reasons that Moe gave it to the Smithsonian. The Smithsonian agreed to keep it all in circulation, every last one of them.

B.E.: Beautiful. Of course, now with digital technology, that's much more doable.

M.H.: Yes, and that's another reason I gave the music to the Smithsonian, because they agreed with me and of course with Moe Asch, who I modeled this after. Moe was a big hero of mine. Everything has to be in circulation, even if it only sells one copy a year. I must say to see the whole body of work in front of me is very impressive. I am personally taken aback by the scope of it all. I've never seen them all in one place. It’s really beautiful, and there's a lot more behind this. Like with the Bali recordings. I released three CDs, but I've got 12 more hours behind those three CDs that could come out someday. This is just the beginning, and if everything works well, and people appreciate it, and Smithsonian Folkways do what they say they will do, then I'll start opening the rest of the vault up, and let these voices be heard.

B.E.: That is exciting.

M.H.: Yes, it's really exciting.

B.E.: So let me take you back to the beginning for a moment. I'm curious to know how this all started. I understand that hearing the pygmies was a real inspiration for you. And then later, all these great world artists started turning up in San Francisco. But how did you get the bug to start actually recording them yourself. What was your ah-hah moment for that as a personal endeavor?

M.H.: Well, Owsley was a major inspiration. Because Owsley... You know whom I'm talking about?

B.E.: Yes I do. [Stanley Owsley, Bay-Area, 1960s counter-culture figure who designed the Grateful Dead sound system, among other distinctions.]

M.H.: Yes. You know, when he first started recording the Grateful Dead on the mono Nagra, he was recording at the highest possible quality in the field. But what he was really doing was creating a sonic notebook. He was just trying to prove his theories, his microphone placement technique and how the band sounded using his soundscape theories. I would have long talks with him; he started describing sound like it was a landscape. He was calling it a soundscape, which we know more of now from Murray Schafer’s book. I began to notice there was so much wild sound in the world, sound that could not easily be fit in a studio situation.

B.E.: You guys did all right in the studio on a few occasions; I'd have to say.

M.H.: Right. But its strength was in the moment. Not to degrade the studio records. But the recordings never really lived up to the magic that you could make on stage. It was a beast that could not be totally caged.

B.E.: Sure. There was a particular thing that happened on stage that was never going to happen in a studio.

M.H.: That became a real challenge. Also, the noise of the world and all the sound that was so attractive to me lived outside the confines of a controlled situation like a studio. I think the first thing that happened was Weir and I... Weir, I have to give him a bit of credit here. One day in ‘67, he said "Let's go to the zoo and record the animals, it’s a full moon." You know, we had just taken some acid and it sounded like a brilliant idea at the time.

I went over to Owsley's house, and he gave me his mono Nagra. I had never recorded before, and just thinking back on it for Owsley to have given me that mono Nagra, he must've felt something. It must have been an act of faith or something. I can't even imagine him doing this. He gave it to me. And he gave me 40 feet of mic line for a 2-foot job. That was the thing. "Okay, here's the mic and all I have is like 40 feet of mic line." So he plugged it in, he put some tape on the nagra, showed me the meters and then said, "Okay, all you got to do is put it in record, and don't let the needles go into the red. Keep it between here and there, and just point it at what you want record." I walked out the door, got Bobby, and we went out to the zoo, and we started climbing the gates. And we were laughing so hard; the mic line got caught on the top of the gates of the zoo and impaled me.

B.E.: Really!?

M.H.: So we were there laughing trying to climb the gate, and the guards came. And, of course, they escorted us unceremoniously out of the zoo. I had just landed on the other side of the gate when the guards came running up with their flashlights. And sure enough, the animals were completely silent anyway. So much for my first recording experience.

B.E.: But did you record the guards?

M.H.: No! We didn't have time to get it in record!

B.E.: Oh dear.

M.H.: I mean, it was one of the few times I've failed to record something in the field. But that moment really tweaked my interest. The idea of how hard it was to get into the zoo to record. I mean, that was like the beginning of it all. So then, as you said before, all of a sudden, here's Ali Akbar Khan, and I'm taking lessons from Allah Rahka, and then all of a sudden, there's Sultan Khan and then Zakir Hussein. And Ravi Shankar, and all of these great maestro musicians. And you see, there was no PA for them to use then. There was nobody with a PA. They couldn't afford a PA, and they were playing just acoustically. And they only played in living rooms, homes that people would invite them over for dinner and a small concert. They couldn't play large concerts, you couldn't hear it. So I went over and asked Owsley for some speakers. Dan Healey was a very important player in these early days. He was a real engineer and knew how to make this happen. I watched and studied his technique. He was my teacher and fellow traveler back then, he made these early recording happen. This was before Alembic. It was a Heil driver and a 15-inch JBL in a custom box “the bear” built. Oh yes, and we took two Mac 75 amps, two microphones, and a little board. We made a nice little PA for them. Then we started doing the PAs for these small gatherings, you know, living rooms and so forth. It was a tiny little PA, and then it got a little bigger.

The deal was we were running Nagra master curve, recording at 15 inches per second. No one was running at 15 in./s recording “third world music”. I mean that was just a waste of tape they all thought. This was before the Nagra’s had big reel extenders.

B.E.: So, how much time would you get on a reel?

M.H.: I think I got about 22 minutes. Way too short.

B.E.: Especially for Indian music.

M.H.: Oh, no, no, no. It had gaps in it, and all that stuff, until I found another mono Nagra. And then I was doing the leapfrog thing with the Nagras. The deal was... "Look, all I want to do is hear this incredible music in my studio, in the barn on great speakers." I used to love to drink cognac, back in those days. Smoke a joint, a little cognac, sit back, and listen to the world's greatest music ever on the master tape at 15 in./s. That was happiness. That was the world. So I said, " I will give you a copy of the performance. If you want to do business with it, do business. Sell it, whatever you want to do. All I want to do is listen to it in the privacy of my home." I always listened to it alone, I didn't want to be distracted. We will supply the PA. It was an offer they couldn't refuse. They get the best recording that could be made of their music to do whatever they wanted to do with it. If they wanted to make a proper recording I would provide the original master. I knew the master would be safe and well cared for in my vault.

B.E.: Right, at that time the audience here was pretty undeveloped.

M.H.: And I got to listen to the Nagra master curve. So this was the great treasure. It was like finding gold.

B.E.: Is that how the Hamza El Din record, Eclipse, was made?

M.H.: No, that was a multi track recording. That came later. That was in the studio. That was when I got the first 16 track MM1000. The musical trade winds just blew the right to my doorstep, and here I was sitting in front of the greatest music that I had ever heard, and it was going unrecorded. Sometimes I'd make a cassette of the music for a friend, or give it as a gift to someone who was having a baby, or getting married. And more often than not, the cassette would be there on the kitchen table when they left. You know, I couldn't even give it away.

But it was a treasure. So that’s how it started. And then, Don Rose and Arthur Mann, who headed up Rykodisc, came into the picture. They started up this CD-only company. CDs were less than 1% of the market at the time. They called it RYKO DISC.

B.E.: I remember that. You were one of the first things they put out. I just started writing just at the time, the dawn of CDs.

M.H.: Yeah, Yeah. So I saw this little ad in a billboard magazine. CDs ONLY. Don Rose left me a message on my answering machine. He had heard a cassette of The Diga Rhythm Band recording. That's how it started. He had heard a live Diga recording. But anyway, he called me and then he said, "Look, I really would like to put out this music that you are recording. What do you want?” I said, "I'll call you back. Let me think about it." And then I sort of went to the mountaintop. What do I want?

B.E.: That gets your attention.

M.H.: He said he wanted to put out my recordings. He didn't go so far as to say he was going to finance everything I anted to do, but that’s what I wanted really. I wanted a home for all my work, whatever it was. So I took a walk, and a day or two later I called him back. I thought I’d take my best shot. I thought his guy is out of his mind, you know, crazy. The president of a company that sells only cds? This was when you couldn't find CDs anywhere. I liked him right away. This guy is on the edge. So I said, "Okay, here it is. I want a home for all these recordings. Whatever I do, I would like you to release it. And I want you to treat it like we would treat a Grateful Dead record. Package it first class." Bill Graham always said to me, "If you put a diamond in a brown paper bag, people won't understand its value. They won't think it's valuable. If you put a diamond in a really nice case, people can see not only the worth of the stone, the beauty of the stone, but they know that the way you presented it was first class, it has great value." It's like the music was a diamond. So I always remembered that. And I took that forward.

And Don said, "I'll do better than that. Not only will I release everything you do, but I will pay for it." In those days, it was my dime, you know. Whatever it costs to bring equipment there and back. It wasn't much. I owned the equipment, and Owsley gave me the machine. That was before I bought my own. It was nothing really. And this guy made me this offer I couldn't refuse. I said to him... I wanted to see if he was real. So I said, "Okay, I want to record the Koran and the Torah, the Talmud. I want to record a 14 CD set, 2 14 CD sets, one of the Koran and one of the Talmud." And he said, "Okay, you got it." I had thought I was throwing this guy a hard ball and I wanted to see if he would choke. And so whatever I did, whether it is Music to be Born By, the heartbeat of my son, or Hamza, or the monks, or Olatunji, or Indonesian music, he was there. Not only that, he did it with a smile. And packaged it as well as it could be done.

B.E.: I have those originals. They're really nice.

M.H.: Yeah, they're beautiful. So that's how it started. I have to give the credit to Don and Arthur, and their great vision. The thing about an artist, one of the things that many people forget, is that artists create. And many times an artist will create, create, create but never be able to publish, for one reason or another, because he doesn't have an outlet. So then you get artistically constipated, and you stop creating because you can't share it with the world. So they were offering me something very valuable, an outlet to the world, and also giving back to these cultures. I have to say, turning Jerry on to the monks was the biggest thing. When I heard the monks I thought, "Oh, wait until Garcia hears this." He was a true lover of sound. I beat it on home back from Amherst College when I heard them. And said, "Jerry, you're not going to believe this. It's one monk, he sings three notes simultaneously with the low note at 70 cycles." He goes, "You got to be kidding." And I said, "No, I'm gonna bring them out here to Berkeley Community Theater, and we're going to sponsor them, take them around the world, and support them in exile." And he goes, "Cool!" And so that’s how all the tours of the monks got started.

(Hamza El Din with Hart)

B.E.: So that all happened during the Ryko period?

M.H.: Yes. The monks. That happened during the Ryko years. I got turned on to the monks by [Robert] Hunter, who had recorded a KPFA broadcast of Huston Smith's recording made in 1965. His recording of the Gyuto monks in exile in Dharamsala. Huston was over there to study the their religious rituals. He heard the monks one morning as he woke, and he realized then what he was there for, and brought it the choir’s amazing sound back to the USA, and in ‘67 he played it on KPFA. Hunter had a microphone in front of the speaker, recorded it and then he gave me that cassette. I listened to it for two years before I knew what it was. I listened to it almost every day, when I was coming down or just to relax. I would just deep listen to it. I had no idea what it was, until I saw Lewiston's 1970 recording of the monks, his stereo recording from Dharamsala. On the back of the LP, the story was all laid out. Chanting monks with the capacity of singing three notes simultaneously, a vocal miracle. And then I go, "Holy shit!" I called Hunter said, "You know what this is?" Hunter had just said, "You have really got to hear this." He just gave me the cassette unlabeled.

B.E.: He didn't know it was?

M.H.: No! Well, he might have. Hunter just happened to be there with another cassette machine, and an RE-15 at his house. For some reason he recorded it, and he just gave me that cassette. You know how those things used to be. In the middle of the night, someone would just give you something and then walk out of your life and never say another word about it. I didn't say anything to Hunter. And so I listened to it, and that's what put me on to the monks.

And then when I found out that Robert Thurman, Uma's dad, who's a Buddhist scholar, brought the monks in to the USA; I think it was in 1980. He was sponsoring the monks. And through Fred Lieberman, I found out that they were going to be there. And we were researching Drumming on the Edge. The grateful Dead were on tour. So Dan Healy and me went to Amherst College with the Nagra, which I always carried with me on the road. We had tea with them and recorded them at Amherst College. It was a puja, just a little sit down prayer. And I heard them for real, and I said, “Oh my god!”

They were just chanting in people’s homes. I said, "Oh no, no, no, no, no. Come to the West Coast. My friend has got to hear this." And so I held a press conference on the steps of Berkeley Community Theater. Joe Selvin was there. The press just looked at me like I was from another planet. “The tri-tone! Each monk has the ability to sing a chord!!” It went way over their heads. But we filled Berkeley Community Theater and wrote a check to them for $80,000 that very night. John Meyer [pioneer of sound reinforcement] was in on it, he supplied the sound system and we were off and running. We gave them the Grateful Dead board live mix, in the hall, and put them through a real sound system for the first time. And that was the beginning of our sponsorship of all of their tours over the years.

B.E.: Was that the CD you eventually released?

M.H.: No. I don't think we released that. That one I never released. That’s somewhere in the vault.

B.E.: I see. The CD came later.

M.H.: Yes, that one was done at Skywalker Sound.

B.E.: Okay, I think I remember this. That was a very high-tech recording, wasn't it?

M.H.: George Lucas and I came back from Joseph Campbell's funeral in Hawaii, and he was telling me about this big room he had built. And I said, "No way, George." You know, we're on the plane. "No, no, no. It's so big I don't know what to do with it." And I go, "Okay, George, I got to see this." So we went up to Skywalker, we walked in, and I saw this huge room. And I said to George, "Wow, You built this for me!" Then I called Tom Flye, my engineer, and said "Tom, (this is a like one in the morning.) "Tom, get up. Go get McCunes's, remote truck and bring it here at 10 o'clock in the morning. We must record the monks in this magnificent room.” George and I had gone from the airplane to the soundstage, you know. He had no machines, it was just a just a shell. But the monks were in town. It was the first time they were in town on tour. So that's when we recorded the CD.

So, one thing led to another. I got into recording indigenous music not only in the studio, but also in the field. And it became like a real adventure. You know, I don't vacation very well, Banning.

B.E.: I have that problem too. There's has be a reason to go somewhere, right? A project.

M.H.: Yeah. So when I go places, I've always got my remote unit with me. My wife figured it out about 20 years ago, so it's not as easy as it used to be. But we made a deal. She said, "Okay, here it is. No more of this recording on all our vacations. I'm not placing the microphones anymore. I'm not going to Thailand and Bali to be a mic slave anymore. What we'll do is for every six days of real good vacation, you can have 24 hours, one day of recording." I said, "You got it." So that was the deal, at least when I take her on vacations. We do six days of legitimate, happy vacationing. And then I get 24 hours. Seemed like a fair deal. So far it has worked just fine.

So when we spent three weeks in Bali, I had three 24-hour periods.

You know what we did on our honeymoon? We went to Hawaii, and I rented a little house on the water. I was recording the surf gently flowing on the beach. It was a beautiful, quiet little harbor. I had two microphones, U87 Neumanns running directly into the stereo Nagra. By this time I had reel extenders. We were rolling tape. We were on earphones, and we were making love, listening to the surf. We each had headphones on. And all of a sudden I could hear the surf getting closer and closer. "Okay! Time to move the microphones." We ran out to the beach to move the microphones another three or 4 feet in so the surf didn't get them. Back under the headphones, make love some more. We did this all night. This was our honeymoon. She should have gotten the idea that I was an addict recorder that night, but it was sooo romantic and it just was the right thing to do at the time.

B.E.: That's hardcore.

M.H.: Yeah. That's hardcore, you know what I mean? So you ask me how serious it is. It's a habit. It got to be a serious thing. Is there a rehab called Recordists Anonymous?

B.E.: There might be, an elite club.

M.H.: "I am a Recordist. My name is Mickey Hart. I am an addict."

B.E.: So are you still doing this? Do you have plans?

M.H.: Oh yes. My next plan is the Golden Gate Bridge. I'm sonifying the bridge. Also, I have been working in the cosmos, recording from radio telescopes, from the Big Bang 13.7 billion years ago, through many of the epic events of the universe. I am presenting this DVD at the Smithsonian IMAX Theater next year. I'm working on transferring light waves into sound waves. So you talk about remote recording? That's remote recording. What has happened is I've gone galactic, I've gone stellar, and I’ve gone cosmic. Now I'm working with these fundamental sounds of the universe. I have been doing this for 2 1/2 years.

But the next sub-lunar project I have is the Golden Gate Bridge's 75th anniversary, and I'm taking feeds off the seismic instruments, the accelerometers. I'm transferring them into our range of hearing and creating a symphony around the sounds of the Golden Gate Bridge. John Meyer will be doing the sound on shore, and celebrating the bridge. So the bridge will be singing its signature song. You know, it's a giant wind harp. We will be on the shore listening to its song and having a musical conversation with it…how cool.

B.E.: Okay, sure.

M.H.: I tried doing this in the 70s. I went out on the bridge in the middle of the night with my rubber hammer trying to excite the bridge and record the sounds with my Nagra. The first time they kicked me off, the second time they cuffed me.

B.E.: Really?

M.H.: Yes. They almost put me in jail in 1974. So I dropped it. And then this year I realized, it's the 75th anniversary of the bridge.

B.E.: Time to try again.

M.H.: You know, Mickey Hart, hippie madman recordist. Everything's changed quite a bit now. Now I have a little bit more cred, cachet, if you will. So, anyway, now we've gone past the bridge authority, and the Golden Gate Authority and are clear to go.

B.E.: Now, you are an honored guest. You wait long enough...

M.H.: Now, I'm an honored guest. That's the next major sound sculpture. The Golden Gate Bridge.

B.E.: That's fantastic. I want to take you back for a minute to the Egypt adventure, because we have Egypt on the brain these days having just returned from there. I know the Grateful Dead performed in Egypt. Was your recordings made around that concert?

M.H.: Yes, after we played, I spent about three weeks going up and down the Nile.

B.E.: What year was that?

M.H.: 78? 79? Something like that. I went up to Alexandria and recorded the Bedouins. Then I went down to Aswan. I recorded the café music, up and down the Nile, which I never released.

B.E.: Oh, I would love to hear that stuff.

M.H.: Me too. I haven't heard it since I recorded it. Then I went down to Aswan and recorded the Aswan boatmen. The band went home, and I packed my Nagra up and went into the desert. Three weeks. That was great. That was really a moment. Then Hamza took me to his village in the Sudan.

B.E.: You knew him by then.

M.H.: Yeah. It was so sweet. The Nubians were so soft, such beautiful people. They played drums. My kind of people. Many of them had rattles and drums and sang. This would be a good eternity. It could be a good destination.

B.E.: I hear you. I'm dying to get back there and get more into the hinterlands.

M.H.: No, I'm talking about Musical Heaven.

B.E.: Hamza's music is pretty close to that.

M.H.: Yeah, and here was a whole bunch of Hamzas. You know, what Hamza did is he dropped me off in his village. He went off to grieve for his dad who had died months before. He went with his mother out into the desert and they just cried to the memory of his father. He left me alone in the village. I'm sitting there, in the middle of the desert; there are no real roofs on the houses. Only about half of the houses have roofs, because there's no rain there, I don't speak a word. They are fanning me, feeding the dates, and the kids are coming around pointing, and laughing, just really happy and smiling. I could only take about 20 or 30 minutes of that. I went out, looked in my car and pulled out my tar and started playing. Everybody came out of his or her houses, and then they all started playing drums. The women had beads on and they were all shaking the beads, jumping up and down in perfect rhythm patterns and the men were playing drums. There were about 40 of us.

And then Hamza comes walking down with his mom; he had this look on his face, wide-eyed. His eyes were wide open. And he said, "There hasn't been music in this village all year because we've been in mourning for my dad. And it's really great that you brought the music back. Thank you so much." So this was a kind of spontaneous eruption of music. They had suppressed the music for all these months, it was time. Hamza never told me about any of this. He just plopped me down in a chair, gave me some water, and left with his mom.

I have recorded in the Arctic Circle, which I haven't released yet -- the Arctic tapes. When the Grateful Dead played in Anchorage, I peeled off to kotzebo. As a matter of fact, my remote team was all under 12 years old. I took Ramrod’s son, Kreutzman's kid, and my stepson, who were 12, nine, eight at the time. I bought them parkas, knives sunglasses and goggles.

(Mickey Hart and Bill Kreutzman 1969)

B.E.: Everything they would need...

M.H.: We flew up to the Arctic Circle with the Nagra and the mic stands, mic lines, tape, etc. That is when I deputized them, gave them the oath, you know, the MERT oath. [mobile engineering and recording team] "I will record more than I erase." I made up this code as we flew above the Circle. We went up there and stayed in igloos, then we recorded the Inuit. Whenever the Grateful Dead went someplace I broke away from the pack and recorded something interesting, like with Tom Vennum. We were playing up there in Wisconsin, and there was the powwow and that recording became Honor the Earth.

B.E.: I remember that recording.

M.H.: I went to the powwow with my son Taro. We rolled tape all day and all night. Then after that came the "American Warriors” cd. The war songs of Native Americans who fought for the USA in many of our wars. From World War 2 to Korea, to Desert Storm. Those were two amazing Native American recordings. One thing just led to another, Banning. A lot of it had to do with me being physically around the world with the Grateful Dead, and my desire to bring back this music at the highest resolution, the highest fidelity. Because, you know, there is nothing like a Nagra. It weighs a ton. It's built like a tank and made like a Swiss clock. Most people don't realize how difficult this all is. They think it's really romantic, and it is in a way. But you really have to love doing it.

B.E.: They don't realize what a heavy load is.

M.H.: Oh, you know how heavy a Nagra is. If you are out there in the field, you bring the Nagra into the bathroom with you. If you go into a bar, the Nagra is wrapped around your foot. You don't leave it in the hotel. Without your machine, you are nothing. It's always around my feet, around my shoulders. Batteries! You know how many batteries there are in a Nagra? How much the gear weighs. Oh! You know what I mean.

B.E.: I must say, I do appreciate how light and small the current digital gear is. It may not have the romance of the Nagra, but it sure makes things easier in the field.

M.H.: I wouldn't take the Nagra out into the rain forest now. I would use a digital machine. But the other thing is, the Nagra will play in the Artic, and it will play in the rain forest. That's the other good thing about it. Bernie Krause [of Wild Sanctuary] and I, we tell Nagra stories. Of course, Bernie, he exaggerates sometimes. You know, like, "I found a Nagra in a glacier once. All I had to do was replace the rubbers. "Come on, Bernie!" "I dropped the Nagra out of a helicopter at a 40 feet. And when we landed the helicopter, I put the Nagra into record and it worked." And I go, "Okay, Bernie. Yeah. Okay." You know what I mean? It is like a drinking club or something. We both have earned bragging rights about the Nagra.

B.E.: That's great.

M.H.: Yeah, you know, you fall in love with your machine. My machine sits proudly in a place of honor on my shelf to this day. I will never sell it, part with it. And it's still calibrated, and tweaked. If I need it, it's always there. It's always has a shell it in the chamber. Well that's not a good analogy.

B.E.: Well, I get your point. Thank you so much for sharing all this.

M.H.: Thank you. I really got energized talking about this stuff. I don't get to talk about this world very often.

B.E.: It's wonderful to hear all this. And we'll get it up on the web soon. I'm still up to my ears in Egypt transcriptions.

M.H.: How long did you stay?

B.E.: A month.

M.H.: That's great.

B.E.: And we were busy morning till night, a lot of music sessions, and a lot of interviews.

M.H.: What kind of machine did you use?

B.E.: Just a digital Marantz PMD660, and a Shure VP88 stereo mic, just a hand-held mic, but it does a great job.

M.H.: That's great. I've got a Sony.

B.E.: It's difficult when you've got singing and drums, to get the balance right with just one microphone. We were just two people. One of the best things we did was we went to a Sufi saint celebration in a small town. It's called a moulid. There's a singer, and a violinist, and a flute player, and three percussionists, and the melody instruments are playing through octave pedals into systems where there are like five or six separate power amps going to separate speakers around the town. Everything's slightly out of phase and you’re getting all these crazy effects. And we're up on this podium with a singer and the musicians, and there's this crowd of thousands around at night under all these lights, like Christmas lights, and they're just going into trance. It was completely ecstatic. And the singer was extraordinary, really one of the best singers I heard the whole time.

M.H.: You've got to turn me onto that.

B.E.: I will. If you go to afropop.org you'll find a short video of this. And more coming. We're going to do five programs up with this Egypt stuff.

M.H.: I might have you on my radio program. I'm going to do a few shows on Grateful Dead radio. Where are you living now?

B.E.: I live in Connecticut, but I'm often in Brooklyn, where we produce the show.

M.H.: Maybe I can bring it down to New York City.

B.E.: Perfect. I'm there a lot.

M.H.: Let's find a date. Because you're talking about great shit here.

B.E.: It is rich. Very interesting.

M.H.: I will mention this to Howard. We do a retrospective on the Egyptian soundscape. Let's do it, because Egypt is really in the news. The Arab Spring! Let's do this.

B.E.: I’m game. Thank you so much, Mickey.

M.H.: Thank you, Banning. It's great talking with you.