Simon Rentner recently spoke with MIT Professor of Music Patricia Tang for his Hip Deep program MBALAX FEVER. They spoke about sabar drumming, Griot traditions, Senegalese independence and its influence on mbalax, Youssou N'Dour, Orchestra Baobab and more. Here is their conversation...

Simon Rentner: I'm Simon Rentner and I am here with Patricia Tang. She wrote the book Masters of the Sabar: Wolof Griot Percussionists of Senegal and we are here to talk about Mbalax.

First of all Patricia, why are you so fascinated with Senegalese music?

Patricia Tang: I think that Senegalese music is one of the best types of music in the world. I know that's a biased opinion, but I fell in love with Senegalese music when I first heard the music of Youssou N'Dour, who is, as you know, the most famous singer of mbalax music. I had seen him in concert many, many years ago when he came to Boston. There was something about the music, both the vocal styles as well as the percussion, that really intrigued me. And I kind of filed it in the back of my head. When I went to graduate school and I was thinking about my research, and what I might be interested in, I remembered the Senegalese music and I thought about Youssou N'Dour and I thought I wanted to do research on Senegalese singers. And so that's when I went to Senegal to do field work and became very interested in the music there.

Basically, mbalax is a very high-energy type of music and it's extremely danceable. It's very catchy. There is something about it that makes me want to listen to it all the time. I think I've told you before that I really could just listen to mbalax all the time. There is something really wonderful about the music, and the fact that it's percussion-based, I think makes it so interesting.

S.R: You're coming from playing in traditions that are vastly different from African improvisational music.

P.T: Yes, I've played violin, played classical music from a young age. And I think part of what got me really interested in African music was when I joined a Ghanaian drumming ensemble in my undergraduate years at Brown. It was the first time I ever played music that was not read from a sheet of paper, that was learned completely by ear and that was rhythmically extremely challenging to me. There was something about that challenge that made me want to know more about this music. I think that happens with a lot of people who get interested in African drumming, although Ghanaian drumming is the first type of drumming that I became interested in.

When I went to Senegal, I discovered the sabar, which is pretty much everywhere. You can't avoid sabar. You hear it on the street, in the neighborhoods and you hear it in the popular music. It's sort of all around you and because I had this interest in drumming, I got really fascinated by the sabar and wanted to learn more about the sabar drum.

S.R: How do you look at the sabar comparatively to other dense and technically complicated drumming music from around the world, whether it be tabla players in India or other drumming traditions in Africa? What is distinctive about sabar drumming?

P.T: Sabar is unique and distinctive in that it can be found only in Senegal and the Gambia. It is very specific to the Wolof people. It's a drum that's played with one hand and one stick, whereas many other types of drumming are done with two hands or with two sticks. The sabar has a very wide range of notes, from low bass notes to very high-pitched piercing notes. Part of that is due to the combination of the hand and the stick that allows the drum to make a lot more different sounds. I think what is also interesting about sabar is the fact that it's not just the complex rhythms, the polyrhythms of the different parts coming together, but it's also the long compositions, which are known as bakks.

Bakks are like musical phrases and they are phrases that are played on the sabar drum. Some of them are quite short, maybe lasting several bars or phrases. Others can go on for many minutes and be almost comparable to a symphony concerto. They are extremely virtuosic. These are compositions that are long. It's quite different from what I've found in other types of African drumming traditions.

S.R: So think about a bakk, especially a really elaborate, perhaps precomposed bakk, none of it is written down, it is all learned by ear. So what was the longest bakk you've ever experienced?

P.T: I guess I would think of it in terms of the length of time that it's played. There is one bakk that was composed by the Mbaye Family Drummers—the drum troupe that I worked with. This is a bakk that they call the "Bakk de Spectacle" or the "Spectacle Bakk." It's their virtuosic bakk that they play, that no other family can play. This lasts about maybe four to five minutes long. I transcribed it in my book and it goes on for many pages if you try to put it into Western notation. But it lasts for four or five minutes and it's very complex. It took me several months to try to learn it on my own. Well, I mean to learn it in drumming lessons. Apparently many of the drummers in the ensemble could play it after the second or third hearing, which is pretty impressive.

S.R: Wow, they could learn the whole thing just by hearing it a few times?

P.T: That's how the story goes. It was said that Lamine Touré heard it. He heard it and then he was able to play it by the second try. You can ask him about it later.

S.R: But that's insane. What is that? Do you think Senegalese Griot percussionists have a more developed or evolved sense in that way, of learning music aurally? I can't understand how, unless you are a prodigy, how one could do that?

P.T: My understanding of how the brain and the memory of Griot drummers work is that after they've been playing for many years there starts to be a certain repertoire, almost like a dictionary of shorter phrases that they are all very familiar with. I think what happens is after a while, when we might hear this bakk, or this long drum composition and not understand it and hear that it's very complex and find that it's just so complex we don't even know what's going on. For them, they probably already understand the different parts of it and they are able to perhaps parse it into different segments. By doing that I think that probably helps them to retain it and to memorize it. So that's my understanding of how they are able to retain and learn so quickly these extremely long and complicated bakks.

S.R: So the bakk from the Mbaye Family - what makes it distinctly Mbaye? Is there something in the sound, in the quality of the performance, in a phrase that signifies in some abstract way that this is Mbaye?

P.T: That's a very good question, which is a bit difficult to answer because a lot of it has to do with the nuances in each family's playing. It's something that you can put your finger on after you listen for a long time to the music of the three main families of Griots. I think what's special about this bakk, part of it, is that one half of the bakk is actually something that was passed down within the family from the ancestors and it had actually been based on spoken word. Since then, the spoken word has actually been lost but the bakk itself has been passed down. Other members of the family have added on to it and each of them have contributed some of their own unique flavor and style. I think that's what really makes this bakk special to the Mbaye family. If you asked them, they would probably say that it's more virtuosic and more complicated and better and cooler than the other families' bakks. But that's where some of the family rivalry comes in.

S.R: Is there a section during this three or four or five minutes that you think is particularly spectacular, or was really hard for you to play?

P.T: I think the whole thing is pretty difficult. There are some parts where it doesn't seem to stay in a particular tempo or time and I find that to be a little bit complex. But the whole thing is quite complex.

S.R: Does it stay in the time, or drop the beat?

P.T: It does actually drop the beat at one part. But most of it is within the time, although the untrained ear may not realize it.

S.R: So when it does drop the beat, is that a big deal? Is that something that happens normally? I'm just curious. Is that common?

P.T: It's not as common. What happens is when you have an entire sabar ensemble playing together, the whole ensemble has to be watching the leader and following them. The leader acts as a lead drummer but also as a conductor of sorts. So it means that everyone has to be watching the leader and playing together with him.

S.R: OK, so quickly, tell me how many drums there are in a traditional sabar outfit, and describe what the purpose in the sound of that drum is.

P.T: A typical sabar ensemble consists of maybe a dozen or so drums. It really can vary and it depends on the occasion for which they are playing. There is a lead drummer and if they are playing for a dance party or a dance event, which is most of the time, the leader plays a very tall drum called the Nder. The Nder is the leader. It's very tall and it has the widest range of notes of all of the sabar drums. If they are playing for an important occasion with a famous person such as the President, or if they are playing at a wrestling match, they will have a different drum, a bass drum called the Cól, which will serve as the leader. The Cól is actually one of the older drums. Perhaps that's why it's something that would be played for the kings long ago. So that's something that's still played for people of import and also in sports. The other parts - there is the Mbëng Mbëng. Mbëng Mbëng - you can guess where the name came from. It makes a sound that sounds like "bung bung". The Mbëng Mbëng is the medium sized sabar drum. That usually plays a part known as mbalax. Mbalax literally means accompaniment in the Wolof language. It has also come to mean the entire genre of Senegalese popular music that was made famous by Youssou N'Dour. So if you listen to this music, all mbalax music or maybe about 90% of this music has this accompaniment part played on the Mbëng Mbëng drum. That's called the mbalax part. Then you have the bass drums, which can play other accompaniment parts called the Talmbat and the Tulli. And you have a very small drum, which is called the Tungune. Tungune actually means midget or short person. The Tungune is a sabar drum that plays a different accompaniment. That's actually the most recent addition to the sabar ensemble. Actually I believe it just came about in the mid-1900's.

S.R: So take me back to 1960. What's going on?

P.T: 1960 was a big year in Senegal. It was the year during which they gained their independence from the French. As you can imagine, there were many celebrations happening in honor of independence. It was during this time that different people started forming dance bands that would become like a house band at different clubs. The first person to do this was a man by the name of Ibra Kasse. On August 3rd, 1960 he formed a band called the Star Band, which played at his club that was called Le Miami, or The Miami. This was one of the first mbalax bands, although maybe I shouldn't completely call it an mbalax band but it was one of the first Senegalese dance bands that came about during this independence era. The type of music that they played at this time was very much basically Afro-Cuban music, salsa music. This is a music that was all the rage at this time and had been the rage for several decades. In the 1930's several of the major recording companies started distributing a lot of records to Africa of Afro-Cuban music. Famous singles such as The Peanut Vendor were played. This music really was something that the Senegalese population really latched on to. It was the type of music that was being played in high society functions. So from about World War II onwards this was the music that everyone was listening to.

So in 1960 you have Ibra Kasse and he has his band, the Star Band. The Star Band starts out by mostly playing covers of this Latin music, this Afro-Cuban music. What they are doing is you have these Senegalese, who speak Wolof, their native language and perhaps French. But instead they're learning these songs, which are sung in Spanish and very often they aren't even aware of what it is that they are singing. But they would learn these songs by ear and listen to these recordings. They would basically play covers of this Latin music. This was something that people danced to, dances like the pachanga and the bolero and things like that. So this is a kind of music that was very popular in the early 1960's. To give a broader picture of what was happening in 1960, you have the first President, Léopold Sedar Senghor, because they gained independence. He was important for many reasons, not just for being the first President of Senegal. He was also an extremely important figure in the Négritude movement. This is a movement that began in the 1930's and it was founded by the likes of Senghor as well as the poet from Martinique by the name of Aimé Césaire. This was a time when people like Senghor and Césaire were studying in France. They met and they decided to start this Négritude movement. Négritude literally means "blackness" in French. What their philosophy was, was that blackness was something that one should have pride in. It was something that was against, at this time, the French Colonial movement. They felt that if they could have more pride in black culture, and in particular black arts and black literature, that this is something that would give them a more equal footing with the French colonial powers. At the time that they started this movement, I don't think they had really envisioned that independence would come one day, which it did end up doing. But Senghor, who was a very famous poet, was a very important figure in this whole Négritude movement. In conjunction with that, when he became the first President of Senegal in 1960, he became a really important factor in the promotion of African arts. At this time, around the time of independence, many African countries started forming national ballets, and this was a way of really celebrating their own African culture. The National Ballet of Senegal was founded in 1961. This was a ballet that would showcase the amazing music and choreography of many different ethnic groups within Senegal. They would tour and go to different parts of Africa and eventually to Europe and to North America as well. So this was all an important part of Senghor's idea of Négritude.

S.R: So, the timbales and the congas just weren't black enough?

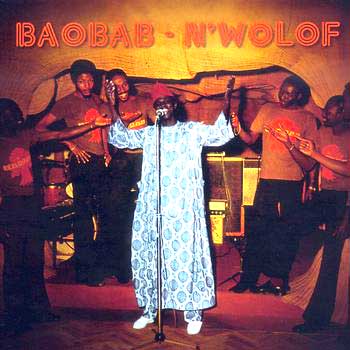

P.T: That's a very good question. The timbales and the congas were part of the original line-up of what these dance bands were playing—covers of Latin music. What started to change popular music and what really led to the birth of mbalax were two main factors. One was when the singers began singing in the Wolof language instead of the Spanish that they didn't understand. The first singer who started doing this, who started to import traditional Wolof songs into this popular music is a man by the name of Laye Mboup. Laye Mboup was one of the singers for the band called Orchestre Baobab, which was formed in 1970. This was another one of these dance bands that was formed in conjunction with a night club. In this case it was the night club called Le Baobab. The Orchestre Baobab still exists today. Laye Mboup was the young singer in Orchestre Baobab and he is credited as being the first to bring the Wolof language into this music. So, as I mentioned before, one of the major factors that created mbalax or that sort of made mbalax, was first the singing in Wolof. The second was the introduction of the traditional Senegalese drums

S.R: Would Orchstre Baobab be considered mbalax?

P.T: It would not be considered mbalax, no. Orchestre Baobab have always played more of this Latin style music. So they are considered the old style, from which mbalax music was born.

S.R: But you can't help but notice the clearly West African way of singing in Baobab. I mean the clearly Youssou N'Dour quality—that really tinny, high-pitched head voice, almost slightly nasally sound—is prevalent. There must be subtle hints of sabar drumming because all these guys that are playing Cuban rhythms come from sabar.

P.T: I think the African sensibility in Orchestre Baobab's music has more to do with the vocal styles than with the percussion. The percussion really remains mostly Afro-Cuban, whereas the singing style that Laye Mboup began, and now the current singers of Orchestre Baobab still sing, is a traditional Griot style of singing—yes, it's very sinewy, a little bit nasally, tends to be high-pitched. It has some influence from Islamic music, Islamic chant and a lot of the styles are kind of like praise singing. So you definitely have that influence that starts happening with Orchestre Baobab.

S.R: That's what makes it so hip and distinctive.

P.T: Definitely, yes. So when you listen to Orchestre Baobab at first, you might think, "Oh, this is just some kind of Latin band." And then you listen twice and you think, "Oh, there's something a little bit different about this." That's what makes it so special.

S.R: In your mind, what is the first mbalax band?

P.T: Youssou N'Dour is the first Senegalese musician to coin the term mbalax, and to use that to refer to this popular music genre. As I mentioned, mbalax in Wolof means accompaniment. It refers to the accompaniment part played on one of the sabar drums. So in terms of its usage, the term mbalax has existed for a very long time. But to use the term mbalax as a name for this popular music genre—that was first done by Youssou N'Dour. His was one of the first bands to include the tama, the small talking drum. The band Super Diamono, which was around at the same time that Youssou N'Dour had his band, they were the first to include the sabar. A drummer by the name of Aziz Seck was the first to include sabar in the line-up. I believe that happened in the mid-1970's. There isn't one person who invented mbalax. It's something that came about in the course of the 1970's that grew out of the dance band Latin music of the 1960's.

S.R: How much would you attribute to this new genre of music being tied in with Senegal's independence and this idea of Négritude? How much weight do you give these other things as the reason for this style of music existing?

P.T: I think Senghor and his Négritude movement really helped to lay the groundwork for mbalax music because Senghor and his government lent so much support, both financial and moral, for the arts. I think that if he hadn't done that there wouldn't have been so many of these bands popping up and then growing and then thriving. So it definitely set the stage for it. But then I think that mbalax really kind of took on a life of its own. I think it's interesting to see that one genre of music has remained so popular and has had such widespread appeal like mbalax has. It's a type of music that—yes, it's popular music—but really from the 1980's, '90's and throughout the first decade of the 21st century, it really still dominates the airwaves. It appeals to people of all ethnic groups in Senegal. It appeals to people of all age groups as well, which is interesting because some other genres such as hip hop tend to appeal to a very particular age group of say teens through people in their twenties. But mbalax has a sort of universal appeal that is rare. I haven't seen in many other cultures where you just have this one style of music, which is so popular and so beloved by so many people.

S.R: You call a keyboard a Marimba and most people don't even know what a Marimba is.

P.T.: This is something that came about a little bit later after the sabar drum. But when I say “a marimba keyboard part,” I'm referring to a very specific sound that is used on the Yamaha DX-7. The Yamaha DX-7 is a keyboard, which is kind of the hallmark of '80's rock. If you think about early Madonna and others, this was the keyboard that everyone loved using. What's special about the DX-7 is that you can alter the sounds yourself in a fairly user-friendly way. The Senegalese, to this day still use the DX-7 and they use it specifically to play a highly-syncopated keyboard part, which relates closely to the sabar drums. The sound that they like to use is a sound that's like a marimba, what they call marimba. It's really any wooden xylophone-style sound, sounding like a balafon or a marimba. This kind of wooden xylophone sound is really a distinct aspect of mbalax music.

S.R: How come you never hear real marimbas in an mbalax band?

P.T: It's not something that's native to their culture. There is a family of musicians, the Faye family. There are several different musicians in that family who have been very famous in the mbalax scene. For example, Lamine Faye, who was the leader of Lemzo Diamono. He is a famous guitar player. You have Mustapha Faye, who is perhaps still the best known marimba keyboard player. It was their elder brother, whose name I'm forgetting right now, who was the first to kind of create this marimba keyboard sound.

S.R: What I'm just imagining is sort of like what happened when the swing went to the cymbals in jazz. It became sort of the essential part of the sound and its vocabulary. Or the guitar in Bossa Nova with João Gilberto and those guys. Is that what you're saying?

P.T: It's similar. I think the number one component that would be a good analogy to that would still be the sabar playing the mbalax part. So you have that rhythmic component. But after that I would say the marimba keyboard is the second most essential ingredient that makes up Mbalax music.

S.R: So it's distilled down to phraseology?

P.T: Yes. What's interesting—let's say you wanted to make an mbalax band but use the fewest possible musicians that we could, you could have a singer, you could have a sabar percussionist and you could have marimba. That would really be all you need because if you have the marimba, they can be playing with both hands and the left hand might be playing low parts that basically can replace a bass line. Then you have this highly syncopated style but it's also creating harmonies as well. So it really serves multiple purposes, this part. But I should also mention there's almost a little bit of a point of contention about the marimba keyboard now because it's definitely such an essential part of mbalax music. It's what the Senegalese love a lot. It's also the one ingredient that a lot of times Senegalese bands remove when they play for a Western audience. I personally love that part a lot. I wish they would not remove it when they play for a Western audience but I also can understand that it's disconcerting for a band to play a lot of their music and see people all moving to the wrong beat.

S.R: What if they were just to play that part on a marimba?

P.T: That's just not something that they've considered yet, I don't think. That part is always played on the Yamaha DX-7.

S.R: OK. So you wanted to talk about taasu?

P.T: I'd like to talk a little bit about the relationship between taasu and sabar drumming. Taasu is a predecessor to rap. Taasu is a type of spoken word. It's a rhythmic spoken word, kind of like oral poetry. It's an art form that's been practiced by Griots for many centuries. It's sort of heightened speech. So taasu is something that's very important in traditional Senegalese. What started to happen was that people who were singers would also do taasu. There's a very famous taasukat by the name of Aby Ngana Diop. She was one of the first to record taasu in the context of an Mbalax style cassette. This was a huge hit. Her cassette, which was called Liital, came out in 1994. Again, she was a traditional taasukat, which means a person who is a practitioner or performer of taasu. She performed taasu and she made this cassette, which became extremely popular. So this is the first commercial recording of taasu accompanied by mbalax background. This one song that she did taasu for became extremely popular and was a piece called “Dieleul.” “Dieleul” means “Take It,” and it goes like this: [sings lyrics in Wolof]. It just means, "Take it, take it, take it. If you want it, take it." Then it kind of continues along those lines. So it has this really catchy phrase. There's a very close relationship between taasu and sabar drumming. Many bakks or musical phrases are actually derived from the spoken word, in particular from taasu. So you have, in 1994, Aby Ngana Diop putting out this wildly popular taasu recording called “Dieleul.” In this piece she is being accompanied by members of the Mbaye Family Drum Troupe, who are led by a drummer by the name of Habib Diagne. Anyway, so you have the creation of taasu and then you have a bakk sabar phrase that is based on this. Aby Ngana Diop sadly passed away suddenly in 1997. So the Mbaye Family Drum Troupe loved this bakk that was played with this taasu. They continued to perform the bakk in the context of their traditional sabar drum performances, so at drum and dance parties, baptisms, weddings, et cetera. So this bakk that was derived from the taasu or spoken word lived on for several years from 1997 to 2002. Even now it is still played. In 1997, the year of Aby Ngana Diop's death, another artist by the name of Cheikh Lo, who is a very famous Senegalese singer, came out with a recording of a song called “N'Dokh,” which is about water and the virtues of water, why water is so important. We need it in so many different ways. Cheikh Lo was working with Thio Mbaye, who is one of the leaders of the Mbaye Family Drum Troupe and they decided to perform this bakk that went with Aby Ngana Diop's song. They played this bakk in this new song by Cheikh Lo. This gets a little bit complicated, but you have the taasu being created by this woman Aby Ngana Diop. Then you have a bakk—that is, a sabar drum phrase—that's derived from the spoken word. That continues on. Then the bakk gets inserted and imported into another new mbalax song by Cheikh Lo. That was in 1997. Then in the year 2000, Thio Mbaye, the drummer of the Mbaye Family Drum Troupe, came out with his own cassette. He had this sort of salsa flavored piece that was called “Parena,” which means "It's Ready". He also had this bakk played in this song. But he also created new taasu, or a new spoken word, that was derived from the bakk. So you have in this case a kind of transformation, which is really interesting. You have spoken word creating a drum phrase. The drum phrase lives on, gets imported into different pop music songs. Then you have the drum phrase then creating even newer spoken word.

S.R: In a full cycle.

P.T: Yes. Yeah, in full cycle you have the same bakk with the original taasu, "dieleul, dieleul, dieleul" that appears in the music of Lamine Touré and Group Saloum. Lamine Touré is a Griot percussionist from the Mbaye family who has since immigrated to the U.S. There was a performance about two years ago when this young man by the name of Demba Sene came and guested and did the taasu with Lamine's band. Demba is actually the son of Aby Ngana Diop, the original creator of this taasu. So you have this amazing kind of transformation and immigration of this music, this spoken word, and the drums and the drum phrase being brought to Boston and being performed in a new context of a Boston-based kind of mbalax fusion band with a funk style but with one of the original drummers who played this bakk back in Senegal as well as the son of the original creator of the taasu. So I know that might have been really convoluted but it might be better explained with the music playing in the background.

We haven't talked yet about the social issues and what mbalax songs are about. Part of why I think mbalax has had such a widespread appeal is not just the musical elements, which people love inherently because of the inclusion of the sabar drums, but really it's what mbalax singers sing about. The lyrics of their songs are extremely important and they cover a wide range of issues, a lot more social issues such as religion, Islam. There are praise songs to various religious leaders, Muslim religious leaders. There are a lot of songs about social and moral issues, how one should treat other people, how important it is to respect your elders, how important it is to look after your children. There are also songs that talk about the plight of people who immigrate to other countries. Immigration has been a very important topic in many mbalax songs because in Senegal, for many people, because of the high rate of unemployment, it is expected you should leave the country. If you can at all possibly get a visa to go to Europe or to North America you will do it and you will leave. You may have heard several years ago - this is I think still happening but has maybe been curbed by government somewhat - but there has been a huge problem with Senegalese immigrants taking boats to the Canary Islands in order to eventually reach Spain. I believe in the year 1996, for example, there were over 30,000 mostly Senegalese immigrants, some from other parts of Africa, who departed from Senegal and took small rickety boats and would ride in these boats for one to two weeks across the ocean to get from the coast of Senegal to the Canary Islands. It's thought that, let's say, out of 30,000, over 6,000 perished or disappeared along the way. They would pay huge sums of money to be brought there. In many cases they have then, after arriving in the Canary Islands, because the immigration issue has been such a problem, been put on planes and sent back to Senegal. But the fact that so many young men in particular are willing to risk their lives to leave the country shows that there has been a serious problem even before the current economic crisis, which has only made things worse. But because of the high rate of unemployment and how hard it is to support yourself and to support one's family, people really want to go.

There is a wonderful mbalax song by one of the top young mbalax singers of the day now. His name is Pape Diouf. Pape Diouf came out with a song a number of years ago. It's called “Partir” or “Partira.” It's like “you're going.” The song is definitely a pure mbalax song. You will hear the melody is actually taken from a famous song by the opera singer Andrea Bocelli, who is a blind Italian singer. So there is this reference of Italy. In the song Pape Diouf is talking to his girlfriend and saying, "I've just gotten a visa. I am expected to go to Italy because I'm the eldest and my parents want me to go. This is the only way I can help the family and make money. But I'm going to have to leave you. Will you wait for me? What's going to happen to our relationship?" This is actually an issue that many Senegalese immigrants have to deal with. There is extreme pressure to leave and the desire to leave. But oftentimes the situation that awaits them in other countries isn't so great. They are often working very hard to send money back home. In some cases, if they are not legal, they aren't able to return home to see their families, their girlfriends, their wives. It becomes a very difficult life and a very difficult situation for many people.

S.R: So what is a Griot?

P.T: Griots were keepers of oral history and they are also the hereditary musicians caste in many African societies.

S.R: What is the percentage of Griot musicians that are in pure, typical mbalax bands?

P.T: In general, most mbalax singers are Griots. Not all, but maybe 80% or so are from Griot families. Youssou N'Dour’s mother was a Gawlo, which is a Griot from a different ethnic group, almost like a Griot to the Griots. Thione Seck is another very famous Griot singer. Yes, most of the singers tend to be from Griot families, although it's not exclusive

S.R: So are there songs that criticize polygamy?

P.T: Yeah, there are songs that talk about the importance of respecting women. There are songs that give an example. For example, there is a song by Alioune Mbaye Nder, known as Nder. He had a song called “Lënëën,” which came out more than a decade ago in 1997. It was a love song. The chorus says, "Love is something else." But it says, "I respect women. I respect the privacy of women." This song really helped to propel him to enormous popularity because women loved this. Here was a song talking about how wonderful women were and how much you should respect women. A number of years later, when Nder took a second wife, I think it's fair to say that his popularity took a hit because the same women who were his primary fan base felt somewhat deceived by him. How could you talk about this respect for women and suddenly you go and you take a second wife? So that's one example. Nder has had other songs. This one song called “Georges” is about a man who is always going around and wasting money on things and not paying attention to his wife. This was also a song that was very popular and that women liked because of the moral story that went along with it.

S.R: So they have a right to moralize.

P.T: Yes, exactly. They have a right to moralize. They are born into this tradition and it is their occupation that they are born into, to learn the oral history, to praise people, to moralize. I think in modern days you see this definitely—it's not just praising people. But you can have Griots coming up and singing praises to someone at a baptism and if that person decides to be stingy and not give them money, then they might start saying some not so nice things about the person and embarrassing them in public because that's what the power of the Griot is. They are the masters of the word. They are also the masters of various instruments.

S.R: So how much of it is, when you have messages like being polite, respecting your elders, respecting women, trying to make a bad situation better, just basically having a positive or constructive voice in society versus what is tradition, what is history. Is it a mixture of the two or what is it?

P.T: I think it's a mixture of the two definitely. What the Griot is doing is they are taking traditional values and trying to propagate them. What's interesting is what Griots do and mbalax music in general does—the songs tend to be, as I mentioned, for didactic. But they are always constructive in terms of advising people what they should do. There is very little criticism. That is left to the rappers and the hip hop artists. Those are the people who will outright criticize the government, criticize corruption, things of that sort. But you don't actually see much criticism, outright blatant criticism in mbalax music. Again, I think this does link to the fact that mbalax grows out of a Griot tradition in which you are more expected to praise people than to really cut them down in such a public way, unless they really deserve it.

S.R: That could be another reason why it's so universal and why it's well liked by everybody.

P.T: Definitely. Definitely.

S.R: So, in a general sense, is there an easy distinction you can make of the vibe of pre-independent Senegal versus the vibe post-independent?

P.T: I think definitely after independence, there was a great sense of optimism that there was independence. That was where all these dance bands came about. People wanted to celebrate. Here they were finally independent from the French colonial powers. So that really helped to give a rise to this popular music and I think over time as people have become disillusioned with the government—and that sort of happens in waves—there has been more criticism and then there has been changing of parties. Senghor was President for twenty years and he was succeeded by his handpicked follower, who was Abdou Diouf, who was President for the next twenty years. So although they had independence, you had forty years of rule of one party and just two people. It was in the year 2000 that Abdoulaye Wade, the current President, took power. This was also a time of great optimism, a time of change. We see this now with Obama, I suppose, in the U.S. But there was this real feeling of optimism for change. I think since then, now that Wade has been President for nine years, there are starting to be people disillusioned with him and his government as well. Again, if you go to the music of the rappers and hip hop artists, that's where you're going to see more of that.