The Nigeria that inspired Fela Kuti’s most seminal works was a Nigeria riddled by violence and civil war. The country was ruled by the military dictator Colonel Olusegun Obasanjo, who defeated Biafran separatists by masking brutality and torture as law and order.

It was against this backdrop of suppression and conflict that Fela produced Roforofo Fight (1972), Water Get No Enemy (1975), and Zombie (1977)--some of his most poignant and politically charged records. On Zombie, Fela singles out the soldiers of the Nigerian army not only in his lyrics —“Zombie no go think, unless you tell am to think”—but in the album artwork, which features a superimposed Fela yelling into a microphone directly in the faces of these very soldiers.

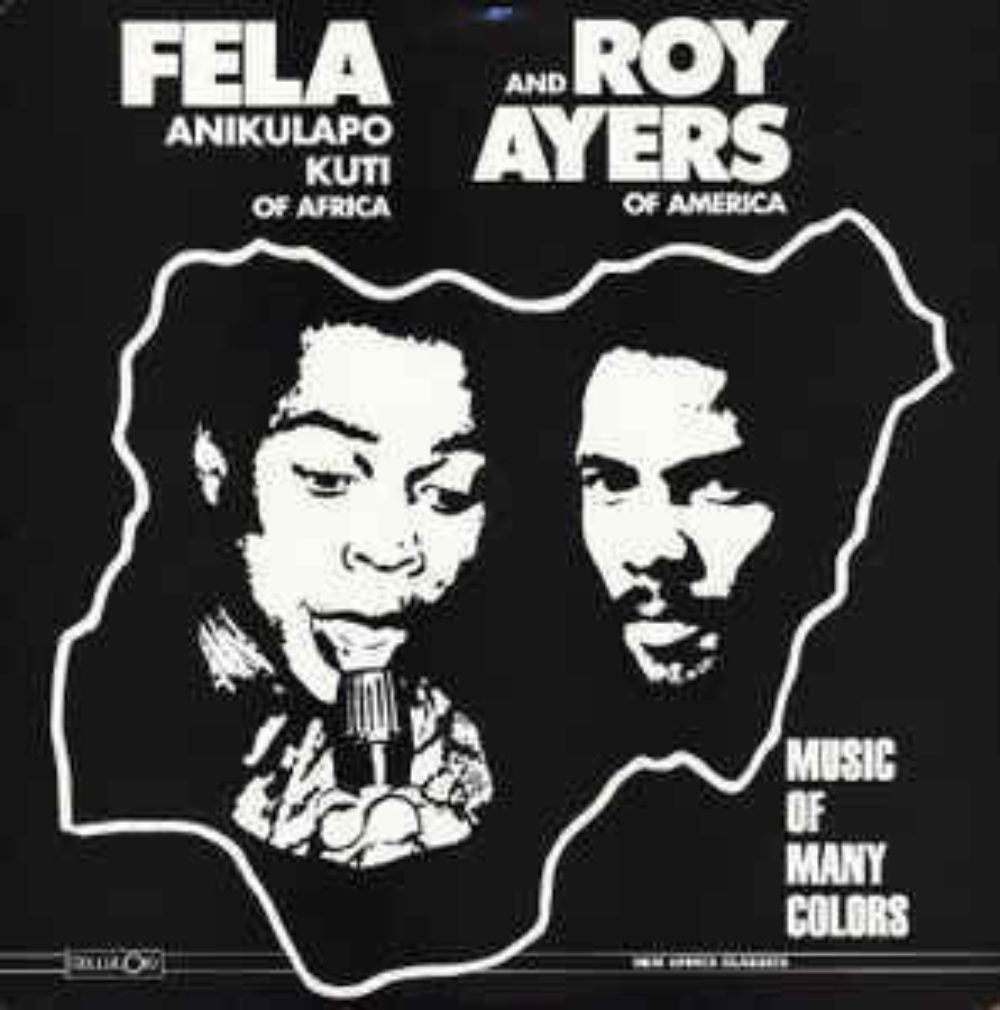

The Nigeria where Fela met the American jazz musician Roy Ayers at the end of 1979 was markedly different. The dictatorship had ended, Fela’s arch nemesis Obasanjo was out of office, and Nigeria’s first democratic elections were held earlier that year in August. To punctuate such a hopeful turn of events, Fela and Ayers played a three-week tour in Nigeria’s major cities and collaborated in 1980 on a joint project called Music of Many Colors. On the two-song LP they lean heavily into the ideas of pan-Africanism and Afro-futurism, even making a bold and ultimately far-off prediction about what they thought the world would look like for black people in the next 20 years.

The first track off the LP, titled “2000 Blacks Got to Be Free,” begins with the vocals of Ayers as he sets a directive for the project: “We’re hoping that by the year 2000; we know that by the year 2000, that’s even better, everybody will be knowledgeable.”

Knowledgeable of what exactly and who he refers to as “everybody is somewhat unclear. The syntax of the lyrics shifts from being imperative to aspirational to prophetic. The year 2000, according to Ayers, could, should, or will be the year in which a unified African diaspora will be free of oppression and white supremacy. A year marked by harmony and positivity. Throughout the song, Ayers offers a litany of concepts to think about--unity, righteousness, positive vibes, togetherness, happiness, Africa, black Africa, the mind, family — but he doesn’t elaborate on what exactly he wants us to think about them. The song’s message is opaque, that is, until Fela comes in with a tremendous saxophone solo around the 10-minute mark, deciphering, as it were, Ayers’ message about this not-so-distant future, making it crystal clear.

The two musicians share the track well. It begins with the blast of a trumpet and the iconic drum rhythm easily recognizable in Fela’s Afrobeat. Soon after, Ayers makes his musical presence felt as he plays the vibraphone in a call-and-response with a slightly fainter trumpet. Typical of a Fela composition, the song is pretty long, lasts a little over 18 minutes, and the bass line is very, very funky.

Then in a series of breathy chants, Ayers calls to Fela to return and impart some more wisdom. Fela’s only vocals on this track is a grunt of acknowledgement to Ayers, as if Fela had nodded off and needed to be awakened, or maybe needed to be convinced to play in the first place.

Fela’s skepticism would be justified. After all, Nelson Mandela was still in prison and it was only two years prior that soldiers had raided Fela’s home, beaten him, and assaulted his mother. Even amidst Ayers’ pleas, the year 2000 must have seemed ambitious for the complete reversal of imperialism and government-sanctioned violence. However, they weren’t alone in this prediction. In the 1974 film production of Space Is the Place, the American jazz composer Sun Ra leads his mystic Arkestra band to a far-away planet to prepare for the year 2000. The movie depicts a cosmic battle between Ra and a villain called the Overseer, in which they gamble for the lives and futures of young black people. Ra wants to protect them, the Overseer intends to exploit them.

The Overseer relies on the stereotypical pitfalls of urban black life — substance abuse, prostitution, violence, and poverty. Meanwhile, Ra has found a way to transport the youth through music.

In a pivotal scene in the film, Ra appears at a youth center in an attempt to recruit young people to attend his concert and therefore join him on his mission to this extraterrestrial black utopia. The kids aren’t convinced. Even though Ra appears out of thin air, his platform shoes and ridiculous costume invites skepticism about whether or not this is all just a gimmick to sell concert tickets and boost record sales.

“You don’t exist in this society,” Ra tells them. “We are both myths. How do you think you’re going to exist? The year 2000 is around the corner.”

Four decades have passed since Fela Kuti and Roy Ayers set out to predict the future and all across the world, swells of protestors are today denouncing police brutality and thinking about the significance of black lives. It’s a bleak exercise to compare the future that the duo envisioned on Music of Many Colors with the reality that we’re living in today. Black and brown people in the United States and across the diaspora are fighting to not be made into myths, as Ra would say it. We are fighting to exist in society.

But despite the over-zealous nature of the LP, what’s far more profound is that Fela and Roy came together with a sense of urgency in their optimism. Witnesses to progress and pain, the two musicians were courageous enough to put a goal for liberation. The world they wanted to create needed texture and rhythm and could only exist by recognizing the potential in the other.

“2000 Blacks Got to Be Free” is such a radical concept because it challenges the listener to consider that if they’re not free, then no one is.