Blog December 20, 2009

Seun Kuti on FELA!

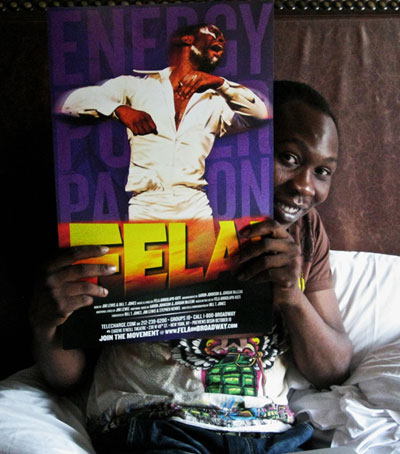

In late December,2009, Seun Kuti came to New York City to see the Broadway show FELA!, which presents the life of his late father, Fela Anikulapo Kuti. Seun now leads his father’s band, Egypt 80, and along with his older brother Femi, carries Fela’s torch for a new generation of Nigerians. Afropop was curious to know how Seun felt about seeing Fela’s life laid out on a New York stage. Seun knows as well as anyone that Fela himself was extremely protective about his art and image. In this exclusive interview, Afropop’s Banning Eyre, Sean Barlow, and Matt Payne spoke at length with Seun in his hotel room, and the conversation roamed well beyond the subject of FELA! on Broadway, to Seun’s plans for a second CD, and even his opinions about films, Hollywood, Nollywood, and even Bollywood.

Banning Eyre: Seun, welcome back to Afropop.

Seun Kuti: Yeah, hello.

B.E.: You’ve come to New York to see FELA! on Broadway. So, tell us, what do you think? Is this the first time you are seeing the show?

S.K.: I have seen it twice now already. It is a great show. And it is Broadway, you know, so everything is a bit dramatized. The story is what is most important, and I think a very important part of what my father stood for was portrayed in the play.

B.E.: You feel like it is there, and that it is true to his spirit?

S.K.: Yes, his spirituality, his fight, his struggles. Yes, of course.

B.E.: Tell me what it was like the first time you saw it. Did you see the play with Sahr the first time? There are two different actors who play Fela.

S.K.: I have seen only Sahr so far. I was with Kevin yesterday watching Sahr [Ngauja] in the show. Kevin is a good friend and Sahr is a good friend. I am going to catch Kevin [Mambo] on Wednesday because I missed him on Saturday evening. I couldn’t make the show; I was jetlagged. Yeah, but I have caught Sahr twice now.

B.E.: So what was it like the first time you saw him walk on stage as your father?

S.K.: Well, you know, here in New York, maybe it is not often people walk up to me as my father. But in Nigeria, a lot of people try to impersonate him, dress like him, and come on stage every time we are holding an event. You know, try to act and stuff. So, it is interesting to see it on Broadway. And Sahr, you know, he is a funny guy. He is someone I want to see acting, and he changes. He has the walk and the talk. I was practicing with him some extra gestures. It was fun. It was good. He does a good impersonation.

B.E.: You say you’ve known him for awhile. How did you meet him?

S.K.: Well, I met him for the first time last summer. They were still off Broadway.

B.E.: That is interesting that in Lagos you have a lot of Fela impersonators. Is that like we have Elvis impersonators here?

S.K.: Of course, a lot. You know, he is like an icon. A lot of people do that when we have events and stuff, most especially. But the misconception some people have is that he only wears underwear. He doesn’t only wear underwear.

B.E.: Oh yeah, that’s right. I saw that wrong. They said he performed in his underwear and I thought, “No, no, no...” [Laughs]

S.K.: Misconception.

B.E.: Tell me what it was like the first time you saw it. Did you see the play with Sahr the first time? There are two different actors who play Fela.

S.K.: I have seen only Sahr so far. I was with Kevin yesterday watching Sahr [Ngauja] in the show. Kevin is a good friend and Sahr is a good friend. I am going to catch Kevin [Mambo] on Wednesday because I missed him on Saturday evening. I couldn’t make the show; I was jetlagged. Yeah, but I have caught Sahr twice now.

B.E.: So what was it like the first time you saw him walk on stage as your father?

S.K.: Well, you know, here in New York, maybe it is not often people walk up to me as my father. But in Nigeria, a lot of people try to impersonate him, dress like him, and come on stage every time we are holding an event. You know, try to act and stuff. So, it is interesting to see it on Broadway. And Sahr, you know, he is a funny guy. He is someone I want to see acting, and he changes. He has the walk and the talk. I was practicing with him some extra gestures. It was fun. It was good. He does a good impersonation.

B.E.: You say you’ve known him for awhile. How did you meet him?

S.K.: Well, I met him for the first time last summer. They were still off Broadway.

B.E.: That is interesting that in Lagos you have a lot of Fela impersonators. Is that like we have Elvis impersonators here?

S.K.: Of course, a lot. You know, he is like an icon. A lot of people do that when we have events and stuff, most especially. But the misconception some people have is that he only wears underwear. He doesn’t only wear underwear.

B.E.: Oh yeah, that’s right. I saw that wrong. They said he performed in his underwear and I thought, “No, no, no...” [Laughs]

S.K.: Misconception.

B.E.: Misconception. And they printed that in the New Yorker too. They are supposed to be careful up there. But anyway, a little bit more about the play and the way it tells your father’s story. You said that it was a bit dramatized. What do you mean by that?

S.K.: Yeah, of course, it’s a play. So that is exactly what I mean. It is dramatized. It has to be interesting. But the story stayed the same, and that is important. Some of the stage acts, for example. Fela did not have people flipping on stage, but on Broadway it has to be done to make the show lively and interesting. For me, I went to the show and I was hugely impressed. You don’t expect it to be exactly how it is. It’s a play. That is exactly what I meant by the extra drama that was put in there. And I appreciated that because it is extra effort trying to make it beautiful.

B.E.: The play summarizes aspects of his life very, very quickly. There is that section that talks about how he created Afrobeat. In five minutes, you have highlife, traditional African drumming, jazz and James Brown. All of this stuff, and then it arrives at Afrobeat. What did you think of that section, speaking as a musician?

S.K.: For me, it is the story being told. That is what is most important. That is the question I asked. And you know, even if it is five or ten minutes, I mean, as long as the proper message is being put across. Afrobeat was influenced by all of these genres. In his autobiography, he said it already, and to most people that influenced my father, that is not a surprise. Even if it takes them one minute to do it, as long as they tell the right story, which they did, how long it took is not that important I guess.

B.E.: Yeah, it is actually very powerful. A lot of people who see this play don’t know your father’s story. And the way they do it where they hear all of this music, and then you hear Afrobeat; it is very revealilng actually. I think people who would have no idea, and I’ve never really seen it presented quite that efficiently. You know what I mean?

S.K.: Yeah, well, on Broadway you mean?

B.E.: Yeah, I was just impressed by that segment. I also really find very interesting the part that deals with Sandra Isadore, where he is arguing about racial politics in America as opposed to in Nigeria in the 1970s. That was before your time, but did that ring true to you, that section with Sandra?

S.K.: Yeah, of course because I grew up with my dad and I understand his life story from a personal point of view. And before he met Sandra, he was just like every other African young man who didn’t read much into African history. He just took conventional wisdom as truth, just the way people take the conventional wisdom that he is wearing pants on stage as true. It is just conventional wisdom. So back then in Africa, people used to think that Africans were in the bush. You know, they didn’t understand African history. But the African Americans here who didn’t have a connection to home, the only thing they could hold on to was the history and they knew the history of black people, which Sandra opened his eyes to. It said black people have been great before, which was something that was not taught back home.

Even up to now, I cannot say that I studied any relevant thing about the history of my people in school. Everything that I have learned about Africa I have learned independently, not from our educational system. It just touches a few irrelevant topics about the history of Nigeria, not even Africa. Nothing gives African youths today a sense of pride in who we are, even up to today. It is interesting that people know that it was Sandra that gave my dad that knowledge of being able to understand how great his people are, and to see that black people have done great things. It is not that we are just monkeys that white people came to train, like pet animals and brought us civilization. We were civilized before. They brought us their own kind of civilization. So, I think in that aspect, the story was told because that was what really happened. As I said, it has to be dramatized. I don’t see anything wrong with the way the story was told as long as the message is passed across: that Sandra taught him something about Africa. It’s a fact.

B.E.: So you probably got a better history education at home than you did at school.

S.K.: Well, yes, and even independently and as a young child I wanted to know more because I always realized that Nigerian education was boring. So I have always been learning from a very young age independently of education. You know, education is not learning. Most people mistake education for learning; it is two different things.

Sean Barlow: A big part of Fela on Broadway is the story of your father facing down the authorities, facing down the regime, facing down the dictators of his time, and suffering for it, of course. I know you in your songs have also been critical of the powers that be in Africa. You are continuing your father’s critique of power. But what has changed since Fela’s time?

S.K.: Not a lot has changed in Africa between the 70s and today. I always say to people, the way that Africa has developed has shown really that slavery has not ended in Africa. As time has progressed, the poor have gotten poorer and the rich have gotten richer, and fewer in number because in Africa today rich people are like a monarchy; they marry only rich people, they do only things among themselves. It is very detached from the common man. The elites are the elites. Nobody cares about what is happening to the man on the streets. In Africa today, I don’t see a lot of development from the aspect of the civilians or citizens. There is a lot of development for the industrial aspect, the money making part of Africa: telecommunications, construction, oil. These money making industries, for government officials, are well-developed.

They have big buildings and ultra-modern equipment, and they work. But the things for the common man, human rights, water, light, food, education, healthcare. What the people need are the things that are lacking in Africa today. I know a lot of expatriates in Nigeria who work for oil companies that tell me that they never want to leave Nigeria because they have never had so much fun in a place and it is so nice making as much money as they are making. So, it is how it is in Nigeria. That is a picture of what is going on everywhere in Africa, not only in Nigeria. Everywhere there is development, it is only development of commerce, it is money-making development. I have not seen any concrete development. Because the real development that matters is investment in the people. No company comes to Africa to invest in the people. Everybody comes to invest in some kind of business. Even when actors and actresses come and adopt a baby and spend five thousand dollars on the pipeline, the only thing that it does is show for the government as well as government sponsors maybe a month later when they are earning two-hundred-thousand, five-hundred-thousand dollars for one gig. So for me it is not investing in a cause, and the government is not investing in a future for the people of Africa. So that is that.

B.E.: Let me ask you about the role and the status of Afrobeat music today in Nigeria. When we talked two years ago you told me about how it was a difficult situation where you had a very loyal fan base but you did not have a lot of support from media and government. What is it like now?

S.K.: It is still the same, still the same. That is never going to change. I don’t see Afrobeat in Africa ever being sponsored by any corporate body or supported by any government parastatal. That is what makes sense. That is what makes sense because it would be crazy if the government is suddenly helping Afrobeat and all companies are sponsoring Afrobeat. Then there is something wrong. Probably activism has stopped, and now we are seeing the interest in it. I guess if I get a call from a government person offering me sponsorship, I would have to review all of my lyrics again. What did I just say? Did I just say something where I could be misconstrued? Support! So, this is where it is. For me, if you are an activist, you cannot mourn about things like this. Every job has its dangers. It is one of the things you go into knowing this is the caution and this is what is going to happen. And you can’t keep mourning about it. I am not as rich as I would like to be, compared to my talents. Because I see a lot of artists in Nigeria that don’t have a tenth of what I got, going “Mh, Mh, Mh, Mh, Mh, Mh, Mh”, making all of the money because that is what is being promoted. But for me that is not what matters. What matters is the message. My father as well had contemporaries in his time that made a lot of money and that had a lot more money than him, even today. But they are never going to have their life story told on Broadway.

B.E.: Do you think it’s at all uncomfortable for officials of the Nigerian government to have Fela arrive on Broadway? I mean regardless of what you think of his politics, he is a Nigerian artist who is being recognized in one of the highest cultural venues in the world. You have to feel an element of pride. How do you think it makes officials feel to have this recognition for Fela?

S.K: Should I tell you the truth? The truth is that they actually believe it is not happening. You know, if you don’t really want to see something, you can make yourself believe it is not there. Maybe they would come and not even know it is there. They would come in a non-official capacity. Definitely a lot of Nigerian officials would have come here, without seeing the play. That is how they are. Our state is Lagos state, which is not in the federal party. So their policies are very different from the federal policy. Federal officials would not be caught dead in an official capacity at a Fela event. They want a good future, and the federal government is still stealing money. So, I don’t think they would support Fela in public.

B.E.: Even on Broadway?

S.K.: Even on Broadway. They don’t care about Broadway. What is Broadway? They don’t care about anything. These African rulers, all they care about is where the next big bag of dollars is coming from. They don’t care about anybody, anything.

B.E.: But isn’t it possible that bags of dollars could come from having one of their artists being recognized this way? If they thought about it the right way..

S.K.: But he is not one of the approved artists. You have to understand; that is how it is. If it was Sunny [King Sunny Ade] and his life on Broadway, trust me they would be there. All of them, happy as hell. So if you want to get them there, just do a show on Sunny. They’ll be there.

B.E.: I spoke with your sister Yeni about it when she was here a month ago. Like you, she loved the show, but after we had finished our interview, she said to me, “Well, there was one thing that wasn’t right about that play. And that was the fact that right at the beginning of the play, Fela says that he is planning to leave Nigeria.” Yeni said to me, “Fela would never leave Nigeria.”

S.K.: Fela left Nigeria. He had put himself into self-exile. Maybe she has forgotten that he went to Ghana. Fela would not leave Africa, but he left Nigeria for awhile. In fact, he did not want to come back. The Ghanaian government deported him because he was already inciting the Ghanaian students. Just less than a year he was there. He was already giving them hell as well. I think he was Ghana between ’78 and ’79.

B.E.: So that was after the raid, just the way it is in the play.

S.K.: Yeah. It was in the book. Have you guys read the book?

B.E.: Well, yeah, absolutely.

S.K.: Not the choreographer’s book, but Fela’s autobiography by Carlos Moore.

B.E.: Carlos Moore. Yeah, I have it.

S.K.: This Bitch of a Life. I know you are not the New Yorker, but do your research. F***in’ hell.

B.E.: No, I just wanted to hear it from you.

S.K.: Okay, if you put it that way. George Bush! You just George Bush-ed it right now. [Laughs] I knew it, I knew it, I knew you were all bums. You just wanted to get the evil guy out. [Laughs]

B.E.: Let me ask you this about the play. I feel that everything you see about Fela on the stage there feels very true. It feels true to everything that I’ve read about him, and I saw him perform a number of times. But I think that there are some things about him that you don’t see in the play. And I was talking to Yeni about this as well. There is a tough side to Fela, the way he was with his musicians, for example. You were with the band a lot; you know very well what it was like. Talk to me about things that you remember about Fela that were sort of beyond the scope of the man we see on the Broadway stage.

S.K.: Well, the thing is, it is impossible for them… I’ll be open about this, I don’t think they had the right consultation team for the play. You know, the people they had with them, I’ll say it anytime, were guys that just made money from Fela and were never really close to him, never really knew him, never stayed with him for longer than ten years at a particular time. And there are people alive today that stayed with Fela for thirty years. Sorry. Some of them are in my band now for forty years. But what I am saying, they knew thirty years of his life. There are women that are still alive that lived with him for twenty years of his own life. There are people like that that knew him very well, that were never consulted. They were all of these people that he actually stopped talking to because they betrayed him and they left him. They were the ones brought together to this place. They are only human. They must have lost touch with a lot of little things about him. And at the same time, I said the play is for drama. People always have to remember that. A play is about drama, and it is to bring out the best side of everything, the full side of everything. In the little I know, if showing that toughness is not assisting the story in any way, there is no way they were going to use it, even if they knew about it.

B.E.: So what would you say is important to know about Fela that is not in that play?

S.K.: I think the only thing, if anybody ever read my forward to this play, because I did a little write-up introduction to the play… If anybody ever read my part, I said, “Fela’s life and struggle has always been about the elevation of the common man in Africa and the betterment of his future.” Any way Fela is portrayed, that is the message that is carried on there because his music will be celebrated and his message will be put across. So for me, what is ultimate about this play is not what is in it or what is not in it. It is what people that are now open to Fela will have to live with. They will live with the fact that now they will want to know about this man and to understand his struggle. I know people will be involved in the movement of the people. You understand what I am saying. So for me, it is not about how well they were able to do it. The success of the play for me is Fela’s message is understood by more people that would never had had the chance to understand him if it was not brought to this place. For me, it is all about the growth of the movement, and I see this as a big step in the growth of the movement. Sahr and the producers said, “If Fela was alive, we probably would not be able to do this play.” If he was alive, they would probably not get the permission to do a play like this. Never.

B.E. and S.B.: Why?

S.K.: Because first of all, he would never agree for his music to be shortened while they are trying to do the play. He would say, “If they are going to do it, why aren’t they playing those Mozart songs? I did that piece for four hours. That is what you are going to do. You are going to play my song the way it is written, every time.” That is him, you know. For him, his Afrobeat… There is another misconception. When I read the story, it says that Motown gave him a deal that he turned down for the spirits. Then he changed his mind, and went back to Motown. But then Motown had already found Femi, and Motown turned him down. Fela never changed his mind about Motown. He never went back. He turned them down. They gave him a-million dollars, and he said no. He never went back to say yes. They stayed with him in Lagos for a few days trying to get him, but they couldn’t. And there was a guy called Mikel Avantario that brought this guy; he was a friend. And so he took them, because he didn’t want to leave empty handed, so he took them to see my brother. And after that Motown collapsed a few months after. Which when I was saying at the Shrine, you see, the Gods were not wrong for telling him not to sign with them. If he had signed with them, they would have collapsed a few months later and all of his stuff would be, you know, gone.

B.E.: So he didn’t sign. Was it because they wanted to interfere artistically or they wanted him to shorten his songs?

S.K.: No, he just told them no because the spirits said, “No”. And he was really serious, and he said he couldn’t do it with them because he consulted his gods and they didn’t want him to do it. That was the reason he gave, and he never went back on it. So, I don’t like it when I read, and they make him look like this crazy man that talks to spirits and goes back to try and get the money and they turn him down. He was never that kind of guy.

B.E.: Well, I think that you are right, that the play doesn’t get into anything like that. What you come away with is the message.

S.K.: Yes. And I think that is what is most important. Because for Fela, Afrobeat was not just music, it was like his baby so he didn’t want to give it away. He didn’t want it to be compromised because he felt like if you said, “I want to take ten minutes off,” it was like cutting off his baby’s leg. For him, it was really personal. That is why I was thinking that this play could never have been held because Fela would be like, “If they want to do a play on my life they should call it ‘My beat in Nigeria’.” Even if they call it “My beat on Broadway.” And when he sees that it convolutes his seventeen group orchestra playing, maybe he will want to act himself. [Laughs]

S.B.: That raises an interesting question. What do you think your fans and Femi’s fans would think if they brought this Broadway production to the New Africa Shrine in Lagos? What would be the reaction?

S.K.: It would be great. It would be great. And I think a lot of people would come through to see it as well.

S.B.: When you first saw Antibalas performing on stage as the people were streaming into the theater and you heard them throughout the play, what did you think of Antibalas?

S.K.: They are good, but I have to disagree with Questlove, as he calls Antibalas the best Afrobeat band. Maybe they are the best Afrobeat band in New York. [Laughs] But they are a tight band. I have jammed with them before, and I have known them for a long time. And I think they are good enough for the play. But they are not the best.

B.E.: Who do you think is the best? Well, I guess we know, don’t we?

S.K.: I am. [Laughs] I have got the best band, you know. Definitely.

B.E.: Okay. Who is the second best?

S.K.: I don’t know. I don’t deal in seconds.

B.E.: Fair enough. But here is one second you might deal with: your second record. Can you give us a preview?

S.K.: Alright. Well, you know, the second record becomes the first because it is going to be the newest one. We are going to record soon. I am really excited. I am practicing, and we are still rehearsing the songs though with the band. It has been a really tough these past two years—going everywhere. We don’t have time. We had only worked on maybe thirty percent of the songs on the album. Then this summer we played a worldwide tour. So finally we have been home for the last three months, and we have been working and are seventy percent done, which is a huge leap in three months compared to the thirty percent that we did in a year, basically.

B.E.: Anything to preview about what is going to be different, what is going to be new, some of the things you are going to talk about?

S.K.: Well, for me, what we talk about is Africa, every time with Afrobeat. Afrobeat is about the development of Africa properly. Not industrial development. You have to get the foundation and the basics set. It is the African people that can carry Africa. Even if the African people are weak, what strength can they use to carry Africa? So right now we have an Africa that is being carried by Europe and America, on aid, so-called aid that is actually kickbacks for being able to exploit the continent. They have been giving aid to Africa since the 70s, and they have been increasing by two-hundred percent almost every year. And the suffering in Africa has also been increasing by two-hundred percent every year. So, I think with this aid and the suffering, we have something together. The more aid we get, the more our suffering is in Africa. It is important for people to think like this to realize and think outside of the box. Don’t see these handouts as free handouts. The more our government claims that we are getting help from IMF, UNESCO, Paris Club, Monsanto, and all these companies, the more people are suffering.

The Monsanto issue is the worst issue. Since Monsanto has come to Africa, food prices have… I can’t even explain how high. There is no percentage, maybe one-thousand percent. That is how much food has increased in Nigeria in the last five years alone. These farmers are poor already. Now you are making them pay for the seeds that they even use to plant the food. You know, more costs. They don’t have the right transportation; most of the food is rotten before it can even get to the market because they don’t have the right storage. So the few items that can get to the market, it is sold at… You can’t store this f***ing GMO food. It has expiration dates. They spoil in less than four of five months if they are not consumed. Not to talk of the diseases they cause, how much it costs for the pesticides, and the diseases the pesticides still cause in all of Africa. But the government, because they still need the aid from UNAID, they will put pressure on the government to make sure that the farmers are forced to use this product. Then, they will make people pay huge amounts of money for food, and then they will blame it on something else. Oh, there is war somewhere. That is why food can’t get there.

The way Africa is, it is shame for our governments in Africa to sit there looking for money to feed five hundred thousand people in Sudan. What is the meaning of that rubbish? Africa is full of land. Why can’t we grow food? People were growing food before the white man arrived, and we were eating. So now how come we can’t eat? I don’t think there are more people in Africa than arable land. I don’t think so. Africa is not that developed. Everywhere there is arable land still. Even in Nigeria, as developed as Nigeria is, if you travel by the roadside, you will see what I mean. Where is developed? Everywhere is just forests that can be converted, at least bits of it. In Europe and America when you are traveling the country road, everywhere there is farmland, feeding the people. In Africa you see churches, huge churches. People plant feet instead of seeds in those places.

S.B.: I have a follow up question on the new album. When is it going to come out?

S.K.: We hope next summer.

S.B.: And it comes out in Nigeria first?

S.K.: No, no. Nigeria last, every time. If I bring it out in Nigeria first, I might as well not have any release anywhere. Those pirates would just help me do a worldwide release. They would be like, “Look, Seun Kuti, he released it here. Just, don’t worry. We will do the rest.” [Laughs]

S.B.: We can call that “alternative distribution.” But when it does come out inNigeria and people hear it, will you be totally free and open to be interviewed and the press and radio?

S.K.: Yeah. Yes, of course. We did that this time.

S.B.: There are no restrictions on it?

S.K.: But the thing is the radio stations won’t play it too much. They won’t play it too much because most radio stations, like all other companies or so-called private business, are owned by government officials. In Nigeria, we don’t have a freedom of information bill here, where you can go to the minister of information and ask, “Okay, who is on the board of this company? What does this company do? Who is registered? Like you can find out any information here just by going to your Ministry of Information. It is important to do that in Nigeria because we want people to know that they own also, that they own everything that we think is investment, the so-called investment, the foreign investment. They lie. It is these men bringing back their money that they have stolen and stashed in London. So definitely, the radio stations will not want to play it often because it is not what the bosses want them to play. But I don’t care. My music and Afrobeat music has never been supported by the Nigerian government and it has been going on still forty years more. So I don’t think that is going to change, and I don’t think Afrobeat is going to change either.

S.B.: Matt wants to ask a question here. So Jay-Z and Will Smith came on board with FELA! recently. As producers, right? Or rather presenters. So Matt is wondering, have you met these guys? Have you hung out?

S.K.: No. I didn’t meet them. I missed the opening show.

Matt Payne: Okay, but do you think their participation is a sign that this is really being embraced by a pretty powerful sector of the American entertainment industry. The show is getting rave reviews and being incredibly well-received. How does that make you feel? Do you feel proud?

S.K.: Well, of course it makes me feel proud that everybody is involved in the show and everybody wants to be associated with what Fela stood for. Also I see there are black people as well, so I think they would have a lot of pride in knowing who my father was and what he did. Yeah, it is nice that they are there.

M.P.: Americans are finally turning their eyes and ears en masse to Fela. And so how does it feel that not only are reviewers and other famous musicians, but averageAmericans are really learning about Fela?

S.K.: And I think that would be what Fela is impressed by more. And me as well. That the people—not the famous people or the reviewers—but the people, because people are still people, here in America, that people will also feel what some people in Africa are feeling. Maybe not as much as in Africa, but they could relate. Those people should hear the message too. And Fela has never been able to get on the mainstream, and people have not found him because he never got on the radio. It was impossible to have Fela on the radio. Only a very small amount of DJs ever braved it and wasted half of their show playing one track. [Laughs] So now, there is a new way that Fela has been publicized and advertised to the world: not generally through the radio, but through pop culture, through word of mouth, through shows like this that put him in people’s minds, and through events. [MCA] Universal has done it for the last ten years. They have been giving him massive publicity. And now he is being carried forward by the producer of this play, the Knitting Factory, and all of these people.

S.B.: Can you say just a word about Steve Hendel, who has been a driving force behind this play from the start, and also the Knitting Factory releases?

S.K.: He is a really nice guy. Last year we had a good time at Central Park actually, after the concert. I met his lovely wife yesterday as well. When I first met him two years ago, I didn’t shake him strong enough. But when I met him last year, I gave him a firm handshake. To make up for the other time, I even gave him a second one. So I think Steve is just someone that is genuinely interested in my father’s message because he respects the music, and the message, and the man. And he has been able to use his influence to not bring Fela to the New York where a lot of people probably never ever, ever found out about who he was. Because he brought it to New York, and if he had said, “I want to produce a musical with African music…” “Stop, I have a meeting.” [Laughs] I think his idea is an incredibly original idea. Because things like this need a revolutionary idea, an idea that is totally out of the box. And I think FELA! on Broadway is totally that because… Broadway! This is bourgeois stuff. You know, Fela is not Broadway. So I think this is genius thinking, totally ingenious. And we should have come up with it. So I think with this step, Steve has given Afrobeat an incredible push, a push that cannot even be explained how great it is.

S.B.: Well said. And of course, another principle player in the whole success of FELA! is Bill T. Jones, the director and choreographer. Have you met him and sort of absorbed his work, and do you have some response to it?

S.K.: Now, you see, me, I was trained by the greatest dancer in the world. You know, all props to Mister Bill T.. I met him last year and he is an incredible guy. I saw him dancing on DVD, on the DVD of some of the rehearsals. Incredible guy and incredible choreographer. But you see, I was trained by Fela Kuti, who is the best dancer. So, I have not absorbed any of Mister Bill T’s work. But I love his work.

S.B.: I didn’t mean absorb in terms of take it on yourself, but kind of considered it and experienced it?

S.K.: I know. I have experienced it, but I didn’t absorb it. I enjoyed it. I’m trained, as I said, you know? This dancer that trained me, he is an angelic dancer when he is dancing. Me, I’m still…. Like Wu Tang Clan says, “Twenty six chambers.” I’m in the twenty-fourth chamber, approaching the twenty-fifth, of these dance moves. But it is incredible, he is really able to interpret it. Good interpretation. Because there were none of those cliché African dance steps, when everything and everyone you see is dancing in Africa… they have to do some weird, hand-throwing gestures. This is not African dance. So that is how I know Mister Bill T really did some research on how people in Africa really, at least Afrobeat people, dance and enjoy themselves. Because I started watching movies, and in every movie we talk like “this,” [affects phony African accent] and when we talk like “this”, we dance like “that”. Common misconceptions.

B.E.: Yeah, Bill T. Jones went deep. But Seun, we’ve seen you dance. And it is true, nobody up there is touching that.

S.K.: You know, I’m telling you. You see what I am saying? My coach was an incredible guy. That is all I can say. His name is Fela Kuti. I don’t know if you have heard of him. Incredible dude, too. You know, he had the moves too, man. You need to have seen this dude. He had the moves. [Laughs]

S.B.: One more thing I am interested in… In the play, when Fela was going to seek guidance about big decisions, he talked to the Orishas, the Yoruba deities. I am curious about how that resonates with Nigerians in general. Are they both Christian or Muslim and traditional? There is a line Fela has in the play…” What did the British bring to Nigeria? Gonorrhea and Jesus Christ.” When I heard that, I said, “Well, there goes the Baptist audience for this show.” [Laughs]. You were just talking about how there are churches instead of farms in rural Nigeria today. So what is the dynamic between Christianity and traditional African religion in Nigeria now?

S.K.: Well, you know, the churches are so powerful in Nigeria. These men all have private jets. They live like monarchs. They are all kings as well, in the name of God. They have kicked out the Catholics. Not kicked them out. The Catholics are still there. But these Pentecostal pastors, they have stolen all of their customers. I don’t call them a congregation. They are all “customers,” because they are paying money to these men. God. You know, God can do everything: heal the sick and move mountains. But he just can’t make money. Incredible. This guy gets by. But the main thing about Africa is that most people are in poverty. When you are poor, you are easily influenced. Everybody that is poor only wants to come up. And most of these pastors are also painting pictures of, “Okay, I was poor before the Lord came into my life. I live my life righteously and look at me today.” The part of it that he is leaving out of the story is, “Look at me today. I am just here telling you all of this while you are putting your money in my pocket. And I am getting rich.” So, Africans are religious. Most people actually don’t relate to Fela in Africa because he is not a Christian or a Muslim. And he is telling them that this is wrong.

B.E.: That’s pretty radical.

S.K.: Yeah. And these men are easily able to turn that and use it as a way to say, “If he is a good man, how come he does not believe in God? In our white God?” So that is how most people pushed off his message in Africa. But at the same time, even more people realized that he is the genuine thing, and respect us for that.

B.E.: We have been doing some research on the Nollywood film industry recently. And I realized that a lot of those films are made by the Pentecostal churches and funded by them. They seem to put African traditional music and religion in a very bad light.

S.K.: In a bad light? Yeah, of course.

B.E.: That was kind of shocking to me, actually.

S.K.: You were able to investigate that, man? That is cool because I have been trying to tell people for years that. “Why do you think all of the movies in Nigeria are about churches?” Every time somebody will be suffering because somebody is doing juju, the bad African gods. Then Jesus Christ comes at the end and sets them free. It is crazy. Absolute bull***t. Ninety-eight percent of all the movies have that story line. Trust me.

B.E.: So you don’t like Nollywood movies.

S.K.: Me? Hollywood hardly impresses me. So how can Nollywood impress me at all? Before I can watch a good Hollywood movie, they do thirty movies before I find a movie I can watch. So Nollywood has to do maybe three-thousand before I find one I can watch. [Laughs]

S.B.: What about Bollywood?

S.K.: No, man. Too much dancing. They are all like High School Musical. There is only music in Bollywood. Before they do anything… [starts impersonating Bollywood dancers, and laughs] Suddenly everybody on the streets just dances around, and it is a musical. [Laughs] You know, it is nice. Most people get entertained by this. But I am a musician. I get entertained in other ways. I like my reggae music. When I hear some reggae album, it is like watching a movie. It takes like an hour to listen to a whole album anyway. About an-hour-and-a-half, which is the same as a movie. I like music more than I like movies.

B.E.: So what is an example of a movie that you do like?

S.K.: I love The Lord of the Rings. That has to be my favorite movie: one, two, and three. Matrix is sh**, except the first one. You know, those guys…. Because after the first one, I was looking forward to a good two and three, and because that woman died, they tried to change the story. Why couldn’t they just tell everybody that the woman died, we are going to get a new actress, and just put her in place of the oracle? You understand? But they are not trying to explain why the oracle has to change. And, oh my God… I know that the Matrix did not have a book before. The story was original, so that threw me off. I don’t like the soundtrack for the end because they use this rock band for the first one and I thought they were going to use them for the last one. They have this song called “Freedom”. What is the name of this band?

M.P.: Rage Against the Machine.

S.K.: Yeah. They had a song called “Freedom”. And I thought that “Freedom” was going to be the soundtrack for the last film as well, but they used that… accchh…Anyway, they broke my heart, The Matrix. But I love The Lord of the Rings. I am a huge, huge standup fan. I watch a lot of standup DVDs. I love comedies, and a few action movies. I like watching good action movies, not any Arnold “one man kill all”. If I want to watch “one man kill all,” I watch Jet Li. That is a more interesting “one man kill all”. More hand-to-hand, less gun-to-mouth. [Laughs]

B.E.: I hear you. Did you get to see District Nine?

S.K.: Yeah, yeah. I saw District Nine. I don’t know what all the fuss is about. It is a great movie. You know, that is what I don’t like about Nigerians. Everybody is suddenly saying that Nigerians are being depicted as bad people in the movie, but it’s a movie, man. Do you know why Nigerian ambassadors and government were against the movie? Because what the movie was saying was true. That is the reason why. If people get pissed about what a movie says about your people, then the Italian government should be releasing a statement against America every two weeks. Because every time I watch an American film with an Italian guy in it, he is in the mob. He might be a good guy in the beginning or something, but then you see he is in the mob. I am not supposed to now believe that every Italian guy is in the mob.

B.E.: Yeah. Well, there are actually people complaining about that.

S.K.: But, you know, it is just a movie. All black people are either rappers or drug dealers. They are not rapping in the movie or doing some sort of acting or singing. You know, we are the creative guys. If we are not doing that, the guy is a criminal. The criminal good guy. I will see if there is anything like that, but hey, there are good black people in movies. In fact, the Nigerian community in South Africa, going by what the South African government releases through statement and fact, commit a lot of crimes in South Africa. Lots and lots and lots of crime committed in South Africa by Nigerians.

B.E.: They are having a hard time down there. There was an article in the paper just today about it, about foreigners, Africans, getting beaten up in South Africa.

S.K.: Yeah. So, it goes both ways. South Africans make a movie and talk about Nigerians because Nigerians and South Africans are given that impression. And basically the government will complain because if any logical person is going to pass blame, you pass blame on the government of Nigeria. South Africa is a country that is way younger than Nigeria. When Nigeria was reached, South Africa was not even existing properly. They were under apartheid. apartheid ruled. So, to have a country like that to come out of apartheid rule and be more advanced than most, so advanced that our youth run there because they don’t have the right qualifications from Nigeria in the first place. They have to resort to crime to survive there.

It is a shame on our government, and they should stop blaming some movie producer that is trying to make some bucks, legitimately. You are there sitting in your office, stealing money that is supposed to be used to build schools that will train kids to better our own country and build great businesses to employ people. Instead of trying to change your ways, you are blaming movie producers for making one movie in South Africa. It is not even in Hollywood. It is South Africa. I love District Nine. I saw the movie twice, even if it didn’t make any sense at the end. I just saw it twice to piss the government guys off. In my own little room, I said “I am seeing it again.” [Laughs]

B.E.: That is great. Thanks a lot, Seun. It was really great to talk with you.

S.K.: It was nice talking to you guys too.

For more information, visit www.FELAonBROADWAY.com.

B.E.: Misconception. And they printed that in the New Yorker too. They are supposed to be careful up there. But anyway, a little bit more about the play and the way it tells your father’s story. You said that it was a bit dramatized. What do you mean by that?

S.K.: Yeah, of course, it’s a play. So that is exactly what I mean. It is dramatized. It has to be interesting. But the story stayed the same, and that is important. Some of the stage acts, for example. Fela did not have people flipping on stage, but on Broadway it has to be done to make the show lively and interesting. For me, I went to the show and I was hugely impressed. You don’t expect it to be exactly how it is. It’s a play. That is exactly what I meant by the extra drama that was put in there. And I appreciated that because it is extra effort trying to make it beautiful.

B.E.: The play summarizes aspects of his life very, very quickly. There is that section that talks about how he created Afrobeat. In five minutes, you have highlife, traditional African drumming, jazz and James Brown. All of this stuff, and then it arrives at Afrobeat. What did you think of that section, speaking as a musician?

S.K.: For me, it is the story being told. That is what is most important. That is the question I asked. And you know, even if it is five or ten minutes, I mean, as long as the proper message is being put across. Afrobeat was influenced by all of these genres. In his autobiography, he said it already, and to most people that influenced my father, that is not a surprise. Even if it takes them one minute to do it, as long as they tell the right story, which they did, how long it took is not that important I guess.

B.E.: Yeah, it is actually very powerful. A lot of people who see this play don’t know your father’s story. And the way they do it where they hear all of this music, and then you hear Afrobeat; it is very revealilng actually. I think people who would have no idea, and I’ve never really seen it presented quite that efficiently. You know what I mean?

S.K.: Yeah, well, on Broadway you mean?

B.E.: Yeah, I was just impressed by that segment. I also really find very interesting the part that deals with Sandra Isadore, where he is arguing about racial politics in America as opposed to in Nigeria in the 1970s. That was before your time, but did that ring true to you, that section with Sandra?

S.K.: Yeah, of course because I grew up with my dad and I understand his life story from a personal point of view. And before he met Sandra, he was just like every other African young man who didn’t read much into African history. He just took conventional wisdom as truth, just the way people take the conventional wisdom that he is wearing pants on stage as true. It is just conventional wisdom. So back then in Africa, people used to think that Africans were in the bush. You know, they didn’t understand African history. But the African Americans here who didn’t have a connection to home, the only thing they could hold on to was the history and they knew the history of black people, which Sandra opened his eyes to. It said black people have been great before, which was something that was not taught back home.

Even up to now, I cannot say that I studied any relevant thing about the history of my people in school. Everything that I have learned about Africa I have learned independently, not from our educational system. It just touches a few irrelevant topics about the history of Nigeria, not even Africa. Nothing gives African youths today a sense of pride in who we are, even up to today. It is interesting that people know that it was Sandra that gave my dad that knowledge of being able to understand how great his people are, and to see that black people have done great things. It is not that we are just monkeys that white people came to train, like pet animals and brought us civilization. We were civilized before. They brought us their own kind of civilization. So, I think in that aspect, the story was told because that was what really happened. As I said, it has to be dramatized. I don’t see anything wrong with the way the story was told as long as the message is passed across: that Sandra taught him something about Africa. It’s a fact.

B.E.: So you probably got a better history education at home than you did at school.

S.K.: Well, yes, and even independently and as a young child I wanted to know more because I always realized that Nigerian education was boring. So I have always been learning from a very young age independently of education. You know, education is not learning. Most people mistake education for learning; it is two different things.

Sean Barlow: A big part of Fela on Broadway is the story of your father facing down the authorities, facing down the regime, facing down the dictators of his time, and suffering for it, of course. I know you in your songs have also been critical of the powers that be in Africa. You are continuing your father’s critique of power. But what has changed since Fela’s time?

S.K.: Not a lot has changed in Africa between the 70s and today. I always say to people, the way that Africa has developed has shown really that slavery has not ended in Africa. As time has progressed, the poor have gotten poorer and the rich have gotten richer, and fewer in number because in Africa today rich people are like a monarchy; they marry only rich people, they do only things among themselves. It is very detached from the common man. The elites are the elites. Nobody cares about what is happening to the man on the streets. In Africa today, I don’t see a lot of development from the aspect of the civilians or citizens. There is a lot of development for the industrial aspect, the money making part of Africa: telecommunications, construction, oil. These money making industries, for government officials, are well-developed.

They have big buildings and ultra-modern equipment, and they work. But the things for the common man, human rights, water, light, food, education, healthcare. What the people need are the things that are lacking in Africa today. I know a lot of expatriates in Nigeria who work for oil companies that tell me that they never want to leave Nigeria because they have never had so much fun in a place and it is so nice making as much money as they are making. So, it is how it is in Nigeria. That is a picture of what is going on everywhere in Africa, not only in Nigeria. Everywhere there is development, it is only development of commerce, it is money-making development. I have not seen any concrete development. Because the real development that matters is investment in the people. No company comes to Africa to invest in the people. Everybody comes to invest in some kind of business. Even when actors and actresses come and adopt a baby and spend five thousand dollars on the pipeline, the only thing that it does is show for the government as well as government sponsors maybe a month later when they are earning two-hundred-thousand, five-hundred-thousand dollars for one gig. So for me it is not investing in a cause, and the government is not investing in a future for the people of Africa. So that is that.

B.E.: Let me ask you about the role and the status of Afrobeat music today in Nigeria. When we talked two years ago you told me about how it was a difficult situation where you had a very loyal fan base but you did not have a lot of support from media and government. What is it like now?

S.K.: It is still the same, still the same. That is never going to change. I don’t see Afrobeat in Africa ever being sponsored by any corporate body or supported by any government parastatal. That is what makes sense. That is what makes sense because it would be crazy if the government is suddenly helping Afrobeat and all companies are sponsoring Afrobeat. Then there is something wrong. Probably activism has stopped, and now we are seeing the interest in it. I guess if I get a call from a government person offering me sponsorship, I would have to review all of my lyrics again. What did I just say? Did I just say something where I could be misconstrued? Support! So, this is where it is. For me, if you are an activist, you cannot mourn about things like this. Every job has its dangers. It is one of the things you go into knowing this is the caution and this is what is going to happen. And you can’t keep mourning about it. I am not as rich as I would like to be, compared to my talents. Because I see a lot of artists in Nigeria that don’t have a tenth of what I got, going “Mh, Mh, Mh, Mh, Mh, Mh, Mh”, making all of the money because that is what is being promoted. But for me that is not what matters. What matters is the message. My father as well had contemporaries in his time that made a lot of money and that had a lot more money than him, even today. But they are never going to have their life story told on Broadway.

B.E.: Do you think it’s at all uncomfortable for officials of the Nigerian government to have Fela arrive on Broadway? I mean regardless of what you think of his politics, he is a Nigerian artist who is being recognized in one of the highest cultural venues in the world. You have to feel an element of pride. How do you think it makes officials feel to have this recognition for Fela?

S.K: Should I tell you the truth? The truth is that they actually believe it is not happening. You know, if you don’t really want to see something, you can make yourself believe it is not there. Maybe they would come and not even know it is there. They would come in a non-official capacity. Definitely a lot of Nigerian officials would have come here, without seeing the play. That is how they are. Our state is Lagos state, which is not in the federal party. So their policies are very different from the federal policy. Federal officials would not be caught dead in an official capacity at a Fela event. They want a good future, and the federal government is still stealing money. So, I don’t think they would support Fela in public.

B.E.: Even on Broadway?

S.K.: Even on Broadway. They don’t care about Broadway. What is Broadway? They don’t care about anything. These African rulers, all they care about is where the next big bag of dollars is coming from. They don’t care about anybody, anything.

B.E.: But isn’t it possible that bags of dollars could come from having one of their artists being recognized this way? If they thought about it the right way..

S.K.: But he is not one of the approved artists. You have to understand; that is how it is. If it was Sunny [King Sunny Ade] and his life on Broadway, trust me they would be there. All of them, happy as hell. So if you want to get them there, just do a show on Sunny. They’ll be there.

B.E.: I spoke with your sister Yeni about it when she was here a month ago. Like you, she loved the show, but after we had finished our interview, she said to me, “Well, there was one thing that wasn’t right about that play. And that was the fact that right at the beginning of the play, Fela says that he is planning to leave Nigeria.” Yeni said to me, “Fela would never leave Nigeria.”

S.K.: Fela left Nigeria. He had put himself into self-exile. Maybe she has forgotten that he went to Ghana. Fela would not leave Africa, but he left Nigeria for awhile. In fact, he did not want to come back. The Ghanaian government deported him because he was already inciting the Ghanaian students. Just less than a year he was there. He was already giving them hell as well. I think he was Ghana between ’78 and ’79.

B.E.: So that was after the raid, just the way it is in the play.

S.K.: Yeah. It was in the book. Have you guys read the book?

B.E.: Well, yeah, absolutely.

S.K.: Not the choreographer’s book, but Fela’s autobiography by Carlos Moore.

B.E.: Carlos Moore. Yeah, I have it.

S.K.: This Bitch of a Life. I know you are not the New Yorker, but do your research. F***in’ hell.

B.E.: No, I just wanted to hear it from you.

S.K.: Okay, if you put it that way. George Bush! You just George Bush-ed it right now. [Laughs] I knew it, I knew it, I knew you were all bums. You just wanted to get the evil guy out. [Laughs]

B.E.: Let me ask you this about the play. I feel that everything you see about Fela on the stage there feels very true. It feels true to everything that I’ve read about him, and I saw him perform a number of times. But I think that there are some things about him that you don’t see in the play. And I was talking to Yeni about this as well. There is a tough side to Fela, the way he was with his musicians, for example. You were with the band a lot; you know very well what it was like. Talk to me about things that you remember about Fela that were sort of beyond the scope of the man we see on the Broadway stage.

S.K.: Well, the thing is, it is impossible for them… I’ll be open about this, I don’t think they had the right consultation team for the play. You know, the people they had with them, I’ll say it anytime, were guys that just made money from Fela and were never really close to him, never really knew him, never stayed with him for longer than ten years at a particular time. And there are people alive today that stayed with Fela for thirty years. Sorry. Some of them are in my band now for forty years. But what I am saying, they knew thirty years of his life. There are women that are still alive that lived with him for twenty years of his own life. There are people like that that knew him very well, that were never consulted. They were all of these people that he actually stopped talking to because they betrayed him and they left him. They were the ones brought together to this place. They are only human. They must have lost touch with a lot of little things about him. And at the same time, I said the play is for drama. People always have to remember that. A play is about drama, and it is to bring out the best side of everything, the full side of everything. In the little I know, if showing that toughness is not assisting the story in any way, there is no way they were going to use it, even if they knew about it.

B.E.: So what would you say is important to know about Fela that is not in that play?

S.K.: I think the only thing, if anybody ever read my forward to this play, because I did a little write-up introduction to the play… If anybody ever read my part, I said, “Fela’s life and struggle has always been about the elevation of the common man in Africa and the betterment of his future.” Any way Fela is portrayed, that is the message that is carried on there because his music will be celebrated and his message will be put across. So for me, what is ultimate about this play is not what is in it or what is not in it. It is what people that are now open to Fela will have to live with. They will live with the fact that now they will want to know about this man and to understand his struggle. I know people will be involved in the movement of the people. You understand what I am saying. So for me, it is not about how well they were able to do it. The success of the play for me is Fela’s message is understood by more people that would never had had the chance to understand him if it was not brought to this place. For me, it is all about the growth of the movement, and I see this as a big step in the growth of the movement. Sahr and the producers said, “If Fela was alive, we probably would not be able to do this play.” If he was alive, they would probably not get the permission to do a play like this. Never.

B.E. and S.B.: Why?

S.K.: Because first of all, he would never agree for his music to be shortened while they are trying to do the play. He would say, “If they are going to do it, why aren’t they playing those Mozart songs? I did that piece for four hours. That is what you are going to do. You are going to play my song the way it is written, every time.” That is him, you know. For him, his Afrobeat… There is another misconception. When I read the story, it says that Motown gave him a deal that he turned down for the spirits. Then he changed his mind, and went back to Motown. But then Motown had already found Femi, and Motown turned him down. Fela never changed his mind about Motown. He never went back. He turned them down. They gave him a-million dollars, and he said no. He never went back to say yes. They stayed with him in Lagos for a few days trying to get him, but they couldn’t. And there was a guy called Mikel Avantario that brought this guy; he was a friend. And so he took them, because he didn’t want to leave empty handed, so he took them to see my brother. And after that Motown collapsed a few months after. Which when I was saying at the Shrine, you see, the Gods were not wrong for telling him not to sign with them. If he had signed with them, they would have collapsed a few months later and all of his stuff would be, you know, gone.

B.E.: So he didn’t sign. Was it because they wanted to interfere artistically or they wanted him to shorten his songs?

S.K.: No, he just told them no because the spirits said, “No”. And he was really serious, and he said he couldn’t do it with them because he consulted his gods and they didn’t want him to do it. That was the reason he gave, and he never went back on it. So, I don’t like it when I read, and they make him look like this crazy man that talks to spirits and goes back to try and get the money and they turn him down. He was never that kind of guy.

B.E.: Well, I think that you are right, that the play doesn’t get into anything like that. What you come away with is the message.

S.K.: Yes. And I think that is what is most important. Because for Fela, Afrobeat was not just music, it was like his baby so he didn’t want to give it away. He didn’t want it to be compromised because he felt like if you said, “I want to take ten minutes off,” it was like cutting off his baby’s leg. For him, it was really personal. That is why I was thinking that this play could never have been held because Fela would be like, “If they want to do a play on my life they should call it ‘My beat in Nigeria’.” Even if they call it “My beat on Broadway.” And when he sees that it convolutes his seventeen group orchestra playing, maybe he will want to act himself. [Laughs]

S.B.: That raises an interesting question. What do you think your fans and Femi’s fans would think if they brought this Broadway production to the New Africa Shrine in Lagos? What would be the reaction?

S.K.: It would be great. It would be great. And I think a lot of people would come through to see it as well.

S.B.: When you first saw Antibalas performing on stage as the people were streaming into the theater and you heard them throughout the play, what did you think of Antibalas?

S.K.: They are good, but I have to disagree with Questlove, as he calls Antibalas the best Afrobeat band. Maybe they are the best Afrobeat band in New York. [Laughs] But they are a tight band. I have jammed with them before, and I have known them for a long time. And I think they are good enough for the play. But they are not the best.

B.E.: Who do you think is the best? Well, I guess we know, don’t we?

S.K.: I am. [Laughs] I have got the best band, you know. Definitely.

B.E.: Okay. Who is the second best?

S.K.: I don’t know. I don’t deal in seconds.

B.E.: Fair enough. But here is one second you might deal with: your second record. Can you give us a preview?

S.K.: Alright. Well, you know, the second record becomes the first because it is going to be the newest one. We are going to record soon. I am really excited. I am practicing, and we are still rehearsing the songs though with the band. It has been a really tough these past two years—going everywhere. We don’t have time. We had only worked on maybe thirty percent of the songs on the album. Then this summer we played a worldwide tour. So finally we have been home for the last three months, and we have been working and are seventy percent done, which is a huge leap in three months compared to the thirty percent that we did in a year, basically.

B.E.: Anything to preview about what is going to be different, what is going to be new, some of the things you are going to talk about?

S.K.: Well, for me, what we talk about is Africa, every time with Afrobeat. Afrobeat is about the development of Africa properly. Not industrial development. You have to get the foundation and the basics set. It is the African people that can carry Africa. Even if the African people are weak, what strength can they use to carry Africa? So right now we have an Africa that is being carried by Europe and America, on aid, so-called aid that is actually kickbacks for being able to exploit the continent. They have been giving aid to Africa since the 70s, and they have been increasing by two-hundred percent almost every year. And the suffering in Africa has also been increasing by two-hundred percent every year. So, I think with this aid and the suffering, we have something together. The more aid we get, the more our suffering is in Africa. It is important for people to think like this to realize and think outside of the box. Don’t see these handouts as free handouts. The more our government claims that we are getting help from IMF, UNESCO, Paris Club, Monsanto, and all these companies, the more people are suffering.

The Monsanto issue is the worst issue. Since Monsanto has come to Africa, food prices have… I can’t even explain how high. There is no percentage, maybe one-thousand percent. That is how much food has increased in Nigeria in the last five years alone. These farmers are poor already. Now you are making them pay for the seeds that they even use to plant the food. You know, more costs. They don’t have the right transportation; most of the food is rotten before it can even get to the market because they don’t have the right storage. So the few items that can get to the market, it is sold at… You can’t store this f***ing GMO food. It has expiration dates. They spoil in less than four of five months if they are not consumed. Not to talk of the diseases they cause, how much it costs for the pesticides, and the diseases the pesticides still cause in all of Africa. But the government, because they still need the aid from UNAID, they will put pressure on the government to make sure that the farmers are forced to use this product. Then, they will make people pay huge amounts of money for food, and then they will blame it on something else. Oh, there is war somewhere. That is why food can’t get there.

The way Africa is, it is shame for our governments in Africa to sit there looking for money to feed five hundred thousand people in Sudan. What is the meaning of that rubbish? Africa is full of land. Why can’t we grow food? People were growing food before the white man arrived, and we were eating. So now how come we can’t eat? I don’t think there are more people in Africa than arable land. I don’t think so. Africa is not that developed. Everywhere there is arable land still. Even in Nigeria, as developed as Nigeria is, if you travel by the roadside, you will see what I mean. Where is developed? Everywhere is just forests that can be converted, at least bits of it. In Europe and America when you are traveling the country road, everywhere there is farmland, feeding the people. In Africa you see churches, huge churches. People plant feet instead of seeds in those places.

S.B.: I have a follow up question on the new album. When is it going to come out?

S.K.: We hope next summer.

S.B.: And it comes out in Nigeria first?

S.K.: No, no. Nigeria last, every time. If I bring it out in Nigeria first, I might as well not have any release anywhere. Those pirates would just help me do a worldwide release. They would be like, “Look, Seun Kuti, he released it here. Just, don’t worry. We will do the rest.” [Laughs]

S.B.: We can call that “alternative distribution.” But when it does come out inNigeria and people hear it, will you be totally free and open to be interviewed and the press and radio?

S.K.: Yeah. Yes, of course. We did that this time.

S.B.: There are no restrictions on it?

S.K.: But the thing is the radio stations won’t play it too much. They won’t play it too much because most radio stations, like all other companies or so-called private business, are owned by government officials. In Nigeria, we don’t have a freedom of information bill here, where you can go to the minister of information and ask, “Okay, who is on the board of this company? What does this company do? Who is registered? Like you can find out any information here just by going to your Ministry of Information. It is important to do that in Nigeria because we want people to know that they own also, that they own everything that we think is investment, the so-called investment, the foreign investment. They lie. It is these men bringing back their money that they have stolen and stashed in London. So definitely, the radio stations will not want to play it often because it is not what the bosses want them to play. But I don’t care. My music and Afrobeat music has never been supported by the Nigerian government and it has been going on still forty years more. So I don’t think that is going to change, and I don’t think Afrobeat is going to change either.

S.B.: Matt wants to ask a question here. So Jay-Z and Will Smith came on board with FELA! recently. As producers, right? Or rather presenters. So Matt is wondering, have you met these guys? Have you hung out?

S.K.: No. I didn’t meet them. I missed the opening show.

Matt Payne: Okay, but do you think their participation is a sign that this is really being embraced by a pretty powerful sector of the American entertainment industry. The show is getting rave reviews and being incredibly well-received. How does that make you feel? Do you feel proud?

S.K.: Well, of course it makes me feel proud that everybody is involved in the show and everybody wants to be associated with what Fela stood for. Also I see there are black people as well, so I think they would have a lot of pride in knowing who my father was and what he did. Yeah, it is nice that they are there.

M.P.: Americans are finally turning their eyes and ears en masse to Fela. And so how does it feel that not only are reviewers and other famous musicians, but averageAmericans are really learning about Fela?

S.K.: And I think that would be what Fela is impressed by more. And me as well. That the people—not the famous people or the reviewers—but the people, because people are still people, here in America, that people will also feel what some people in Africa are feeling. Maybe not as much as in Africa, but they could relate. Those people should hear the message too. And Fela has never been able to get on the mainstream, and people have not found him because he never got on the radio. It was impossible to have Fela on the radio. Only a very small amount of DJs ever braved it and wasted half of their show playing one track. [Laughs] So now, there is a new way that Fela has been publicized and advertised to the world: not generally through the radio, but through pop culture, through word of mouth, through shows like this that put him in people’s minds, and through events. [MCA] Universal has done it for the last ten years. They have been giving him massive publicity. And now he is being carried forward by the producer of this play, the Knitting Factory, and all of these people.

S.B.: Can you say just a word about Steve Hendel, who has been a driving force behind this play from the start, and also the Knitting Factory releases?

S.K.: He is a really nice guy. Last year we had a good time at Central Park actually, after the concert. I met his lovely wife yesterday as well. When I first met him two years ago, I didn’t shake him strong enough. But when I met him last year, I gave him a firm handshake. To make up for the other time, I even gave him a second one. So I think Steve is just someone that is genuinely interested in my father’s message because he respects the music, and the message, and the man. And he has been able to use his influence to not bring Fela to the New York where a lot of people probably never ever, ever found out about who he was. Because he brought it to New York, and if he had said, “I want to produce a musical with African music…” “Stop, I have a meeting.” [Laughs] I think his idea is an incredibly original idea. Because things like this need a revolutionary idea, an idea that is totally out of the box. And I think FELA! on Broadway is totally that because… Broadway! This is bourgeois stuff. You know, Fela is not Broadway. So I think this is genius thinking, totally ingenious. And we should have come up with it. So I think with this step, Steve has given Afrobeat an incredible push, a push that cannot even be explained how great it is.

S.B.: Well said. And of course, another principle player in the whole success of FELA! is Bill T. Jones, the director and choreographer. Have you met him and sort of absorbed his work, and do you have some response to it?

S.K.: Now, you see, me, I was trained by the greatest dancer in the world. You know, all props to Mister Bill T.. I met him last year and he is an incredible guy. I saw him dancing on DVD, on the DVD of some of the rehearsals. Incredible guy and incredible choreographer. But you see, I was trained by Fela Kuti, who is the best dancer. So, I have not absorbed any of Mister Bill T’s work. But I love his work.

S.B.: I didn’t mean absorb in terms of take it on yourself, but kind of considered it and experienced it?

S.K.: I know. I have experienced it, but I didn’t absorb it. I enjoyed it. I’m trained, as I said, you know? This dancer that trained me, he is an angelic dancer when he is dancing. Me, I’m still…. Like Wu Tang Clan says, “Twenty six chambers.” I’m in the twenty-fourth chamber, approaching the twenty-fifth, of these dance moves. But it is incredible, he is really able to interpret it. Good interpretation. Because there were none of those cliché African dance steps, when everything and everyone you see is dancing in Africa… they have to do some weird, hand-throwing gestures. This is not African dance. So that is how I know Mister Bill T really did some research on how people in Africa really, at least Afrobeat people, dance and enjoy themselves. Because I started watching movies, and in every movie we talk like “this,” [affects phony African accent] and when we talk like “this”, we dance like “that”. Common misconceptions.

B.E.: Yeah, Bill T. Jones went deep. But Seun, we’ve seen you dance. And it is true, nobody up there is touching that.

S.K.: You know, I’m telling you. You see what I am saying? My coach was an incredible guy. That is all I can say. His name is Fela Kuti. I don’t know if you have heard of him. Incredible dude, too. You know, he had the moves too, man. You need to have seen this dude. He had the moves. [Laughs]

S.B.: One more thing I am interested in… In the play, when Fela was going to seek guidance about big decisions, he talked to the Orishas, the Yoruba deities. I am curious about how that resonates with Nigerians in general. Are they both Christian or Muslim and traditional? There is a line Fela has in the play…” What did the British bring to Nigeria? Gonorrhea and Jesus Christ.” When I heard that, I said, “Well, there goes the Baptist audience for this show.” [Laughs]. You were just talking about how there are churches instead of farms in rural Nigeria today. So what is the dynamic between Christianity and traditional African religion in Nigeria now?

S.K.: Well, you know, the churches are so powerful in Nigeria. These men all have private jets. They live like monarchs. They are all kings as well, in the name of God. They have kicked out the Catholics. Not kicked them out. The Catholics are still there. But these Pentecostal pastors, they have stolen all of their customers. I don’t call them a congregation. They are all “customers,” because they are paying money to these men. God. You know, God can do everything: heal the sick and move mountains. But he just can’t make money. Incredible. This guy gets by. But the main thing about Africa is that most people are in poverty. When you are poor, you are easily influenced. Everybody that is poor only wants to come up. And most of these pastors are also painting pictures of, “Okay, I was poor before the Lord came into my life. I live my life righteously and look at me today.” The part of it that he is leaving out of the story is, “Look at me today. I am just here telling you all of this while you are putting your money in my pocket. And I am getting rich.” So, Africans are religious. Most people actually don’t relate to Fela in Africa because he is not a Christian or a Muslim. And he is telling them that this is wrong.

B.E.: That’s pretty radical.

S.K.: Yeah. And these men are easily able to turn that and use it as a way to say, “If he is a good man, how come he does not believe in God? In our white God?” So that is how most people pushed off his message in Africa. But at the same time, even more people realized that he is the genuine thing, and respect us for that.

B.E.: We have been doing some research on the Nollywood film industry recently. And I realized that a lot of those films are made by the Pentecostal churches and funded by them. They seem to put African traditional music and religion in a very bad light.

S.K.: In a bad light? Yeah, of course.

B.E.: That was kind of shocking to me, actually.

S.K.: You were able to investigate that, man? That is cool because I have been trying to tell people for years that. “Why do you think all of the movies in Nigeria are about churches?” Every time somebody will be suffering because somebody is doing juju, the bad African gods. Then Jesus Christ comes at the end and sets them free. It is crazy. Absolute bull***t. Ninety-eight percent of all the movies have that story line. Trust me.

B.E.: So you don’t like Nollywood movies.