September 5, 2012 Bayreuth / New York (via Skype)

Guest scholar Stefanie Alisch was doing dissertation research in Luanda while I was there, finishing up a three-month stay of living the kuduro life and swatting mosquitoes in the popular neighborhood Chicala Um. She knew the ropes better than me, and took me on my first (but not my last) candongueiro ride (see below).

Stefanie is one of an emerging wave of DJ-musicologists. She deejays under the name Stef the Cat. She came up deejaying in the Berlin post-wall party scene, while she ran a bar in an apartment and commuted to Dublin for a monthly DJ residency, deejayed in a number of European countries, then spent a year in Brazil, where she threw parties. She’s not a party animal herself, though. She’s very focused, returns text messages immediately, speaks excellent Portuguese, and this year in Luanda she co-organized the first-ever kuduro conference, where she deejayed at the afterparty.

Ned Sublette: Who are you and what were you doing in Luanda?

Stefanie Alisch: My name is Stefanie Alisch. I’m a musicologist and DJ from Berlin. I now live between Berlin and Bayreuth, and I am presently affiliated with the Bayreuth International Graduate School of African Studies, and I’m also the founder of the Groove Research Institute, Berlin, so I’m always affiliated to at least two institutions. [laughs]

I went to Luanda this year for three months to continue my field research on kuduro and, more specifically, kuduro dance. Last year I went for a month and this year I went for three months, from the beginning of May till the beginning of August.

NS: What is kuduro?

SA: Kuduro is electronic music from Angola and the Angolan diaspora, and when I say music, I mean music in the widest sense, including dance, media and distribution, all wrapped in one.

NS: What are the various creation myths of kuduro?

SA: Well, last year one of kuduro’s media gate-keepers, and he’s also usually credited as one of the founders, Sebém, organized a concert that was celebrating fifteen years of kuduro. So if we say the year 1996 as the starting point, it now has about sixteen years as a style. Even though this has to be – I think the foundation myth has to be complicated, a little bit. Because kuduro started to accumulate in Luanda in the early 90s, when people went to discotheques such as the Banca [or] Pandemonio to listen to electronic music, which was Chicago house but also Eurodance the DJs were playing, with vinyl records. MCs were MCing in the sense of being a master of ceremonies, holding the night together, hyping up the crowd and the dancers, and dancers came on stage to show their dance moves. And the dance moves had specific names such as Gato Preto [Black Cat], Açucar [Sugar], Kassumuna, Bungula. And then in 1996 the dancer and MC Tony Amado released a song called “Amba Kuduro Mamá,” which means dance the stiff bottom, mama, and that name stuck. And it turns into the name of the genre.

NS: He’s always spoken of as a founding kudurista . . .

SA: Tony Amado is very present, but he keeps saying that he’s the inventor of kuduro, which doesn’t really make sense, because it’s such a big genre, and such a multifaceted genre. There are Marcus Falcão and Luís Esteves, who were DJs and owners of the record company – Luís Esteves was a DJ and partner in RMS, Marcus Falcão was a partner in the RMS record company, and they recorded, according to their creation myth, the first kuduro record, which was recorded in Spain.

NS: Everyone seems to concur that it came out of the discos in the paved downtown of Luanda.

SA: This is what Marcus Falcão says. He used to own the Pandemonio, and they saw this new style emerging. Luís Esteves, who used to be a DJ who was playing Chicago house, electronic music, at these discotheques in downtown Luanda, at the kuduro conference said to Tony Amado, “you were MC-ing over the tracks that I was playing at the time, so don’t say that you invented the genre, because you were MC-ing and singing, and doing crowd animation over the electronic music that I was DJ-ing at the time, so you can’t put yourself as the inventor.”

Luís Esteves went on to say that his record company, RMS, released the first kuduro record, by Bruno de Castro, and in a later interview, his partner in the record company, Marcus Falcão, told me that he went to Spain with Bruno de Castro with the pre-recorded tracks, and went to Madrid and recorded things in studio with live musicians, playing keyboards, drums, and whatnot. And that album was called No Fear, by Bruno de Castro, and that’s the version that Marcus Falcão and Luis Esteves are putting forward.

NS: I was struck by what you said about the Angolan diaspora being part of kuduro. . .

SA: I think it’s very interesting to see that the diaspora is so important. Not only was the Bruno de Castro album recorded in Spain, Tony Amado also recorded his first album in Boston. And Sebém lived in Portugal, or between Portugal and Luanda in the 1990s, and apparently he was an MC at raves in Portugal, and that’s where he picked up the practice of throwing techno-parties. That’s where he got to know this style of partying, and he MC-ed in Luanda as well at raves, but also at his radio show, which – people give me different information, some people say it was every Saturday night at 5 or 6 o’clock for thirty minutes, some people say it was daily, but information seems to gravitate toward Saturday night at 5:30, something like that. I think it was Radio LAC (Luanda Antena Comercial).

NS: Tell me about the radio scene.

SA: There is the national radio building that also has the TV station in it. It has a record archive, it broadcasts in various national languages. That’s the national TV. Then there’s what’s called Radio Escola at the CEFOJOR, which is the center for journalistic training, which broadcasts all over Luanda, and there’s also Radio LAC, which is Luanda Antena Comercial. And there’s also, very interestingly, Radio Viana, which has a small studio, just one room, Radio Viana has a program called “rompimento,” which is like, “the smashing,” this programme, moderated by Luís Candeias, plays a lot of popular music, and also includes kuduro.

It’s interesting: there’s national radio, there’s Luanda radio, and then there’s also radio for certain parts of Luanda. And then there’s also Radio Ecclesia, which officially belongs to the Vatican, and it also has some various interesting – it’s next to the Cathedral as well, where we stood at the corner.

Remember the corner where we were standing and you were taking pictures, and I said, “tone it down because the police are coming?” We were standing next to the Vatican-owned radio, that’s the Radio Ecclesia. They have very interesting programs on African music like “Afribantu” . . .

NS: Back to Sebém . . .

SA: Sebém is an MC gifted beyond imagination. He has a very flamboyant way of dressing, he’s a very vibrant, interesting presenter because he – have you ever watched any of the TV shows that he presented? Every other week his hair would be pink, or blond, or blue. He would wear a Mohawk haircut, or anything. The next day – he used to from 2009 until December last year he presented the first ever TV show about kuduro, called Sempre a Subir, and every week he would rock up in the most amazingly flamboyant outfits – big pink scarfs, or camouflage, or anything you could imagine. Totally camp. Big flowery prints, whatever [laughs].

He had a key role in selecting people who would come on this program, so he was a media gatekeeper for this program, and I could witness one event that I already mentioned, Kuduro Não Para in Cidadela Stadium last year in August, where he organized a football [i.e., soccer] game in the morning and a kuduro show that went from the afternoon well into the night. And it was very interesting to see how he moderated the show to the masses who were in the stadium, and then he went backstage and picked the next person to come on stage! The ranks were filled with kuduristas waiting to come on and he picked them rather spontaneously. He just said, you come on now, you come on now, you come on now. And it was interesting to see that even at such a large-scale event, things happened pretty much on the fly. And he’s very, very good at that. At maintaining, pulling, holding the whole event together. As a master of ceremonies, he dominates the stage.

NS: What do these acts consist of? Solo rappers? Dance troupes?

SA: It could be any kind of . . . usually, there’s at least one vocalist. It could be one vocalist, in the case of, for instance, Noite e Dia, who was the glamorous star of the night. She didn’t have to wait, she came rushing in, parachuted in and then rushed out to the next gig. She just came by herself, danced and sang.

NS So when someone gets called up to the stage, how do they get the track they want on the system?

SA: Usually the performers, vocalists, give, or even the dancers give a CD-R that has one or more tracks on it to the DJ, as in the person who presses “play,” not necessarily the person who produced the track, and then says, “play track 8.” It’s quite common to have a little bit of confusion at the beginning [laughs] of a kuduro show – “No, not that track 8! The next track! No, before!” That’s usually how it works. I’ve seen this a lot at kuduro shows and competitions: the performers hand their CD to the DJ as they are entering the stage, and then when they have the mike, say “play track 8,” “play track 2.”

NS: When did Sempre a Subir start? . . .

SA: I first noticed it through online recordings that people put up on YouTube, I think, in early 2010. And when I asked Coréon Dú about the show and when it started, he couldn’t quite recall whether it was 2009 or 2010, so I think somewhere towards the end of 2009, beginning of 2010. It’s a weekly kuduro show that on

national television, TPA 2, so, basically, the pop channel of national television. When I first saw it, it was broadcast every Saturday night, that was last year, around six or seven o’clock in the evening, but I think it’s repeated several times too during the week. It’s produced on Wednesday, and kuduristas, dancers, vocalists – usually vocalists – wait in front of the national radio building and they hope to be selected. I don’t know exactly how the selection process works, because I also know that DJ’s, producers, managers, like DJ Devictor, try to bring people that they work with – singers – into the show. Other people go by themselves. The basic format is, it’s an interview show where two people who may not know each other are set on two stools, and the anchorperson in the middle, and they try and start verbal dueling between the two. They interview them first – where do you come from? What’s your neighborhood? What’s your style? Do you think you’re the greatest? Why do you think you’re the greatest? And then they try and instigate some kind of beef between them. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t. And then they play kuduro videos between. And sometimes there are also interviews with – it varies a little bit, but the basic format is, interviews with two people that are then supposed to start beefing each other.

It was not only Sebém, it was Karina Gonçalves, his female sidekick, so it wasn’t him alone. Apparently he went to jail for not obeying the police in some kind of car-related traffic conflict. People tell different stories. Some people say he said rude words, some people say, well, he didn’t pay a fine, he missed some deadlines and then apparently was rude to a policeman and so he had to go to jail for it.

He put together a kuduro group in jail! We were supposed to visit him, but it wasn’t possible because he was busy performing in other jails with the new troupe he’d put together! He’s out since the beginning of August. I’ve seen on Facebook photographs where he’s appeared with video producers and then on other websites . . . so I’ve seen pictures of him but I haven’t seen any official public appearances.

I’m wrong. I’m sorry, I forgot. I saw a photograph on Coréon Dú’s Facebook page, with Coréon Dú in the middle, Tony Amado on one side, and Sebém on the other.

The show went off air for, I don’t know how long, a short period. And then the duo Os Namayer, or better known as Presidente Gasolina and Príncipe Ouro Negro took over the role of anchorman for this show. They are two very flamboyant kuduristas [laughs].

NS: How did the show change?

SA: It’s hard to compare. They sing and they dance. Sebém doesn’t dance so much. He’s very vibrant and physical in his appearance, but he doesn’t dance as such. They do dance. They’re a different generation. He’s regarded as one of the first generation. They’re seen as the second or third generation. They’re very tight as a

unit when you see them on stage. They interact blindly. They have their own language. . . literally, they created their own slang, a portuguesaire, they stretch some vowels and put different intonations on the Portuguese that they’re using, so you have to grow accustomed to it to understand them. It’s one of the trademark features, is their own language that they created.

Sebém has a different scope of experience, having lived abroad and being part of the creation of the genre. He has a different standing in the scene and he has a different – he dominates the stage differently, which is not to say that those two don’t dominate the stage. You see more history when you see Sebém on stage, that’s maybe it. But I think it’s also very interesting to have this new generation bring fresh blood.

NS: Is all of Luanda into electronic music now?

SA: Pretty much. I can’t give you percentages, but if we keep in mind that there was a civil war, during the 1980s acoustic instruments became very hard to come by, so people started musicking with keyboards and playing CDs and DJ-ing. Even what we call “classical music” is completely media-fied worldwide, because it’s recorded digitally, it’s manipulated, so I would say it’s pretty much electronified. Besides kuduro, we’ve got a huge influx of South African house, we’ve got tarraxinha, which is the slow-grind R&B of Angolan music – it means “little screw” –

NS: It means what?

SA: Little screw! Some people say it’s sex with clothes on. DJ Znobia makes fantastic tarrachinha.

NS: What’s the kizomba scene like?

SA: It’s hard for me to say what the kizomba scene is, because from what I’ve seen in Angolan musicking or dancing, be it at the club, be it at the street corner, be it at the schoolyard, or be it at the semi-private backyard party, they’re usually mixed parties. There are musical genres from rebita, semba, tarrachina, kizomba, kuduro, Afro-house being played, and mixed also with international genres, so it’s hard for me to say if there even is a kizomba scene. It’s interesting that there is a documentary called Mãe Ju, about a famous discotheque called Mãe Ju, where kizomba, tarrachinha, and kuduro were played and danced a lot. And Gata Aggressiva says that “who doesn’t know to dance kizomba, I don’t regard as an Angolan.” I can’t tell you if there’s a scene as such, but I would as a sweeping generalization say that every Angolan knows [how] to dance kizomba.

NS: What’s a backyard party like these days?

SA: The DJ might start with slow jams, with old acoustic music from the 60s and 70s, maybe mixing in some Cuban music, Congolese music, and then slowly step up the pace as the night proceeds, then culminate in kuduro, house, and then slowly take down the energy again.

NS: How big is Afro-House?

SA: It’s big. Afro-House is big in Luanda. There was a debate last year whether Afro-House is killing kuduro, or who’s unfaithful by stopping to produce or dance or sing kuduro and starting to produce or dance or sing Afro-House. I think that was also the motivation for Sebém’s event, for the “Kuduro Não Para” – Kuduro doesn’t stop. The big popularity of Afro-House, which, surprisingly, some people call Rouse.

NS: Huh?

SA: Some people call it house, some people call it Afro-house, they call it Afro-beats, but some people call it Rouse, Rouse as if it’s a Portuguese word from Brazil, as if Brazilians pronounce it wrongly and there’s a hypercorrectivity of turning what sounds like a Brazilian “r” into a[n Angolan] “r,” but it was never an “r” to begin with. It could also be just “Afro-house” pulled together into “rouse.” I think it’s both – it’s a hypercorrectivity and also just a contraction of “Afro-house.”

NS: How is Angolan house music different from Chicago house music?

SA: Sorry, I have to be academic about it. I can only answer what I’ve seen, but I would say that Afro-house that I’ve heard and witnessed being produced and DJ-ed, as compared to Chicago house, I think one of the differences is that Afro-house is purely produced with computers, MIDI controllers, and nothing else, so it’s a lot more quantized, and you wouldn’t hear tape edits, or you wouldn’t hear the beauty of machinery, being able to figure out, oh this is this synthesizer, or this is this drum machine, or it’s this keyboard that’s being used. So it’s a lot more – I wouldn’t say standardized, because people are very, very creative about making Afro-house, because it’s very quantized. At the same time, it has the very interesting, sexy shuffle beat about it that reminds me of kizomba, reminds me of tarrachinha – it reminds me more of kizomba and tarrachinha than it reminds me of kuduro.

NS What about the rivalry between neighborhoods as expressed in kuduro?

SA: When we organized the conference, we incorporated this question, the question about, does kuduro come from the musseques, does it come from the periphery, does it come from the self-organized neighborhoods, does it come from the city? We had a whole panel dedicated to this question, and the gist of it is, there’s a dynamic between the city center and the musseques. The informal neighborhoods don’t necessarily have to be in the periphery, but the big ones are. There’s Sambizanga, there’s Rangel, there’s Cazenga, they’re all big, self-organized, informal neighborhoods of one- or two-story buildings with unpaved streets. At the same time, in kuduro’s history, we have these discotheques, these downtown discotheques, and we have means of production in the hands of people who live in the city, and we also have means of production and knowledge with people who travel from Luanda to the diaspora and return with knowledge, with media, with records, with CDs, and what-not, so to me it’s a big dynamic, this whole creation process. Some of the key producers live in the center of town. A lot of studios in the musseques. I think this whole debate about kuduro being from the musseques, being from the center of town, is an indicator for certain classist attitudes toward kuduro that are saying, it’s not really music, it’s just noise, it’s animation, people don’t know how to make music, the beats are constantly distorted, people are forgetting their traditions, it’s just about showing off, anyone can shout like that – so I think this whole debate, rather than being about clarifying certain lacunae in the history of kuduro, is more about positioning yourself as somewhere in the Angolan class system, which is really very fluid, but for the people who make kuduro in the informal neighborhoods, it’s central to their identity to say that it comes from the musseques. For instance, DJ Killamu’s studio is called Gueto Produções, it’s in Rangel.

NS: What about the association of kuduro with gangs?

SA: Speaking to people, I wasn’t aware of that. I thought it was more of a classist attitude that reflects in certain debates. But speaking to people more and more, I found out there were actually, what do they call it, groups, or turmas – especially after the civil war, so after peace from 2002, you imagine Luanda is on the brink of becoming a mega-city, lots of people from different areas in the country move to the informal neighborhoods, and everyone’s just struggling to get by, people are being relocated, and what not. In this climate, apparently, there were youth gangs. And some people told me that at a certain time, the majority of young men were gang-affiliated in certain neighborhoods. And apparently this has changed a lot, also, because people were doing kuduro, and some bands, such as Os Lambas from Sambizanga, are cultivating a gang image. And there were two movies – I can send you the correct titles, A Guerra do Kuduro, or something like that, where Os Lambas participated, and it was pretty much a blaxploitation set in Luanda, and that was what caused, on national TV, I think, and that stuck in the images of people. But we do have a strong affiliation of popular music with sports clubs and any kind of informal or more or less formal organization of groups of young men since the 1960s, since the Portuguese allowed Luanda to thrive a little bit as a modern city from 1961, we have these different affiliations of young men in sports clubs, and they would also make music, and also get involved in politics at the same time, and I think this kind of carried through to kuduro.

A formal music industry as such, with distribution networks that we’re used to in North America and Europe, is only just about to bud. So a lot of kuduro is organized informally, and people organize themselves in “staffs,” they call it staff, such as people who work somewhere – a group is a staff, they use the English word staff. We have staff do milindro, which is a dance crew, and people just say, we have a staff, or production companies. People like to roll in groups.

Also, this is how you make a career, you hang about. Titica, who’s one of the most glamorous kuduro stars today, always tells the story how she was pestering Propria Lixa to be able to hang with her, and then Propria Lixa being a very established kuduro vocalist at the time already, so Titica made the big effort to be able to roll with Propria Lixa and crew, and then later to be able to dance with her as she developed into kuduro’s most glamorous star today. So this whole informal music industry also allows for structures to emerge more organically. It means people roll in groups, they hang out together. I think for the uninformed observer, this might also be looking something like a gang, and I think it’s also – when I went to Luanda, my friends would introduce me to their friends, and say, yeah, she’s here to research about kuduro, and then people would say, ooh, but that means you have to enter . . . the informal neighborhoods! And I’m like, yeah, what’s the problem, a lot of people live there. I think there’s a certain way of – a small portion of the population of the Luanda to avoid the informal neighborhoods, the musseques – and a way of seeing them as places of crime and whatnot, and then at the same time, people actually go there all the time, or they live there.

SA: Yes and no, because we also have – I can’t say. Also, there are certain standard complaints from the side of the kuduristas, like – the government doesn’t support them enough, the ministry of culture doesn’t care, people see them as gang affiliated and they don’t see the hard work, kuduristas are being treated badly as compared to other artists, kuduristas get a crappy backstage where the kizomba artists are getting fancy backstage areas and whatnot. So I think there is a music industry that is recording kizomba and semba and other style, and that’s . . .

I think it pays off, first and foremost, as distinction. You gain not so much money to begin with, you gain distinction. Which is a big part. So how do you make money doing kuduro? Or maybe I should rephrase the question more broadly: what do you gain? What’s the payoff? I think the payoff is manyfold: it’s not first and foremost monetary. They payoff is, you get to hang with cool people, you get distinction, you get something meaningful to do. We need to know that school starts quite often at five in the afternoon, and imagine you’re a young person hanging about the neighborhood.

NS: School starts at 5 in the afternoon?

SA: For some people, yes. For many people. People have a lot of spare time during the day, which for me is also one of the explanations for why people can sharpen their skills – their dance skills and their rapping skills – and produce kuduro. There’s a lot of spare time. A huge part of the population of Angola is under thirty, and they all live – not all, but many of them live crammed together. So you have spare time, and lots of young people, crammed together in places. So it’s good that you have music. [laughs]

NS: So what’s the payoff?

SA: The payoff is, you can get famous – you can get famous quickly or for longer, and also there’s a big investment, because it’s interesting for us, that kuduro singers pay for a lot of the things that we would think that you’re actually making money. So, for instance, in order to go record your song, you pay a certain fee. You pay to be able to use a track, an instrumental. If it’s exclusive, it’s more expensive. And if someone else has used the track before, if it’s being recycled, it’s less expensive. So depending on how much money you have, you might end up with a recycled instrumental, pretty much as we know it from Jamaican dancehall. You then go from the studio where you just recorded your song to these people who put the compilations together that are being sold on the street in the form of mp3s, and you pay them to include your song into a CD compilation that may be played on the streets. Then also apparently there’s payola to get your music played on air. Some people confirm, others say it doesn’t happen, but a lot of people say there’s payola to get your music played. So first and foremost, it seems that you need to make a lot of investment.

NS: So when Titica plays at the Cine Trópico with $100 for the balcony and $250 for the VIP, who makes the money?

SA: Well, she came on stage with, what? Ten dancers, and a seven-piece band that night.

NS: Tell me about the show [Titica, July 25]. . .

SA: It was very well put together. The setting was interesting, because it’s more like a theater, with tables where you could serve yourself food at the buffet, which had lobster, but also beans and cakes. Very glamorous crowd, very established crowd, people recording the show with their iPads. Titica had invited a lot of artists – very established artists, such as Ary, or C4 Pedro, and also Noite Dia, one of her kuduro colleagues, also came on stage. She had prepared a fabulous live show, with five female dancers, five male dancers, a live band with three backing vocalists, and what? – seven musicians, can you recall?

NS: Six, I think . . .

SA: It was very well choreographed, the whole thing, and we both attended the rehearsal, so you know they rehearsed. It started off with the big LED visual in the back that was a big fire that was burning in the back of the stage, and even before the band came on, other acts came on, like . . . a funk carioca singer. If you think kuduro is raunchy, I don’t know what this was.

NS: Explicit?

SA: Very explicit lyrics.

NS: Like, Brazilian baile funk?

SA: I prefer to call it funk carioca, because that’s what the people call it. Daniel Haaksman released a Baile Funk CD, which I love, and I love him, but I think the name of the genre is funk carioca. Yes, this is the Brazilian funk from the favelas of Rio. Oh, and lots of artists came on, and she incorporated . . . there was also a house singer. There was a warmup part and then there was the Titica show proper, and she constantly brought friends on, and she said to me in an interview before that she is a great fan of Fally Ipupa, singer from Congo, and she also went on stage to dance with him in the previous concert, and she incorporates more and more Congolese dance moves and guitar styles into her live shows, so she had translated all of her songs, or the musicians had translated all of her songs that were produced electronically by DJs like DJ DeVictor, into a live-band arrangement with three backing singers, background vocalists. It was great.

NS: How would you explain Titica to the folks at home?

SA: Titica is officially twenty-five years old, a kuduro star. She has come a long way. She was born as a boy, and started with traditional dancing, then as I said before, was pestering Propria Lixa to be a – she wanted to hang with her, roll with her, and dance with her. She also started singing quite early, when she was still a boy, and that didn’t work out for her, so she focused on the dancing, then became a dancer of Propria Lixa. The same promotor, Riquinho, who put on Titica’s show now, two months ago – he also invited Propria Lixa, and Titica went with Propria Lixa to dance on stage, and Riquinho said, well, Propria Lixa, from now on you have to bring the little gay boy with you or I’m not going to book you any more. So she slowly worked her way up as a kuduro dancer, dancing with Noite e Dia, Propria Lixa, Puto Lilas I think also. But she really wanted to sing, so at some point Tuga Aggressiva – also an established kuduro singer – invited her to contribute to her track, “Afrike Moto,” which was released in 2010 or 2011, and Titica sang with Tuga Aggressiva on “Afrike Moto,” and apparently everyone loved it.

And from then on she went solo as a singer, and she had made the transition from dancer to singer, which is something that quite a few kuduro dancers aspire to. She is with LS Produções, a production / management marketing company that’s very well established in Luanda, and she released her album Chão – Floor – last year, which is a proper album, it’s nicely produced. She’s very glamorous. About four years ago she got breast implants in Rio, and is the most glamorous performer you could ever imagine, if you look at her in her six-inch heels and her hair and her lipstick and her outfits.

NS: . . . How does Buraka Som Sistema fit into all this?

SA: Well, what’s interesting is, if you look at the video Sound of Kuduro, where they drive along the Marginal, the Bay of Luanda, they say in Portuguese: “we’re here for the first time. We’ve made it.” And one of the band members, Kalaf, is Angolan, as far as I know. How do they fit into this? I think they’re very much inspired by kuduro. They took it to an international audience, and I think they paved the way for other kuduro projects to get more international recognition, and I do like their music from the time. And also, in this video, Sound of Kuduro, they incorporated images of the musseques, and of DJ Znobia’s studio, and . . . of established kuduro singers in Luanda, and I think it’s a good way that they’re connecting this, that they’re harking back to the Luandan scene and reaching out to these people, and at the same time, I think they were trying at the time to get a bit more credibility by doing that, but there’s nothing wrong with that. [laughs]

NS: Does kuduro work in an audio-only medium, or do you need video too?

SA: You’re asking the wrong question, Ned, because kuduro resides on the dance floor. Video may seem a more adequate medium to capture dance moves, but really it only comes to life when you see rocking out to kuduro. It may be three-year-old girls dancing on the street-corner, or Titica on stage, or a 60-year-old mother in a backyard party, or a well-rehearsed kuduro dance performance in the schoolyard, so the videos also range in quality. It could be cell phone footage, it could be glossily produced videos such as Titica’s “Olha O Boneco,” and yeah, I think they’re first and foremost trying to capture some kind of performative energy that comes alive through the dance.

NS: Tell me about Hochi Fu.

SA: Hochi Fu is one of the most important video producers in Luanda right now. He runs his video production company, Powerhouse, out of a backyard studio in Praia do Bispo, which is fairly central in Luanda. He’s got two bulldogs protecting the place. He’s Angolan. He left the country for some time to live and study in Holland. He’s trained in, I think, in graphic design. And he started applying those skills to kuduro culture. He said that kuduro became more important to him when he lived abroad, and he wanted to contribute something to it. And he’s the one responsible for Cabo Snoop’s video “Windeck,” and he’s also the one responsible, according to his rendition of the story, including skinny jeans and bright colors and changing kuduro’s style dress code a little bit, adapting a little bit more with the global hipster outfits. He runs a video production company and he used to work with IVM beats, who unfortunately died in a car accident, and who produced the beats for Cabo Snoop and other acts. He’s raised the level for video production in kuduro. There are video like “Windeck,” or also acts like the Power Boys, like the “Tchuna Baby” video, that’s one of his recent releases. We have a couple of video production companies that are using . . .

NS: Tell me about the “Windeck” phenomenon . . .

SA: “Windeck” is inspired by Fat Joe’s “Lean Back.” The story is funny. It’s Cabo Snoop’s African superhit. IVM Beats made the beats, and he, walking from his house to the studio, would always see the boys who were guarding and washing the cars, and they would sing – apparently they were on drugs, I suppose some people suck on gasoline . . .

NS: Suck on gasoline?

SA: They would take their T-shirt and dip a part of it into gas, into petroleum, and then suck it out of the cloth. That’s what the street kids do. That’s what the kids did when we went – didn’t you come and see me at the record release? At the square?

NS: For Madruga Yoyo?

SA: Yes.

NS: I remember kids in Brazil – this is twenty years ago already – sniffing glue in the street . . .

SA: Yeah, well, I think Brazil’s been crackified, pretty much. And fortunately, Luanda hasn’t. So the car washer’s warbled rendition of Fat Joe’s “Lean Back” came out as “Windeck,” and IVM / Cabo Snoop picked that up in the production process. And it’s everything that’s baaaaaad. Windeck is trying to get money out of people. Windeck is trying to take advantage of tipsy girls. All of that is Windeck.

NS: Tell me about y’all’s kuduro conference in May.

SA: We organized a kuduro conference that was three days long in Luanda in a very beautiful old cine-teatro, Nacional Cine Teatro, which is also the place where the cultural association Chá de Caxinde sits. It was under construction at the time and we had little bits of things falling out from the ceiling, because the ceiling was full of woodworms, but that couldn’t stop us. We had three days that were packed with panels, films . . . we had a glamorous opening ceremony with Tony Amado, with Presidente Gasolina and Príncipe Ouro Negro. The Vice Minister of Culture spoke as well. Coréon Dú spoke. And we managed to bring together international researchers who work one way or the other about kuduro. We had guests from England – an Indian British researcher we had – we had a Cuban researcher, we had Benjamin Labrave, who runs a record label out of Accra, in Ghana – Akwaaba Records. We had Garth Sheridan from Australia, Marta Lança from Portugal. I’m forgetting people, I’m sorry, but this very illustrious round. And we had lots and lots of Angolan people. Coréon Dú was presenting, Jomo Fortunato, Jó Kindanje, the author of the first book about kuduro. And we had a beautiful audience of Angolan academics, Angolan media people, and we had lots and lots of kuduristas, which was the most beautiful thing ever – to have an academic conference with the people who actually live the culture, that was the best to me.

NS: Tell me about Elinga Teatro . . .

SA: Elinga Teatro is a cultural association, it’s like an NGO. It’s currently residing in a very beautiful old Portuguese building with big French windows and it’s got a roof terrace, you can look out on the bay. It’s the rehearsal space for the dance troupe, for a traditional dance group that I was also allowed to rehearse with. It’s also the rehearsal space for contemporary dance, it’s the rehearsal space for children’s percussion projects, it has club nights on – it used to be on Wednesday, but steady club nights on Thursday, Friday, and Saturday night, it changes its face all the time. And was also the place of the two-week theater festival, also during the conference, so there was lots going on in the city at the time. It’s a theater, club, a rehearsal space, but also a meeting ground for the creative scene of Luanda. It’s been declassified. It was listed as national heritage. Now it’s been declassified because of a big building project in front of it. A big high-rise tower is in its early stages of building, and that space will be used as . . . the parking space of a big high-rise tower. It’s a blow to the cultural scene of the city.

NS: You DJ-ed at the Elinga under your name of Stef the Cat, right? What was that like?

SA: It was cool because my dear friend Sacerdote organized an afterparty for the conference, which I’m very grateful for. Benjamin Labrave could DJ there, Garth Sheridan could DJ there under his name of Unsound Bwoy, so it was really cool that we could present at the conference and then DJs together later, it was a really sweet bonding experience. Also together with DJ Buda, a local kuduro DJ, it was great, because I only took with me a selection of mp3s, and Garth very kindly let me use his Serato system and his controller, and we were slightly detached from the crowd, because we were up on the stages above the dance floor. So it’s not so easy to keep the emphatic channel open, but I played a mixture of Chicago juke, dubstep, and kuduro, and slow hop, and weird, challenging things, mixed with old school kuduro, so I wasn’t expecting people to dance, I wanted to challenge the audience, and so I also asked to play the first slot, so I wouldn’t kill the dance floor. And it was great.

NS: How long have you been DJ-ing?

SA: I started DJ-ing in 1996, out of a love for vinyl collection – I started collecting vinyl when I was little, when I was a child. I moved to Berlin in 1994 and at the time it was still the big club explosion after the Wall had come done and there was also the big techno-club explosion, but there was also a very busy scene of living-room bars going on, because there were so many old residential buildings, and we would run living-room bars out of old flats. And there was also a big flea-market scene going on, and there was an easy listening, and jazz, and anything that wasn’t so much electronic music scene going on. And I started DJ-ing, because we ran the Poppy Bar, and we called the Poppy Bar the Poppy Bar because the wallpaper of the kitchen in the flat that we were running the bar out of was all poppies, all over, on the ceiling and on the walls, and so I started DJ-ing, and it worked, I loved it, people liked it, I got booked for things, anything from weddings to street parties to clubs, and I applied for the Red Bull Music Academy in 2000, and I could go to Dublin and spend two weeks just listening to lectures, and practicing and hanging out with DJs from all over the world, and at the end of it I had 50 DJ friends around the world, and a residency in Dublin, and I kept flying back to Dublin to DJ there at Club Velour, shoutout to Fergus Murphy, and I started doing radio there too, traveled around DJ-ing different places, France, Switzerland, Austria, then when I spent a year in Brazil I took records with me and we started putting on parties in Salvador da Bahia, and then when I came back to Berlin in 2004 I started teaching radio also as part of outreach programs of cultural institutions. I also started teaching DJ classes, mainly to girls and women, but also in general, I did that in Luanda as well. Then I noticed that if I DJ-ed three or four times a week, it’s not so good for my studies. [laughs]. So I toned that down a little bit and tried to focus more on nice, produce events like in theaters, events as part of Ladyfest, nicely, lovingly organized events, rather than playing lots and lots of events. Then I started teaching at the University of Oldenburg, I also started teaching DJ-ing at the university as a practical and historical course. So we are reading texts on early radio DJs in the USA, and the house scene, and the acid house scene while learning to DJ with vinyl and CDs and mp3s, and the idea of the DJ workshop is usually to have the final presentation at some kind of party, so last year the students could DJ at a cinema festival in the city where I was teaching.

NS: Do you have a mixtape up on Soundcloud?

SA: When it comes to DJ-ing, I’m such a dinosaur. I think the last mix I made was on a Mini-Disc. [laughs]

NS: Peak experiences?

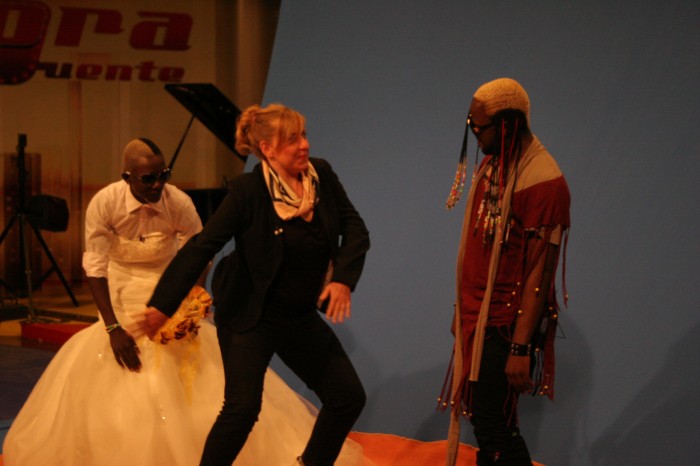

SA: You witnessed one. I think the cherry on the cake was when I was invited to appear at Sempre a Subir in the “One Minute of Fame.” It was very spontaneous, it was beautiful because Príncipe Ouro Negro was wearing a bridal dress and he had just thrown out the bouquet in the previous scene, and I could walk in with the bouquet in my hand, and then they asked me to dance and sing, which I tried to do, and then we kind of made up a little song: Mata Barata Mata Rata Mata Tudo . . .

NS: Was it completely unplanned?

SA: It wasn’t planned, but I went prepared, because Príncipe called me at seven in the morning and said, “come to the studio.” I said to him, “well, I went last week and I have so much stuff to do,” and he was like, “yeah, but come.” And I thought, this is so sweet, he calls me, and it would be really arrogant not to go. And then I went into makeup just in case, I didn’t know what was planned. And then there were these two girls who were supposed to go on One Minute of Fame.

NS: One Minute of Fame is a regular feature on Sempre a Subir?

SA: It seems like it. I’ve seen it a couple of times now, yes. It seems to be the launch pad for up and coming talent.

It’s funny, because Príncipe Ouro Negro and I have a little history like that. When I went to a kuduro party in Rocha Pinto in Luanda, which was a block party, open air, free of charge, very well organized, he appeared there. He was climbing down from the rooftops behind the stage. He was moderating, he didn’t even sing, but he had the whole audience captured. And then at a certain point, he went, [singsong voice]: “yes, and we have this foreign researcher here amongst us, and please come on stage.” And I went on stage and ripped my trousers in the process. And he interviewed me, like, what’s your name, and good evening, and I said, I ripped my trousers. And he said, “That’s kuduro!” And then he asked me to dance with him, and we danced, and everyone was very happy and I was very happy. And then we met again in Berlin when they appeared at I Love Kuduro, so we’ve had this adventure together.

NS: What’s it been like living in Luanda?

SA: It’s a very high-paced city. It’s a big city, it has unoficially about eight million inhabitants, a large part of whom live in sprawling-out neighborhoods. The public transport is 95% self-organized in minibus taxis. You have frequent power cuts, and the cost of living is very high. Luanda ranks among the most expensive cities in the world. And that makes it difficult to communicate with people, because you have to top up your phone all the time, and a lot of people don’t have credit on their phone, so it’s hard to ring people because you have to be quick on the phone, or people can’t answer because they don’t have credit, so that makes it hard. On the other hand, I must say that people have been so, so, so cooperative, and I feel so blessed with how people accepted me into their world. I wouldn’t say it makes up for the difficulties, but it – yeah, it does make up for the difficulties. I must also consider that I’m in this luxury world, I can travel back and forth, I had a generator in my back yard so when the power went off we could switch off the generator. When there wasn’t any water coming through the pipes we had a water tank, so I wasn’t affected by the difficulties that Luanda has as much as my research partners. People are very persistent as well; there are a lot of difficulties, but people keep pushing . .

NS: What role do candongueiros play in the distribution of kuduro?

SA: Candongueiros are very important in the distribution of kuduro. They are the blue and white Toyota minibus taxis, and they have certain fixed routes through town. The big nexus is Mutamba Square in the center of downtown, the Baixa de Luanda, and you have to figure out what the main routes are and you just need to check to people a lot and ask them . . . so imagine you’re going from one end of town to another, and you’re meeting someone, and you may not know the person, and you don’t know the area, and you have to figure out how to get there. So you ask the person that you’re meeting, how do you get there from Mutamba? They’ll tell you, take a taxi from Mutamba to São Paulo, and from São Paulo you take a taxi to Cuca, and then you take a taxi to Cazenga. You try and memorize this on a notepad, or in your phone, or on your hand. And you repeat it at every next stop you’re going. You jump into a taxi at Mutamba and then tell the person where you want to go, and verify that this is the best, or quickest, and safest route to go. And they might confirm or offer alternative suggestions. And that’s how you start chatting to people.

Taxis very often play loud music. They play a lot of kuduro, but they might play house, or they might play Christian sermons, or Christian music, or just the news, or rap.

NS: What’s the interior space of a candongueiro like?

SA: There are usually three or four benches in the back, and you have to squeeze in to fill them all up. You are told that one bench takes four people and if you think otherwise, you’re told. If you think it only takes three people, other people try to get on the bus and you’re told that this bench takes at least four people and you need to squeeze in. And quite often it’s the case that a mother would enter with one or two children, and you take one of the children on your lap, and you would often see – it’s usually organized so that there is a driver and a money collector. You might think the taxi’s full, but then the money collector gets in and he sticks his behind out the window so the taxi can go.

It’s a very, very interesting social space, and what I like about it, it’s based on politeness and cooperation, not only from the people who are operating it, but also the people who are traveling in it, because you have to cooperate. Otherwise it doesn’t work.

NS: How about that detour we took . . . ?

SA: [laughs] One thing that I haven’t talked about was the traffic of Luanda, and at certain hours of the day, certainly between five and seven in the evening, when the city is at an absolute deadlock. And we had a clever candongueiro driver who said, I’m not gonna stick this out, I’m gonna take a short cut through the neighborhood Prenda. And the taxi went through back lanes, the becos, that weren’t asphalted, and we had about an arm’s length of space between us and the houses, no? Between the car and the houses, and it was dark and unlit, so there wasn’t much to see apart from what the . . . there were people, and dogs, and children, people were carrying things on their heads, maybe generators or water tanks, and whatever you have in a neighborhood that is not laid out for cars driving through it. It’s a walking space, basically. And it’s also a space where the private and the public very much merge into each other. And so I think that was also why it seemed so odd that this big car was going through the space. It felt like going through someone’s garden, or living room.

I took other detours. My last day I was invited to a videoclip that was being shot, and that I was allowed to participate in, of Fogo de Deus and Manda Chuva, and it was a Sunday, so not very people were going, traveling around the city, and I was going to take a taxi from Mutamba when one of the drivers called out my name. And I was like, it can’t be, the TV program was only last week. Why is he shouting my name? And it turns out that he was also the plumber who moved our water pump, and he remembered me, he was like, Stefanie, come into my taxi! And then I was the only client in the taxi. We chatted and I was like, how are you doing, are you also a cab driver in addition to being a plumber. So we’re going up – we’re supposed to go to São Paulo – and there’s an elderly lady waiting. She’s got a headwrap, she’s wearing a pano, she’s wearing a wrap around her hips. And she’s explaining the situation like, she wants to transport a door, but she’s very timid about it. The guys are like, yeah, cool. There’s the driver and the money collector. And she’s explaining her situation, but she’s shy about asking if they can transport the door, because I’m a client in the taxi, and I’m like, seize the opportunity! Get your door transported, woman! Let’s do it! They get in the door. It’s a big metal door, it’s taking up all the space in the back seat. She’s kinda crammed in on the side. And then she’s like, “yeah, there’s also a couple of tiles that need to be transported.” And I’m like, sure, let’s do it. We go onto a different road – we’re off of the route now – and the driver and the money collector are carrying big packages of floor tiles [laughs] to the back of the taxi and it’s taking some time, and then we’re going towards where she needs to go and I’m like, yeah, we’re off the route. And Fidel the driver says, yeah, but it’s much closer to where you need to go. And he wouldn’t accept any money in the end.

Another time there was a candongueiro passing in front of my house in Chicala. Usually there aren’t any candongueiro routes, and it was on a Sunday. I got on, and they’re going like, yeah, we’re going to São Paulo, where do you need to go? And it was full of women, and everyone was drinking cans of Cuca, including the driver and the money collector. Everyone was in a cheerful mood. The driver was asking where I wanted to go, and I told him, “but you don’t need to make a detour for me.” He was like, well, sure! And the women got kinda put off, and they didn’t like the fact that he was making an exception for a foreign woman, so I was like, no, no, just go on . . . they were opening more beer cans, and it was as if the route was open to discussion. [laughs] Then I left the taxi at Kinaxixe and walked the rest of my way.

I forgot to say that the candongueiros played kuduro. Candongueiros are a key element in the chain of kuduro’s distribution, because the kuduristas take their music to the taxi drivers, ask them to play it, and then the taxis going their routes through town play kuduro and make certain songs popular. The focus of my research is kuduro dance, and I think that’s the most intriguing part of it, too. I do like the music, I do like the rapping, I do like the instrumentals.

NS: What do you see in the dance of kuduro?

SA: I see a blend of different types of dancing. I see breakdance and popping and locking and house dancing and also Michael Jackson moves. Tony Amado was a Michael Jackson impersonator before he became the creator of kuduro dance. I also see elements of traditional Angolan dancing, even though I’m not an expert, a blank that I need to fill in. It was very interesting, there’s a dance move called apaga fogo – put the fire out – by Noite Dia. You tap your right foot on the floor while it’s moving backwards and it kind of creates a vibrating sensation in the whole body. And if you dance the cheeky version you wave your hand between your legs like a fan, and if you dance the tame version you just wave your hand around in front of your chest somehow. When I went to a school party performance of a kuduro dance troupe, there was also a traditional dance group. There are traditional dance groups everywhere. They were performing a little narrative piece, and at a certain point there was a dance move that was very similar apaga fogo that we see in kuduro dance. And the schoolchildren were commenting on the traditional dancing, “oh, this is apaga fogo! Look! This dance move is apaga fogo!” So we see some of the basic elements we see in west African dancing, but also urban dance that’s circulating on the west coast of Africa. And we see also, especially in older kuduro dancing, very graphic elements: people slap themselves on the face, or they fall over, they fall from buildings, or they suck their stomachs in so they look like starved Africans from the television. They pull crazy faces, or ugly faces that they call cara feia, which means “ugly face,” or pretend to be disabled. And we also have very famous disabled kuduro dancers, like Costoleta, who has the big African hit “Xirirí.” He’s Angolan, but “Xirirí” is very popular in Ghana and other countries. So I see these three elements: North American vernacular black dancing; traditional Angolan west African dancing, and this graphic theatrical movement that seems to be references to the recent Angolan history of wars and violence.

NS: And that brings our interview to a close . . .

SA: You’ve got two hours to listen to! [laughs]