Sir Victor Uwaifo’s presence looms over his birthplace, Benin City, Nigeria. His name comes up in any conversation about music in Edo State, and many musicians claim him as an influence. Born in 1941, he made a significant impact on Nigerian popular music with a string of international hits throughout the 1960s and '70s. He still performs and records, but has increasingly focused on sculpture and writing. He served as the Commissioner for Arts and Culture in the state under Governor Lucky Igbinedion, and was recognized as an honorary member of the Order of Niger in 1983.

In December 2016, I visited Sir Victor Uwaifo’s home with Professor Austin Emielu, a musician and scholar of Nigerian music, based at Kwara State University, and our research assistant Dan Omoruan. Austin is the coproducer of our upcoming Hip Deep program "Edo Highlife: Culture, Politics and Progressive Traditionalism." “He’s really a star, that's why we call him ‘Superstar’ here, in fact, he calls himself ‘Superstar’ as well!” Austin told me. “When we talk about Edo popular music, he’s the one who actually brought Edo music to the limelight. It was Victor Uwaifo who pioneered this kind of highlife that modernized Benin music, so he brought Edo music into the mainstream of highlife. He was not the first to start it but he made it very popular.”

Our visit began with a mandatory tour of Uwaifo’s Revelation Tourist Palazzo, a combination history museum/archive of awards and posters and paraphernalia from Uwaifo’s lengthy career, and a collection of Uwaifo’s original sculptures, some of which border on the grotesque and gruesome. We were led through the museum by Uwaifo’s manager, Chris Osaredo Eburu, a knowledgeable and vociferous guide.

When we met the superstar himself in his office, he was pristinely dressed in peak late-1970s fashion with white jacket and matching hat, red shirt, huge shades and silver cross on a chain.

His desk was covered in books, newspaper clippings and other things. He immediately gave us a copy of his latest self-published book, Biomimetics of Sculpture: And What Is Art? “I am a maestro, I'm a sculptor, I’m an architect, I'm an engineer, I'm an inventor, a philosopher, I’m a sportsman, and I'm a humanist.” Uwaifo told us. He took us from his office to his lavishly furnished, spacious living room.

A life-size sculpture of the man himself stands, without a pedestal support, in the center of the floor, an example of Uwaifo’s biomimetic sculpture style. We sat down on a pair of throne-sized chairs on a raised dais under a chief’s umbrella, and Sir Uwaifo told us some of his story.

Sir Victor Uwaifo: As early as 12 years old, way back in Benin here, I started playing guitar, based on Latin-American Spanish type of music. I grew up in an era where the gramophone was the in thing. Gramophone is a kind of device that you just wind and you release it and it starts playing. I still have one there that I will demonstrate; if you had a gramophone, you are a big man. You had a gas light to go with it, oh, you are extra big! So if the gramophone was playing in my house, my father had many types of records but especially when he played the GV records, those were the ones that appealed to me because they were mostly guitar.

I constructed my own guitar using plywood and using bicycle spokes for the frets, and traps for the strings, and a sardine opener for the tuning pegs. I was doing pretty well, and after a year I went downtown by a palm wine bar, and I wanted to play their guitar. It was difficult because I tuned to my own taste, it was like the Hawaiian style, do, re, mi, do, sol, mi, do, whereas theirs was the Spanish style, which is EBGDAE. So, they promised they would teach me their own style if I bought them a glass of palm wine, and I did. So from then I started experiencing new styles. And then I later on I bought a book, some rudiments of guitar.

I attended three schools: Western Boys' High School in Benin, St. Gregory’s in Lagos—We had a music teacher, I did theory of music, and I also led the school band there—and then I went to Yaba College of Technology, I studied orchestration and management. But before then I was already playing folk songs on my guitar, and as I progressed along, I started playing with some bands and especially with E.C. Arinze. I had some recordings from 1960 and '64, and we used a band, but we called them the Pickups, we had to pick them up from different places, so I gave them the name Pickups. And then in 1964, I formed a band with some great names, some are late now, one is still living, Fred Coker, Stephen [Osita] Osadebe, and myself. We called ourselves the Central Moderneers, we did record some singles and so on.

“I graduated from Yaba college in 1963 and I worked for NTA—then it was NTS Nigerian Television Service, now it’s the Nigerian Television Authority. I worked for two years before I made a hit, “Joromi,” and I decided to resign my appointment and go full-time.

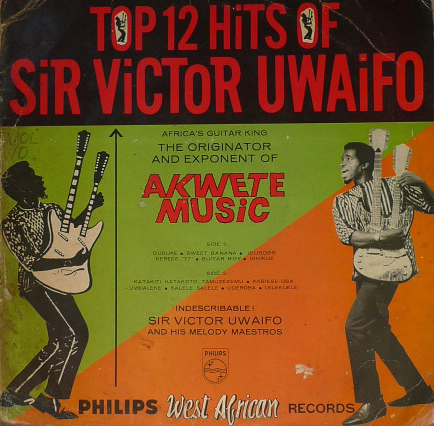

"Joromi" changed the whole game entirely. It was something different! It was based on almost like a folk but modern guitar style, and I introduced so many things, like playing with tremolo, I constructed a volume control on the pedal that when I played a note and I pulled it forward and backward it gives me a special sound. I was creating so many effects, and that really surprised listeners: I played double strings, and I go up and solo. ["Joromi"] was kind of a highlife tempo, and then few songs followed. Six/8 [time], that couldn’t have been highlife, so I called it "Akwete.”

At this point, Uwaifo became excited and asked his manager, Chris, to bring an acoustic guitar. The guitar never left his lap for the rest of the interview, and he occasionally launched into full song, for example, his rendition of J.S. Bach’s “Jesu Joy of Man’s Desiring,” as heard on our Nigerian Hip Deep Preview program.

The hit song “Joromi,” released on Phonogram in 1966, sold 100,000 copies by 1969, earning Uwaifo the first gold disc on the African continent. The lyrics, in the Bini language, were based on the legend of Joromi, a wrestler who took on the seven-headed spirit of the underworld…and was defeated. But, according to Austin Emielu, it was another song from the same period, “Guitar Boy,” that really launched Uwaifo internationally. Uwaifo picked up the story:

It was in 1966, in Lagos, at the Bar Beach. I used to frequent there after I left work at the NTA, or the NTS is it then was. One night, I was just strumming my guitar, looking for inspiration, I lay down on my camp bed. Some worshipers would come there, spiritually would come there, pacing up and down, and before midnight they would've gone, vanished. But that night, I experienced the tide was coming in easy, it would wash down, and I had to move my camp bed back, so I would not get drowned in the wave of the water. Anytime it washed down, it would leave some pearls, some cowries, and some monies and all kinds of gifts on the beach. But then suddenly I saw from a distance, a figure coming towards me, floating. Suddenly it was getting clearer and clearer and before I knew it was right in front of me and I stopped playing. My heart jumped into my stomach, I almost took off! And she cried out “Guitar boy!”

It was my scream that said “bweh” that that I transposed into the guitar that you hear. Before then nobody was playing guitar like that, so I introduced that into the song. I now transformed it. "If you see Mami Wata," she said "Never you run away." I thought it was a joke, and then she called my name, "Never you run away, Victor Uwaifo." I was down, and then she glided away, floated away. I just took my guitar, my camp bed, and I went to my Citroen car, it could almost fly! So the following day I gathered my band and I rehearsed the song.

Austin later explained, “The Mami Wata thing, it is something that's common in Africa here, water spirit. Half human, half spirit, half fish. So she could bless people. That's why he’s saying, ‘Guitar boy, if you see Mami Wata, never you run away.’”

I made my name abroad, in Lagos, and at the peak of my career, I came down to Benin. And people thought I was crazy, but I thought, “Yeah, let me come down to Benin.” I just thought that Lagos was already saturated, and Benin was a virgin land. And I need to develop my people! I built a hotel, it was called Joromi Hotel. It’s still there, but not a hotel anymore. I was running a nightclub there, and every week it was filled up, jam-packed. And that was the only thing that was happening in Benin at the time, the nightlife was at its peak, especially when I came up with the "Ekassa No.1”

So from there, I moved on to different sounds. There were Benin folk songs, based on mythologies, some historical background. I went from "Akwete" to "Mutaba." "Mutaba" I wrote to challenge soul music, because soul music almost took my fans away. Nigerians are gullible, when the soul came it swept everybody off their feet. I said well, if it is so, then I have the equivalent and I created "Mutaba," then from "Mutaba" to "Shadow." "Shadow" was a kind of dance that I fashioned after a shadow cast after an object, as you move, the shadow moves with you; if you spread an umbrella, it spreads. So I fashioned a tempo along with a shadow.

“I used to go on tours, the whole month, and I was the first to advertise on the daily Times newspaper in those days, I was just in the activities, and people would've seen it from one place to another from Kwara state to Kaduna to Jos, so they were expecting me. I didn't have to advertise every day, but each day I would just say...If I'm playing Ibadan today, I just have to say I'm playing Ilorin tomorrow. So by the time I play at Ilorin, I would say tomorrow I'll be at Onitsha, and so on and so on.

And I had a manager, people never thought a musician would have a manager. I introduced management into this business, and I also had a road manager, which is different from the manager. I do not negotiate engagement fee with anybody, it's through my manager. We would go on tour, by the time we finished, that promoted my music, too, because they would have heard my music and they would want to buy. And the songs were just coming, sometimes on the way we would just rehearse a new song, and then we would try them on the stage. The roads were not that good anyways, but the distance between the towns were so wide, that unless you moved almost immediately after finishing, you would not be able to make it. So we were traveling almost every time. And then Nigeria also commissioned me on tour, there was one we did on the Eastern block that took us almost two months. From Bulgaria to Romania to Yugoslavia, East and West Berlin, Hungary, Ukraine, Moscow, came back to Rome, that is Italy, and then Germany and then Hong Kong, and so we were just touring. Before that I had a show, the first show was Algeria 1969, and when I came back, the news came around and people read national news that some people fainted during my performance, when I was doing my breathtaking shows, when I would jump in somersaults.

“But the "Ekassa"! In 1970 came the "Ekassa" series. It also is the kind of song and dance you do when a new Oba [king] is coronated, just like this new Oba, Oba Ewuare II. Ekassa music was performed, it has always been performed during the coronation of a new Oba. I brought it to limelight, I gave it a new kind of rendition that made it danceable with a tempo almost like rock.

I named the series "Ekassa" 1,2,3, which I got from the GV series. GV records were named 1,2,3, up to GV 10. If you can still lay your hands on GV 10 today, that's the song, “Manisero.” So my "Ekassa" series were numbered, I got that affectation from that GV. And later I moved on to "Titibiti", and "Titibiti" gave me a wider scope. I could now fly: Titibiti is a bird here in Benin, it's like an eagle, so I fly like the titibiti. So that is been the trajectory of repertoires and genres of sounds.

People probably think I just play guitar and probably flute, no, I play all musical instruments. I just run away from trumpet because I don’t want to mark on my lips [Laughs]. I play the saxophone, alto, tenor, baritone sax, soprano, I play xylophone I played keyboard piano and percussions guitar and flute.”

It is commonly reported that Sir Victor Uwaifo learned guitar from Dizzy Aquaye, from E.T. Mensah’s Tempos Band, but when I asked if there was any Ghanaian influence in his music, he vehemently denied it:

No, no, no, there's no Ghanaian influence in my music at all. But I listened to E.T. Mensah when I was young, because he was much older and used to come to Benin. In fact artists in Ghana looked up to me, instead of looking up to them. The only guy that I thought was also a good guitarist, was somebody Taylor. Ebo Taylor. I don't know if he plays palm wine, but his solos were quite jazzy in those days. Otherwise, I came up with a different style that was unique to me. If I hold an electric guitar now, and there's a band it's a different thing entirely, because I have a rhythmic guitar, a keyboard and bass guitar. To listen to my "Ekassa" series, you will now hear a lot of gimmicks in my style. I play a wide range of guitar, and my style is quite different.

Even in those days in the band that I played, musicians, especially guitarist, you're supposed to be at the background, but I came with the solo and I decided to lead the band with the guitar. You'd either be a trumpeter, or a saxophonist, you had to be a horn man, to be able to lead the band. But I just thought these people cannot actually play a polyphonic instrument, so why should they lead? Do they know the kind of chordal sound of music? Progressions, modulations, syncopation? Because the nearest to guitar is the piano, but piano has about 172 strings, but the guitar has six strings and can do the same thing! That's phenomenal! So the guitar has its own place, and it's portable. I was happy that I play the guitar and I'm still playing it.

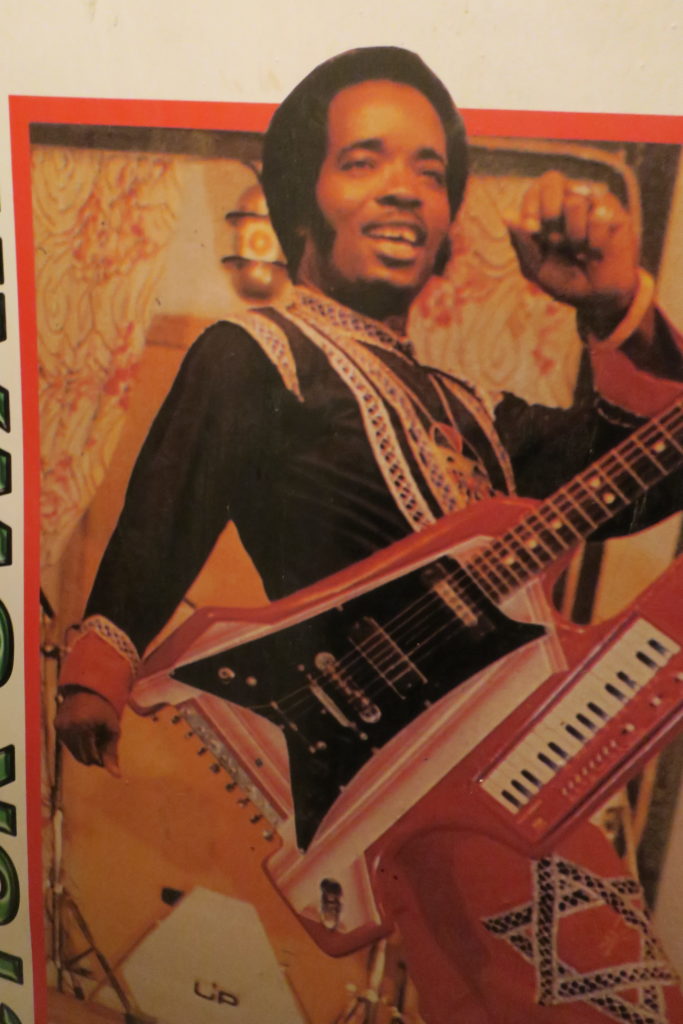

Uwaifo has also invented and built some unique instruments, including a double-necked guitar, although the first multinecked guitar was invented in 1850.

I did a double-necked guitar in those days, and simultaneously I heard that someone invented a double-necked guitar somewhere else in the world. Mine had a 12 and a six string, but one neck was short like a mandolin because I wanted eight octaves, because the piano has that, but the guitar just has not even up to five. So I shortened one neck to give me that. If you listen to “Sweet Banana,” the solo there was taken with that.

Uwaifo showed us another of his inventions: a guitar strap that allowed him to spin his guitar 360 degrees during a performance.

Austin and I traveled across Edo State for two weeks doing research into the vibrant live-band local highlife scene in the region. Edo highlife musicians often claim Uwaifo as an influence, although his music was more geared towards an elite clientele than rougher highlife music of the local bands that developed for community events.

We asked: “You were hearing Cuban music and calypso from the gramophone, but were there also local groups or traditional music that you were hearing locally? Other bands, or traditional music for burials?”

No, those people were just local. No, they were very different, different completely. In fact it was just like day and night. The type of music that I was attuned to, that my ears were attuned to was just like the day, the light. The other ones, I didn't want to hear them, because they were just like the night, dark, they didn't have form, they were just vamping and playing. There were some local musicians, but not the guitar.

So you are the one who pioneered the guitar here Benin City?

Yes, yes, yes, there were some guitarists before me but you can't actually place them, you can't figure out what they're doing, or who they were, or what they were trying to achieve. But when I came on, in fact it speaks for itself, there is no way I can describe it…Otherwise it will look as if I’m…

[He stood up and approached the statue of his own likeness] I see music, and I hear art. Like this piece of art that is here now, this sculpture I’m working on is not just a sculpture, I'm working on biomimetics. If you see the teeth, you will say that they're very lifelike. And normally people do a base for it so can stand, but I found a way for it: A standing figure is bisymmetrical with an overall vertical axis and if the weight is distributed evenly it can create an equilibrium, so this work stands on its own. The same thing with music, if you create music and it has a good arrangement, it will sound pleasant to the ears.

To hear portions of our interview with Sir Victor Uwaifo, tune in to our upcoming Hip Deep program Edo Highlife: Culture, Politics and Progressive Traditionalism. All photos by Morgan Greenstreet, except when noted

[envira-gallery id="35417"]