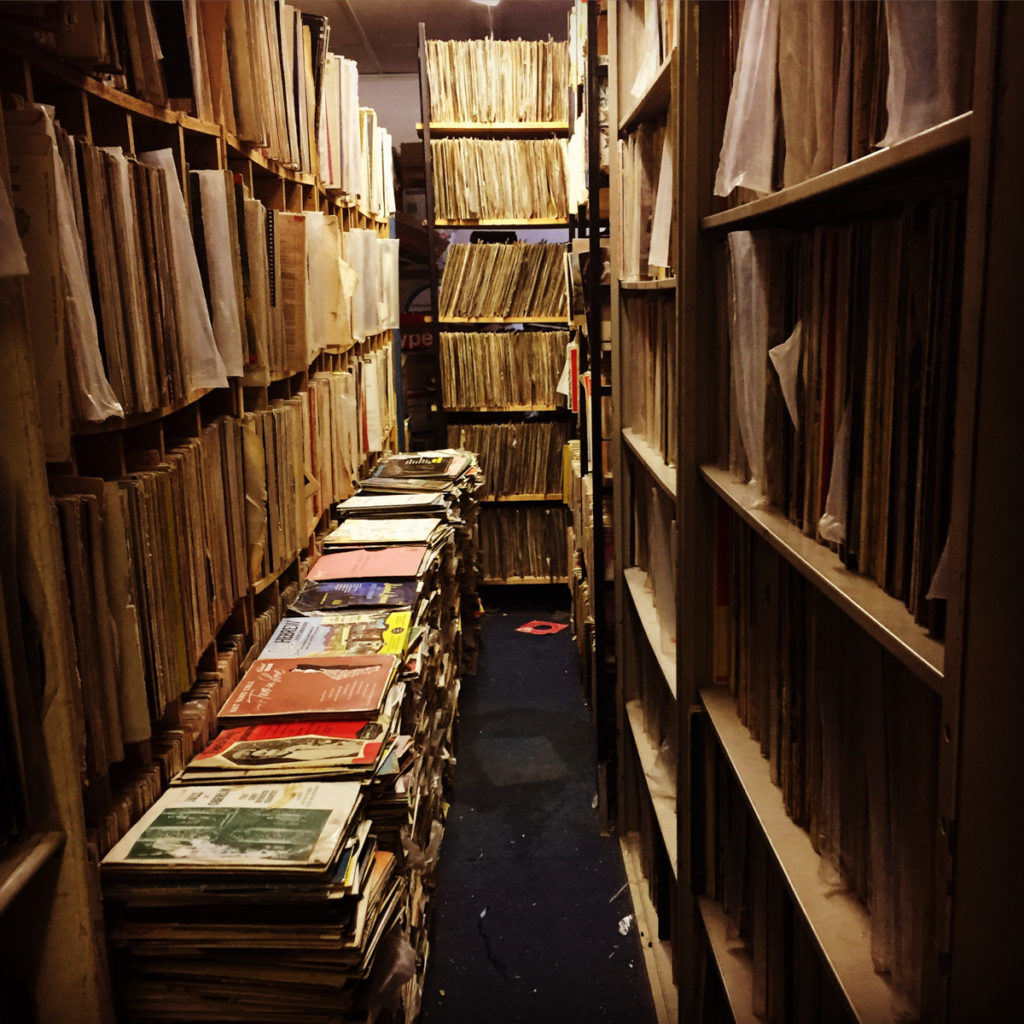

Within 24 hours of landing in Johannesburg, South Africa, I was deep into the largest record collection I have ever witnessed. Collectors Treasury is an eight-story warehouse located on the fringe of the overpass that marks the gates to the happening hot spot, Maboneng, housing half a million records and even more in books. Wait, let’s savor that . . . 500,000 wax artifacts. That is something like 10,000 days of straight listening, or about 30 years of steady needle drops. Basically, access to more music than I could comprehend. Even as my fingers did the dusty dance, it was all incomprehensible. All we crate-diggers know the idea of never-ending possibilities is more satiating that anything else. Exhausted and exalted, my days and nights of travel melted under the African sun and the awe-inspiring experience of Collectors Treasury.

Geoff Klass, proprietor of Collectors Treasury (Photos: Tasha Goldberg)

Geoff Klass, proprietor of Collectors Treasury (Photos: Tasha Goldberg)

In this Johannesburg version of Williamsburg, Brooklyn, most businesses are hip with their outdoor seating, traditional fabrics twisted into new styles, and camera crews racing the streets to capture clips of the cool kids. Collectors Treasury is far from any effort to be anything than what it is. Geoff Klass, the owner, as legitimate of a soul you could ask for, is humbly proud of his collections, if not slightly overwhelmed. Even from a young age, he and his brother Jonathan were collectors, and he will be happy to make it clear that some of the items he discovered are not for sale. He keeps the cream of the crop at home, where on a perfect day off, he gets together with his partner and “we play in our large collection of vinyl and books.” He happens to have about 1,500 complete operas on wax, and a flavor for jazz, blues, folk, world music and selected rock. His impressive store has attracted famous musicians and celebrities over the years including Billy Gibson from ZZ Top, who apparently is “such a nice guy,” all the way to Elton John and Catherine Deneuve.

Imagining myself as a movie star in my own drama, I sashayed from room to room, absorbing the intense decibel of silence. Most places I have shopped for records are full of music, yet this warehouse was starkly silent. So bizarre in a way, knowing that with a drop of a needle or crack of a spine, millions of voices would be reciting prayers, poems and promulgations. Botany books stacked on diaries of Anais Nin, history texts leaning against poetry, vintage maps of South Africa with equally old postcards heaped in stacks to the side . . . the collections were endless. Each room led to another room, and each hall was narrowed by towering columns of books and staggering stacks of wax.

At one point, I was invited to the top floor. I climbed into the iron lace elevator, staring as each floor snapped past me with flirtatious heaps of booty. When we landed on Floor 8, I was left to myself and hours floated away. Bits of broken vinyl burrowed into my knees and my neck cracked sideways. In no particular order, Yiddish melodies sat next to Steely Dan, then a pocket of Zulu disco together with reams of classical records. My strategy was to skim spines until I found a cherry, then follow the juice, digging deeper, searching the delights of the tastemaster who dropped off that particular shipment.

When I finally narrowed my stack to a respectable pile, I headed back to Uncle Geoff to check out. Before I reached his little igloo desk area, where there wasn’t even a surface to lay the records flat, he flagged the common themes in my collections and scurried off to bring me more from that vein….and before I knew it I was back in another floor deeper than before. At some point, I had to come out for fresh air. I swore I would return before I left, but the joy in Jozi was everywhere, and I had more to explore.

I found vinyl throughout the city, tucked in nooks and crannies of used book shops and charity shops in Melville. But I found music everywhere. From taxicab drivers to friends in lounges, music is easily a part of life and culture and identity in South Africa. Somehow music, as it always does, extended its hand and brought me in closer to the heartbeat of life and culture in Johannesburg.

Click on above image to listen to "Impi."

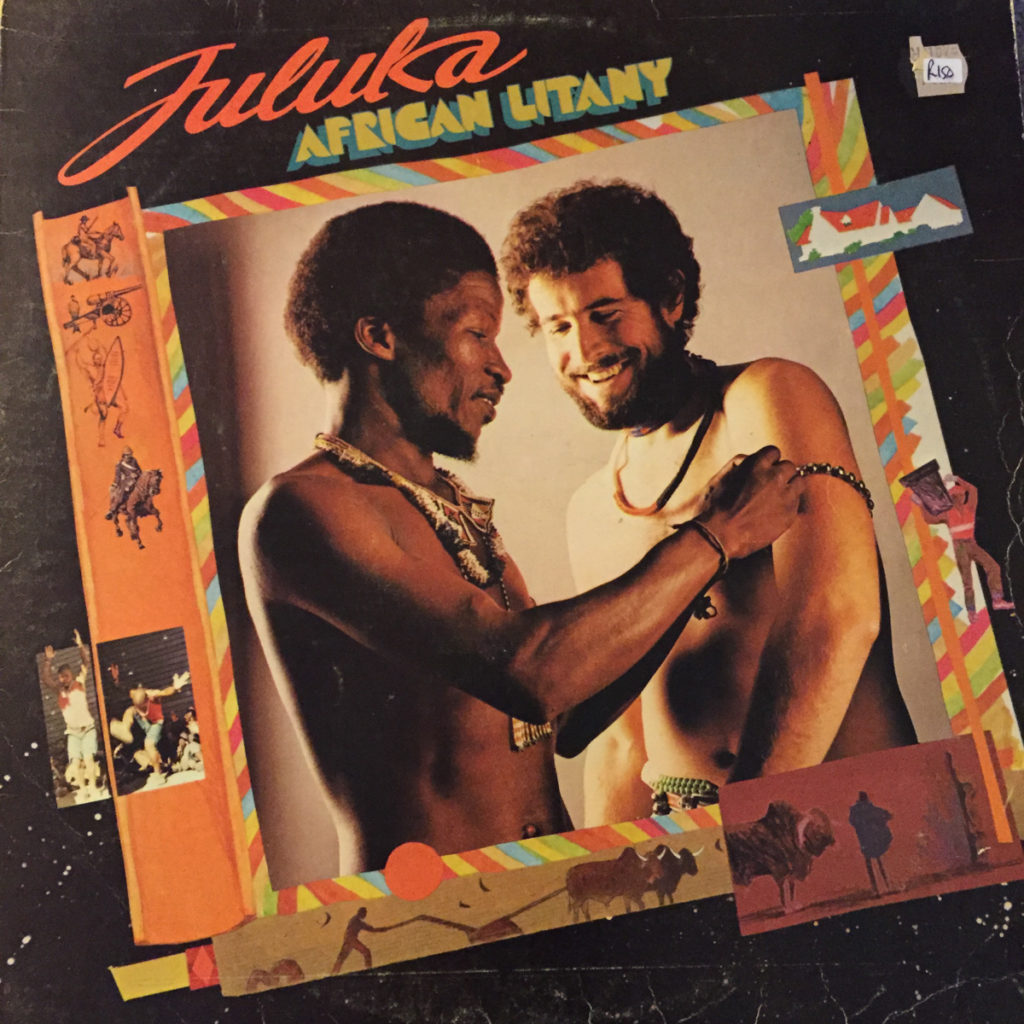

Johannesburg is a cultural hub of southern Africa, attracting not only European and Western interest. When Europeans came to settle in South Africa, the first encounter with the native Zulus occurred at the Battle of Isandlwana in 1879. The Zulus defeated the Anglos, a battle many people reference in music. Johnny Clegg wrote “Impi” in 1981, on Juluku’s album African Litany.

Initially banned from radio as it celebrated a Zulu victory during the then-apartheid climate, it gained so much popularity underground that it ended up becoming somewhat of a national anthem. Today, if you head to a rugby match, you will likely hear this track.

Culture is a constant evolution, and music helps map methodologies of how to hold on to the cord of tradition while braiding nuances from abroad. In addition to attracting western European interest, migrant workers from neighboring countries such as Malawi, Somalia and Zimbabwe come to South Africa. Migration due to conflict, opportunity or adventure, has altered the DNA of culture. A common factor throughout the wide spectrum of music native to South Africa is a consistent theme of maintaining cultural identity and spirituality. Take Zulu gospels for example: Despite the heavy influence of a foreign world view, the most palpable sound is not of the foreigner, it is of the African.

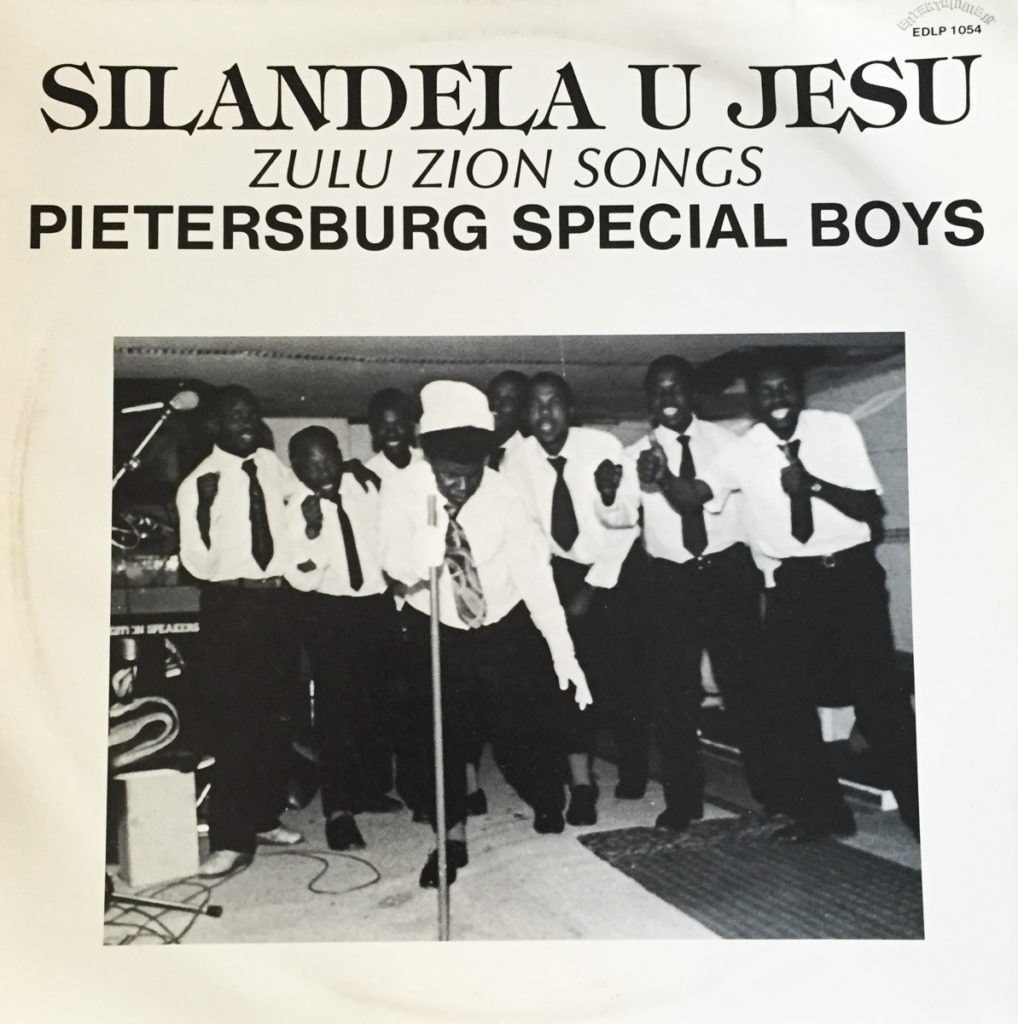

On track three, I Gama Lakho, from Side B of: “Zulu Zion Songs” by the Pietersburg Special Boys, the choir’s sonic styling is more influenced by isicathamiya than anything else. Pietersburg, now called Polokwane, in the Limpopo province, is home to the founder of the Zulu Christian Church, Lekganyane.

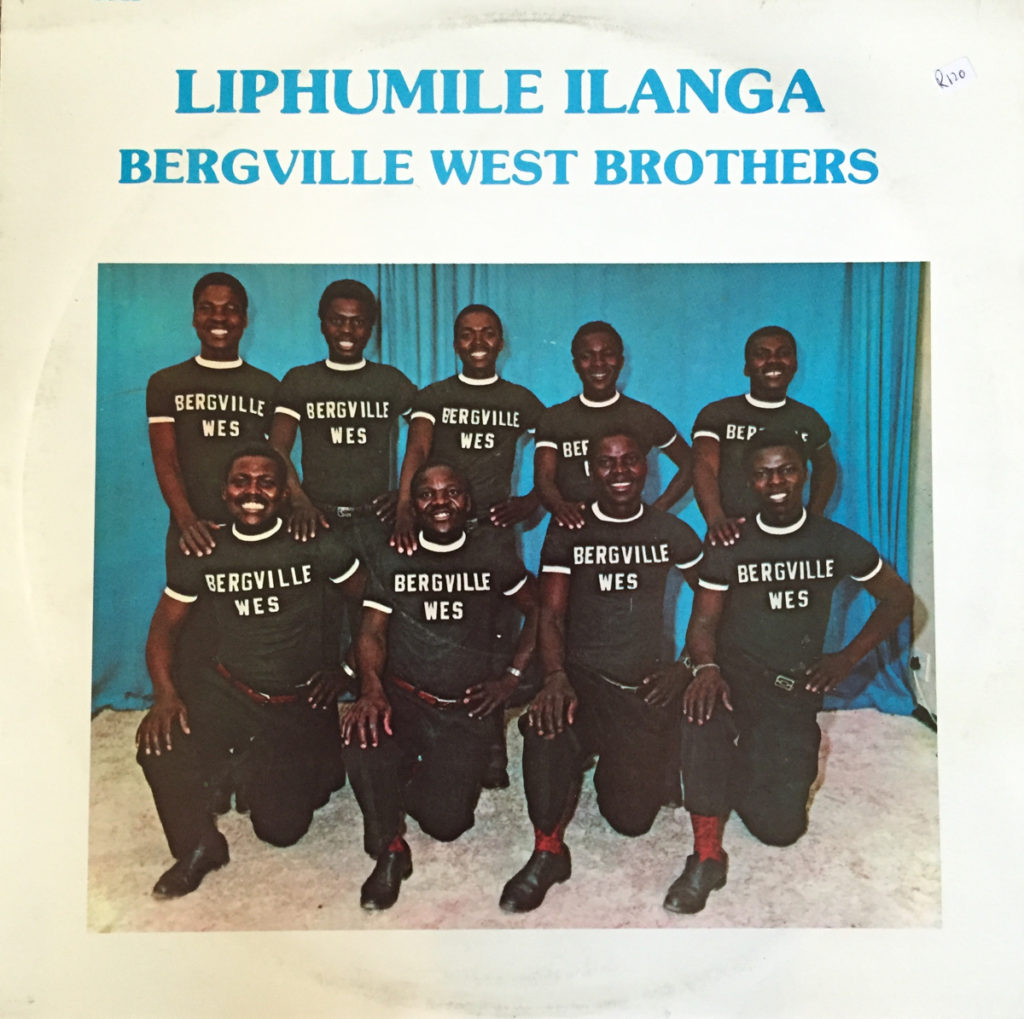

Snippet of Bergville West Brothers

The Bergville West Brothers present a beautiful set of songs on this album. The style of vocal harmonizing, although referred to as rap music on the label, is otherwise called isicathamiya. The soft yet strong singing speaks to the story of migrant workers, who left their homes and families in the country to find work in the city. In a Zulu world view, there is an expression "umuntu, ngumuntu, ngabantu" which means "a person is a person because of other people." Social harmony is embodied by these vocal harmonies. Many migrant workers who lived in dormitory housing, sharing a roof with their bosses, used their voices as a source of entertainment, as well as for expression. The word isicathamiya comes from the Zulu verb, cathama, and describes walking slowly or carefully, hinting to the context of the discretion to which the music was produced in the dorms or hostels.

Ladysmith Black Mambazo helped popularize isicathamiya, bringing the style abroad. However even with the international acclaim, it remains an active form of entertainment and expression in Johannesburg. Each weekend, competitions bring together groups from different areas, to bring their best to their community. In an interview in 2015 with ABC, Mdumxeni Xaba--lead singer of a different group from Bergville, the Bergville Green Lovers--explained, “We sing about our lives, about the community. Many people here don’t have jobs. But when they sing, they don’t think about crime or do bad things. Singing makes us strong…our music is very broad, it tackles many things. We sing about issues of HIV and AIDS, the youth, unemployment, xenophobia, crime–lots of things.”

The migrant worker hostels that birthed the sound of isicathamiya still exist today, and continue to play a role in the social context of Johannesburg. The first housing projects built in 1912, under apartheid rule, were designed to provide housing for black workers who were not allowed to live among white residents. In 1974, Bertha Egnos Godfrey and her daughter Gail Lakier wrote Ipi Tombi, one of the best-known theater productions from South Africa. The show tells the story of a young black man who must leave his village and work in the mines of Johannesburg. The show was loved throughout South Africa as well as Nigeria, Europe, Broadway in the United States, and Canada.

Today, the migrant hostels that house mostly young Zulu men are overcrowded with an average of 11 people sleeping in spaces built for four. The modern social and political challenges that seed in these hostels were part of the inspiration for Bergville Stories, a famous play by Duma ka Ndlovu produced in 1995. In the play, the historical events are linked to the plight of the hostel dwellers, using music and dance to create the story.

Right Now! By Mary Sibande: A local artist expressing perspective on the energy present in Johannesburg.

Right Now! By Mary Sibande: A local artist expressing perspective on the energy present in Johannesburg.

During my stay in Johannesburg, I had a chance to experience first-hand just how relevant music is in unifying and notifying people who are rising up against what they feel is unjust. Nearly every day I was in town, the front page of all newspapers had updates on the national circuit of student protests. The “born-free” generation, those who were born after apartheid ended, were voicing opposition to Blad Nzimande, the higher education minister of South Africa, who announced that universities could set their own fee increases, up to a cap of eight percent. This is not a new focus for the economic freedom fighters that are advocating for free education for all. This summer, South African student, singer and activist Gigi Lamayne introduced Afropop to the plight of the economic freedom fighters that are advocating for free education for all with her song “Fees Will Fall.” Her music became a soapbox to vent and to educate worldwide of reality through the raw black and white cinematography. (See also Afropop Closeups podcast Fees Must Fall: A Voice of Change in South Africa)

With the center of the national protests occurring on Johannesburg’s University of Witswatersand campus, one of the bands leveraging their status to raise awareness of “FEESMUSTFALL,” is the BLK JKS. Gracing the covers of Rolling Stone, Fader, and featured in Pitchfork Media for years, the band has been heralded for its strong uniqueness. The band got some shine from Afropop back in 2009:

On one evening during the student protests, I headed to campus spot, Kitchener’s, to catch a BLK JKS show. As I made my way through the long queue at the door, women called me sister and I felt safe, feeling a sense of solidarity. The cozy venue was brimming with students proudly wearing their university hoodies and slickest styles. The band performed on floor level, instantly giving a feeling of equanimity to the vibe, and the crowd leaned in.

As much as I love vinyl, being at a live show is a whole other environment, a sonic ecosystem. With BLK JKS, they are like curators of a portal, creating a sound that is so complex it becomes simple again. They played through reverb and feedback, and the crowd nodded heads and we moved together. Dipped in their own home brew of velvet underground, BLK JKS gave us a chance to stop talking, and truly converse. After the show, I chopped it up with Mpumemelo Mcata, band guitarist who explained that “when we started, one of our goals was to not be conversational. We played a couple of venues and we saw that people were still talking, and slowly but surely we were like, how do we stop them from talking? Change the beat now, not later, change it now… play it louder, play faster, play slower, you play a quieter song, you play a jazz song, and then it is a little unsettling and off kilter.” The formula works: The band is truly captivating, filling a space with genuine vibrations.

The past is not gone, and if we are lucky, it can guide us in our future. Music makes this possible. Johannesburg has a beautiful musical range, and if you are able to visit, dare yourself to sample from the entire palette.

Stay tuned for part two of "Joy in Jozi," featuring flutes and funk from another social context.