Afropop dives into a celebration of the blues--for some, the essence of the American experience and for others a link back into a lost history in Africa. For our program, we also went back through a number of key interviews we've done in recent years where the subject of blues came up, particularly in reference to the genre's African roots. This feature presents extended excerpts from the interviews we presented on the program, and a few others. [Produced by Banning Eyre, originally aired September 3rd, 2003]

Bonnie Raitt speaking after her trip to Mali with the Afropop team in January, 2000.

Bonnie Raitt speaking after her trip to Mali with the Afropop team in January, 2000.

" I don't speak from an academic point of view. For me, it's all feel, and ever since I first heard Ali Farka Toure when we played together at the Winnipeg [Folk] Festival 15 years ago, and I was turned on to the first batch of Malian music, I was riveted. I absolutely could not believe that something as close to the Delta music [existed in Africa]. The kind of blues that most gets me is Robert Pete Williams, Fred McDowell, Skip James, Son House, John Lee Hooker, the really dark, stark music--and here it was, mirrored back to me, in the music of Ali Farka. So then to go to the country where this is from, having done a little education and reading, and find someone [Lobi Traore] purveying a more modern outcropping of that, keeping one foot in the tradition, very evocative, dark and stark and haunting and lonely and sexy and all those things John Lee Hooker's music brought out of me, to find that also with an almost sunny expression rhythmically on his guitar--it's not a stark sound, not coming from such a painful place--was amazing.

It's an interesting marriage to have dance music and that haunting sound mixed together. It's like what you get in Arabic scales, that particular music from north Africa and the Arabic influence that part of the world has filtered in. That's what made me want to go to Mali.

That type of music, Bambara music, and the way that Lobi plays it, is something that really moves me because its so blues. The thing I like about the blues is the same thing I like about Lobi's playing. And he has a very interesting hybrid of rock and African and blues in him and he is original in a way that I've never heard anybody, his tone and what he plays where and his band is unbelievable.

So it was about as, as--I don't know what the word would be, I don't want to say erotic because that's too limiting-- but powerful in the bigger sense of engaging all your senses. That's the greatest part about rock 'n' roll and music that is rhythmic and [about] nighttime. It is erotic, and it was just resistible. It was also just so freeing for me, and then to have Lobi invite me to sing and play with him, and to go to the depths of the deepest Chicago and Delta blues, it was just the most natural thing in the world--I forgot I was Scottish!

Music in Mali appears to be more of a living, breathing part of the culture, and in a different place, than in America. There's a weird cultural anomaly where middle class white kids pay blues musicians to travel around and play for them. Black middle class, upper class, working class people in urban areas don't flock to blues clubs or buy blues records, so that is a unique sociological institutionalized racism that allows modern black culture to ignore its roots or not particularly like it ,or not honor it because we don't teach about it in school. There's nobody saying, "Why would someone want to listen to BB King? It's their grandparents' or great-grandparents' music." It reminds them of poverty, and an old backwards way before segregation stopped. I understand the sociological reasons why this is basically white people's music here and in Europe, but it's a weird strange bizarre thing, and you can't compare that to a country that owns its own music, and always appreciated its own culture, and celebrates it daily.

It's a moving river--its not a stagnant minstrel show. Not that blues is, but sometimes it can be a money-making thing to put on television to sell beer, commercials, jeans, or any time there is a truck commercial there's a slide guitar…"

Basekou Kouyaté, master ngoni player from Mali, during the recording of Taj Mahal and Toumani Diabaté's Kulanjan album in Athens, Georgia, in 1999.

Basekou Kouyaté, master ngoni player from Mali, during the recording of Taj Mahal and Toumani Diabaté's Kulanjan album in Athens, Georgia, in 1999.

" The blues. I don't know what I can say about the blues, but I adore the blues. There are many types of music in Mali. There is Bambara music, Songhai music, Dogon music, Manding music, Wassoulou music, but what I believe is that Bambara music is the closest to the blues of all. My ears tell me that. It's in the minor pentatonic scale. To me, that's very close to blues. "

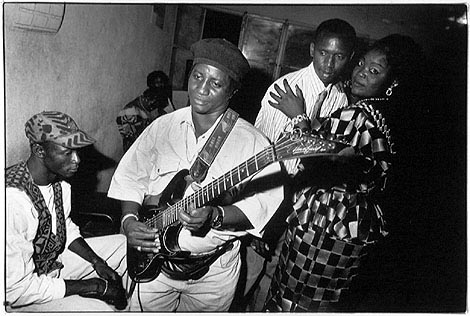

Lobi Traoré, the so-called "Bambara Bluesman," speaking in Bamako, Mali, in 1996.

Lobi Traoré, the so-called "Bambara Bluesman," speaking in Bamako, Mali, in 1996.

" When I was young, before I even knew I would become a musician, I listened to a lot of blues--John Lee Hooker and all that. Maybe I was inspired by it. Maybe the blues was inspired by Africa. Maybe it's just a coincidence. But listen, for me the music I play comes from me, from my place. Someone who hears my music and says it's the blues--well, to me blues is American music. We don't even have that word. Each place has its arts. The blues is nothing but American. If my music resembles the blues, okay. It wasn't me who came up with the idea of Bambara blues. People kept saying, "Bambara blues, Bambara blues." In the end, I accepted it. But I don't think the blues is our music. No. We can play music that resembles it, but the blues is American. We should leave it that way. "

Ali Farka Touré in Boston, 1993.

Ali Farka Touré in Boston, 1993.

" John Lee Hooker plays tunes whose roots he does not understand. He understands the spirit, but it is never Western. Never. It comes from Africa, and particularly from Mali. He talks abut things coming from alcohol, but that's not it. It's the land, nature, animals. The music comes from history. How did it get here? It was stolen from Africans. And Clarence [Gatemouth Brown]: I can teach him things, but he cannot teach me. For ten years, I can teach him African tunes without repeating a note. "

Taj Mahal during the recording of Kulanjan album in Athens, Georgia, in 1999.

Taj Mahal during the recording of Kulanjan album in Athens, Georgia, in 1999.

" The oldest forms of traditional blues that I eventually learned to play came mostly from the culture and records and radio. Many of those people were still traveling around in those days, but I was too young to go and see them. So as I started to play guitar, I made a distinction in the beginning, listening. Because I've always been a listener. There was a way that people played guitar that they played with strumming, and another way that they played with their fingers. I would call this one strumming the guitar, and this one "playing the guitar," because it seemed like you touched each string and made something else happen.

By that time, people like Jimmy Reed and Muddy Waters and Howlin Wolf, and John Lee Hooker were like popular music that you heard. You'd go past somebody's house and you'd smell the fish cooking and the greens cooking, and then you'd hear John Lee Hooker in the background or Muddy Waters. So to me, this represented the music that we developed in this country. I didn't know the old music represented by what Toumani knows. I didn't know the ancient music. I figured I would learn as much of the present day old music as I could because all I was interested in was playing the instrument.

Then my friend Linwood moved next door, so for years, I was playing that Muddy Waters, Jimmy Reed early kind of stuff. He was trying to teach me what now I realize was like Pink Anderson and Blind Blake kind of stuff, and particularly Blind Boy Fuller. That kind of stuff, and the Trice Brothers, and all those guys in what is now termed the Piedmont Area. By then Sonny Terry and Brownie McGee were coming along, and Son House and Skip James. So I just unhooked all that other music and hung out with this music.

Then the big thing for me was that it seemed as though this was a distinct American sound that was developed from an old African sound, which you didn't have many examples of. But the most important example of what it was a couple of songs we recorded where it was clear that the African root was not too far beneath the surface. "Spike Driver's Blues," "Spike Driver's Moan," "Take This Hammer," "The Hammer Blues." This song seemed to get around a lot. That one and "John Henry." Being able to play that well was a very important thing.

There was a club out there called The Ash Grove and that's all they played, nothing but the real deal. I was there all the time. I was the door man; I set the stage up; I set the sound; I tuned people's instruments; I took people to the barber shop and to church. I just got involved on every level that I could, and just sort of stayed home practicing and learning how to play. The rest of it is pretty much history. But the most important link came in the '70s when I'm still trying to get this sound in this "Take This Hammer" song down. That's one song I played every day I don't know for how many years, that and "Freight Train," learning how to steady that sound, and not drop the notes and not drop the melody, or play it any way I wanted to or sing with it. That was important to me.

[In making the Kulanjan album] we all closed the circle. Most people never get to connect the circle. Most black people in America can't even deal with what happened here. If you can't even get back to the blues, you aren't going to get to Africa. "

Corey Harris in two interviews recorded in 2002.

" I always knew that we're from Africa. It was told to me. My mom would tell me. As a kid you ask questions. It wasn't like I grew up in a household that was pan-African, and yet there was a lot of respect for Africa. My mom gave me a poster of Africa. I had it on my wall. It was just a map showing all the resources…In the 70s, it was popular. I had a dashiki. I had an afro. Like that. Fashion things. And of course, hearing some of the music of the era. It couldn't be denied.

For me it was made really explicit, the connection, particularly between Malian music and our music over here when I first started hearing about Ali Farka. I think I read about him first, an article or something. I went out and got the Shanachie record, "African Blues." Woah! Is he even playing a guitar? What is that sound that he's making on there? It doesn't even sound like a guitar. It was beautiful. The rhythms and everything just blew me away.

[Then I actually got to meet Ali and hear him play.] This was at the Jazz Festival in New Orleans. And he had a question and answer session, and people were all asking him about the blues this, the blues that. And he said, "The blues doesn't mean anything to us. Blues is a color. The music I'm playing is very ancient and it's the father to what you do." And people seemed so perplexed by that. They kept asking him questions about his role as an entertainer. And he said, "Well, I'm a farmer. I'm a cultivator. I just happen to play music. I'd rather be home right now. I don't even like traveling."

[Later, Corey traveled to Mali and met a number of musicians there.] It just showed me how many different styles there are. Now I can hear someone from Mali and say, "Oh, he's probably from the south," just by hearing how he plays. Or "That guy is definitely from the north, or Wassoulou region," whereas before I just knew it was generally from Mali somewhere. I have a friend who is actually a nephew of Djelimady Tounkara, Cheick Hamala Diabaté in Maryland. He comes to my town, Charlestown, a lot. It's been a real education meeting everyone. I met Habib and he turned me to some different tunings that I'd never heard and still can't play. And Toumani, of course. It's almost like they're two ends of the spectrum. They're both very contemporary, but Habib is very cutting edge, very modern, and Toumani is like the foundation, the 71st generation or something. So it's real impressive.

It was also just how rhythmic the music [in Mali] is. I always knew that the basis of black music is rhythm, but it was a great demonstration to see all the different ways rhythm comes out. I think even those of us who are really rhythmic in the States only know a few rhythms compared to someone from somewhere else. We also don't know how to pick out a rhythm as well. But play them a rhythm, they know the name of it.…I've noticed that the best musicians are those who played drums or something rhythmic first. Henry Butler is phenomenal. He played drums in church before he ever touched a keyboard. Stevie Wonder, same thing. There are so many examples.

In a lot of traditional ensembles, if you want to play traditional drums in most parts of the continent, they're going to start you out on a bell or a block, or something where you just play a clave, or keep the time somehow, and then you kind of move your way into the drums, rather than you just like jumping up and playing the lead drum. "

Bo Diddley. Speaking of rhythm, when we met the great Bo Diddley at the 2003 Concert of Colors in Detroit, we asked him about his famous backbeat rhythm, so often cited as an example of an African rhythm that resurfaced in the United States.

Bo Diddley. Speaking of rhythm, when we met the great Bo Diddley at the 2003 Concert of Colors in Detroit, we asked him about his famous backbeat rhythm, so often cited as an example of an African rhythm that resurfaced in the United States.

BO DIDDLEY: I don't know nothing about Africa.

[You don't?]

No. But I love that music. I've always liked drum type beats…You see, well, in the Cuban music what they did, they have claves. They had a different thing, a rhythm that they kind of put on top of it.

Now when I when I wrote Bo Diddley, I didn't even have that in mind to do that that way. I just put a drum beat on the guitar with six strings. And what I was trying to do was play Gene Autry's "I Got Spurs, that Jingle, Jangle, Jingle" and I stumbled up on Boom-ba-doom-ba-doom, ba-doo-doo. You know? And that was the beginning of me. That's where it came from. I was trying to play Gene Autry, and made a mistake, I mean a big mistake, cause I didn't know what I was doing period, anyway.

You see, it's one note different. See, "I got spurs that jingle, jangle, jingle." See? "Bo Diddley bought his baby a diamond ring." That's what I was trying to do. So then I stumbled up on that double beat. So I put that dude on all six strings, and there it is. Everybody tries to imitate it, but the don't do it right.

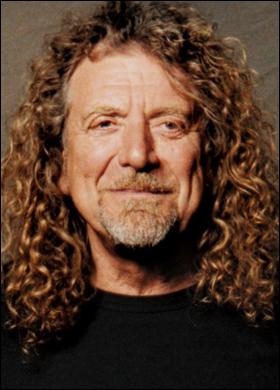

Robert Plant at the Festival in the Desert in Essakane, Mali, January, 2003.

Robert Plant at the Festival in the Desert in Essakane, Mali, January, 2003.

" From 1971 to now, 32 years, I've been traveling in the south of Morocco where the Tuareg are quite prevalent, in a line along with Berber, or "Chleu," south of Marrakech down to Sagora, and the wall that was put up or the fence that Hassan the king erected...So, I was always exposed to this amazing timbre. It was a music that was, not haunting me, but it was reminding me constantly of my youth and my love of Son House and Charlie Patton.

You know, when I was 14 or 15, I was in a very arty environment at school and I was constantly being encouraged by older guys who were always showing me this very archaic African music, which had become a commercial enterprise in America--Paramount Records, OK Records, the Race Records of the late 20's and early 30's, were kind of jolly ditties mixed with some real primal music. When I got to Gulmin, Tantan Tarfaya and into Southern Morocco, I heard the grandfather of this music. And I've been glued to it ever since.

The singers like Tommy McKlennan and Bukka White had this trance-like round when they played the guitar, and you can hear what's going on in the tent next to us: it's so close to Bukka's "Jitter Bug Swing." How many generations is the difference between what we're hearing now and what was recorded by Alan Lomax in 1938-39 in Parchman Penitentiary in Mississippi? I don't know. I mean, I'm a music buff. I'm a collector. I'm a vinyl junkie and I love the blue note. The blue note is everything-- that dipped vocal when you don't expect it and it arrives out of nowhere and it's just like, what is that? Just "aaauuhhh." It's just gone. It just dips down there. You know, I don't care about countries. I don't care about nationalities. I just like that heavenly moment where I learn something. "

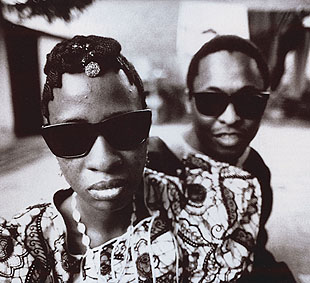

Amadou Bagayogo and Mariam Doumbia of Amadou and Mariam, at the Musiques Mêtises Festival in Angoulême, France, 2002. We asked them to talk about their influences.

" Amadou: In the beginning, I loved all the genres of music. First it was Cuban music. My first songs were Cuban songs. "El Maniscero," "Guantanamera" all that. But afterwards, it was Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton, Led Zepplin, Deep Purple. Lots of groups. Pink Floyd also. Stevie Wonder Ray Charles. Their music seemed a lot like our music. Bambara music. More or less the same thing.

Mariam: Me too. I listened to Jimi Hendrix, Johnny Halliday, Stevie Wonder, many musicians.

[And you also noticed similarities to Bambara music?]

Mariam: Yes, yes, it's almost the same thing.

Amadou: Because when we play, we know that it's the same thing. We have songs that when we play, you would say it's blues. But if you take just the rhythm, it's a rhythm from here as well. "

Amadou Bagayogo and Mariam Doumbia of Amadou and Mariam, at the Musiques Mêtises Festival in Angoulême, France, 2002. We asked them to talk about their influences.

" Amadou: In the beginning, I loved all the genres of music. First it was Cuban music. My first songs were Cuban songs. "El Maniscero," "Guantanamera" all that. But afterwards, it was Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton, Led Zepplin, Deep Purple. Lots of groups. Pink Floyd also. Stevie Wonder Ray Charles. Their music seemed a lot like our music. Bambara music. More or less the same thing.

Mariam: Me too. I listened to Jimi Hendrix, Johnny Halliday, Stevie Wonder, many musicians.

[And you also noticed similarities to Bambara music?]

Mariam: Yes, yes, it's almost the same thing.

Amadou: Because when we play, we know that it's the same thing. We have songs that when we play, you would say it's blues. But if you take just the rhythm, it's a rhythm from here as well. "

FUTHER READINGS

Gerhard Kubik's African and the Blues (Jackson: University Press of Mississipi, 1999)

Robert Palmer's Deep Blues, A Musical and Cultural History of the Mississippi Delta (New York: Penguin Books, 1981)

Dena Epstein's Sinful Tunes and Spirituals (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1977)

John Storm Roberts' Black Music of Two Worlds (Tivoli, N.Y.: Original Music, 1972)

Paul Oliver's Savannah Syncopators: African Retentions in the Blues (New York: Stein and Day, 1970)