Features November 1, 2006

Merengue and Dominican Identity with Paul Austerlitz

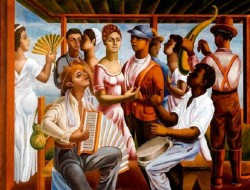

Chances are you’ve heard merengue. You’ve probably experienced something like this: the steady scraping of the guira drives the beat as the pop of the tambora drum begins to weave its tricky rhythm. Suddenly, a slippery saxophone line starts up – you didn’t know people could play that fast – and the full vocals in Spanish rise above the orchestra. You probably couldn’t help tapping your foot, feeling out the sprightly, hip-throwing two-step that has brought merengue to prominence on Latin dance floors everywhere.

But look behind the merengue club craze and the polyester-and-hairgel imagery it evokes and there lies a fascinating story, a long tale of musical evolution that tells of what happens when political turmoil occurs at a true Caribbean cultural crossroads - the Dominican Republic.

This week, Afropop Worldwide talks to jazz musician and ethnomusicologist Paul Austerlitz, author of the definitive history of merengue, Merengue: Dominican Music and Dominican Identity. He first was exposed to merengue when gigging with Latin bands in New York and has since made it the focus of his scholarship. Paul takes us through the history and deeper meaning of this lively Afro-Caribbean dance music.

The Early Years

Chances are you’ve heard merengue. You’ve probably experienced something like this: the steady scraping of the guira drives the beat as the pop of the tambora drum begins to weave its tricky rhythm. Suddenly, a slippery saxophone line starts up – you didn’t know people could play that fast – and the full vocals in Spanish rise above the orchestra. You probably couldn’t help tapping your foot, feeling out the sprightly, hip-throwing two-step that has brought merengue to prominence on Latin dance floors everywhere.

But look behind the merengue club craze and the polyester-and-hairgel imagery it evokes and there lies a fascinating story, a long tale of musical evolution that tells of what happens when political turmoil occurs at a true Caribbean cultural crossroads - the Dominican Republic.

This week, Afropop Worldwide talks to jazz musician and ethnomusicologist Paul Austerlitz, author of the definitive history of merengue, Merengue: Dominican Music and Dominican Identity. He first was exposed to merengue when gigging with Latin bands in New York and has since made it the focus of his scholarship. Paul takes us through the history and deeper meaning of this lively Afro-Caribbean dance music.

The Early Years

Today, the Dominican Republic is a country of 9 million people that shares the Caribbean island of Hispaniola with Haiti. Dominicans, of whom some 800,000 live in New York City, still fondly refer to their country as Quisqueya, the original name of the island given by the Taíno natives who inhabited the island when Columbus first landed their in 1493. Before long, most of the Taínos had been killed and Spanish colonizers imported African slaves to work the sugar plantations. The Africans brought their drums and religious practices with them and incorporated elements of European culture as they intermixed with the Spanish. The result is a culture of syncretism – mixing – which can be seen in vodu, in which African deities are hidden behind Cathlic saints, as well as in Dominican music.

Paul Austerlitz: “Merengue developed as a result of a fusion of

Today, the Dominican Republic is a country of 9 million people that shares the Caribbean island of Hispaniola with Haiti. Dominicans, of whom some 800,000 live in New York City, still fondly refer to their country as Quisqueya, the original name of the island given by the Taíno natives who inhabited the island when Columbus first landed their in 1493. Before long, most of the Taínos had been killed and Spanish colonizers imported African slaves to work the sugar plantations. The Africans brought their drums and religious practices with them and incorporated elements of European culture as they intermixed with the Spanish. The result is a culture of syncretism – mixing – which can be seen in vodu, in which African deities are hidden behind Cathlic saints, as well as in Dominican music.

Paul Austerlitz: “Merengue developed as a result of a fusion of  African influences with the French and Spanish contradanse. So these French and Spanish influences came in, they were blended with African influences and became merengue. Interestingly, merengue in the 19th century was performed throughout the Caribbean , not only in the DR, certainly in Cuba , also Puerto Rico and Venezuela , so it was a pan-Caribbean genre.”

“The most prominent kind of merengue in the DR comes from the Cibao region, in the central part of the country, and it’s called merengue tipico cibaeno, typical merengue from the Cibao region. Merengue tipico cibaeno was originally played with string instruments: guitar and cuatro. The rhythmic accompaniment came from the tambora drum, which is a double-headed drum, and the guira, which is a scraper. In the 1870s, the accordion came into the country and was substituted for the string instruments”

African influences with the French and Spanish contradanse. So these French and Spanish influences came in, they were blended with African influences and became merengue. Interestingly, merengue in the 19th century was performed throughout the Caribbean , not only in the DR, certainly in Cuba , also Puerto Rico and Venezuela , so it was a pan-Caribbean genre.”

“The most prominent kind of merengue in the DR comes from the Cibao region, in the central part of the country, and it’s called merengue tipico cibaeno, typical merengue from the Cibao region. Merengue tipico cibaeno was originally played with string instruments: guitar and cuatro. The rhythmic accompaniment came from the tambora drum, which is a double-headed drum, and the guira, which is a scraper. In the 1870s, the accordion came into the country and was substituted for the string instruments”

After 22 years of rule from neighboring Haiti, the Dominicans finally won independence in 1844. Although the population was mostly of mixed Spanish and African descent, the country was still controlled by European-descended elites. They looked down on merengue as a peasant’s music. But merengue remained popular among the people throughout the 19th century. One of the music’s pioneers during this period was Nico Lora, who is credited with writing thousands of merengues

Paul Austerlitz: Nico Lora was a singer and accordionist and people said he was like a journalist because we would comment on the times. It was said that he could improvise merengues on anything – current events, politics, people could give him a tip and say “improvise a merengue about that girl because I’m trying to date her and I want her to like me, and he would do that and then she’d be impressed”

From 1916 to 1924, American marines occupied the country, bringing jazz with them, a sound that found find its way to merengue.

After 22 years of rule from neighboring Haiti, the Dominicans finally won independence in 1844. Although the population was mostly of mixed Spanish and African descent, the country was still controlled by European-descended elites. They looked down on merengue as a peasant’s music. But merengue remained popular among the people throughout the 19th century. One of the music’s pioneers during this period was Nico Lora, who is credited with writing thousands of merengues

Paul Austerlitz: Nico Lora was a singer and accordionist and people said he was like a journalist because we would comment on the times. It was said that he could improvise merengues on anything – current events, politics, people could give him a tip and say “improvise a merengue about that girl because I’m trying to date her and I want her to like me, and he would do that and then she’d be impressed”

From 1916 to 1924, American marines occupied the country, bringing jazz with them, a sound that found find its way to merengue.

The Dictator who Danced

The Dictator who Danced

In 1930, Rafael Trujillo was elected president, beginning a 31 year rule once called the “most authoritarian dictatorship in Latin America .” He assumed complete control of the nation and did not tolerate any dissent – those that opposed were often assassinated. In addition to being responsible for the deaths of many of his own people, he perpetrated genocide of Haitians, killing between 10,000 to 30,000 who had migrated to the DR for work.

As the same time, bandleader and accordionist Luis Alberti, a skilled musician, was experimenting with using jazz orchestration with merengue, lending the music a softer, “classier” sound. Trujillo , who liked merengue, caught wind of this and decided to use music as a political and social tool.

Paul Austerlitz: He controlled almost all aspects of the Dominican economy, dissent was prohibited, and he also ventured into the area of the arts. And, like Hitler, whom he admired, he knew how powerful the arts and symbolism can be. So he decided that it would be a good idea to bring Luis Alberti’s band to the capital and make it the official dance band of the state. And he did that. And Luis Alberti said yes, because dissent was prohibited, no one was really saying no to anything that Trujillo asked. And the band was renamed “Orquesta Presidente Trujillo .” So in one fell swoop, Trujillo decided that merengue should be the national music of the Dominican Republic. Composers were required to write songs about Trujillo . And many merengues extolled the virtues of his regime.

Trujillo ’s brother, Petán was a music-lover and almost single-handedly controlled music in the Dominican Republic . He owned a radio station called “La Voz Dominicana” that sought out a featured merengue groups, going so far as to pay for the musical education of the musicians who worked for him. But only musicians who were favored by the regime could get any exposure. The biggest merengue star of the time was singer Joseito Mateo, still known as “the King of Merengue.”

In 1930, Rafael Trujillo was elected president, beginning a 31 year rule once called the “most authoritarian dictatorship in Latin America .” He assumed complete control of the nation and did not tolerate any dissent – those that opposed were often assassinated. In addition to being responsible for the deaths of many of his own people, he perpetrated genocide of Haitians, killing between 10,000 to 30,000 who had migrated to the DR for work.

As the same time, bandleader and accordionist Luis Alberti, a skilled musician, was experimenting with using jazz orchestration with merengue, lending the music a softer, “classier” sound. Trujillo , who liked merengue, caught wind of this and decided to use music as a political and social tool.

Paul Austerlitz: He controlled almost all aspects of the Dominican economy, dissent was prohibited, and he also ventured into the area of the arts. And, like Hitler, whom he admired, he knew how powerful the arts and symbolism can be. So he decided that it would be a good idea to bring Luis Alberti’s band to the capital and make it the official dance band of the state. And he did that. And Luis Alberti said yes, because dissent was prohibited, no one was really saying no to anything that Trujillo asked. And the band was renamed “Orquesta Presidente Trujillo .” So in one fell swoop, Trujillo decided that merengue should be the national music of the Dominican Republic. Composers were required to write songs about Trujillo . And many merengues extolled the virtues of his regime.

Trujillo ’s brother, Petán was a music-lover and almost single-handedly controlled music in the Dominican Republic . He owned a radio station called “La Voz Dominicana” that sought out a featured merengue groups, going so far as to pay for the musical education of the musicians who worked for him. But only musicians who were favored by the regime could get any exposure. The biggest merengue star of the time was singer Joseito Mateo, still known as “the King of Merengue.”

Trujillo was assassinated in 1961, leading to a confrontation for succession between members of his regime and leftists led by Juan Bosch. Although Bosch was elected in 1963, he was soon overthrown by the military, causing a civil war. Even though merengue was very closely tied to Trujillo , it became a re-appropriated for the leftist, or Constitutionalist cause. New musicians on the scene such as Johnny Ventura played for the Constitutionalist troops to keep up morale.

The end of the Trujillo regime also led to new creative currents in merengue. With tight government control lifted, musicians had the freedom to respond to the desires of the people. The big band and the accordion were abandoned and replaced with a smaller group that resembled the horn-led bands of salsa. New record labels began to print albums and market merengue music commercially. Despite the political turmoil, people were happy to see Trujillo gone, and this was evident in the music.

Paul Austerlitz: The new merengue was more frank, in addressing the sexual nature of merengue, and it was really happy and fast, and it just grabbed people and expressed the times. Johnny Ventura was actually considered to be the Dominican Elvis, even though the music didn’t really sound like rock n’ roll. It was more like the way he looked and his clothes. It was kind of new, modern merengue that was taking in some elements from rock n’ roll, at least in the stage image, and also from salsa, and was more modern and international.

Trujillo was assassinated in 1961, leading to a confrontation for succession between members of his regime and leftists led by Juan Bosch. Although Bosch was elected in 1963, he was soon overthrown by the military, causing a civil war. Even though merengue was very closely tied to Trujillo , it became a re-appropriated for the leftist, or Constitutionalist cause. New musicians on the scene such as Johnny Ventura played for the Constitutionalist troops to keep up morale.

The end of the Trujillo regime also led to new creative currents in merengue. With tight government control lifted, musicians had the freedom to respond to the desires of the people. The big band and the accordion were abandoned and replaced with a smaller group that resembled the horn-led bands of salsa. New record labels began to print albums and market merengue music commercially. Despite the political turmoil, people were happy to see Trujillo gone, and this was evident in the music.

Paul Austerlitz: The new merengue was more frank, in addressing the sexual nature of merengue, and it was really happy and fast, and it just grabbed people and expressed the times. Johnny Ventura was actually considered to be the Dominican Elvis, even though the music didn’t really sound like rock n’ roll. It was more like the way he looked and his clothes. It was kind of new, modern merengue that was taking in some elements from rock n’ roll, at least in the stage image, and also from salsa, and was more modern and international.

Dominicans talk about that aesthetic of euphoria and exuberance, they often call it “subido” which means “rising”, like “going up” So merengue bandleaders and singers in the hot part of a song will say “Sube!” which means “get up!”, “get down!”, “get even hotter”. Interestingly, in religious music, during ceremonies the hot part of the music, when it’s really getting going and the spirits might manifest themselves in spirit possession, that’s also called subido. That’s the subido reality, that’s when it rises, “sube”. And that’s the central aesthetic, I think, of merengue, and that accounts for its great popularity.

Merengue was brought overseas by Dominican immigrants, mainly in New York and Puerto Rico , who began emigrating in the 60s. As the popularity of salsa among Latino communities waned in the 80s, merengue caught on. To the delight of Dominicans, merengue was catapulted into the position of international pop music. This merengue “boom” was led by a bandleader named Wilfrido Vargas, who was playing an exciting and innovative style. Successive musicians, including Felix de Rosario and Juan Luis Guerra, continued to add their own touches by drawing on jazz, funk, disco, Brazilian music, and other styles, without compromising fundamental merengue rhythm. All-female bands began to be produced and female stars such as Millie Quezada and Belkis Concepcíon emerged.

Dominicans talk about that aesthetic of euphoria and exuberance, they often call it “subido” which means “rising”, like “going up” So merengue bandleaders and singers in the hot part of a song will say “Sube!” which means “get up!”, “get down!”, “get even hotter”. Interestingly, in religious music, during ceremonies the hot part of the music, when it’s really getting going and the spirits might manifest themselves in spirit possession, that’s also called subido. That’s the subido reality, that’s when it rises, “sube”. And that’s the central aesthetic, I think, of merengue, and that accounts for its great popularity.

Merengue was brought overseas by Dominican immigrants, mainly in New York and Puerto Rico , who began emigrating in the 60s. As the popularity of salsa among Latino communities waned in the 80s, merengue caught on. To the delight of Dominicans, merengue was catapulted into the position of international pop music. This merengue “boom” was led by a bandleader named Wilfrido Vargas, who was playing an exciting and innovative style. Successive musicians, including Felix de Rosario and Juan Luis Guerra, continued to add their own touches by drawing on jazz, funk, disco, Brazilian music, and other styles, without compromising fundamental merengue rhythm. All-female bands began to be produced and female stars such as Millie Quezada and Belkis Concepcíon emerged.

Paul Austerlitz: “When I started playing merengue in the 1980s, Central American dancers were always asking for Dominican music. At that time, salsa was in kind of a lull in New York and around the world, there weren’t a lot of really exciting things happening in salsa. Merengue hit the scene, Wilfrido Vargas’ music was playing in the clubs in New York and all over Latin America , it was something fresh and new and it really hit people very strongly.”

“Bandleaders would work with the audience in the moment. It’s improvised music, but not improvised in the jazz sense of creating something really elaborate. It’s improvised in the way an MC improvises in hip-hop or the leader of an Afro-Caribbean religious ceremony, who is also like an MC - orchestrating who’s dancing, what spirits are going to come down. Wilfrido Vargas is a sort of shaman, too, because he would work with the audience and feel what kind of mood they’re in. And improvise things, telling his band to go into particular rhythms or riffs in particular points in his performances”

The international success of merengue has empowered the small island nation, proud to have made such a loud splash.

Paul Austerlitz: “Dominicans are justifiably proud of the way merengue is known all over the world – In Japan people are even playing merengue. I was in Finland and I saw some merengue records in the bins. So, Dominicans often have problems with the border, a lot of Dominicans want to move to the United States but they can’t get in. And the border is not controlled by Dominicans, it’s controlled by the US. People have suffered. Perhaps that physical border is not controlled by Dominicans, but the aesthetic border zone is sometimes controlled by them. Dominicans have used merengue as a way to control the musical border zone, and create a place where these unequal power relationships can be negotiated.”

The African Connection and Dominican Identity

Paul Austerlitz: “When I started playing merengue in the 1980s, Central American dancers were always asking for Dominican music. At that time, salsa was in kind of a lull in New York and around the world, there weren’t a lot of really exciting things happening in salsa. Merengue hit the scene, Wilfrido Vargas’ music was playing in the clubs in New York and all over Latin America , it was something fresh and new and it really hit people very strongly.”

“Bandleaders would work with the audience in the moment. It’s improvised music, but not improvised in the jazz sense of creating something really elaborate. It’s improvised in the way an MC improvises in hip-hop or the leader of an Afro-Caribbean religious ceremony, who is also like an MC - orchestrating who’s dancing, what spirits are going to come down. Wilfrido Vargas is a sort of shaman, too, because he would work with the audience and feel what kind of mood they’re in. And improvise things, telling his band to go into particular rhythms or riffs in particular points in his performances”

The international success of merengue has empowered the small island nation, proud to have made such a loud splash.

Paul Austerlitz: “Dominicans are justifiably proud of the way merengue is known all over the world – In Japan people are even playing merengue. I was in Finland and I saw some merengue records in the bins. So, Dominicans often have problems with the border, a lot of Dominicans want to move to the United States but they can’t get in. And the border is not controlled by Dominicans, it’s controlled by the US. People have suffered. Perhaps that physical border is not controlled by Dominicans, but the aesthetic border zone is sometimes controlled by them. Dominicans have used merengue as a way to control the musical border zone, and create a place where these unequal power relationships can be negotiated.”

The African Connection and Dominican Identity

Paul Austerlitz: “There are people in the DR who will say that merengue is European. But that’s the great paradox of Dominican culture, and Trujillo kind of personified that paradox. This is an Afro-Caribbean country with a very Eurocentric identity. Trujillo personified that, he chose merengue as the national music because he claimed, and his ideologues claimed that it was a European music. But we know that it has African influence. We also know that Trujillo was a very skilled merengue dancer, he loved merengue, and he responded to the African influences in merengue.”

“Merengue does have some European influences, it is a syncretic genre

Paul Austerlitz: “There are people in the DR who will say that merengue is European. But that’s the great paradox of Dominican culture, and Trujillo kind of personified that paradox. This is an Afro-Caribbean country with a very Eurocentric identity. Trujillo personified that, he chose merengue as the national music because he claimed, and his ideologues claimed that it was a European music. But we know that it has African influence. We also know that Trujillo was a very skilled merengue dancer, he loved merengue, and he responded to the African influences in merengue.”

“Merengue does have some European influences, it is a syncretic genre  it’s not totally an African genre. The way that merengue is danced for example, it’s danced in the ballroom dance position, that’s a European form of choreography. Also, traditional merengue has three sections. That sectional form comes from the contradanse which is a European dance.

But we’ve seen that Dominican drums are actually based on African prototypes. Dominican rhythms, like all Afro-Caribbean rhythms and African rhythms are based on a responsorial aesthetic, which means that the aesthetic is based on two instruments or voiced responding to each other, such as call and response in voices with a soloist and chorus responding, or drums talking back and forth with each other. And that responsorial aesthetic extends to the dance, so that you also respond to the music by moving your body. So that's why Dominicans often say that the music is very contagious, it has this contagious quality when you listen to it, it just gets into you."

Indeed, Dominicans have long identified as European, as opposed to “African”

it’s not totally an African genre. The way that merengue is danced for example, it’s danced in the ballroom dance position, that’s a European form of choreography. Also, traditional merengue has three sections. That sectional form comes from the contradanse which is a European dance.

But we’ve seen that Dominican drums are actually based on African prototypes. Dominican rhythms, like all Afro-Caribbean rhythms and African rhythms are based on a responsorial aesthetic, which means that the aesthetic is based on two instruments or voiced responding to each other, such as call and response in voices with a soloist and chorus responding, or drums talking back and forth with each other. And that responsorial aesthetic extends to the dance, so that you also respond to the music by moving your body. So that's why Dominicans often say that the music is very contagious, it has this contagious quality when you listen to it, it just gets into you."

Indeed, Dominicans have long identified as European, as opposed to “African”  Haitians next door. In fact, Trujillo banned vodu practices as well as the associated drumming traditions. More recent musicians have begun to acknowledge the importance of Africa in their music. Juan Luis Guerra, who is fascinated by his African musical roots, recorded a song with Congolese guitarist Diblo Dibala on his album Fogarté to illustrate this.

New Currents In Merengue

Haitians next door. In fact, Trujillo banned vodu practices as well as the associated drumming traditions. More recent musicians have begun to acknowledge the importance of Africa in their music. Juan Luis Guerra, who is fascinated by his African musical roots, recorded a song with Congolese guitarist Diblo Dibala on his album Fogarté to illustrate this.

New Currents In Merengue

We also talked to Angelina Tallaj, an ethnomusicology Ph.D candidate at the CUNY Graduate Center who specializes in Afro-Dominican music. She turned us on to the current trends in merengue.

Angelina Tallaj: So over the last decade, a lot of merengues have borrowed from Afro-Dominican music - more and more than ever before there is a lot of fusion between Afro-Dominican styles and merengue. Also, a lot of merengues made by the second-generation Dominicans in New York City have taken from urban American influences, such as techno, house, and hip-hop.”

Merengue star Kinito Mendez released an album in 2001, A Palo Limpio, which features songs that draw on palos and salve, African-based ceremonial drumming traditions, bringing marginalized music into the spotlight. Another group, Tulile, has songs that combine merengue and gagá, a processional music played by interlocking single-note brass instruments. These are indicators that attitudes towards the DR’s African roots are changing.

Angelina Tallaj: After the popularity of Kinito Mendez, who became extremely popular in discos in New York and then later in the DR, now its not uncommon to go to a disco called to a fiesta de palo, which is rural ensemble of palo drummers, playing religious music, but being danced to in a very secular way and enjoyed by all the disco-goers.

I think attitudes towards Dominican identity is changing, you couldn’t say that it spread to the entire generation, but among the politically progressive and the intellectuals, there is no doubt that the Dominican Republic has as many or more African influences than Spanish ones.”

We also talked to Angelina Tallaj, an ethnomusicology Ph.D candidate at the CUNY Graduate Center who specializes in Afro-Dominican music. She turned us on to the current trends in merengue.

Angelina Tallaj: So over the last decade, a lot of merengues have borrowed from Afro-Dominican music - more and more than ever before there is a lot of fusion between Afro-Dominican styles and merengue. Also, a lot of merengues made by the second-generation Dominicans in New York City have taken from urban American influences, such as techno, house, and hip-hop.”

Merengue star Kinito Mendez released an album in 2001, A Palo Limpio, which features songs that draw on palos and salve, African-based ceremonial drumming traditions, bringing marginalized music into the spotlight. Another group, Tulile, has songs that combine merengue and gagá, a processional music played by interlocking single-note brass instruments. These are indicators that attitudes towards the DR’s African roots are changing.

Angelina Tallaj: After the popularity of Kinito Mendez, who became extremely popular in discos in New York and then later in the DR, now its not uncommon to go to a disco called to a fiesta de palo, which is rural ensemble of palo drummers, playing religious music, but being danced to in a very secular way and enjoyed by all the disco-goers.

I think attitudes towards Dominican identity is changing, you couldn’t say that it spread to the entire generation, but among the politically progressive and the intellectuals, there is no doubt that the Dominican Republic has as many or more African influences than Spanish ones.”

In addition, the current generation of Dominicans, especially those growing up in US cities, have brought hip-hop and techno into the fold, creating the genres of mereng-house and mereng-rap, spearheaded by artists Proyecto Uno and Fulanito, respectively. Angelina explores why African-influenced genres in the DR and abroad have found their way to the Dominican mainstream.

Angelina Tallaj: A big influence has been a kind of Afro-diasporic identity that Dominicans in New York develop. After being in New York for a while, or second generation Dominicans who share schools and neighborhoods with African-Americans have no stigma attached to being black.

I think all Dominicans who come to NYC, including me, no matter how light or dark-skinned, always think of themselves as white, because we are taught that we are European, that only Haitians are black. But I think that when we arrive here, where we are seen as black, I think there's a moment of trauma, and a moment of just really having to reexamine who we are. And I think all these groups from New York, groups that actually take from traditional merengue but fuse it with hip hop, have probably all gone through some sort of similar trauma, and first kind of neglecting all the African stuff, but then really embracing it, and learning to just accept it as part of who they are.

So what does merengue mean to Dominicans, like Angelina, who live in the United States?

I think merengue is a way of empowering us. If the music that represents you becomes wildly popular among non-Dominicans, it’s a way of feeling like you have a voice. People know who you are, we’re not foreigners any more, and we belong to the North American society. It meant a lot for Dominicans when merengue got all the international attention that it did. It makes you feel like you’re on the map.

Paul Austerlitz was interviewed by Sean Barlow in 2006.

In addition, the current generation of Dominicans, especially those growing up in US cities, have brought hip-hop and techno into the fold, creating the genres of mereng-house and mereng-rap, spearheaded by artists Proyecto Uno and Fulanito, respectively. Angelina explores why African-influenced genres in the DR and abroad have found their way to the Dominican mainstream.

Angelina Tallaj: A big influence has been a kind of Afro-diasporic identity that Dominicans in New York develop. After being in New York for a while, or second generation Dominicans who share schools and neighborhoods with African-Americans have no stigma attached to being black.

I think all Dominicans who come to NYC, including me, no matter how light or dark-skinned, always think of themselves as white, because we are taught that we are European, that only Haitians are black. But I think that when we arrive here, where we are seen as black, I think there's a moment of trauma, and a moment of just really having to reexamine who we are. And I think all these groups from New York, groups that actually take from traditional merengue but fuse it with hip hop, have probably all gone through some sort of similar trauma, and first kind of neglecting all the African stuff, but then really embracing it, and learning to just accept it as part of who they are.

So what does merengue mean to Dominicans, like Angelina, who live in the United States?

I think merengue is a way of empowering us. If the music that represents you becomes wildly popular among non-Dominicans, it’s a way of feeling like you have a voice. People know who you are, we’re not foreigners any more, and we belong to the North American society. It meant a lot for Dominicans when merengue got all the international attention that it did. It makes you feel like you’re on the map.

Paul Austerlitz was interviewed by Sean Barlow in 2006.

Ethnomusicologist and jazz composer Paul Austerlitz is the author of two books: Merengue: Dominican Music and Dominican Identity, and Jazz Consciousness: Music, Race, and Humanity. He has also produced two CDs which fuse jazz with Dominican rhythms such as palos and merengue: A Bass Clarinet in Santo Domingo and Detroit , and Global Consciousness Music: Merengue-Palo-Jazz. Check out his site at http://www.paulausterlitz.org

Angelina Tallaj is a pianist and ethnomusicology student who moved to New York from the in the 80s. A Ph.D candidate at the CUNY Graduate Center , she specializes in Afro-Dominican music.

Ethnomusicologist and jazz composer Paul Austerlitz is the author of two books: Merengue: Dominican Music and Dominican Identity, and Jazz Consciousness: Music, Race, and Humanity. He has also produced two CDs which fuse jazz with Dominican rhythms such as palos and merengue: A Bass Clarinet in Santo Domingo and Detroit , and Global Consciousness Music: Merengue-Palo-Jazz. Check out his site at http://www.paulausterlitz.org

Angelina Tallaj is a pianist and ethnomusicology student who moved to New York from the in the 80s. A Ph.D candidate at the CUNY Graduate Center , she specializes in Afro-Dominican music.