Ethnomusicologist, record producer and radio presenter Lucy Durán is a legend of West African music. She began researching in Gambia some 40 years ago, and soon became a major journalistic and scholarly voice on Mande music, especially in Mali, and the roles of women in traditional and contemporary West African music. Lucy was lead presenter for BBC’s World Routes program for its entire 13-year run, all the while keeping up her ongoing teaching position at S.O.A.S. (School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London). Lucy has been a longtime friend of Afropop Worldwide. Her 2012 film project, Growing Into Music, a deep examination of oral transmission in musical families in five countries, inspired Afropop’s Hip Deep program, “Growing Into Music in 21st Century Bamako.” Our research trip to Mali in January and February 2016 included visits to families Lucy worked with before Mali’s 2012-13 crisis. Upon returning from that trip, Banning Eyre debriefed with Lucy, who spoke from the S.O.A.S. radio studio in London. Here’s an edited transcript of their conversation.

Banning Eyre: Welcome, Lucy. It's great to speak with you again. You were just telling me that it's been 30 years since you first went to Mali. Tell us more.

Lucy Duràn: At the end of April 1986, I went to Mali for the first time. I had already spent nearly 10 years working in the Gambia and Senegal, mostly with kora players, mostly with Toumani Diabaté’s great uncle Amadu Bansang Jobarteh, who was my kora teacher. Also with Dembo Konte, Alhaji Bai Konte’s son. So the three of us decided that it was time that we actually went to Mali. Mali was where all the great music was, and where all the ngara, the great master musicians were, and the great women singers especially. And so we got into a bush taxi from Brikama and went as far as Tambacounda, sort of southeast Senegal, and got onto a train to take us to Bamako, because in those days there was no road [from Senegal to Mali]. The only way you could get there was by train.

Unfortunately, we got onto the merchandise instead of the passenger train, so there were no seats and the floors were just covered with women with gigantic baskets of various smelly fish, and cattle and all sorts of things. So it was quite a ride. We spent three or four days in Kayes, and of course April is the hottest month of the year in Mali. And I'm just about to go back, so the same wall of heat is going to hit me.

Anyway, we arrived in Bamako at 3:00 in the morning and it was such a grueling and exhausting trip that Amadu Bansang was so eager to get off that he lost one of his shoes on the train. So we were this completely motley crowd of three bedraggled people arriving at the home of Sidiki Diabaté, Toumani’s father, at the end of April 1986, and that was 30 years ago. That's my story.

Bamako (Eyre 2016)

That bookends quite a saga. I wish you a good 30th anniversary there, and I look forward to hearing about it. But let's go back to the beginning. For our listeners, introduce yourself.

My name is Lucy Durán, and I'm at the School of Oriental and African Studies which is part of the University of London, where I've been since 1992 teaching African, West African and Cuban music and a few other courses. I have this history of nearly 40 years now of involvement with Mande music. It was through my Gambian connections that I met Toumani Diabaté, whose first six albums I produced, and also his last one with his son Sidiki. I know all his family very well. I knew his father, the so-called "king of the kora,” very well. The late Sidiki was a fine man and an amazing musician. So I would say I’ve been immersed in Mande griot music for most of my professional life.

The radio program we’re producing looks at the way traditional musical families are functioning in Mali with all the changes that society is now facing. It was inspired by your Growing Into Music film project. Tell us about that.

In 2009, I started Growing Into Music, looking at musical acculturation in oral traditions. It was a project that covered five different countries: India, Azerbaijan, Mali, Venezuela and Cuba. I was working with a team of three other specialists. The idea was to look at the state of play with oral transmission of musical genres, within specialist musical families, such as North Indian classical music, or Azerbaijani mugham, or in the case of Mali, Mande griots’ music.

We tend to think of there being a conflict between written transmission and oral transmission, so the idea that in northern India, more and more music is being taught in schools raises the question: how does writing things down affect the tradition? Will oral tradition continue? I spent a lot of time between 2009 and 2012 in Mali, and a little bit in neighboring Guinea, working with about 10 different families of celebrated griots, or Mande jeliw, these hereditary musicians, or this casted lineage of musicians ,if you like.

I was filming the way that children were actually learning, and the context in which they learned. In some cases, they would be having a kind of a lesson, but mostly it would be more informal, almost like small performances in the home where they would be corrected, in some cases encouraged, and sometimes laughed at by their peers. These were all ways in which they would learn. Sometimes they would hear older children in the family doing something and then they would strive to imitate them. A lot of the learning came through imitation and osmosis.

Khalifa Diarra, on balafon (Eyre 2016)

There were a number of questions I was interested in. What relationship did the more informal and older forms of transmission have with the media, with learning from television and radio and recordings? And what kind of tensions might there be between griot children going to school, and griot children from an early age beginning to perform at wedding parties, which is really the main context these days in which real music is performed? So these were interesting aspects of the work, but hard to document. How do you actually document the process of growing into music? It's almost like documenting growing into language. You would have to be a fly on the wall the entire time to see progress.

We tried to follow specific children over a period of three years, and watch their progress. Some of them made quantum leaps in the three years, and others just treaded water and didn't seem to get anywhere.

One thing that was of particular interest to me was that I did not want to look just at the brilliantly talented, those special virtuosic children. I knew that Mande jeli families felt that they had an obligation to teach all their children, or grandchildren, or children in the extended family—they all needed to know some of the basic skills of the performance of jeli music. They didn't single out the particularly talented ones. There was no special help for those who were particularly talented. But there's a moment when some children just drop out because they're not interested, they're not motivated, or they're just not talented, even though they're all within griot families. So that's what you can see in the films Growing Into Music, which cover the years from 2009 to 2012.

Fantastic. For our purposes, we are going to focus on a three brilliantly virtuosic children.

Sure. And of course, ultimately it was the virtuosic ones that really interested me. But there are so many television programs about musical children that focus on gifted children. I felt that in griot families, you need to look beyond the ones that are obviously gifted. And sometimes the obviously gifted ones don't stay with music.

Let's start with Ami Diabaté. We interviewed her with her father, Lassi. Introduce them for us. Tell listeners who we’re going to meet in this radio program.

We’re going to meet two generations in the family of the late Bako Dagnon, who was probably Mali’s greatest female singer of the late 20th century, early 21st century. She died in July 2015, quite young, 62. She was a marvelous singer, and one of her sons, Lassi Diabaté, is a fabulous, virtuosic guitarist. He has grown up absolutely embedded and immersed in the griot tradition, and his daughter Ami is now 12 years old. I first started filming Ami when she was five years old, and it was clear from the moment I met her that this was an extraordinary little girl with a beautiful voice, and a fantastic memory for the griot tradition. Ami will undoubtedly be one of the great female stars of the future in Mali.

Ami Diabate and her father Lassi Diabate (Eyre 2016)

Ami is wonderful, as you say, and quite charming too. Let's introduce the other young musicians we’re going to meet. These are students of and co-collaborators with a rather different maestro, Adama Diarra.

This is a musician I've known for many years in Mali. Adama Diarra is a percussionist. He is also a griot, but he’s actually not Mande. He is Bobo, which is another ethnicity found more in the southeast of Mali. But like many Bobo griots, he is very much integrated into the circle of griot activity and musical life in Bamako, and so he plays both Bobo and Mande repertoire. And, although he's an amazing djembe player, he is a multi-instrumentalist. He plays balafon brilliantly, both Bobo and Mande balafon. He can sing; he can play the kora; he makes his own instruments. He's a hands-on, extremely creative and much in-demand musician who plays with many of the best-known stars in Mali, including Babani Koné.

Adama is also an extremely warm character. He's very good with children and great at passing on musical skills because he’s so encouraging and demonstrative. He has a big extended family. Many of them live in Segou and Sikasso and in the provinces, and during school holidays, relatives tend to send their children—boys and girls—to stay with Adama because they know they are going to get really excellent exposure to music and to different musical instruments. They learn to dance and sing and count rhythms. So he is always working with a fluid group of children from his extended family, many of whom are Bobo, which is nice because it means they bring in a different kind of regional and ethnic flavor to their music. In Bamako, griot music is pretty much Mande dominated.

Adama Diarra and young musicians (Eyre 2016)

Adama has got two little boys in his group who really stand out. The older one is Daniel Dembélé, who is Adama’s nephew from Segou, also Bobo. Daniel is a serious, dedicated, brilliant balafon player, whom I first started working with when he was just five years old. Actually, we took him to Cuba last year. We took him with three other Malian children, and the great balafon player Lasana Diabaté. It was an exchange visit. But that’s another story…

Then there is the younger boy, Waly Coulibaly, who is just phenomenal. He lives, breathes, eats balafon. He’s just a complete natural, and every time I would be working with him and with Adama, there would be a point when Adama would say, "O.K., cut the rehearsal. Let’s all go and eat." And Waly would just go on playing. Adama would have to go up to him and say, "Waly, stop playing. You need to rest." This is just a boy who was obsessed with the balafon from the age of 6, and he's absolutely brilliant.

Daniel Dembele and Waly Coulibaly

Daniel Dembele and Waly Coulibaly

That’s for sure. Those two kids really knocked us out. They’ll be stars in our program. Let’s talk about the different kinds of education in these kids’ lives: griot education versus school. I asked both Lassi and Adama, what is it important that kids learn in school? And the best answer I ever got was language. They need to learn how to communicate. Never was there a sense that they have to learn about science and literature or things like that.

Because you don't learn those things in Malian state school. It is unbelievable.

You’re confirming something we’ve heard a lot about: the terrible state of education in Mali. And of course this is a disaster for the future.

Exactly. The schools do not hold the attention of the students unless their parents have enough money to send them to a private school. Bassekou Kouyaté sends all of his children to a private school. They have learned good French and they can read and write. But Hawa, Kasse Mady’s daughter, cannot afford to send her children to private school yet. So they don't speak French. They can barely read. At age 14, they can barely write their names. And that is the level of education in Mali, I’m sorry to say.

This is a big subject, beyond the scope of this program. But I would like to hear your thoughts about the dilemma that these families face when they have very talented musical children, but there becomes a conflict between musical training and going to school. For example, when we visited Lassi and Ami, I sat and played guitar with Lassi for quite a while, while we waited for Ami to come home from school. It was clearly important to him that she go to school.

Well, there is a long and interesting relationship with griots and Western-style education. Back in the colonial days, the French colonizers insisting on every family sending one member of their family to Western-style school. But many did not want to send their own children to these schools because they believed they would get bad ideas, that they would be influenced by kind of progressive Western ideas, and especially Christianity. So they would send the child of their griot. That’s why many of the best-educated people—and this is true in Senegal as well, in the whole of French West Africa—were griots. So there is a history of griots going to school.

Education is traditionally done by rote, by imitation. The teacher says a phrase and you have to repeat it. Or it’s dictation. And griots are really good at that, because that's how they learn within the families, so they do very well at school. That's the other interesting factor in all this. Let's take the example of Bassekou Kouyaté, the ngoni player, who is now very successful, and whose first solo albums I produced. I spent a lot of time and filmed in his village, Garana. Bassekou told me that his father didn't want him to go to Western school because he didn't want his mind to be corrupted by Western ideology. So Bassekou was prevented from going to school, and he feels hampered by not being able to read and write. So he and his brothers, who also did not go to school, are absolutely determined that all their children should go to school.

There is a moment in Growing Into Music when I put this to his older brother, who lives in Garana and who is one of the "teachers" of ngoni among the extended family. I asked, "How do you feel about your children going to school?" And he says, "School is really important, and it does not damage our ability to memorize our great oral histories. On the contrary, it just enhances our ability to do things, and it means we can move in both worlds. Our children must go to school."

So there is that idea. And then, increasingly, some jelis, like the singer Babani Koné, or the balafon player Lassana Diabaté, prefer their children just to have a good, Western-style education. They do not actually want them to go into music because they are afraid. Where is this music going to go? There is no government support for it. How are their children going to earn money unless they have the great fortune to have an international career? So there is a sense that in the old days, there was a conflict between Western education and griotism, the art of the griot. Nowadays, most griots think that their children must have a Western education, even at the expense of music.

Meanwhile, it is true that if you go to school, you get up early, and you are pretty much all day at school. You spend long hours in school. There is no music at school at all. So if you are learning to play the kora, like Toumani Diabaté’s nephew in the film Growing Into Music, Salif, the young Salif Diabaté—he would get back from school which was across town. He went to a private school. You get back at five in the afternoon, exhausted. He'd been out since seven in the morning. He didn't want to practice the kora. So holidays are the only times when children can make real musical progress. And then you've got long periods were they’re not playing music at all. So there are some sort of areas of conflict and tension between Western-style education and learning to be a jeli within the oral tradition.

Bamako school (Eyre 2016)

There’s a major theme running through the interviews we did with griots in Mali, and that’s this idea of the authentic griot, the “real, real griot” as they say. The ngoni player Ousmane Dagno, like his aunt Bako Dagnon, believes deeply in a pure, uncorrupted form of jeliya found in villages like Golobladji, where he grew up, but not in Bamako. Ousmane says, “Here in Bamako, there is no real jeliya. The real, real griotism, that is something you find in Golobladji. There, we practice the art as in the past. If this person is my jatigui [patron], his child will be the jatigui of my child. But here in Bamako, people need money. They don't need dignity. There is no dignity in Bamako. Everyone is here because of money.”

Well, virtually every Mande griot that I have spoken to from the older generation echoes those views. Every elder jeli has said to me, “The essence, the real essence of jeliya, the art of the jeli, has vanished. If you want to find the great masters, the ngara, as they call them, if you want to find the great ngara, you have to go to the cemetery. They are all dead.”

Why is griotism, real jeliya, dead? Essentially, it is because the relationship between the jeli, the griot, and the jatigui, the patron, has dissipated. It’s become corrupt. And it was that relationship that sustained griots for centuries. It was the patronage of the nobility to the griot—that's what kept them going financially. That's what gave them a base to live and be fed. But also, there was a symbiotic relationship between the griot and the patron. The griot had all the knowledge of the patron’s background—their ancestors and the kinds of battles that they fought, who they had been married to, who they had alliances with—and all this was based on a really deep knowledge that was handed down from one generation to the next, and there was a lot of integrity in that relationship.

It was an equal relationship because the griot was not a noble person, but the griot had such valuable information that he was highly valued. What has happened in the city, in Bamako, and in other urban contexts throughout the whole Mande world, these older relationships between griot and patron have not lasted. It has been difficult to sustain them in many cases. Very often, the griot has a lot more money than the patron, so there's an interesting kind of reversal. The griot can have more power than the patron nowadays. The patron might be the 12th generation descendent of a precolonial clan, but the patron nowadays sweeps the streets in Paris. That is his job. Or her job. Whereas the griot, who is a 12th generation descendent of that patron’s griot, is performing at Carnegie Hall and the Barbican in London, and earning really good fees.

Tiekoro and Ousmane Dagno (Eyre 2016)

Amazing.

So things have changed, and at the heart of that change, and the belief about what has gone wrong, is the dissolution of this close relationship between patron and griot in which there was a lot of dignity, and the griot would not dare lie. A griot did not lie, and nor did the patron lie to the griot, because they knew their stories. So you could trust the griot, and the griot could trust the patron. And all of that has pretty much gone, except in a few cases. So nowadays, if you play at a wedding party, it's because you have a nice voice, not because you have any relationship with either of the families getting married.

So you just do your research. O.K., who is getting married? Miss Diallo is marrying Mr. Toure. So we all know the praise names of Diallo. Diallo jeri, fula horon. And that kind of thing. And Toure. Toure ngana mande mori. All you need to do is a bit of research, find out something about the families, which they do via another griot who is closer to that family. They write it all down. They write down the names of the people who need to be sung for, the godmothers of the wedding, and all this kind of thing. And then they sing their songs for them, and they make huge amounts of money, or can make huge amounts of money, just by singing a song about someone that they've never even met. And that person comes over and starts throwing bills, sometimes large bills: 5,000 CFA, 10,000 CFA. And what does this have to do with real knowledge, long knowledge based on generations together, and all that kind of integrity and dignity?

Dambeya. That's what they call dignity. These are values that are really part of the reason that griotism has continued for so long. And this is going away. There is no doubt about it. I mean you still find someone like Kasse Mady Diabaté—he still has his relationships with his patrons, and those relationships have been going on for generations. For instance, Kasse Mady goes to Paris. Who does he stay with? His patrons. He may be sleeping on a mattress on the floor. They may be poorer than him, but they still have that bond. It's a real bond, and an equal bond. But these relationships are very hard to come by now.

Bako Dagnon

That is so interesting. You know, there was an idea that came out in a couple of the interviews we did in Bamako. There was a claim that people from other ethnic groups, who are not even griots, but who sing well and know the routine, so they will get hired to play at weddings as if they were griots. Is that something you’ve encountered?

There is a bit of tension now between another type of musician, a sort of self-described musician, not a jeli. This is a musician not been born into a lineage of jelis. They call themselves artistes, by which they are trying to say that they are not obliged to perform griotism. If you are born to a jeli lineage, even if you're not musical, you are still seen as a griot, and you still have obligations and that role in society. But these artistes who have been drawn to music because they love it, or they have a natural talent. Sometimes they call themselves songbirds, as in Wassoulou, someone like Oumou Sangaré. These musicians are sometimes asked to play at wedding parties. Very often, they don't charge nearly as much as griots. It is a different type of music for a different type of wedding party.

So more and more, there is a kind of backlash against the griots. The good ones make a lot of money and won't perform for no money, which is not how it should be. That's out of the paradigm of the moral values of the true griot. But these artistes, they don't have set fees.

Musicians at Bamako sumu (Eyre 2016)

Musicians at Bamako sumu (Eyre 2016)

Then there is a whole new category of musicians now called zigiri men. They performed the zigiri, which is based on the zikr. So they are performing much more within the kind of idea of Islamic religious music, or at least the Islamic religious framework. But they are often singing almost exactly like the griots. They are singing at wedding parties, and they also have their list of names of people that they have to sing songs for. But in the middle of it all they will be singing the shahada, you know, “lahi lahilala.” They will be singing a lot of stuff from the Koran.

So these zigiri men are cheap to hire, and more and more, it's them and artistes, and the griots are being pushed out of their circuit—and that is the circuit where they earn their bread and butter. So I think there is a lot of tension between the griots and these artistes. So if you stop doing your griot music, and start doing other types of things, and you wander off, you are moving into the world of artistes. You are moving away from the world of griots.

On the other hand, you can say this is a good thing. It is a good thing that there are now successful artists in Mali. They are challenging the monopoly of griots, and this has really been going on since the late 1980s with the rise of Wassoulou and the new democratic government that came in 1992, after the coup that deposed Moussa Traore, Mali’s second president. So you could see it as a way of democratizing society, and opening society up and moving away from these castes and lineages of artisans that the griots represent. So there are two sides of the argument. But there is definitely tension there.

A jelimuso (female griot) singing at a Bamako sumu (Eyre 2016)

This distinction between the griot and the artiste is something I've heard about ever since I first went to Mali in 1993. But you’ve added some interesting new dimensions to it. I had not heard of these zigiri men.

Zikr is the shahada. You chant and go into a kind of trance. But zigiri as a genre in Mali is interesting. It is new. It's only been around for about 30 years. It is extremely eclectic. I have heard zigiri that is based on the sound of hunter's music, which is ironic because hunters are anything but mainstream Muslim. But zigiri men also do the griot style music. Now you even find zigiri women, who are Wahhabis. They’re completely covered with a down-to-the-floor veil, but they are singing and swaying and rocking to the music. And they have audiences of hundreds of women, all Wahhabis, all in their veils. It's like Mali cannot exist without music, so they're always going to find a way of performing music. You can try to put it into a religious framework or whatever.

So all of this slightly threatens the position that the griots have always had, this very central position, almost like a monopoly in musical life. And it is true that if you go outside the world of griots, and you go into the world of artistes, not many of them have a great sense of training their children. So a lot of the children are just not learning any music at all within the families of these artistes.

There’s one other thing about this whole business of singing people at weddings. Ousmane Dagno also spoke about the near-sacred relationship between the griot and the noble family, as you have here. But I wondered if going to a wedding and just singing about everyone present was in some way a distortion of that. He replied that that was fine, but it seemed like a bit of a contradiction to me. Maybe the answer is that the “real, real griot” actually knows all the families at the wedding because they would have been involved in the all the preparations.

Exactly. For a wedding party, a griot would be invited to perform at the celebration of his or her patron, or member of the extended family. The invitation comes because of that relationship. They may not be a great singer, but their sister or their cousin might be a great singer. So they bring their cousin along, and the cousin sings. This is how it should be. And that family knowledge is already there. They are already intimate with at least one member of the couple’s families. And then they would have to sing songs for the other member of the couple, the bride's family, or the groom's family. The griot has been involved in the whole process of negotiating whom their patron’s daughter marries. So they have been involved right from the beginning. They have done their research already by the time you get the wedding celebration.

So, whereas Babani Koné, who I admire and like very much, and she has a real knowledge of jeliya as well—but you know, people want to invite her to their wedding because she's a big star. So it's kudos for them. It shows that they have money, power and influence, and they know that all the media are going to swoop down on their wedding party, and film Babani Koné because she is such a star. It will be shown on television and then, you know, the godmother, or the person who arranges the wedding party, will be shown over and over again at the wedding party with all her jewels and her finery, giving money to Babani Koné.

So you see what I mean. It is very tempting just say, “To hell with the person who is your griot. I don't want them at my wedding party. I want the big star.” And that big star doesn't have a relationship with your family. So they're just singing n’importe quoi [whatever]. So that is the difference. Ousmane is not contradicting himself.

Master Soumi (Eyre 2016)

I want to ask about the aspect of griot tradition that has to do with truth telling. In the past, griots were licensed to, and indeed responsible for, pointing out when patrons and leaders were making wrong choices. This is a responsibility of the griot tradition that some rappers in West Africa now say that they are assuming, because the griot is too busy looking for money. Mali’s most political rapper, Master Soumi, made a particularly strong statement about this. First of all, his critique of how griots operate in Bamako these days was very similar to Ousmane’s—a real indictment.

Exactly.

That was interesting. And I presented Ousmane with this idea that the griots should be pointing out the incredible corruption that's been going on at the governmental level. I asked him about the events of 2012, the coup d'état in particular, and he commented rather obliquely. He didn't seem to want to get into it. What you make of that?

Well, it's a very, very complex issue. Because there are many ways you can criticize without actually saying things in black and white. And griots are good at that. They will find subtle ways, or they will use proverbs, which, if you are in any way vulnerable or you have done something corrupt, you will understand what they are talking about. About you! So, for instance, there is the song "Bani,” [Sings] This is a very well-known song that a lot of people start to learn when they play the kora. That is their first song. There is a lovely line in that song which goes, “What is bad about power, what destroys the good part of power is someone who doesn't keep his word." It says literally, "Someone who has two words." So you say one thing, and do another. So that's what happens when you get into power. You don't keep your word.

How many politicians can I think of that say, "When I get elected I will do this and I will do that, taxes will be cut and so on?" And then they get into power and they don't do that. They raise student fees instead. That's what they're doing in this country [the U.K.]. And so, I wish a bloody griot would sing that song to them. “You are exploiting your position of power and you are not keeping your word. You must keep your word.” That's what a good leader does. You keep your word.

So there are lots of ways that the griots can be critical, and they have many such phrases in their songs. Now as for 2012, I don't think that Ousmane would have felt comfortable talking about the coup, in particular to a journalist without knowing how it was going to appear, how you might cut up the interview, or where it was going to be heard. So I can see that he wouldn't feel comfortable commenting on that. Just as in your Master Soumi interview, Soumi is not comfortable critiquing Imam Dicko, the conservative Islamic leader.

There are just certain areas that, even if you are the most radical rapper, you will not talk about. Because actually, it is dangerous. That's the problem. The situation since Mali’s coup of 2012 has not at all been resolved. That coup opened a can of worms and Mali is swimming around in that can right now, very unfortunately. So he's not going to talk about that.

Master Soumi at Dogon Cultural Festival (Eyre 2016)

We’ll come back to Imam Dicko. But I want stay with this idea of criticizing political leaders. Sidiki Diabaté, Toumani’s super-popular musician son, had a response that was similar to what you have just said. He basically said, "Well, we can say to the president, ‘Think about what the great leaders of the past did and reflect on whether what you are doing lines up next to that.’" His point was that we griots don’t have to come right out and criticize directly, like those rappers do, but we accomplish the same thing. I still wonder how much that actually happens, how many griots actually had the courage to condemn the coup. But I respect Sidiki’s answer.

Toumani and Sidiki Diabate with Symmetric Orchestra at Festival Acoustic de Bamako (Eyre 2016)

Let’s focus on Sidiki and Toumani for a moment. In our interview, Sidiki speaks about his family's relationship with the Niang family. He takes it back a few generations, basically making the point that the tradition is continuing as in the past. His grandfather and father had patrons in that family, and now, so does he. It is a lasting relationship between families that spans generations. Now, Ousmane said flat out, "Sidiki is an artiste, no longer a griot, and he learned this from his father, Toumani." That’s a pretty hard line.

Toumani Diabaté’s family is fascinating, but they are also quite complicated in terms of how they fit into the framework of griot life in Mali. It’s partly because they are foreigners. Toumani’s father was from Gambia. His grandfather was originally from Galen, near Kita in Mali. But there had been two generations at least living in Gambia, and by the time Toumani’s father, old Sidiki, arrived in Mali in the late 1940s, he had been brought up in Gambia. He spoke Mandinka; he did not speak Bambara. And right up until his death, when Sidiki did speak Bambara, he spoke it with a strong Mandinka accent. You could tell straight away that he was not a Bamana speaker.

So they fit slightly uncomfortably in some ways into society in Mali. They were interlopers; their true patrons were back in the Gambia. So the Niang family—I don't actually know about them in particular. But I think the family forged new alliances and new patrons when they came to Mali from Gambia. But in contrast, Bako Dagnon’s family tree goes back generations and generations in the Golobladji region. And this is such an interesting area from a musical point of view. With Biriko, which is half Fula and half Mande. It’s such a fabulous font of melody. Just amazing. But, you know, Bako goes back many generations living in this rural area whereas Sidiki was a traveler, a wanderer. He left Gambia and installed himself and Mali. And this could well be what’s behind Ousmane’s discourse.

What Ousmane says about griots is almost identical to his aunt Bako Dagnon’s discourse. And it is centered around the relationship, the traditional relationship between patron and jeli, going back generations. Toumani has forged his own relationships with marabouts. And of course he has some patrons, but they are not people who go back generations. So maybe in some ways young Sidiki, Toumani’s son—brilliant musician, by the way—is seeking to validate his own relationships of patronage, even though they may not have been there for generations.

But here’s the key point. Every time you hear someone say, “The real griot doesn't exist anymore. Real griotism, and the real values of the griot have been lost,” it is not to do with how well they play music, or what songs they sing. It is to do with the relationship with a patron. That is the complaint. And the relationship to money. Bako Dagnon would say, "I never sing for money. If my jatigui decides to give me something, they can give it to me. But I do not sing for money. Nobody pays me anything." Even in Mandinka, you don’t say ka jeli djo, “to pay a jeli,” you say ka jeli so—“to give a gift to a jeli.” You never pay a jeli. Never. You present a gift to a jeli.

So the idea of giving a jeli a fee to perform on stage, or a fee to perform at your wedding, when you don't have any relationship with the person who is the host, has just got nothing to do with the real art of the jeli. I think that is at the heart of it all.

Young Sidiki also said that in our interview. “I don't do it for money. But if someone wants to give me money…” But I’m glad you pointed out that this is not about the kind of music you play, because after hearing all this hardline stuff from Ousmane, I was kind of surprised when I went to hear his group in a club, and they were playing this fascinating mixture of styles. It was great, but it did not have much to do with griot tradition. I think I was confusing the whole question of “the artiste versus the griot” as being a question of musical style. But it's really not about that. So he can be a pure griot like his aunt Bako, and then go out on a Friday night and play fusion music. There's no contradiction there at all.

No. I don't think so. Absolutely. Now I personally, Lucy Durán, music producer, I am particularly interested in what I think of as traditional repertoire and traditional ways of playing. And I am very concerned that those should not be lost, because I think there are very beautiful, special and unique traditional pieces. I have listened to that music for nearly 40 years and never tired of it. I have played it as well, and produced it. So I have a special interest in the tradition.

But someone like Ousmane Dagno was brought up in a very traditional environment in Golobladji, where I have been and filmed for Growing Into Music. There is no electricity and no running water. It is rural, basic village life. So they are playing without microphones. They have little transistor radios, but that's it. No television. So he really was brought up in that way. He knows the tradition very well, the stories of all the songs and so on. So when he gets to Bamako, he knows who he is. He knows his background. He knows his value as a member of that wonderful family, the Dagnons. But that doesn't stop him from experimenting and playing many different kinds of music. It has almost got nothing to do with it. What you play has got nothing to do with it. It is your personal moral values, and not groveling for money, and continuing to have a relationship with the family of your traditional patron.

Ousmane Dagno (center) with his nightclub ensemble (Eyre 2016)

You mentioned biriko. I asked Lassi Diabaté about that style. He played lovely example of it on guitar, but he couldn't really tell me much about it. You say it is half Fula and half Mande?

Biriko is a place. You get to Kita, which you can now get to on a beautiful tarmac road. It takes about two hours from Bamako. And then you turn south down from Kita, and you go on this very hilly, packed dirt road with lots of rocks in the middle, and then the road forks. The one on the left goes to Golobladji, and the one on the left goes down to Biriko. Biriko is an area like Wassoulou that was historically populated by Fula, Fulani, Fulbe. These were nomadic cattle herders, and over the centuries, they established themselves there. They became settled and Mande-ized. They lost their Fulani language, but they continue to maintain some musical traditions amongst themselves. It is very much like Wassoulou in that way.

There are no griots there. So the griots of the Fula are the Mande. But the Fula have these beautiful melodies that they sing, for example, when they are harvesting the land or weeding, or doing the sansene, this communal farming. They are really beautiful melodies. And you think, "Where do they get these melodies from?" They're just fabulous, and I think it comes from the confluence of these two cultures. On the one hand the Maninka—the French say Malinké—have been living there for centuries, since the time of Sunjata. And on the other hand, the Fula would've also been settled there for centuries. So the griots of one group are singing for the other, but also picking up their melodies and repertoire, and adapting their songs. And so it's just a very fertile region musically.

Toumani’s father, as I said, was born in the Gambia. But his grandfather also came from Biriko. They came from the small village called Galen, which is in Biriko. So there is something about that land, that region, which is just intensely and wonderfully musical.

Toumani, Sidiki, musicians and the First Lady of Mali, after the concert (Eyre 2016)

Toumani, Sidiki, musicians and the First Lady of Mali, after the concert (Eyre 2016)

To end, I want to touch on this whole question of religious life in Mali today. I did a long interview with the historian Gregory Mann at Columbia University. We spoke about these two religious leaders, Mahmoud Dicko and Cherif Ousmane Haïdara. Gregory was critical of Imam Dicko. He spoke about this family code law that Dicko played a big role in quashing in 2009.

Now when I interviewed the rapper Master Soumi, who seemed very grounded in clear-sighted, I was very surprised when he held up Dicko as an exemplar of "moderate" Islam. So recalling my conversation with Gregory, I asked him about the family code and, as we noted earlier, he backed away from criticizing Dicko. He said he needed to study it more. This was striking after he had been so bravely outspoken. He didn't hold back from criticizing the president, Ibrahim Boubacar Keita (IBK), but he held back here.

Yes, but the president is secular. He’s secular. The whole religious thing has become such a cat on a hot tin roof. It's a really tricky, dangerous area now with everything that has gone on in the north, and the rise of fundamentalism. Dicko is the head of the High Islamic Council of Mali. He has got an enormous amount of power. You know that he made this statement that the Radisson Hotel terrorist attack was something Mali brought upon itself, and it was justifiable because Mali tolerates homosexuality. Then the attorney general made a statement the next day and said that this was an outrageous thing to say. Whereupon IBK fires who? The attorney general.

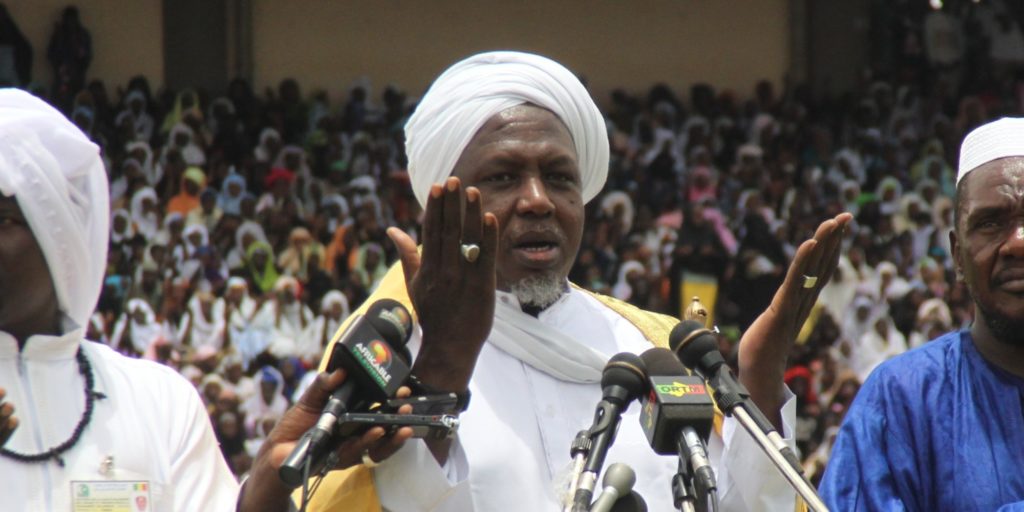

Mahmoud Dicko (center), head of Mali's High Islamic Council, prays on Aug. 12, 2012 in Bamako during a giant peace rally in Mali. Up to 60,000 people gathered in Bamako's main stadium. (Photo credit HABIBOU KOUYATE/AFP/GettyImages)

Mahmoud Dicko (center), head of Mali's High Islamic Council, prays on Aug. 12, 2012 in Bamako during a giant peace rally in Mali. Up to 60,000 people gathered in Bamako's main stadium. (Photo credit HABIBOU KOUYATE/AFP/GettyImages)

Gregory mentioned that.

So what kind of sign is that sending out? Basically, Dicko has a huge amount of power, and more and more, these kind of fundamentalist networks are gaining ground. Why? Because there is a complete power vacuum. Point number one. Number two, there is terrible endemic poverty with no hope of escaping that poverty. So the Wahhabis and other Islamic networks are infiltrating in Bamako big time, and offering money to recruit people. Wahhabis recruits, for instance, are offered a salary to join, and they are given little jobs. They become couriers. They become the people who sell telephone cards, and send money around via telephones in the city now, which has become a big business in the city.

So religion has become a sticky and dangerous aspect of life in southern Mali. That's my comment. It’s dangerous. So people are careful. Even the most outspoken rappers are hedging their bets. They are not going to critique Dicko.

What about Haïdara? I remember that Bassekou Kouyaté has been a big supporter of him.

Cherif Ousmane Madani Haïdara runs Ansar ud-Dine in the south. And he is really moderate. He preaches in Bamana, preaches about culture. He’s a bit like the Pope. He says we can interpret these things according to our cultural traditions. So he has a huge following, and he is constantly saying, "I am astonished when I wake up. I'm astonished that I am still alive.” Because he is just waiting to be bumped off at any moment. Because what he says is actually quite liberal. By the way, this business about him saying that he wakes up every morning is hearsay rather than anything that's been published. But it is something that everyone comments on.

But even he is still very much within a traditional, Islamic framework. And more and more, you see women wearing the hijab, and men wearing the three-quarter length Wahhabi trousers. I know jelis, griots, who have been in public transport in Mali talking to the person next to them, and when that person discovers they are a griot, they turn their back on them. They don't want to speak to them again, because there's such a disgust about music as a profession.

These things are complicated, and I think Mali is going into a very difficult phase, and I honestly don't know how it's going to come out, and I do seriously fear for its amazing musical traditions. What will happen if the south also falls under militant jihad rule? Those musicians will have to get out. And where are they going to go? Burkina? Burkina is not all that stable either. Are they going to go to Guinea? Guinea is not in any great state. And how are they going to maintain their traditions? I don't know. It is very worrying.

Wahhabi women in black at Bamako market (Eyre 2016)

It sure is. One last thing connecting these two themes, rappers and griots, and religious extremism. When I presented Toumani with the rapper's critique of griotism, and the idea that rappers are doing griot’s work, he went right past all that and immediately started talking about people who send their kids abroad to learn Wahhabi Islam. What you make of that?

It means that his son is a rapper and he is not going to hit on the rappers. He's not going to critique the rappers.

He actually praised the rappers. He just said they weren't doing the griot's work.

So he's going to deflect and talk about something else. Toumani is absolutely right that a lot of these Wahhabi ideas are coming in because young Malians are being offered scholarships to go study in Saudi Arabia and Qatar and places like that. So then they learn Arabic, and they come back, and their heads were full of all these ideas that are not cultural for Mali, which has always been liberal in its approach to Islam.

Let's face it. In most parts of Mali, Islam was only introduced about 100 years ago. The Bamana Empire—Segou only fell in 1861. And that was an animist empire, 150 years ago. So Islam has not been around for ages in most parts of Mali. In my 30 years of going there, I have seen an enormous change in terms of women wearing hijabs, women wearing black, changing attitudes towards music, and all this kind of thing. At the same time, Cherif Madani Haïdara fills stadiums every time he preaches, and also at the Maulid for the Prophet Mohammed, and guess who he has on either side of him when he does it? Zigiri men. So music has now become a really fundamental aspect of Islamic culture in southern Mali, I don't know how all this is going to pan out.

Fascinating, Lucy. We’ll all be watching. Thank you so much for all this.

My pleasure.

Niger River evening (Eyre 2016)