Blog October 31, 2016

On the Scene in Casablanca

Currently, cities throughout Morocco are filled with protesters. These are the largest and most widespread protests in Morocco since the February 20 movement, which coincided with the Arab Spring that spread throughout North African and the Middle East in 2011. The current protests were ignited by the death of a fishmonger named Mouhcine Fikri from the town of Al-Hoceima in the Rif region of northern Morocco, who was crushed to death by a garbage truck after police confiscated his fish. Protesters have taken to the streets to demand justice for Fikri’s death and call for an end to hogra, a term that refers to abuse and oppression by state officials. Afropop producer Jesse Brent spent the past summer in Morocco, where he met with musicians connected to Casablanca’s underground music scene, many of whom have taken active stances against the suffering that has sparked these protests. You can hear some of these artists in our new show “Moroccan Music Today: Re-Examined Past, Innovative Future.”

Casablanca is Morocco’s largest city, a place to which many Moroccans from other parts of the country have migrated for work. It is a bustling metropolis, full of construction and traffic. It’s also home to a thriving scene of underground musicians, drawing equally from Moroccan traditions like Issawa, chaabi and Gnawa, and international styles like rap, reggae and heavy metal. Sometimes known as Nayda, this movement has been fostered in part by the Boulevard des Jeunes Musiciens festival, which began in 1999, and has brought together rap, heavy metal and fusion artists ever since. Unfortunately, this year’s edition of the Boulevard festival was recently canceled due to a lack of funds. Nevertheless, today in Casablanca, it is fashionable to sing and rap in Darija, Moroccan Arabic, the language of the streets. That wasn’t always the case. Even Nass El Ghiwane, the most popular and iconic Moroccan band of the ‘70s and ‘80s, sang in Arabic that had a classical tinge to it.

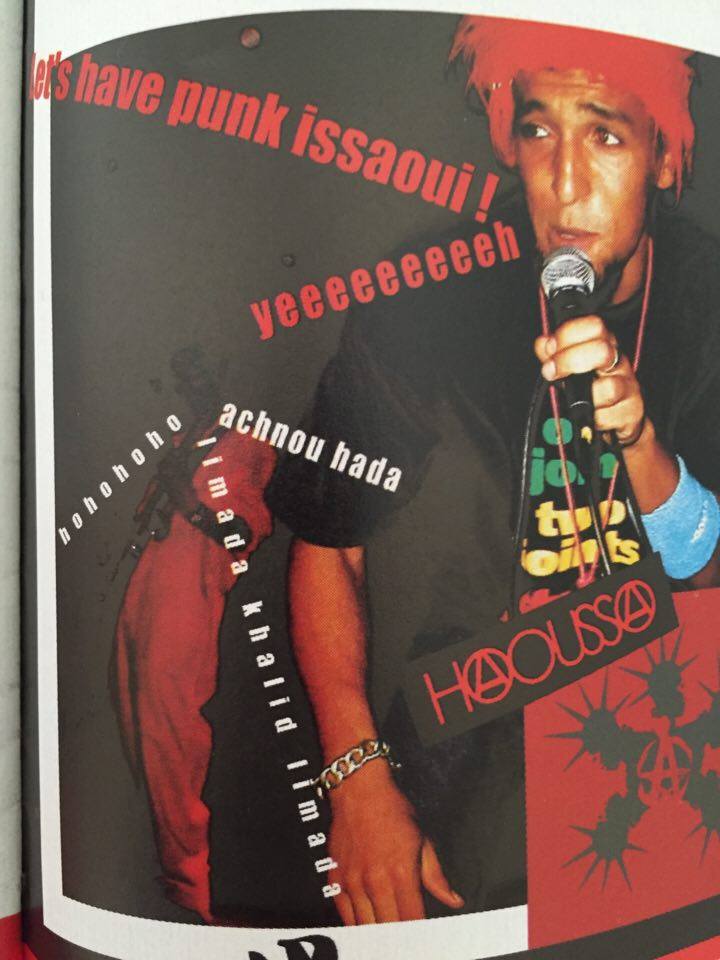

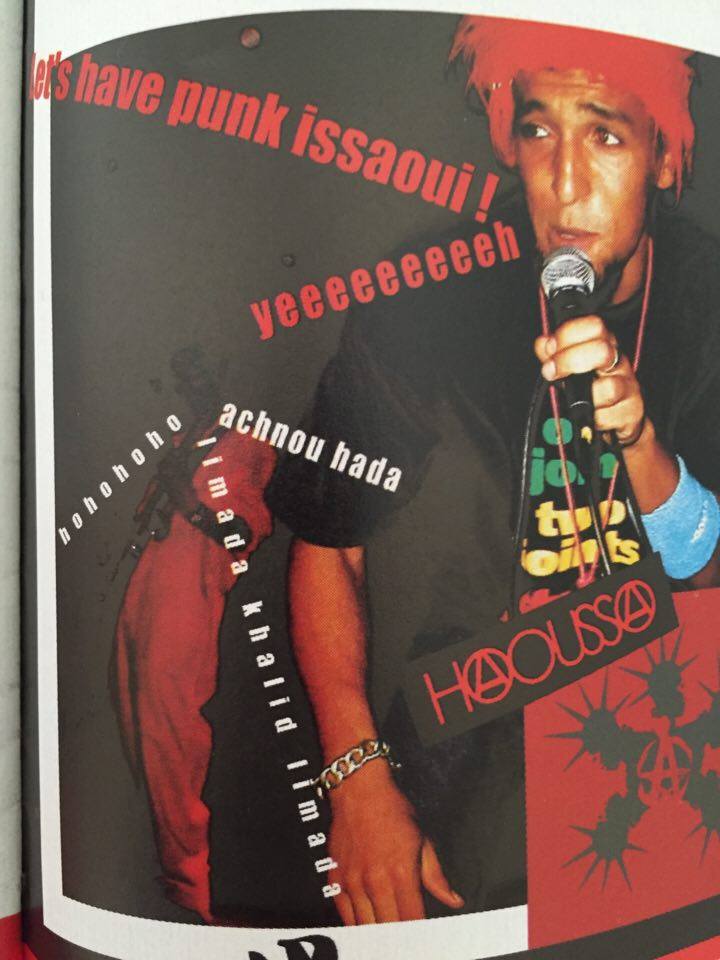

[caption id="attachment_32487" align="alignnone" width="450"] Photo taken from the Kounache du Boulevard des Jeunes Musiciens magazine[/caption]

Fadoul, a Moroccan singer from that same era, can be considered a precursor to the current underground scene in Casablanca. Influenced by funk and reggae, he sang with the raw energy of James Brown and toasted in Darija over King Tubby dubs. Recently, Habibi Funk has reissued some of his terrific recordings from this period.

Though not Moroccan themselves, an important influence on the Casablanca underground scene is Gnawa Diffusion, a band led by Amazigh Kateb, who drew from Gnawa, music of former slaves in Morocco, as well as the politically engaged lyrics of Bob Marley, connecting them through shared Africanité. Gnawa Diffusion became a sort of “gateway drug” for traditional Moroccan music, leading to renewed interest in styles like Gnawa among young Moroccans raised on MTV.

Hip-hop, which started as early as the ‘80s in Morocco, became widely popular in the mid ‘90s. Many of the early Moroccan rappers took explicitly political stances, rapping about social issues as the country pursued a neoliberal economic policy that reduced welfare and created an increasing economic inequality. Double A, a duo, consisting of Aminoffice and Ahmad, is often credited as the first Moroccan rap group to put out a CD in 1996.

Another pioneer of both hip-hop and fusion in Morocco is Barry, a rapper and singer, who was influenced by Gnawa Diffusion and associated with both the rap and rock scenes of Casablanca. On his 2009 album Siba Barry explicitly refers to a movement, bringing together rap, rock and fusion artists, and criticizes the police.

Soultana, one of the first female MCs in Morocco, started as a B-girl in Casablanca. Influenced by Tupac, she formed a group of female rappers called Tigress Flow, and won the Mawazine hip-hop competition in 2008. More recently, she has recorded a track called “Jokko #3” with two other female rappers from other parts of Africa--Eben from Mauritania and Fatim from Senegal. I visited Soultana in Meknes, where we spoke at a coffee shop about her experience witnessing the Arab Spring in Egypt and her own rapping, which concentrates on issues facing women and social injustices in Morocco.

One major event that brought attention to the Casablanca underground was the Satanic Affair of 2003, in which 14 heavy metal musicians were condemned to up to a year in prison for “crimes against the Muslim faith” and supposed membership in a Satanic cult. Among those musicians was Amine Hamma, who I met at the new state-of-the-art Studio Hiba in Casablanca. Amine is currently a guitarist in the bands Haoussa and Betweenatna, whose song “3abada” (literally “worshippers,” as the musicians were called in prison) tells the story of the affair. Betweenatna brings together musicians from some of Casablanca’s most influential groups--Haoussa, Hoba Hoba Spirit and Darga. Haoussa combines the Issawa Sufi tradition with a highly charged punk rock attitude. Haoussa’s lyrics often refer to government corruption and problems of Moroccan society.

I visited dub producer Saj Moor at his West Coast Studios in Casablanca. Saj spent years in California, where he studied music production and played in reggae groups, before returning to Morocco. He told me that growing up in Aïn Sebaâ, a suburb of Casablanca, he was surrounded by reggae from a young age. This summer, Saj organized a concert by African Roots, a Moroccan reggae band, formed in the '80s in Aïn Sebaâ at the Boultek, one of Casablanca's most important music venues. Saj also works with Bob Maghrib, a group that plays Bob Marley songs with Moroccan traditional instruments, along with other well-known members of the Casablanca scene like Barry.

[caption id="attachment_32486" align="alignnone" width="600"]

Photo taken from the Kounache du Boulevard des Jeunes Musiciens magazine[/caption]

Fadoul, a Moroccan singer from that same era, can be considered a precursor to the current underground scene in Casablanca. Influenced by funk and reggae, he sang with the raw energy of James Brown and toasted in Darija over King Tubby dubs. Recently, Habibi Funk has reissued some of his terrific recordings from this period.

Though not Moroccan themselves, an important influence on the Casablanca underground scene is Gnawa Diffusion, a band led by Amazigh Kateb, who drew from Gnawa, music of former slaves in Morocco, as well as the politically engaged lyrics of Bob Marley, connecting them through shared Africanité. Gnawa Diffusion became a sort of “gateway drug” for traditional Moroccan music, leading to renewed interest in styles like Gnawa among young Moroccans raised on MTV.

Hip-hop, which started as early as the ‘80s in Morocco, became widely popular in the mid ‘90s. Many of the early Moroccan rappers took explicitly political stances, rapping about social issues as the country pursued a neoliberal economic policy that reduced welfare and created an increasing economic inequality. Double A, a duo, consisting of Aminoffice and Ahmad, is often credited as the first Moroccan rap group to put out a CD in 1996.

Another pioneer of both hip-hop and fusion in Morocco is Barry, a rapper and singer, who was influenced by Gnawa Diffusion and associated with both the rap and rock scenes of Casablanca. On his 2009 album Siba Barry explicitly refers to a movement, bringing together rap, rock and fusion artists, and criticizes the police.

Soultana, one of the first female MCs in Morocco, started as a B-girl in Casablanca. Influenced by Tupac, she formed a group of female rappers called Tigress Flow, and won the Mawazine hip-hop competition in 2008. More recently, she has recorded a track called “Jokko #3” with two other female rappers from other parts of Africa--Eben from Mauritania and Fatim from Senegal. I visited Soultana in Meknes, where we spoke at a coffee shop about her experience witnessing the Arab Spring in Egypt and her own rapping, which concentrates on issues facing women and social injustices in Morocco.

One major event that brought attention to the Casablanca underground was the Satanic Affair of 2003, in which 14 heavy metal musicians were condemned to up to a year in prison for “crimes against the Muslim faith” and supposed membership in a Satanic cult. Among those musicians was Amine Hamma, who I met at the new state-of-the-art Studio Hiba in Casablanca. Amine is currently a guitarist in the bands Haoussa and Betweenatna, whose song “3abada” (literally “worshippers,” as the musicians were called in prison) tells the story of the affair. Betweenatna brings together musicians from some of Casablanca’s most influential groups--Haoussa, Hoba Hoba Spirit and Darga. Haoussa combines the Issawa Sufi tradition with a highly charged punk rock attitude. Haoussa’s lyrics often refer to government corruption and problems of Moroccan society.

I visited dub producer Saj Moor at his West Coast Studios in Casablanca. Saj spent years in California, where he studied music production and played in reggae groups, before returning to Morocco. He told me that growing up in Aïn Sebaâ, a suburb of Casablanca, he was surrounded by reggae from a young age. This summer, Saj organized a concert by African Roots, a Moroccan reggae band, formed in the '80s in Aïn Sebaâ at the Boultek, one of Casablanca's most important music venues. Saj also works with Bob Maghrib, a group that plays Bob Marley songs with Moroccan traditional instruments, along with other well-known members of the Casablanca scene like Barry.

[caption id="attachment_32486" align="alignnone" width="600"] African Roots at the Boultek in Casablanca (Photo by Jesse Brent)[/caption]

Khalil Mounji is the founder of Gnaoua Culture, an organization based in Casablanca that helps Gnawa musicians by making music videos and handling their publicity. They also released an app that can teach you how to play the guembri on your smartphone. Mounji is dedicated to preserving Gnawa’s cultural and historical knowledge, and also promoting some young and talented Gnawa musicians like Asmâa Hamzaoui. Asmâa, who is just 19 years old, is both one of the youngest Gnawa musicians to make a name for herself in Morocco and one of the only female Gnawa musicians to play publicly. She performs with a group of female friends called the Bnat Timbouktou. I met with Asmâa in her family’s apartment in Casablanca. She is the daughter of a mâalem (master), who taught her both how to play the guembri and brought her to lilas, ceremonies where Gnawa musicians perform healing rituals through trance. Asmâa is now creating her own fusion music, mixing Gnawa with influences from Malian music.

[caption id="attachment_32488" align="alignnone" width="450"]

African Roots at the Boultek in Casablanca (Photo by Jesse Brent)[/caption]

Khalil Mounji is the founder of Gnaoua Culture, an organization based in Casablanca that helps Gnawa musicians by making music videos and handling their publicity. They also released an app that can teach you how to play the guembri on your smartphone. Mounji is dedicated to preserving Gnawa’s cultural and historical knowledge, and also promoting some young and talented Gnawa musicians like Asmâa Hamzaoui. Asmâa, who is just 19 years old, is both one of the youngest Gnawa musicians to make a name for herself in Morocco and one of the only female Gnawa musicians to play publicly. She performs with a group of female friends called the Bnat Timbouktou. I met with Asmâa in her family’s apartment in Casablanca. She is the daughter of a mâalem (master), who taught her both how to play the guembri and brought her to lilas, ceremonies where Gnawa musicians perform healing rituals through trance. Asmâa is now creating her own fusion music, mixing Gnawa with influences from Malian music.

[caption id="attachment_32488" align="alignnone" width="450"] Asmâa Hamzaoui, performing at her home in Casablanca (Photo by Jesse Brent)[/caption]

Another fusion group in Casablanca, Made in Bled is also highly influenced by Gnawa Diffusion. Combining reggae and funk with Gnawa, chaabi, and malhun, the band’s singer Salim Salah writes lyrics that explore taboo subjects like prostitution and inequality. He told me that for that reason, Made in Bled don’t get played on the radio in Morocco. Nevertheless, Made in Bled has won several prizes for their live performances and are working on releasing their first album.

Asmâa Hamzaoui, performing at her home in Casablanca (Photo by Jesse Brent)[/caption]

Another fusion group in Casablanca, Made in Bled is also highly influenced by Gnawa Diffusion. Combining reggae and funk with Gnawa, chaabi, and malhun, the band’s singer Salim Salah writes lyrics that explore taboo subjects like prostitution and inequality. He told me that for that reason, Made in Bled don’t get played on the radio in Morocco. Nevertheless, Made in Bled has won several prizes for their live performances and are working on releasing their first album.

Photo taken from the Kounache du Boulevard des Jeunes Musiciens magazine[/caption]

Fadoul, a Moroccan singer from that same era, can be considered a precursor to the current underground scene in Casablanca. Influenced by funk and reggae, he sang with the raw energy of James Brown and toasted in Darija over King Tubby dubs. Recently, Habibi Funk has reissued some of his terrific recordings from this period.

Though not Moroccan themselves, an important influence on the Casablanca underground scene is Gnawa Diffusion, a band led by Amazigh Kateb, who drew from Gnawa, music of former slaves in Morocco, as well as the politically engaged lyrics of Bob Marley, connecting them through shared Africanité. Gnawa Diffusion became a sort of “gateway drug” for traditional Moroccan music, leading to renewed interest in styles like Gnawa among young Moroccans raised on MTV.

Hip-hop, which started as early as the ‘80s in Morocco, became widely popular in the mid ‘90s. Many of the early Moroccan rappers took explicitly political stances, rapping about social issues as the country pursued a neoliberal economic policy that reduced welfare and created an increasing economic inequality. Double A, a duo, consisting of Aminoffice and Ahmad, is often credited as the first Moroccan rap group to put out a CD in 1996.

Another pioneer of both hip-hop and fusion in Morocco is Barry, a rapper and singer, who was influenced by Gnawa Diffusion and associated with both the rap and rock scenes of Casablanca. On his 2009 album Siba Barry explicitly refers to a movement, bringing together rap, rock and fusion artists, and criticizes the police.

Soultana, one of the first female MCs in Morocco, started as a B-girl in Casablanca. Influenced by Tupac, she formed a group of female rappers called Tigress Flow, and won the Mawazine hip-hop competition in 2008. More recently, she has recorded a track called “Jokko #3” with two other female rappers from other parts of Africa--Eben from Mauritania and Fatim from Senegal. I visited Soultana in Meknes, where we spoke at a coffee shop about her experience witnessing the Arab Spring in Egypt and her own rapping, which concentrates on issues facing women and social injustices in Morocco.

One major event that brought attention to the Casablanca underground was the Satanic Affair of 2003, in which 14 heavy metal musicians were condemned to up to a year in prison for “crimes against the Muslim faith” and supposed membership in a Satanic cult. Among those musicians was Amine Hamma, who I met at the new state-of-the-art Studio Hiba in Casablanca. Amine is currently a guitarist in the bands Haoussa and Betweenatna, whose song “3abada” (literally “worshippers,” as the musicians were called in prison) tells the story of the affair. Betweenatna brings together musicians from some of Casablanca’s most influential groups--Haoussa, Hoba Hoba Spirit and Darga. Haoussa combines the Issawa Sufi tradition with a highly charged punk rock attitude. Haoussa’s lyrics often refer to government corruption and problems of Moroccan society.

I visited dub producer Saj Moor at his West Coast Studios in Casablanca. Saj spent years in California, where he studied music production and played in reggae groups, before returning to Morocco. He told me that growing up in Aïn Sebaâ, a suburb of Casablanca, he was surrounded by reggae from a young age. This summer, Saj organized a concert by African Roots, a Moroccan reggae band, formed in the '80s in Aïn Sebaâ at the Boultek, one of Casablanca's most important music venues. Saj also works with Bob Maghrib, a group that plays Bob Marley songs with Moroccan traditional instruments, along with other well-known members of the Casablanca scene like Barry.

[caption id="attachment_32486" align="alignnone" width="600"]

Photo taken from the Kounache du Boulevard des Jeunes Musiciens magazine[/caption]

Fadoul, a Moroccan singer from that same era, can be considered a precursor to the current underground scene in Casablanca. Influenced by funk and reggae, he sang with the raw energy of James Brown and toasted in Darija over King Tubby dubs. Recently, Habibi Funk has reissued some of his terrific recordings from this period.

Though not Moroccan themselves, an important influence on the Casablanca underground scene is Gnawa Diffusion, a band led by Amazigh Kateb, who drew from Gnawa, music of former slaves in Morocco, as well as the politically engaged lyrics of Bob Marley, connecting them through shared Africanité. Gnawa Diffusion became a sort of “gateway drug” for traditional Moroccan music, leading to renewed interest in styles like Gnawa among young Moroccans raised on MTV.

Hip-hop, which started as early as the ‘80s in Morocco, became widely popular in the mid ‘90s. Many of the early Moroccan rappers took explicitly political stances, rapping about social issues as the country pursued a neoliberal economic policy that reduced welfare and created an increasing economic inequality. Double A, a duo, consisting of Aminoffice and Ahmad, is often credited as the first Moroccan rap group to put out a CD in 1996.

Another pioneer of both hip-hop and fusion in Morocco is Barry, a rapper and singer, who was influenced by Gnawa Diffusion and associated with both the rap and rock scenes of Casablanca. On his 2009 album Siba Barry explicitly refers to a movement, bringing together rap, rock and fusion artists, and criticizes the police.

Soultana, one of the first female MCs in Morocco, started as a B-girl in Casablanca. Influenced by Tupac, she formed a group of female rappers called Tigress Flow, and won the Mawazine hip-hop competition in 2008. More recently, she has recorded a track called “Jokko #3” with two other female rappers from other parts of Africa--Eben from Mauritania and Fatim from Senegal. I visited Soultana in Meknes, where we spoke at a coffee shop about her experience witnessing the Arab Spring in Egypt and her own rapping, which concentrates on issues facing women and social injustices in Morocco.

One major event that brought attention to the Casablanca underground was the Satanic Affair of 2003, in which 14 heavy metal musicians were condemned to up to a year in prison for “crimes against the Muslim faith” and supposed membership in a Satanic cult. Among those musicians was Amine Hamma, who I met at the new state-of-the-art Studio Hiba in Casablanca. Amine is currently a guitarist in the bands Haoussa and Betweenatna, whose song “3abada” (literally “worshippers,” as the musicians were called in prison) tells the story of the affair. Betweenatna brings together musicians from some of Casablanca’s most influential groups--Haoussa, Hoba Hoba Spirit and Darga. Haoussa combines the Issawa Sufi tradition with a highly charged punk rock attitude. Haoussa’s lyrics often refer to government corruption and problems of Moroccan society.

I visited dub producer Saj Moor at his West Coast Studios in Casablanca. Saj spent years in California, where he studied music production and played in reggae groups, before returning to Morocco. He told me that growing up in Aïn Sebaâ, a suburb of Casablanca, he was surrounded by reggae from a young age. This summer, Saj organized a concert by African Roots, a Moroccan reggae band, formed in the '80s in Aïn Sebaâ at the Boultek, one of Casablanca's most important music venues. Saj also works with Bob Maghrib, a group that plays Bob Marley songs with Moroccan traditional instruments, along with other well-known members of the Casablanca scene like Barry.

[caption id="attachment_32486" align="alignnone" width="600"] African Roots at the Boultek in Casablanca (Photo by Jesse Brent)[/caption]

Khalil Mounji is the founder of Gnaoua Culture, an organization based in Casablanca that helps Gnawa musicians by making music videos and handling their publicity. They also released an app that can teach you how to play the guembri on your smartphone. Mounji is dedicated to preserving Gnawa’s cultural and historical knowledge, and also promoting some young and talented Gnawa musicians like Asmâa Hamzaoui. Asmâa, who is just 19 years old, is both one of the youngest Gnawa musicians to make a name for herself in Morocco and one of the only female Gnawa musicians to play publicly. She performs with a group of female friends called the Bnat Timbouktou. I met with Asmâa in her family’s apartment in Casablanca. She is the daughter of a mâalem (master), who taught her both how to play the guembri and brought her to lilas, ceremonies where Gnawa musicians perform healing rituals through trance. Asmâa is now creating her own fusion music, mixing Gnawa with influences from Malian music.

[caption id="attachment_32488" align="alignnone" width="450"]

African Roots at the Boultek in Casablanca (Photo by Jesse Brent)[/caption]

Khalil Mounji is the founder of Gnaoua Culture, an organization based in Casablanca that helps Gnawa musicians by making music videos and handling their publicity. They also released an app that can teach you how to play the guembri on your smartphone. Mounji is dedicated to preserving Gnawa’s cultural and historical knowledge, and also promoting some young and talented Gnawa musicians like Asmâa Hamzaoui. Asmâa, who is just 19 years old, is both one of the youngest Gnawa musicians to make a name for herself in Morocco and one of the only female Gnawa musicians to play publicly. She performs with a group of female friends called the Bnat Timbouktou. I met with Asmâa in her family’s apartment in Casablanca. She is the daughter of a mâalem (master), who taught her both how to play the guembri and brought her to lilas, ceremonies where Gnawa musicians perform healing rituals through trance. Asmâa is now creating her own fusion music, mixing Gnawa with influences from Malian music.

[caption id="attachment_32488" align="alignnone" width="450"] Asmâa Hamzaoui, performing at her home in Casablanca (Photo by Jesse Brent)[/caption]

Another fusion group in Casablanca, Made in Bled is also highly influenced by Gnawa Diffusion. Combining reggae and funk with Gnawa, chaabi, and malhun, the band’s singer Salim Salah writes lyrics that explore taboo subjects like prostitution and inequality. He told me that for that reason, Made in Bled don’t get played on the radio in Morocco. Nevertheless, Made in Bled has won several prizes for their live performances and are working on releasing their first album.

Asmâa Hamzaoui, performing at her home in Casablanca (Photo by Jesse Brent)[/caption]

Another fusion group in Casablanca, Made in Bled is also highly influenced by Gnawa Diffusion. Combining reggae and funk with Gnawa, chaabi, and malhun, the band’s singer Salim Salah writes lyrics that explore taboo subjects like prostitution and inequality. He told me that for that reason, Made in Bled don’t get played on the radio in Morocco. Nevertheless, Made in Bled has won several prizes for their live performances and are working on releasing their first album.