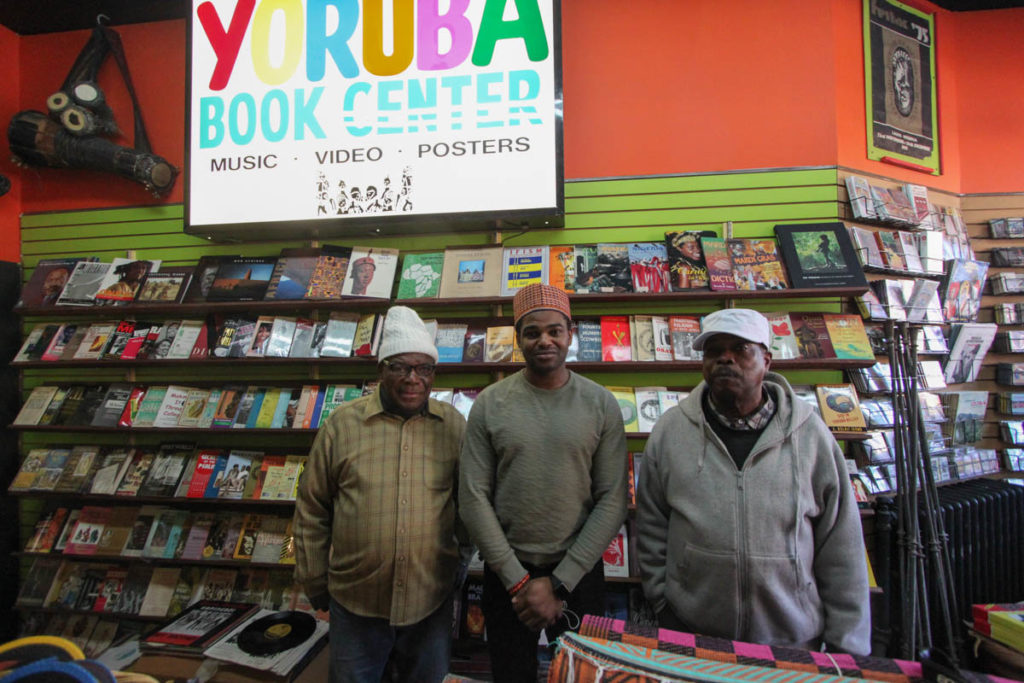

Brooklyn, New York is a melting pot of many nationalities and cultures. There are also seemingly a million places that exhibit and pay homage to the history of these cultures. Tucked away in the heart of Prospect Lefferts Garden are many Caribbean and African shops selling a variety of things, but one place that really stands out is the African Record Center on Nostrand Ave. run by the Francis brothers. On Feb. 6, Nenim Iwebuke met with Roger and Rudolph Francis to discuss the rich history of the institution.

Nenim Iwebuke: I see you guys have got a beautiful place here, lovely books and records. Can you let us know a little about yourselves?

Roger Francis: Certainly, we are the African Record Center. We started approximately in 1969, distributing African music, promoting African music and introducing African music. Our first effort was to introduce African music into the United States because before that time nothing existed. There was no African music to speak of and if there were, there’ll be one or two incidental albums or something like that. Our goal, however, was to stock the largest selection of African music, representative of the entire continent of Africa. That took us all over the world, in doing so, to reach the pinnacle of what we wanted to do. By 1970, we were in Nigeria and our junior brother, Roland Francis, spent a year in Nigeria, that was during the Biafran war where he met and spoke to all of the major Nigerian musicians such as Rex Lawson, Fela Kuti, Ebenezer Obey, Dele Ojo, just to name a few out of the many. That resulted in us importing a very large amount of Nigerian music. Prior to that we had been in Europe where we were able to find some titles, not many but some, and as a result we arrived as the African Records Center distributors. Now, not only did we import African music, we began to distribute African music by 1974. We had a major hit in 1972, which was Manu Dibango’s “Soul Makossa,” and the thing about that particular incident that made it phenomenal was that no radio station wanted to play African music. They claimed there was a language barrier, they claimed that the tracks were too long, they weren’t commercial, and they claimed that their listeners would not like the African music or appreciate it.

However, in 1972 we had the underground hit, “Soul Makossa” and that was an underground hit in terms of it had been started in basement parties, house parties, and it became so popular that it spilled out into the public—the mass public, and then radios were kind of forced to play it [Laughs] because there was such a demand to hear it. That record launched Manu Dibango’s career in 1972. By 1973, we introduced the Lafayette Afro Rock Band, which was an international group, comprised of international musicians. That also became very popular and that was a big hit in 1973 and at that time radio stations were very happy to play African music. By 1974, we received a call from Fela Kuti from Nigeria, and Fela insisted that we put out his records out here in the United States and distribute them; within a week’s time we had master recordings from Fela, and we released about eight of his albums between 1974 and maybe 1976 or ‘78. The biggest hit of which was “Shakara Oloje” and “Lady,” and that record actually launched Fela to international reputation all over the world, you know, like they say, “If it’s big in America then it’s big everywhere else.” So that brings us to about 1974, the rest after that is history. We began to distribute African music all over the world, we were in contact with many people but one of the crowning achievements that we feel that we’ve accomplished apart from that is that when we started out in 1969, as I said, there was no African music and one of the things we found was that even in Africa, much of African music had not crossed its borders. In other words, if you were in Nigeria, very rarely did you hear or listen to the music from Zaire or Cameroon. While all of this was happening, however, we can understand the course of that through the advent of colonialism and Africa being divided into separate states and countries.

During that time, however, we opened the African Record Center in New York City; our first store was based in Harlem, in Manhattan and one of our crowning achievements was that we would bring African nationals together from all over the continent, whether they were dignitaries from United Nations or African students, it was the place where African nationals met in New York City. They could hear and be exposed to various forms of African music and so that made us very international in that sense. We feel that we brought the African community together as a homogeneous community, and as a result of that, the music kind of took on a greater dynamics. People from, for instance: Sierra Leone loved the Zairian music, Nigerians liked other kinds of music and all of this was possible to come together at the African Record Center doors. We spent a great deal of time explaining to people that apart from just being what they coined the phrase, “a shop,” that we are an institution. We have always regarded ourselves as an institution, an institution to further African music and promote it in the United States and all over the world. So that’s like an early beginning of how we started, where we started, and why we started and so forth.

I see one of you is with Manu Dibango in the photo.

Yes, that’s our brother, Roland, who traveled to Paris during the hit “Soul Makossa” and he met with Manu Dibango. He more or less broadened Manu Dibango’s insight into what African music was like in the United States, maybe to an extent how it could be a crossover to different countries and different cultures, so it was a very fruitful conversation as at that time. Roland was our spearhead so to speak, he was in Nigeria, he was in Paris, and he was in Italy, name it and he was there.

How was working with Manu Dibango?

It was very interesting, when the song; “Soul Makossa” was originally recorded; the other side was for the eight World Cup soccer match in Cameroon. Manu originally recorded the song because of the football match, the other side was “Soul Makossa,” however our ear was tuned to something else and so we found “Soul Makossa” to be the very dynamic product that it was, very danceable. We have to remember also that was the beginning of the disco era, so it was the perfect record to jump into the disco, it even lead it to some extent. By then disco was really appreciated in house parties, of course there were clubs like Studio 54 that got to be known for disco but the disco was really in the house parties. It was at a very popular level at basement parties and this was where “Soul Makossa” kind of brought the disco out from underground to above ground. You could walk down the streets and hear “Soul Makossa” coming out of buildings and apartments, that’s how often it was played.

And how was it working with Fela?

Fela was very interesting. Our brother that we mentioned [Roland] and Rudy actually went to Nigeria, stayed with Fela, and got him in tune with what the scene was in the United States, although he had been here previously, probably by 1969 I believe, but that was a short trip for him and that was when he was playing with Koola Lobitos, so that was more jazz oriented. So we found Fela to be very interesting, it was quite a dynamic development I mean in terms of Afrobeat and the genesis of it, but it was a rhythm that immediately caught on in the United States.

Photos by Sebastian Bouknight

Photos by Sebastian Bouknight

Many of his songs were played on radio and it became very popular. The music itself at its base had James Brown flavor so it was very easy to crossover and it became very dynamic in that sense. Working with Fela himself, very interesting person. [Laughs] We have his posters, where he was running for “Black President,” we also have his other posters, a very dynamic character who was needed, and when I use the word “character,” I mean by personality. Definitely a spokesman on behalf of Africa, which was really necessary because as Fela says, “the music is the weapon,” you know. This was important at that time in Nigeria and in several other African countries; we found the same thing to be true with Franco in OK Jazz. The thing about African music is that, it takes on various proportions; it is a popular music but it is also a music of message and so whether they sing about love or political concepts, needs and developments, it’s equally important and this is the music that Africa has produced. It’s primarily utilitarian, it’s not like the music in the Western countries where it’s “love me baby, love me baby and love me baby!” It takes on a different proportion and so it is very popular in that sense and this is what we found as a thread that ran through African music at that time. We have to remember that during that time as they had said, it was the year of African independence. During that period of time when African countries were becoming independent one after the other by 1960, ‘61, and ’69 so it was quite a dynamic period for the music and the musicians.

That’s quite some good history sir.

Thank you.

So if I may ask, what got you guys interested in African music? Because I know you guys are American.

For the most part. [Laughs]

But we all go back to Africa, what caught you guys’ interest?

Well, that’s an interesting question, Nenim, and probably the best one yet. What caught our interest is like I said, earlier in the United States there was no African music and there was a little sense of things African. In other words, it was relegated to Africa, outside of the United States. Growing up as young people attending high school, we found that there was nothing being taught about African culture or black culture. In particular the school I went to and the school Roland went to, I think it’s symbolic of most of the high schools in the United States and so we wanted to do something that would introduce and represent our desire, feelings and interest in Africa and its music. We formed a folkloric ensemble by 1963 and we actually performed and toured in the United States; introducing African traditional dances, cultures, songs, throughout the United States. As a result of that, it grew and grew and grew and the interest developed and developed.

So if I can just jump ahead now, regarding the music after the development of African Record Center distributors of the music, we found there was also a necessity to introduce books dealing with African spirituality because again there’s was no concept of African spirituality. So we focused on the Yoruba spirituality of Nigeria because this spirituality was developed and maintained in Cuba, Brazil and in Haiti, so it’s very close. It’s nothing foreign, there are many people in the United States now who adhere to the Yoruba religion, so we were the first to put out books on the Yoruba religion; we published about 50, close to 60 books by the leading scholars of Yoruba religion in Nigeria. A lot of this information had not been recorded as through oral tradition and through the tradition of the babalawo; in the tradition of the Yoruba society it is committed to memory. So we were the first to introduce those elements into book form and we are very proud of that and this was around 1990, 1986. So our whole quest has been: to introduce, maintain and develop things African, in terms of its music and culture, and the interest started when we were young, well, we are still young. [Laughs] Well, the thing that I really want to stress again is that sometimes people walk into our establishment, they look around, they say that it’s nice and of course we appreciate that. We, however, look at ourselves as an institution, as a worldwide institution. You will, for instance, see on our sign “world famous African Record Center” and we are an institution in the United States that has maintained and developed African music and spirituality.

That’s good, speaking of spirituality, now linking your books. Many people even back home in Africa, don’t even like to think about spirituality like juju and in Haiti or in the Caribbean where they have vodou, so many people feel this is evil except those that are well read know that that’s not true. What do you feel about this?

Well, through research study and active participation we have found that of course it’s a misnomer, it’s a stereotype; the African religion, and I’m speaking now about Yoruba religion is a religion that, well I don’t want to say that it predates other religions because that tends to cause controversy. It is the oldest religion though because it has to do with nature, all of the African, the Yoruba divinity, the orishas have to do with nature so it is a religion that has come from the creation of the world to the present. As far as vodou goes, I should mention immediately that in the Republic of Benin the vodou religion has now been sanctioned by the government, in other words, they now protect this religion. They promote this religion as being a bona fide religion and as an indigenous religion. This is one of the things that we have to ask ourselves continuously if we want to be honest and find the answer; “Does Africa not have its own religion?” We know about Christianity, we know about Islam, but these were religions that were imported or brought to Africa, so we have to ask about the indigenous religions; what religions and spirituality have the people depended on for ages and ages? Vodou in terms of Haiti has gotten a bad name but when the slaves were brought or Africans were brought from Africa they brought their religions and their religious beliefs among other things; which were so strong that they were able to develop them in the Western Hemisphere. So today you have in Cuba the lucumi or Yoruba, you have in Brazil—the candomble, you have in Haiti,—vodou and they may be slightly different systems of religion, they all are indigenous based religions of Africa.

In other words, that is to say wherever our people have gone and they have carried their religion with them. We could probably extrapolate further about the Christian religion in the Deep South because there are strains of the African religion there as well, whether one can recognize it or admit it still exists. The gospel, the meaning of gospel songs so it’s a culture and African culture has its own spirituality; I might add that in 2017 the Yoruba religion is now expanding and expanding outside of Nigeria, not only to Nigerians, or African-Americans but also too many Europeans as well. We have seen over the years because again we are the primary source of books, religious objects dealing with Yoruba religion. We’ve seen all kinds of people are now attracted to the Yoruba religion, so it is alive, it is well, it is growing and possibly one the most important elements that is needed is to be taken back to Africa, it needs to be demonstrated that the religion is alive and well in the United States and it needs to be strengthened more in Nigeria in its natural form. So you have a lot of people having a lot of adherents from Cuba, who are going to Nigeria, and they are taking a different view of their own lucumi indigenous Cuban religion; they are going to Nigeria now to get deeper and deeper and deeper, same with Brazil. Not too long ago we were in Republic of Benin and the Brazilian influence is very strong there in terms of Brazilians coming to the Republic of Benin from which they were taken as slaves, taken and made slaves to be brought to Brazil. So we have this rebirth of the religion that’s happening all over the black world, all over the African world and it’s also spreading out of Nigeria now because the religion is in Benin, it’s in Togo as well, in different forms.

That’s cool! I see you also have African attires, the jewelry, and a lot of antiques. How do you get these? They don’t look like they are made here.

That’s very true. These are through our contacts, we import from various African countries. I might add also at the inception of our development, we attended the High School of Fashion Industries, and so we had a very close connection to fashion. So we also did introduce at the late 1960s African fashion, where we brought in African fabrics of different kinds; we designed and created garments and sold them in the commercial markets, I should say, distribute through fashion shows. Many of the most important department stores bought our designs and clothing and so forth.

What fashion school are you talking about?

The High School of Fashion Industries based in Manhattan.

Going back, you said something like you guys performed as well, so are you musicians?

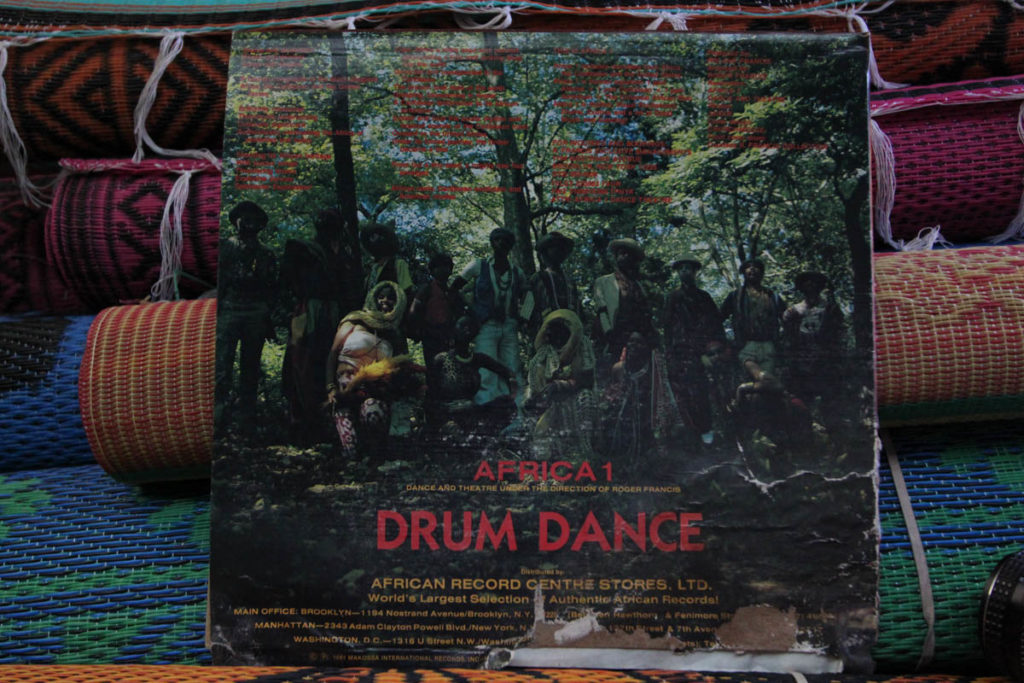

Yes, we are. We had the group, “The Egbe Omo Anago,” which was comprised of about 20 to 30 members: dancers, singers, musicians; this is one of our recordings. [Shows Nenim a record]

I bought this record a few days ago.

Yes, how did you like it?

I loved it, great record.

We recorded about three albums over that period of time and we were one of the leading groups; we performed at the New York World’s Fair in 1965, we performed at the World’s Fair, Knoxville, Tennessee, we performed at universities and high schools through out the United States and it was a very exciting time. All of this coincided with that period in the United States of resurgence and awareness for black people, so it was a very exciting time and I think everyone attempted to do and make a contribution in the way that they could. Our contribution was the introduction of African music and the introduction of the African spirituality. These are enduring factors with enduring values and we are very proud of that work we did then and continue to do.

With Black History month coming up, what do you guys have planned out?

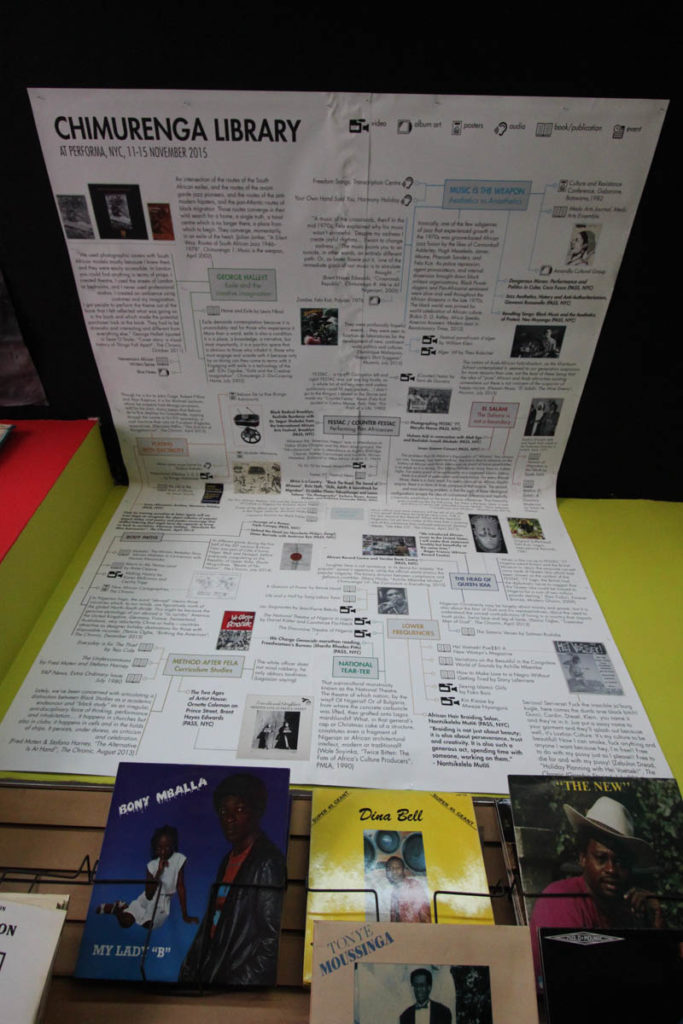

Well basically, what happens is we will be contacted by various institutions who would ask us to do installations of some kind or exhibitions or something of that nature where we can we always be willing to comply with that. One of the things we recently did was the Chimurenga Library, which was part of a performer program, they asked us to do an installation of the African Record Center at their particular event.

We actually moved the contents of the store from its location to their location in Manhattan; it was a big event that took place for a week and so we replicated the store, its design and everything in it, it was very interesting. There were people from all over the world. So those are the kind of events that we look forward to doing. Also, we’ve done many projects in Africa as well. We look forward to working with Africa any time that we can on a cultural level, whether it be music, whether it be spirituality we are always very open to that, to have partnerships to work on projects and programs.

That’s cool. I’m impressed sir. We know New York is a very expensive place and the price of property keeps on going up. How have you guys been able to still keep this gem of a place when many places fold up, what’s the secret?

Well, the secret is we have done a good job in managing the affairs, as I said, we have an international outreached. Probably more important than anything else that we’re grateful for is that we do have many loyal customers and very loyal partners in our endeavors. We’ve been able to maintain ourselves in a very good, positive and structured way and that’s why I use the word institution because we are an institution and we are recognized as such.

Where are majority of your customers from?

All over the world, well, naturally New York, it’s the closest proximity. We get people from all over the world: Australia, Japan, New Zealand, France, Netherlands, England, Italy, and Germany, all over the U.S. We have people fly in from California maybe for a weekend, and they come and visit us, they purchase all they need and go back and we say, “how was your stay in New York” and they say, “We just came here for you guys and we are on our way back.” [Laughs] That’s gratifying!

You guys are a book of so many pages. For the vinyl aspect now, I noticed you guys have a lot of Makossa Records label vinyl. Do you guys own Makossa Records or do you just work with them?

We work with them, we are their distributors, we work very closely with them and we always have helped them to produce, more importantly to distribute. You can produce a record but if you don’t distribute a record it really serves no purpose. So we have an international network of distribution that we’ve always had and maintained, the record industry has gone through different phases, from vinyl to currently what it is. We’ve always believed and maintained vinyl as being the important aspect, a lot of the records you see here are from the ‘70s, ‘80s, and maybe ‘90s and these are all originals, you won’t find bootlegs here, as a matter of fact we appall bootlegs. [Laughs] It robs the artists of their income, it robs the artists of their inspiration, it robs the artists of their future, and that’s not a good thing, especially when we are speaking about a music that tends to be very fragile and important at the same time. Fragile because it’s a time capsule, the music can represent a capsule of time. Also because of the fact that as Africa is always developing, the music develops with it, so there’s no need for bootlegs. What there is a need for is to give the African music more expression and more room to grow. And that’s our purpose!

That’s great! I’ve been to so many record shops in the States because I’m a collector as well, some shops in Brooklyn, even New Jersey, Philadelphia, New Orleans, they have good records but they still have a lot of bootlegs. And I’m really impressed that since I’ve been coming here I’ve never seen any bootlegs. I’m really impressed.

Thank you, thank you very much, and you won’t, we fought against that since we started, there should be no bootlegs, we won’t support it, we never had and we never will. One of the things we’re concerned about as a retail or commercial establishment is that, the proprietor should be concerned with the commercialization of the music and in a way that it shouldn’t hurt the creator of the music. It’s kind of crazy to sell something that doesn’t support the artist because then the artist cannot support his or her craft. So we cannot say that we love the music but we’re still undermining the music, that doesn’t make sense, but we live in a time where commercialism begins to be, “How do I get a dollar?” Whenever I can or however I can.

In the industry there are so many people that want to get involved in the vinyl business by hook or by crook; how do you work with the artists or how does Makossa work with the artists to get royalties, etc.? I know people out there that will be like they got a record of an artist and buy the rights to the artist’s music, and produce the records, CDs but nothing goes back to the artist, some don’t even do this, some can just be producing this stuff and the artist doesn’t get to know anything about it. So does the artist get back something?

Well, first of all, I have to say African music, like most things in Africa, have been exploited. It’s been a systematic exploitation of Africa itself to this day and has never stopped. On the other hand, as far as the music goes we have worked with Makossa primarily as distributors, as I said, I know Makossa has produced music in accordance and in arrangement with each artist: through formal contracts, signed contracts and means of remuneration. And if one record sells more than another there’s more coming to the artist, depending on the arrangements that are made but Makossa was the first, I should mention, label for African music in the United States, one of the few in the world, as at that time, so the objective was to set up a system where by the artist could be recorded, and I know Makossa has recorded certain artists in New York City. While on tour, they’ve brought over certain groups and recorded them here, and there has always been an amicable financial arrangements so that the artist can continue to do what they know how to do best- make good music!

What are your challenges in the vinyl business?

We don’t have too many at this time, all of our music is original music like I said, from the ‘70s, ‘80s, ‘90s, so it’s stock that we have on hand that we distribute. As far as piracy goes, we are always on the look-out for that, you know people do have a tendency to pick up a record and copy it because they believe the world is a very large place, that no one will ever find out what they’ve done or who they are or where they are. [Laughs] And like I said, we have many partners all over the world and it’s not uncommon that sometimes we do have a call and say,” You know there’s a record that came out, check to see if this one is yours.” So we have that element, we know there’s a lot of piracy going on because people also believed that African music is something new and so they take the attitude that no one knows anything about it. Well sadly, people do know about African music, we’ve sold much African music through-out the past 50 years, so it’s not as if people don’t know, if there’s anyone being fooled it’s the person that believes that no one knows about African music. It’s generational, yes! There’s a new generation coming up who are discovering African music for the first time and we are happy about that also and so we have those kind of customers who come to see this large collection that we have and see that African music actually exists and it has done well, it has made its mark. When we look at songs like Michael Jackson’s where he used “Soul Makossa” and other artists, some of the music we have has been sampled; great Jay Z has sampled some of our artists, so it’s out there and it’s doing well.

Speaking of sampling, so Michael Jackson sampled Manu’s “Soul Makossa” and Jay Z sampled some of your artists’ music, do you guys have institutions or things set in place to make sure that the artist gets a check back for their material that’s been sampled?

That’s correct, where it concerns our artists, there is remuneration, we do follow through with it and if it’s a legitimate artist for sampling they will contact us to get a license and then we forward it to the appropriate avenues to clear it and so forth and so on and so. The main thing is that we’ve always attempted to bring African music into the 20th century; it should be treated and respected like all other music.

With the new wave of music, which is now so different from the usual, do you feel it has an effect on your sales, the new African music?

That’s a good point! Yes and no; no because the music you see on these albums can be considered as very classical, it is probably at the base of African music. In other words, when you speak of artists like Fela who created an original form– Afrobeat, you speak of artists like Franco and OK Jazz and Tabu Ley Rochereau, this is the indigenous pop music of Zaire, and the same goes for Cameroon, Guinea and Ghana. We have all of these major artists and we have to remember that it was at this time when African music was just beginning to be recorded and commercialized whether it was primarily for African consumption or not. The new music that has come out is very interesting, I think it has to do with the new generation but I think that people will always come back to this music that we have because it is the classical music. If you want to understand the new music you will have to come back to the old music and you would see the roots of it, how it developed or what it came from, which is more important. The genres of African music: highlife, soukous—what they call soukous, many years was known as rumba, or kiri kiri of Zaire, just to name a few, makossa in Cameroon, so you had all these different indigenous styles of pop African music and again they are the basis for all of African music and in a sense the basis for all music out there at this time, because there are a lot of musicians who have come to us, we’ve had people from the Grateful Dead many years ago come in and buy African music and were influenced by the sound of African music and we’ve had various other musicians over a period of time who have come in here to explore African music. So in that context we can only understand and believe that there’s been some kind cross-pollination of African music and Western music.

So sir, we spoke a lot about Africa, take us to the Caribbean because at first when I heard of this spot, I heard people say it was a Haitian record shop; I know you guys have lots of stuff from the Caribbean, so please throw some light on that.

Well, this is because they are all extensions of the same roots or the same mother—it’s African. Our original idea was not only did we want to have African music but, African Record Center should be a house for the derivatives for one of a better term of other African music. Haitian music whether it be compas or vodou, one of the traditional forms of Haitian music or rara, the carnival traditional music or Brazilian music—samba, you know, from the various schools of samba or whatever country has the African retentions, so based on that we began to develop and sell and collect Haitian music, zouk music from Martinique and Guadeloupe, reggae naturally from Jamaica, soca from Trinidad and other Caribbean countries. So apart from African music, we have all these other tributaries you might say of African music and we lumped them together and we called them African music from different locations.

What do you feel when you read in papers or something and they categorize African music as world music?

[Laughs] I like that one. Well we have never adhered to it in that way, African music is African music and African music is going to be African music, it is what it is. To try and label it or in this case mislabel it—“world music,” I don’t know if it’s saying it belongs to the world or the world created it, it’s kind of a play on words. We think, however, it’s a foolish attempt at whatever it is supposed to be because at best it’s ambiguous. African music is African music; it will always be African music!

You mentioned that there were parties when people started to listen to this music and that’s how it expanded. Do you still feel there are places or there are dance parties were people listen to this music or do you even organize parties?

Well, we don’t organize any now. We used to in the past, years ago, when disco first started there was this phenomenon of DJs. These were people who could carry their mobile systems and they would do house parties and street parties and they were responsible for getting the sound out because as long as a record could move their audience they would play that record. So they weren’t so much interested in where the record came from, they weren’t interested in the politics of the background of the record; they just play it because it’s good. So many times they might get a record from Europe and they would mix it into an African record and so there was this constant flow of sound. This is what I feel people adapted to, and African music is primarily among other things a very unique sound. So I think when people hear it, it’s kind of irresistible or it awakens something in them and that’s what makes it interesting.

We love music people! [Laughs]

Do you still see active DJs coming in here for records?

Yes, we get DJs who play in clubs and all, DJs that deejay in New York City has been here at one time or another and we like to give them a tour of what we have.

Last question, when you guys retire, are you going to stay in Africa or will you stay here in the States?

[Laughs] That’s a good question, we don’t know yet, we’ve had many offers to come to Africa. We’ve had offers to come there and help develop some institutions, we’ve been in Africa so many times just about maybe every country in Africa, but to do something concrete beyond this, we are thinking about it very seriously. It will take us: why and how and when? Definitely, we are heading in that direction.

I think it is a great one; Thanks you very much, sir.

Thank you too, our pleasure, on behalf of myself, and Rudolph Francis and Roland Francis, and Roy Francis, we appreciate it!