Dr. Austin Emielu is a musician and an associate professor of music at Kwara State University, Malete, Nigeria. Alongside producer Morgan Greenstreet, Dr. Emielu co-produced our latest Hip Deep Nigeria program "Edo Highlife: Culture, Politics and Progressive Traditionalism." Morgan and Austin traveled across Edo State in December and January of 2016-17, meeting renowned Edo highlife musicians including Sir Victor Uwaifo, Ambassador Osayomore Joseph and Alhaji Waziri Oshomah. Austin is from Isoko in neighboring Delta State, which used to be part unified with Edo as the Midwest Region and later as Bendel State. He came to Benin City in the 1980s to work as a musician, and later returned for post-doctoral research into Edo highlife music in 2011-12. This text interview is compiled and edited from multiple conversations between the producers over the course of their fieldwork. All photos by Morgan Greenstreet.

Morgan: So, we’ve been traveling around Edo State for the past two weeks, meeting many highlife musicians. There is a vibrant live music scene here in Edo State, which seems relatively unchanged since the late 1960s. One of my main questions is, how do highlife musicians stay culturally relevant in this region?

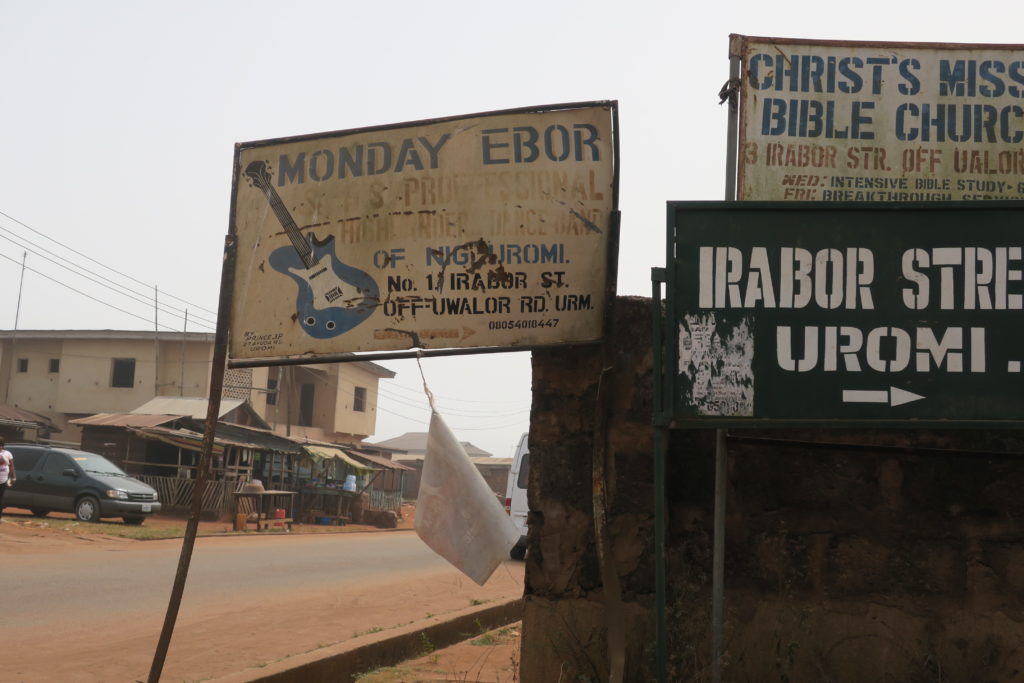

Austin Emielu: What caught my attention in the ‘70s when I used to come to Benin City is that along every street at every junction you would see signboards for “So-and-so Dance Band” with the signboard and arrow pointing to the home of the musician. As we went to Uromi now, you could still see signs that said “So-and-so dance band of Uromi," “So-and-so dance band of Irrua.”

Signboard for Monday Ebor in Uromi, Nigeria

Signboard for Monday Ebor in Uromi, Nigeria

So in Benin here, you have so many bands, in most of these bands most of these musicians live and practice their art within their communities, within their towns. So-and-so dance band of Uromi, he comes from Uromi and plays his music in Uromi. So they are not superstars, they're not musicians that are hyper real. These are community folks, living within their communities and contributing to community life. So what attracted me was the sheer number of these musicians, and the idea that they are within their communities, playing what you describe as popular music even within the villages, and contributing to the social, cultural and economic life of the people. The trend usually is for musicians to move from the villages to the city. So, what’s very unique here, is that these people, apart from a few who try to sing in English, sing in the local dialects. So they are like musicians within their communities, continuing traditions within their communities.

Austin Emielu and Morgan Greenstreet with Akobeghian, a popular singer in Benin City

Austin Emielu and Morgan Greenstreet with Akobeghian, a popular singer in Benin City

Why is that?

Well, if you study Edo history, it is very rich in culture, it was one of the very, very big empires in those days, the Benin Empire. So the political institution has been strong, and that sense of being a kingdom, an empire has been there, and the people are deeply rooted in their traditions. They are noted for music, they are noted for fine arts, for sculpture, for iron work.

How would you describe Edo highlife?

When we talk about Edo highlife music, it's a very broad generic term that includes various sub-ethnic types, because Edo itself is a pan-ethnic identity: Within it you have the Bini, you have Esan, the Owan, the Etsako, Okpameri. So what makes the Edo highlife music unique is, they have a very deep connection to the roots.

You know, highlife, it’s a West African musical phenomenon and people come in from their ethnic backgrounds and domesticate it within their ethnic musical sensibilities.

That's why I've tried to theorize, that there is nothing like highlife music, but highlife musics. Since highlife is West Africa's pioneer popular music, everything is said to have taken root from highlife music.”

O.K., so generally, let me talk about West Africa, or maybe Africa as a whole, black Africa. What we had was traditional music, indigenous music; we call it folk music. We have social music, we have sacred music for all occasions. And now the European contact, you know. And now the other foreign influences coming, what we might describe as the forces of modernity, to try and transform this music. So what happened was, with these influences coming from abroad, through radio, through records, through traveling musicians and all that, the guitar was introduced. So the guitar became the organizing principle for the new African sound, that we now hear as popular music. So, before the highlife, it was traditional music, and then the guitar came, first of all as an unplugged guitar, the acoustic guitar, and you play with traditional instruments and with just the guitar. Later they started fixing a microphone to it, before the electric guitar came. So what you find now is some form of traditional music, but reorganized using Western technology and musical instruments. So when the guitars were introduced, the guitar became a way of modernizing what is otherwise traditional.

A neo-traditional group performs at a wedding ceremony in Benin City

A neo-traditional group performs at a wedding ceremony in Benin City

Who are the Edo people?

Well, the idea of "Edo" is both a pan-ethnic identity, at the same time specific to Bini, the Bini people, Bini-speaking people. Bini is the language, Benin is the town, where we are right now. So the Benin empire had this capital, in Benin City, and Benin is supposed to be the home of the Edos, so the various ethnic groups are said to be under the Benin Kingdom. So, the idea of Edo itself, is synonymous with Bini, the language, as a language group, as a people, at the same time it represents the whole state. For the government to have created Edo State means that these people are people of Edoid extraction, the Edo language group.

A cultural troupe performs at the palace of the Oba of Benin

A cultural troupe performs at the palace of the Oba of Benin

So, what is the importance of the Oba [King] of Benin?

The Oba of Benin is like the father of the whole Edo people, he is the traditional, spiritual, and political head of the Edo people. He holds a very powerful position, which every citizen of Edo acknowledges. The Oba’s word is final on everything concerning the traditional life of the people. All the subgroups are under him, they acknowledge his power, so it also establishes the Bini hegemony, in the power relations that exist between the Bini and the rest. The Oba of Benin is a first class Oba and no other one in Edo is a first class Oba.

What does that mean?

He’s under the federal government, so he’s rated very high. So all other kings in Edo are under him. Because the Oba of Benin, who has been the king of the Benin Empire, is regarded to be the father of all, the Bini are said to be senior. History has it that all the other subgroups, were once together, under the Oba of Benin. Maybe the Oba decreed something, and people couldn’t bear his policies, so they left, what we call mass migration. People left, the Esan moved, the Etsako moved, and all, but they still agreed to the Bini hegemony. The Binis are said to be senior, so you’ll hear terms like: “Edo odion” “Edo is senior,” and among the Esan, you’ll hear “an Esan man will not spill a Bini man’s blood, will not kill a Bini man.” Edo society is also very traditional, extremely traditional. It's a convergence of tradition and modernity. For example, if we have a gathering now, maybe if we go to Uromi, and there's a ceremony, and they present kola, they will ask, “Is there any Bini man here?" because it's only a Bini man that can break the kola. So even if the boy is 5 years old and he comes from Benin here, he will be the one to break the kola on behalf of the Oba of Benin. So these power relations are there.

Getting back to highlife music, how did Edo highlife get started?

So, it is Victor Uwaifo that pioneered this kind of highlife. He was not the first to start it, but he made it very popular, this kind of highlife, that kind of modernized Bini, Edo music. So he brought the music into the mainstream of highlife.

He became very international with his song, “Guitar Boy and Mami Wata” and he was said to be the first artist to win a gold disc in Africa, meaning he sold over 100,000 records, that's a gold disc, here. Many of the musicians I worked with outside of Benin told me that they were inspired by Victor Uwaifo. Benji Igbadumhe told me that Victor Uwaifo used to come to Auchi to perform, and each time he came to perform it was wonderful. Then they were also using his recordings as a way to promote products. When they came to sell products in Auchi area they would put a film with Victor Uwaifo performing, and people were really excited. So he inspired a whole lot of Edo musicians, far and wide. [Read our feature "Sir Victor Uwaifo, Superstar: In His Own Words" for more on Victor Uwaifo]

And most specifically what is unique about Edo highlife music, is that it sort of deconstructs the idea of highlife being an elitist phenomenon. Highlife itself came as a West African socio-musical phenomenon, and from there it became a national model, and from there it went down to an ethno-national model, so highlife is like a tree. So Sir Victor Uwaifo was playing in the mainstream current of West African highlife, coming from his own background as an Edo person. Then the musicians that copied from him did not go into the kind of highlife, kind of elitist level that he did, they brought it down to the grassroots. When it started first in Benin, people were quick to say “obito bands” because they played in funeral ceremonies. And that's where it had much more cultural resonance with the people. Rather than play at the Joromi hotel where people would come and pay tickets and enter, they could play and serve as a new form of traditional music in various social or cultural contexts in the society.

King Benji Igbadumhe Live in Iluoke, Nigeria

King Benji Igbadumhe Live in Iluoke, Nigeria

King Benji Igbadumhe live at an age-initiation ceremony

King Benji Igbadumhe live at an age-initiation ceremony

What does obito mean?

The idea of obito, obito means obituary. These bands developed as a contradistinction to those highlife bands that were based in hotels. The ones that are based in hotels play on weekends, in the evenings and they were not mobile. Most likely the instruments were owned by the hotel proprietor. So, there was a need to supply the same music, to use the same music for community events. In this part of the country, burial ceremonies are really very grand, burial ceremonies. So these bands developed as a way to meet that need, to fill that niche.

Of course, the hotel bands, you expect them to play a variety of music, some contemplative, some for dancing, but the idea of obito, is people want to dance and celebrate the deceased. So it was essentially a dance band kind of thing, a dance-oriented thing. Before this modern dance band came, they were hiring traditional groups, but of course with modern technology, that kind of music cannot really move people to dance much, now you have the technology of sound reinforcement, using microphones, where you can reach a broader audience. So why not incorporate this music in?

So people started learning to perform in burial ceremonies, and in doing so, which was considered an inferior version of highlife, because usually they're using guitars, guitars and drums, when the highlife bands were playing brass and all that, so they were given the inferior label "obito bands." But somebody like Agbakpan Olita has come to legitimize obitos, he calls himself “Obito Commando.” So he's happy to say, “I'm the commander of the obituary groups, so if you call me for your obito, it’s confirmed,” as we say in Nigeria, it’s confirmed [Laughter].

So it's supposed to be a derogatory name for an inferior kind of highlife, but at the same time it was filling an important need in the community here, the need to use dance bands for burials. And some of these bands play overnight, for the burials. So I think that's what really encouraged the explosion of these dance bands in Edo here, because burials are all over, so people were setting up bands to fill up those gaps, to meet those demands.

But when you hear this music, it's not that they are singing dirges, or funeral songs, it's just that, "I know how to treat you when you do your obituary ceremony, I know how to give you good music." So it's usually a night of dancing.

What would a band like that sound like at a funeral?

No, they just play general music! The family is already buried their dead; especially when the person is old, the family is sad that they've lost somebody but the social aspect is weightier than the emotional. People travel from different places, “Oh there's going to be one obito in Uromi today, and the obito is going to be heavy! The man's children are coming from the U.K., or coming from Europe.” People come there because it's an opportunity for free drinks, to hear good music, dance, and look for new girlfriend and stuff like that [Laughter].

Dr. Afile live in his village, Idikhala Ewoyi, Uromi

Dr. Afile live in his village, Idikhala Ewoyi, Uromi

Social life is much here, and those types of events are where people get their social life.

And it’s open to everyone?

Oh, it’s open to everybody! Even if you do print invitation cards, it doesn’t work! The invitation is just to set up your speakers and put up your canopies, that’s all! People just come, all people, even the destitute, those that have mental problems, everybody comes there. And also people who sell things: The ceremony is going on, the photographer is there taking pictures and collecting money from the audience; people are selling things on the side, cigarettes, chocolates and things like that on the sides; the video man is there, all manner of people! And the musician comes with friends, so when you're playing on stage, some are drinking beer behind the musicians. So it's a real social gathering. And then the rainmaker is there, to make sure the rain doesn't fall.

What is that?

Yes, the rainmaker! If you want to do a ceremony, you have to get a rainmaker who holds the rain, so the rain doesn't fall. He will light a fire somewhere, chant and do incantations, you give him a bottle of maybe schnapps or whiskey, he is drinking and holding the rain.

And what if it rains?

Oh, it scatters the ceremony!

What if you hire a rainmaker and it still rains?

Then he is not a good one [Laughter].

Can you describe what happens at a typical performance in Edo State?

Music-making in this part of Africa is a site for business, it’s a site for social interaction, it’s a site for so many things going on. So, in a typical musical performance, it’s not just the music that's going on. In the dance bands that we are studying, it's a community of its own: You have the bandleader; you have the musicians or instrumentalists; you have those that pack instruments, what they call "packers;" you have a sound engineer; you have a man that drives the truck; you have the manager. It is a whole community of support, there may be friends and close associates who come there. At the end of the day everybody gets some free food, some free drinks, and makes some little money for themselves.

The band is seen as an economic enterprise, and people connect to it from different angles. Even the people that rent the instruments, if you don't have instruments of your own, and those people will make money from you. The person who works on the generator so you can power your instruments also has a part to play. The master of ceremonies. Then the dancers, they're just connected, they are not really professional dancers in that sense, they're not trained dancers, but they’re also connected.

So the musician becomes a center, a hub, around which many other activities revolve.

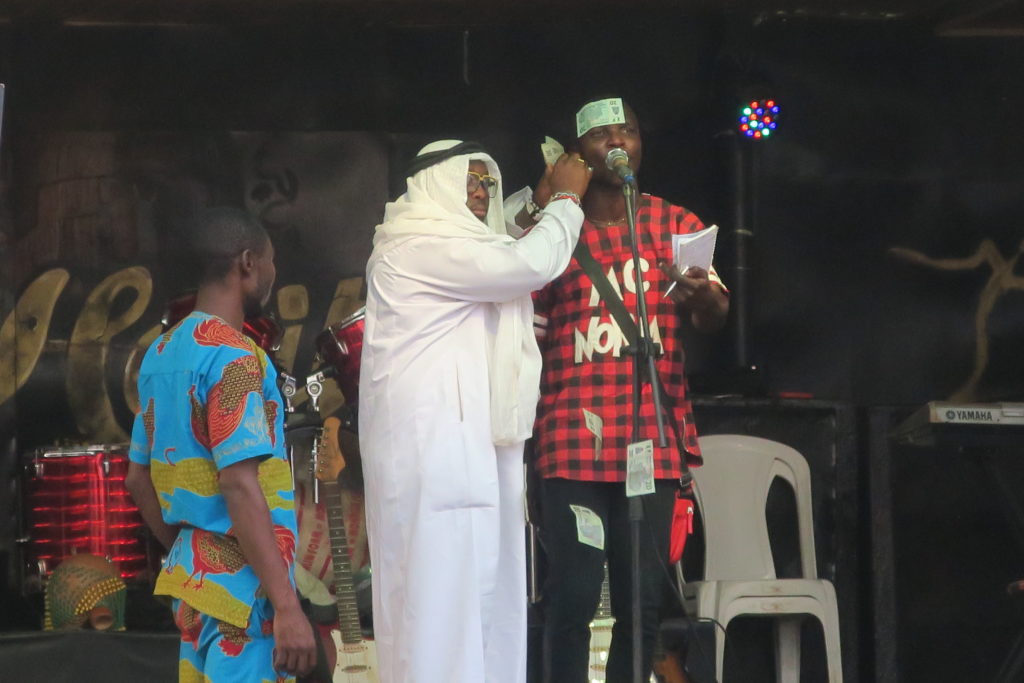

If you take that further, you also find people who sell various items, some people change money, because spraying [giving musicians money during performance] is part of the musical performances here, so you've got to spray money, paste money on their forehead. So, we know that, if you want to spray 500 naira [approximately one U.S. dollar], it is not fashionable to just put 500 there and go away. So you want to break 500 into smaller denominations so that you can stay there and begin to spray, literally, you are spraying. So somebody offers a service to break it down for you, because it can be difficult to get change. So their business is to go look for change in smaller denominations, and charge you a percentage for the exchange.

A money changer

A money changer

Then the caterers who serve people food, the photographers, some of them are not hired, they are just freelance! All you need to know is where the event is happening: You take your camera there, you take pictures, all you need is for someone to agree for you to take a picture, and then you quickly go to the lab and print the picture before the ceremony is over, and you come around, looking at the people's faces in the picture, and you say “This is you.” They say “Oh, fine, how much is it?” “200 naira.” He pays.

So you find these people there, freelance photographers, you find the videographer, too, people who rent canopies, everybody gains. You may find people selling, in case you weren't satisfied with what you are given there, the drinks that you were given, we can we can sell you extra drinks, we can sell you smoke, some people are also on the side, so maybe chocolate sweets and all.

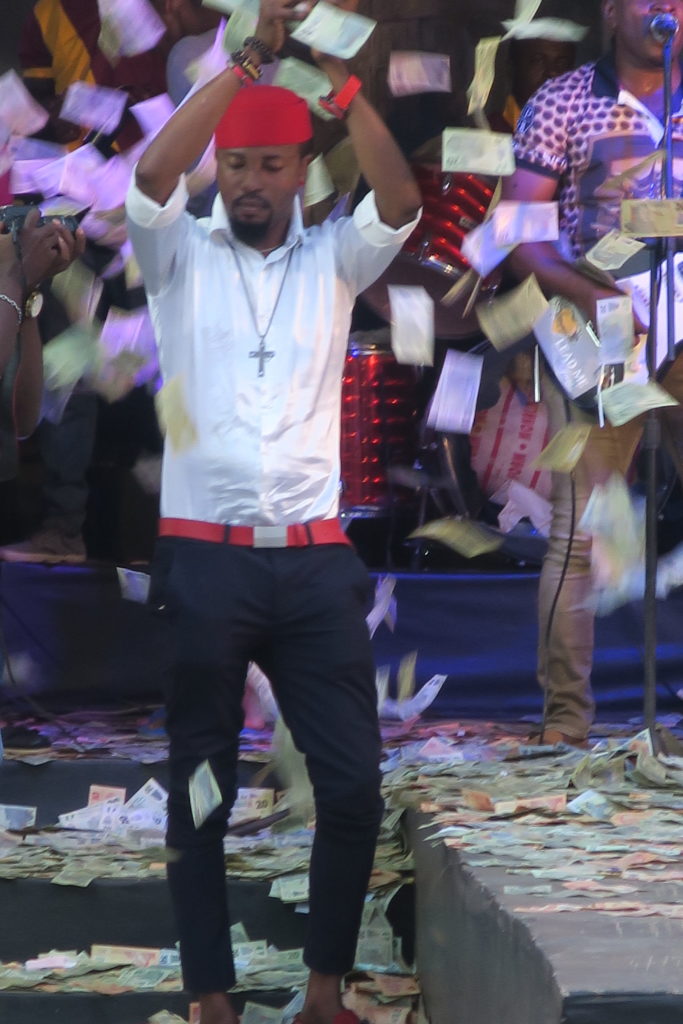

Can you describe the phenomenon of spraying? We've done it a bit in the past few days, but I've noticed people have different styles. Some people walk up really slow, some people come and just throw a handful of cash in the air, sometimes somebody will just be throwing cash as if it doesn't matter, as if they're not even looking at what they're doing.

Before you come to spray sometimes the musician will call your name, like "This is Professor Austin,” so as a mark of reciprocity, you get up to say “Thank you for acknowledging me.” So within the community, the musician is providing service for the community, and as a way for to say thank you, we also give back. So apart from the performance fee, which is not too high, the spraying is what really makes it communal: "Oh musician, we really appreciate you."

In the first place, if somebody invites a musician to perform, apart from paying the fee, they musician will tell you, "In advance, you have to give us three cartons of beer,” for example, “Two crates of mineral, one cooler of rice, one cooler of pounded yam, one cooler of this…” It's agreed. So at the point the musician comes there, the hosts supply them with all that food. It's also a mark of reciprocity! If I invite you I should give you food to eat, hoping that when you're well fed you will perform well. Most times, the food they request for is far more than what they need, and that's where the hungry communities connect. So the musicians are playing on stage, and many people are eating offstage, or behind the stage [Laughs].

So, the level of spraying is, they call you as somebody who is important in the society and you come out to spray, or you feel moved to spray. So, this is a community of support for the musician. As people come out to spray, they also create their own kinds of identities and aesthetics. When you come out to spray, some people stay there very long, to show, “Look, I'm a cool guy, and I give you my money this way.” Some come very excited and they throw the money in the air. Some come, the manager will tell you specifically “Don't put the money on the forehead of the musician,” sometimes they think that they will poison them, some kind of voodoo attack, I can spray you money now and you will just fall down, so they ask you to just throw the money on the ground. If you came on your own to spray, the manager will quickly ask you your name, “What's your name, sir?” And then he goes back to tell the musician “This man is Morgan Greenstreet from New York, and he weaves that into the song, extempore, “We want to welcome Morgan Greenstreet…" and begins to sing like that. So it's considered improper for you to go to community performance like that, musicians are playing and you don't get up to spray them money. Even if you pay them millions of naira, you must get up to spray money.

The Untouchable album release party, Benin City

The Untouchable album release party, Benin City

What does it do for the sprayer? Because they're also getting up in front of their community and showing their money.

In a way, it helps to reinforce social stratification in the society. For example now, when you're spraying, we are looking at you, the audience is looking at you, the community is looking at you. “How much is he going to spray? Oh he spent 30 minutes spraying, he has a lot of money!” Somebody goes there, he spent two minutes, “Oh, this guy’s not rich.” Then the denominations you spray, “Oh 20 naira, 30, oh he was spraying 500 naira and he spent 30 minutes spraying, oh!” So in a way, it reinforces the social stratification in the society, which I think is not too good for the system, because sometimes people struggle to spray, to give the impression of doing very well, when in fact they are not.

And those who get money from illegal sources, that's the best way to spend your money, because you tell the people, "Yes I'm rich.” But those who work really hard for their money sometimes find it hard to just throw it away.

In Benin City, we attended an album launch concert for the musician known as The Untouchable. The stage was covered in money, people were just throwing money on the floor. Is he an important musician in Benin? Does spraying reflect on the popularity of the musician, whether they get sprayed or not, whether they're considered a good musician? Does it reflect their worth?

No, it's not a matter of how good you are. The musician must connect with certain groups, so at the Untouchable concert, you saw this club from here, that club from there; all he needs to do is use a bottle of drink and some money to invite them. So they look at it as a compliment for you to invite them to attend, as an honor to come to your event. So they come to support you, it doesn't matter if you are fantastic. Some of the musicians we've been working with, I don't find them really fantastic in terms of an international stage, but the community feels that they're doing something.

Akobeghian live at a wedding in Benin City

Akobeghian live at a wedding in Benin City

They’re relevant.

Yes, we need them in every ceremony we do. We need them, so we have to support them. So they come just to get their support. For the musician, he needs to build up that kind of social capital by connecting with certain groups. First of all, the family member will come, family members will tell their friends, “My brother is doing something,” people belong to one or two clubs, he tells them. So those kind of performances become opportunities for people who are connected either directly or indirectly with the musician to come and show their appreciation, it has nothing to do with how wonderful the performance is.

In terms of the performance aesthetics, the first thing that I noticed is that there's a wall of speakers, but very little space for the musicians to stand, or the dancers to dance, compared to how much room the speakers take up. Can you talk about that and the sound quality?

Yes, when we saw Dr. Afile perform at the Citadel Hotel [in Uromi] I wanted to see the way the band was performing on stage, see the drummer, his nuances, the guitarist and all the moves, but only the musician himself was visible, and there was very little space for anything to happen. So, you begin to wonder what is really important about the performance? Is it the sound, or just the visual aesthetics? Is the importance attached only to the owner of the band, the lead singer? I think that it does speak a lot about the community sense of aesthetics. Is it the lyrics that you're listening to? Or is it the beat? What actually moves you, how do you rate a good performance?

Why is the music so loud?

Well, in this part of the world, loudness relates to power. It’s war of sound. The musicians prepare themselves, because you could get invited to a place where three bands are playing, and if your instruments are not strong enough, you are defeated, so to say, literally. So you prepare, like your arsenal, and you're ready to give it out. So it's considered here, that if the music is loud and powerful, it moves people more. So there's not much attention to people's auditory sensibilities. Even the frequency balance of the speakers, as long as the sound is heavy people will come and look at the wall of speakers, and say, “Wow, the musician has great instruments!”

It's a carryover from the Yoruba musicians, they build a wall of speakers, mountains. So they have also copied that. This place was part of the western region before, so the Yoruba influence has always been very strong, [the Edo] are a small group attached to a larger group. Even now in town here, in Benin, you still have Yoruba musicians and people playing juju. Then in Auchi, Akoko-Edo, they speak a lot of Yoruba there. These are the kind of mutual borrowing and exchanges between neighbors.

The Edo is also a smaller minority group, so there might also have been more pressure on them to adapt to Yoruba musical forms.

Yes, very good, and the Yoruba started the arts much earlier than anyone, the bands used to tour here, the theater groups used to tour here, Baba Sala and the rest of them. They brought theater here, they brought these influences.

Here is like a point of convergence for music from the Igbo speaking areas and music from the West, the Yoruba speaking areas. So you have a mix of all this. For a long time Edo musicians used to go to the East to record, and many of these musicians also sojourned in the West, in Yoruba areas for some time, Lagos and Ife and the rest. So the Yoruba influence is [strong]. For example if you go to Uromi now, you'll find that they're starting to use the talking drum more in their music. But again, they had to domesticate the talking drum. This time it does not talk in the literal sense, but they use it to beef up the rhythmic density of the music.

Within the Yoruba society, it’s used as a speech surrogate, and if you're learning to play the talking drum you must first of all understand the Yoruba language and then you will begin to learn proverbs, declarations. Like in those days, on Radio Oyo, you would hear [Sings drum language]. T’olubadan ba ku ta ni oj’oye. That was the signature for the news, literally translated as, “If the king of Ibadan dies, who will be the king?”

So if you play in a Yoruba popular band, the talking drummer is talking, and people understand what he's saying. But among the Edo here the talking drum is just used to beef up the rhythmic density, because Yoruba music is rhythmically very rich. So now if you're just using drum kit and congas, it looks empty. So you put the omele, you put the talking drum, some people use the sakara. So if you go to Ora, you meet somebody like Orlando Oviegwa, he plays what he calls Ivbiagogo. He combines the Ora traditional instruments with borrowed talking drum and sakara from the West, and a keyboard.

Do they have speech surrogates here in Edo?

Not that I know of, there may be other forms of communication through musical instruments, but it's not in the sense that Yoruba use it. They can use it to abuse you, they can use it to tell you something you're doing wrong. But they have other ways of communication that I may not be aware of.

As we have seen talking to musicians all over Edo, their music is broad enough to accommodate external influences. My theory proposes you take the outside forces, or outside resources to enrich the inside, rather than destroy the inside. For example, the talking drum that the Edo musicians are using now, it's not destroying the ethnic aesthetics of the music, rather it is beefing up the rhythmic density in providing an impetus for dancing. So it's what you call selective adaptation, selective borrowing. Musicians have not started rapping in their music, although they hear hip-hop all over the place, it doesn't make sense now to them. But something that makes sense within the cultural context in which they operate, is something that they can use. So when you add talking drum into Edo highlife music, it doesn't create any problem for the cultural appreciation, or aesthetic appreciation of the people within the culture. So it's working. When they put keyboard, it doesn't disturb it.

So we’ve seen a case where the outside resources are harnessed to enrich the inside rather than destroy. So through my theory, you find that there is selective adaptation, taking only those things that enrich. So you can see that gradually, they’re taking things from the outside to enrich the local tradition, yet they're not giving up on their tradition. A Benin musician will not now change to a Yoruba musician.

Osayomore Joseph live at a wedding in Benin City

Osayomore Joseph live at a wedding in Benin City

Can you tell us how Edo highlife connects with your theory of progressive traditionalism?

For the past two weeks we've been working with musicians in different locations, we’ve been trying to establish the connection with the ethnic traditions, trying to establish the prevalent themes in their music, we've also talked to personalities to try to understand their driving force, understand how their music communicates to their communities. So what we found at the end of the day, when we talk about Edo popular music, the dance band that we are studying, it's a case of what I describe as progressive traditionalism. Where there is a connection between tradition, innovation and modernity.

Rather than a linear progression of tradition to modernity, it's like a circular development,

because the tradition, through innovation, changes form, presented in the new media, in a modern context. In 10 years time, if we come back here, what we’re calling the modern now may become the traditional. So the generations ahead will redefine again. I find this quite interesting, particularly the way it defines the aesthetic sensibilities of their own people.

What do you mean by that?

Well, what is considered good music within every culture? It is the culture that tells you what is good music, who's a good drummer, who's a good singer, who's a good composer, who's a good dancer. These are culturally specific. So, at a particular point, this is a benchmark for aesthetic appreciation, “a good singer must…A good dancer must…” With these innovations in development in the modern context, you find that this framework will begin to expand. We were hearing saxophone in Benji Igbadumhe's music, but it was not there before. Are people going to accept? Are they going to resist? The aesthetic framework keeps expanding. And one interesting thing, how the community has come to accept this new music as their own. The people I talked to in the field, they say, "Oh this is our music, it speaks to us in ways that we understand.” That's what they tell me. They don't say, “Oh this is by bastardizing our music.” No, they say, "This is our music!”

So these guitar bands, these modern bands are expanding the aesthetic framework, and also the cultural sensibilities of their people, and the people have come to accept them as their own. So they are redefining what is acceptable, musically, within the community. Even old people will say, "Oh, this musician said that.” So they take their philosophies from the musicians.

So in my own view, what they play now, is a new form of traditional music. We have heard the stories how they drew so much on folktales and histories and legends and traditional forms, in some cases we have seen how the traditional forms exist side by side with the popular ones, that's the most unique thing about Edo highlife music. So my theory negates the idea of rigid traditionalism, and that's what ethnomusicology in Africa set out to do in its earliest beginnings: Collect the music in its pristine stage, preserve it, and protect it from being contaminated. So that’s rigid traditionalism, but Bruno Nettl said, “Change is inherent in any musical system.” In a world like this that is seamless, open to influences around the world, your own music, your own culture cannot remain static. So, also building on Kofi Agawu’s theory of self-conscious renewal, these traditional forms at some point have to find a way of renewing themselves, and to me, these musicians are providing that driving force, to renew the traditional forms and present them in new media, in new contexts. So my theory of progressive traditionalism, is that a traditional form, a musical form can develop progressively without disconnecting from its traditional roots. In doing so, I’m problematizing the distinction between the so-called popular and the so-called traditional, as two categories that are in opposition, as two binary opposites.

I also see the traditionalism in the apprenticeship system. What is the apprenticeship system like here?

These bands are taken as trades. O.K., I feel like I want to be a musician, so where do I start from? I must go and try and be an apprentice, that means study under somebody. So in the case of Benin musician Akobeghian [who told us the story of his apprenticeship with Akaba Man] you come, you pay some money, they pray for you, they take you in as an apprentice, you sign a contract, maybe you're going to spend two years. At that time you’re a boy. Maybe you start with packing instruments, then you're watching, then you learn to play the clave or the maracas, some minor instrument. Then you decide within that band what instrument you want to learn and then you understudy somebody.

Being in the band, they are also molding your character. Akobe told us that he was paying for his boy’s house rent, until he found a girlfriend in his room, “So now you’re big boy, you can pay your own rent.” In other words he did not behave well, so they are also trying to mold his character. So the apprenticeship system is an informal way to study music, an informal process.

It seems almost formal though.

Yes, except there's no time to sit down and study, except maybe the instrumentalist takes you on. You learn by observation, from observation you learn to do, under the correction of somebody who is a master. You find that in traditional society, too. A child in African society, when you talk about enculturation, learning your own culture, it starts by observing what the elders are doing, so when he begins to dance, take a step, the child also takes a step, so it is also borrowed from the traditional setting.

Paulina Ogenete and her traditional asonogun group

Paulina Ogenete and her traditional asonogun group

Paulina Ogenete, who we talked to the other day [in Uromi] she also said, “At 6, I was already performing with my father," so she must've learned the dance steps from the father. So it's part of the traditional approach to education.

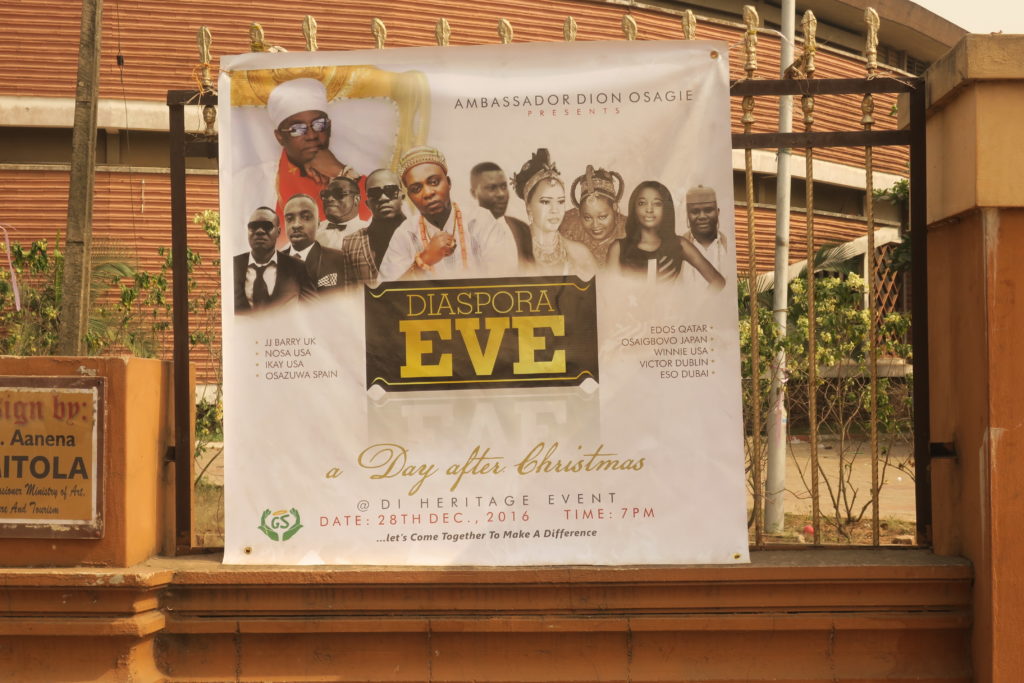

A number of the musicians we met also told us how they perform for Edo communities in the diaspora. So it seems to me that while these musicians are very local, they are also connected internationally, at least to the Edo diaspora?

There is a way in which they have also become global in the sense. People come from there and pick them to perform and bring them home here. So these musicians who did not go to school were not highly learned people, also have the opportunity to perform abroad, and make some money, and they bring the money back to develop their own communities.

They not only serve the community they're in, they serve a diaspora community. So if you pick up typical album, you will see the addresses, “Available at so and so address, Genoa, Italy,” the address of distributors at some address in Europe. In a way too, I think the people appreciate them because they are keeping the tradition alive. Through innovation, because if you lose your musical identity you're also losing your roots, so as they go abroad they still want to share music from home, and so these guys provide them that.

A special tent for diaspora residents at a wedding in Benin City

A special tent for diaspora residents at a wedding in Benin City

Many Edo people live in the diaspora, or come in and out of the diaspora. They come in like this around Christmas, you feel them around. They have a large population in Italy, in Germany, in Holland, particularly in Europe. Some work there, send things to their relatives here. For example, at a time all the buses here were sent from Europe, Mitsubishi L300, because the transportation system here was almost collapsing, so many of the people were going abroad, and they would buy a bus and send it. So actually, the Edo community is being sustained by the diaspora community, let me put it that way, because there’s hardly any family that doesn’t have somebody abroad. Typically, when you see an obituary poster, you will see "He is survived by five children…U.S.A., this this this, Netherlands, and so on,” so this is listed as a kind of social status for that family. And during such burials, you may see these boys around, so you’ll see this effect of the diaspora community, to spice up the social life of the people.

Event geared towards diaspora residents who have returned for the holiday in Benin City

Event geared towards diaspora residents who have returned for the holiday in Benin City

Another facet of Edo highlife music that we’ve been looking into is musician’s engagement with politics, either as praise singers for politics or writing critical, activist music. We know of at least four current musicians, Osayomore Joseph, Advisor Nowamagbe, Johnbull Obakpolor and Ambassador Joker, who make critical political statements with their music. I don't see this level of directness anywhere else in the country.

Yes, that's true.

So is there anything particular about Edo State?

In this part of Nigeria people are bold to tell you what they feel, they are not afraid to tell you, “I'm angry with you," they don't know how to make pretense. Everybody's bold, everybody's articulate. And the people themselves want to hear frank talk, they don't like things being veiled, they like things direct, say it as you see it. So they say what the people expect to hear, and they support them. So that's a cultural pedestal from which activism springs up.

Johnbull Obakpolor and Morgan Greenstreet

Johnbull Obakpolor and Morgan Greenstreet

While Johnbull Obakpolor said nobody has influenced him, he started from childhood, he has also found support from his elders who have been doing it. Because he said, “Osayomore Joseph is my father. Advisor Nowamagbe is my father,” so there's some form of encouragement. Ambassador Joker does not have those senior colleagues who are into activism, so he is alone. But here you have community support from the elders. When asked I Obakpolor, he said, “If I have a problem, I called them.” So that one also encourages activism.

Someone like Osayomore Joseph, he was in the army, he said, "I worked in the Army, where the business of the Army is to kill people, so if you want to kill me I'm not scared.” So he came in with a certain level of boldness. “I’ve been in the Army, I fought wars, so what are we going to do?!” So when General Abacha came to pick him up, it's not strange, maybe he’s already slept in the guard room many times! And Advisor Nowamabe would've picked up from him. And remember these are Bini people living in Benin, so that is a certain level of community support. The traditional religion is very strong there, they may have also gone to do some reinforcement, some black power reinforcement. So when you plan for them, they are also planning.

Osayomore Joseph

Osayomore Joseph

So, what I'm saying, it's not enough to just wake up and say, "I feel my government is not doing well, I must talk.” You better think very well: Do you have the political clout? Do you have the financial muscles? Do you have the social capital? These are issues when we talk about getting involved in politics. When the government mobilizes its machinery, it will just run over you and nobody will talk, people will go about their businesses.

We’ve also heard a number of musicians, including Waziri Oshomah and even Advisor Nowamagbe sing in praise of politicians.

Yes, there is this theory that musicians sing the state: Singing the state, that means singing in praise of the state. I argued in one of my articles that singing the state looks as if you're biased politically, but I was trying to theorize that if the government is doing well and people are feeling the impact, there is nothing wrong with the musician singing the state. So this is one of my ideas playing itself out in actuality. When the government is doing well, the musicians sing the state, they praise the government, when they’re not doing well, they come around to say, “Hey, you’re not doing well.”

A signboard for Alhaji Waziri Oshomah's album Change, pictured with former Gov. Adams Oshiomole

A signboard for Alhaji Waziri Oshomah's album Change, pictured with former Gov. Adams Oshiomole

I was surprised to hear from Osayomore and Obakpolor that some of their political music really connected with people, and people supported them, because what I've heard elsewhere in Nigeria, in Lagos for example, is that nobody wants to hear musicians sing about the obvious difficulties that everyone deals with everyday: “When you leave the front door of the house everything is problems, so when I listen to the music I don't want to hear about problems I want to feel free and dance, I don't want to hear you telling me about the things I already see in front of me.”

Yes, yes. I've also argued, “Can you do a research and tell me to what extent singing political songs have changed society? Does singing a political song create political change? As a direct consequence? So music is only a vehicle, music gets people thinking. Music does not create the political change, but it may set it up. So you can do all the political songs in the world, what Fela sang about, people celebrated him, but has the country changed? He fought and fought and fought and we’re still where we are.

So I think that music is an art; just do it, play your music and go, leave politics for politicians. The musician is trapped in a complex web of global capitalism, career sustainability, and a sense of civic responsibility. So how does he or she coordinate all this?

Global capitalism: I have to make money as a musician, music is my business. Career sustainability: I want to build a career and sustain it for a long time. And a sense of civic responsibility: When someone in society is not doing well, as a mouthpiece I should be able to speak out. So what I was advocating for in that paper is that we should empathize with them and not crucify them, because at the end of the day, when Fela was thrown off of his building, we were sleeping in our beds and he was the one that was beaten.

So, if you had to summarize, how and why do highlife musicians thrive in Edo State?

There is enough community support, and the people love music, they love dancing, and every event in society here is celebrated with music. Then the economy is also based within the community! Either here or in the diaspora. You heard them say, Victor Uwaifo and Osayomore Joseph, “I was in Lagos, but I came here because I thought I would do better here. It has more meaning to me to be here.” Monday Ebor said, “I had to come home. I've been playing with Sonny Okosun all over Europe, all over America, but if I'm going to be relevant in music in Nigeria, I better go to my roots.” And he came back.

You heard Johnbull Obakpolor, “Take me to America, take me to Europe fine but I won't live there because I'm O.K. here.” The point I'm making is, there is sufficient support in terms of patronage, in the economics of doing music here, and cultural resonance and social significance. Social status and social capital, everything is here.

Thank you so much!