Reviews July 25, 2006

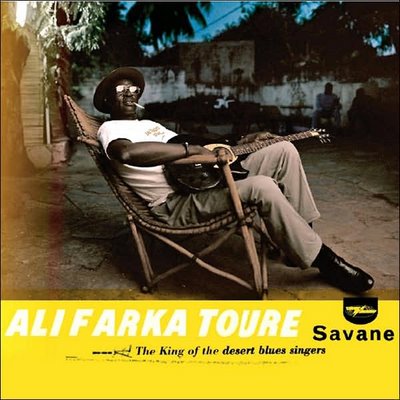

Ali Farka Toure, Savane

Just over a year before Malian guitarist and singer Ali Farka Toure died of cancer in March 2006, I visited him at his second home in Bamako, the Malian capital. He was holding court, proudly previewing rough mixes of recent recordings, including his collaboration with kora player Toumani Diabate—The Heart of the Moon, destined to win Toure his second Grammy Award—and also his own first album in over five years, Savane. Toure was beside himself with pride, discussing the music with passion as well as minute attention to the cultural significance of each song. The world knows Toure as an “African bluesman,” but he never embraced this idea. Rather, he set aside his noble heritage to take on the lower-status work of a musician, not to pursue rock ‘n’ roll dreams or transcend wretchedness, but because he wanted to educate people about the rich but neglected cultures of the Malian north, the Sonrai, Songoy, Peul, and Tuareg peoples. In one hauntingly melodious song from Savane, “Machengoidi,” Toure asks, “What is your contribution to the development of society?” and then answers, “I am a teacher.”

“When I think of my beginning in music,” he told me that day, “and when I hear it again, I sense a great improvement in the depth of my research and in the knowledge that I have. But that doesn't surprise me, because I grew up in this culture. I have evolved with it, practiced it, and I know it from A to Z. No matter what culture you talk about in Mali, when I play those songs, I have all the resources, the knowledge not only of its substance, but its biography, and its roots. It’s not every guitarist who has that.”

On Savane, Toure delivers an eloquent last word, playing and singing with unwavering conviction, and covering more stylistic ground in these 13 tracks than on any previous album. As Toure’s longtime producer Nick Gold said in a recent interview in New York, this was not a man who enjoyed making records. “Before this, you’d have to sort of persuade or cajole Ali into the studio,” he recalled. “Savane was a record he very much wanted to make.” The album was mostly recorded in two sessions, generally starting from raw tracks with Toure on guitar, and two musicians playing the spike lute known as ngoni or kurubu, one of them high-pitched and plinky, the other deep-toned and thrumming. “That was the core of the record,” recalled Gold, “the guitar and the two ngonis. Ali would start playing a riff, and just play and play and play until the other two locked in. It was very organic. He worked on the songs a lot, to finesse them and sculpt them. Then once he was ready to record, he banged ‘em down. Maybe two songs are the second take, but nearly everything is a first take.”

That freshness and immediacy comes through consistently whether on the stately, loping “Beta,” a spirit dance from Niger, the folksy, reggae-tinged “Savane,” or the hypnotic Peul celebration of the noble woman, “Penda Yoro.” Three ngoni players contribute here, including Mama Sissoko, a master of Malian traditional music, and Basekou Kouyate, a young innovator who has worked with the likes of Taj Mahal and Bela Fleck. Gold recruited overdubs from a Greek blues harmonica player, also Pee Wee Ellis on tenor saxophone, and percussionist Fain Duenãs of the group Radio Tarifa. These additions fatten the mix, notably on the opening track, “Erdi,” a majestic mega riff, dense with diverse instrumental voices vibing in unison. But it’s probably a good thing that Toure nixed further ornamentations from the final mix. They really aren’t needed and sometimes, particularly the harmonica with its distinctly American aura, detract.

Toure knew he was gravely ill in recent years, and that may explain his uncharacteristic burst of recording and performing. (Among other things, a collaborative Toure album with Toumani Diabate and Cuban bass player Cachaito Lopez awaits release in Gold’s vault.) But Savane will be remembered as Toure’s closing act. He described it as his “most traditional” album, but it is also his most adventurous in terms of exploring different rhythms, moods and sound textures. That might seem a paradox, but as Gold says, “For Ali, there’s infinite variety in traditional music. So maybe he’s saying, the more traditional it gets, the more variety is possible.” Toure described his late recordings to me as “the opportunity and the privilege to take one’s cultural destiny in hand.” His death, following on the heels of his second Grammy, triggered a period of national mourning in Mali, unprecedented for a northern musician there. Savane caps an extraordinary life and career spent uplifting overlooked desert cultures. With any luck, it may also help the world get over the facile “African blues” mythology, and see Toure for what he was: a man who gave ancient tradition so much fire and urgency that it couldn’t be ignored any longer.

Adapted from version originally published in the Boston Phoenix.