Blog September 21, 2016

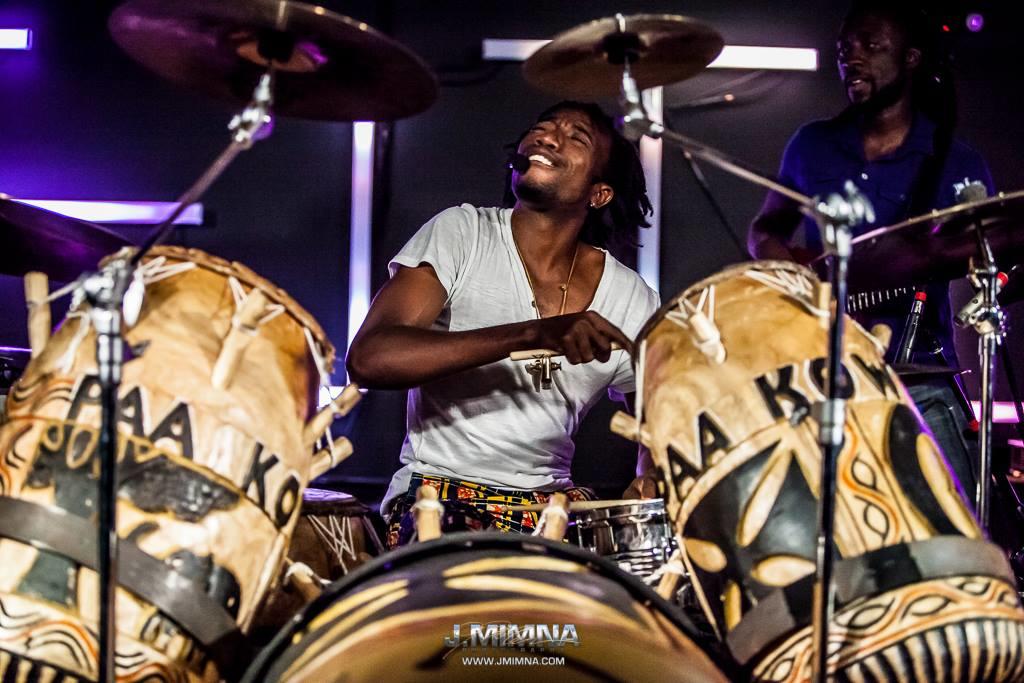

A Conversation with Paa Kow, Afro-Fusion Drum Maestro

Drummer Paa Kow (pronounced Pah-Ko) grew up in a musical family in a small town near the coast of Ghana. His artistic energy and creativity was clear from a very young age, when he joined his family’s traveling concert band playing drums. From there, his journey brought him to play for the biggest pop musicians in Accra and, in a twist of fate, onwards to Colorado, where he lives now, playing with his excellent band and helping instruct the Highlife Ensemble at University of Colorado .

He plays a deeply unique, technically demanding style of what he calls Afro-fusion, incorporating Ghanaian highlife with the international sounds of jazz and funk. Paa Kow’s drum chops are outstanding, laying down rock-solid, ornate beats, and occasionally bringing out a five-minute drum solo that you wish was twice as long. His innovation and passion puts him in a realm of his own, where people ranging from American jazz bassist Victor Wooten, jam band mandolin player Michael Kang, and Ghanaian highlife stars Amakye Dede and George Darko are calling for his talent. Be sure to keep up with PK’s show schedule: http://www.paakowmusic.com/shows. While his studio music is undoubtedly excellent, his live performance is really a remarkable thing.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dCLATH4Am54

Staff writer Sebastian Bouknight caught up with Paa Kow on Sept. 21 amid the bustle of midtown Manhattan for a long conversation:

Sebastian Bouknight: Can you introduce yourself?

Paa Kow: My name is Paa Kow. Usually they ask me, what’s your middle name, what’s your last name, but I started like that. Paa Kow means Thursday-born in my tradition. In Ghana, they name you after the day you're born. So that’s where I get the name Paa Kow. Everybody in the whole world knows me as Paa Kow. I’m from Ghana originally, you know. I grew up in a village called Enyan Denkyira, and at the age of maybe 14, I moved to Accra, I start playing with all them big guys in Accra.

Yeah, so tell me a bit more about your beginnings. How did you start playing music, how did you end up in Accra, playing with them?

It’s interesting. I start playing music the age of 5, that’s what I think. Or maybe I started even before then but I don't know! My mom is a musician; she played with some bands in the hometown. My uncle got a chance to get equipment from a guy who lives in Germany, so he started a band. It’s a concert band. They've been playing around and I get inspired from them, from my mom and uncle. And I start making my own drums out of cans and stuff, anything that it can sound good for me to bang on it. I start making my own band in my mom's house. Everybody went, Hey hey hey! because I bring friends and make a mess cause I have to set up and do my concert and all that. My uncle's concert band started really playing when I was grown up, the age of like 6, 7, I fall in love with it…so I said, Man, I love this. And I started playing percussion, which is you know, making my own drums. I didn't have much strength to play with them…

Because you were too young?

I was too young! I could not even kick the bass drum, I was too young. But they were like, Hey, Paa Kow can play! So, there's a gig, they were playing a gig in my hometown and I say I feel like I want to play congas, so they put me on the chair at the congas because I could not reach, and I started playing, and everybody's happy, like he can play good, and put money on my forehead. And I was like, Wow man! This is good! Playing music, people can give you money and all that excitement. I want to do it! So, I start playing congas. They know that I can play congas, but then, one day they were rehearsing and I went there after school and I said, I can play. So they gave me a tune to play and I played drums. That was what made me a professional drummer.

Now, it become like something like, oh, the band leader's nephew, he can play drums and he's really young and we want the fans to go crazy. So it kept going and going and I start playing a lot of songs by the age of 10. Soon the drummer was gone, so I take over. We went on tour [for] like three months, just me playing drums. [In] a concert band, man, you play for long time. Like we played from 8 o'clock to 11 o'clock singing highlife music, and after they start a concert. So after I have to play the staging drums. They're doing a concert, they have to act. During the act they have a comedian come. Overtime they raise their hand, you have to put a hit there–BAM.

Ah, so it's like a full-spectrum kind of performance, like a musical variety show almost?

Yeah, it’s serious! And I think that makes me who I am, it makes me a good drummer, because when the comedian raise their hand, he wants you to hit with him, and that stuff makes me be a smart drummer.

Because you have to pay attention.

Yeah, pay attention, bam bam, like that. So that’s what makes me a better drummer. I don't call myself [the best] drummer because I think there's a lot a lot to learn, being a musician. Like education, you never have an end. But it makes me who I am now, that at least I can stand in front of thousands of people and perform for them and for them to know that I have something good in me. That’s where I started. When time goes on, I realize, to play drums in Ghana…now I have to play in a dance band.

So the concert band--is that highlife?

It's highlife and they do staging, acting.

And a dance band?

All highlife, no staging. And the concert band they go from village to village to village. They show up in the village, they turn on the generator and that’s all the lights in the town, and everybody gets excited. It was good man! Like you play every night, except when the van broke down. And we have to get stuck somewhere in the village for two weeks. My uncle has to travel from there to Accra to get a part, has to drive there, and we get stuck for two weeks. But that’s what makes me who I am. I feel like I can go everywhere. I can tour all over the world, everywhere, even if you get there and there’s no place to stay, I made it happen.

You're adaptable.

Yes, yes, you know. So, it makes me strong. Everybody started hitting up me: Oh, Paa Kow, Paa Kow, youngest drummer in Ghana. And then I leave my uncle's band, and I go play with [another concert band] for a few months. And I was in school that time, so like, [during] school vacation I do it, but it got to a point when I was like, Oh, music is taking away from the school. But I love the music! I finish middle school…and I say man, I love music and I want to follow my dream. I could spend all the energy for school and not be here right now. I love the music I want to do it. So then I left that band and everyone wants to play with me!

There's a guy in Accra, his name is Abrantie Amakye Dede, he's one of the biggest highlife artists in Accra. And he, Amakye Dede, took me from my family--the way he took me was great, 'cause…I heard that he traveled to the U.K. and some of his musicians didn't return back to Ghana so I was like, Oh, I wish I get that chance to go play with him! So somebody took me [to Dede] and said, This small boy, he can play. At first he didn't believe it, and said go home and come back. Friday night they were performing in this club, and I show up and I was saying, Hey I’m the one, I can play. And he was like, really? You have skinny legs! You couldn't play! [Laughs] He was shocked…I know the reason why he was shocked, 'cause I was young and skinny. So he was like, What songs of mine can you play? You know my tunes? And I was like, Yeah, I can play this, I can play this. The show start, and they say, This boy, he can play, and the whole room went "Wow!"

And from there, it changes my life. I become a really big musician, professional musician in Accra, touring with all those famous musicians. And I play with [Dede] from like, 14, 15 to like, 18. Then I left and everybody wants to play with me. So I went to play with Megastar Band, Western Diamond Band… you know, doing my thing, living the dream with the music. It’s not easy to just go get a chance to travel abroad, being even a band manager or somebody, but being a musician was good, and they see my talent and they all travel with me, everywhere.

So when you were young, at that time, you were thinking about going to the U.S. or the U.K., to live there or just to visit?

Sometimes you know, you look up in the sky and see an airplane and wonder where it is going. I didn't think about moving here, but I see an airplane and say, Where is this plane going? I wish I could be able to know where the airplane is going. So like a little kid in my hometown, we see the airplane in the sky with the lights—that’s part of the dream. But I moved to Accra, I was set enough that I’m a successful musician because everybody wants to play with me, they tour with me, give me the foreign money, it’s worth it, you know. I play with some of the churches too. But some of my dreams, I dream that I am somewhere and I see foreigners, you know. I mean I dream about it, but I didn't know that’s what it would be like.

So how did you end up in Colorado?

So I end up in Colorado—my manager Peyton, he was visiting Ghana as a student with a professor who lived in Denver, his name's Kwasi Ampene. He brought students from C.U. [University of Colorado] to Ghana because he had a program he called Highlife Ensemble, [where] they teach drumming and dancing and highlife music…He actually saw me playing with one of the biggest musician in Ghana at the national theater—Kojo Antwi—a reggae artist, pop star…and thought oh, this guy's good! So he brought the students in Ghana, and Peyton said, "Oh I’m looking for the best drummer in Ghana," and everybody say, "Oh, Paa Kow, Paa Kow." And he got my number and he called me…so we met up somewhere, and he said, "Wow, man, the talent you have! You need to come to America. I think America will appreciate you a lot, because I’m a drummer myself, and the things you do—man, its crazy."

So he brought you to C.U.?

Yeah, so he studied with me and all that and…so they talked to me with a professor and he said, "Hey, Paa Kow's great, I would love him to come to C.U. and teach and teach you more." So they invited me to be a part of [their annual concert] and teach, so I was a guest artist in 2007. They brought my here and I started a band—my dream band. I found a couple of guys in the C.U. music school and, man, they can play. But the time comes and I have to go back to Ghana. They were all sad; Man, Paa Kow had to go back to Ghana…because they love what I brought. Let’s bring Paa Kow back! So the bass player wrote me a letter to come back here to keep doing what I’m doing…so I keep going back and forth, back and forth, and I decided to stay, in Memphis, where Peyton was a percussion player. We had a [band with a] bass player and trumpet player in Memphis, but it didn't work out. I want to have my highlife fusion, and I feel like I didn’t get what I need to do my band, because its just bass, conga drums, trumpets…

So you wanted a bigger band?

I wanted a bigger band. I was like, man, this is not working. They know that it was hard for them, because they know that I’m looking for something I don't get. So we're like O.K., lets break up. You go do your thing. Peyton drove me to Colorado, I start my band there, I get out, find musician from the school, people that know their instruments, and start showing them the language that I want to speak. It’s been a journey, but that’s the way I end up in Colorado.

That’s a long, long journey, man.

Yeah, I have to be here for a couple more years before I become a citizen. And you know, I’ve been here a long time, not seeing my family, my mom. But you know, I been doing that in Ghana, I’ve been touring for months, so she's used to that, you know? So she has the patience for me… So the band was going well, musicians come and go, the people I start with, they are not the same. I’m also a bass player myself…That's the way I write my music.

So when you write music, you’re thinking in drums and bass?

Yeah…so when I’m writing music, I get my bass part first, and I write a conga part that will make sense with the bass part, to have a good conversation. But me, being a drum set player, I know what I’m going to play when I write the bass part. So I get a strong foundation—congas, good percussion, good bass part and drum set, and then I start putting all the melodies on top of it. Usually I get the bass part [first], so I write the melody part [while] doing the bass.

So the melody comes out of the bass.

Yeah, I mean I don't share that with people, but I feel like every musician—drum player, percussion player—you have to know how to play electric bass, keys, etc. So I play every instrument, man, I play keys, bass, all that.

Some of your music is sung in English and some of it is in Fante and sounds very like highlife style. What decides what the sound and language of the vocals are?

My goal is [that] I want to have everybody's taste. That’s why my new album is going to be called Cookpot, you know? 'Cause I have like, all the ingredients—you need tomatoes, peppers, onions to fuse together so when you actually give it to somebody to taste it, they find something, you know? So that’s the way I thought about my music. And I don't want…get stuck with the highlife music. It’s going to be boring! ‘Cause highlife music its all singing, and guitar, you know? Which is cool! But, if you’re singing about something people don't understand, it’s hard for them to listen to. Which is O.K., because…you actually don't have to understand to hear what is going on. But, I want to be heard all over the world. So if I find a way to speak English, then I can at least write lyrics that can be heard.

So it’s kind of about accessibility?

Yeah, and I want to create my own thing that’s not based on highlife, its not based on jazz, its not based on Latin music or blues, but I want to create my own thing…They say Michael Jackson is the king of pop--I want to be the king of my creation.

What do you call your creation?

I call it Afro-fusion. It means pop, jazz, or whatever, blues, or whatever.

Cool. What are the ingredients of your cookpot? What influences do you bring into your music?

I feel like the new Cookpot, its totally different album from [my two other albums]…but always want to just create, because when I’m growing, the music… it takes life! You get smarter when you're growing. So I feel like with Cookpot—I feel like I get to a point that the idea is more jazzy, I get my influence from Ghana, the traditional stuff, and I have fusion. I still have some singing, and some instrumental.

This is all from the new album?

Yeah, I started already, and then [went on] the tour, and I have to go back and do all of my checks and all that.

So who are you listening to right now? Who did you listen to today?

It's hard to go for a day and not listen to music, but sometime you need it to just think of yourself, if you have like a show coming up and things like that. I like to listen to Jaco Pastorius. He's a really, really good musician. I know he started playing drums before bass, ‘cause when I listen to his groove, it touches my heart, because I can tell he is a drum set player…The bass part he wrote matches the drum part. When I listen to his music, I’m like, Oh that’s me! I listen to Weather Report a lot. Joe Zawinul, all those guys who put that Weather Report music together. Amazing man. They get me inspired. And I like Buddy Rich—Buddy Rich is a great drummer–great energy! The way he hits the drum…That’s what I do, you got to know how to hit. You're not going to hit it hard [enough] to break the head, but you just bounce so people can see that you're playing with your heart. Today, I listened to Jaco.

Peyton was saying that you also like Richard Bona.

I like Richard Bona. Richard Bona is a good player… we both kind of have different backgrounds, but I like him ‘cause he's a bass player and I like the way he plays. Richard Bona is a really, really good player.

It’s cool that you're playing at his club [Club Bonafide].

Yeah, I wish he could be around to just figure out what I’m doing. But I mean, he's from Cameroon and I’m from Ghana. Its all West Africa, but its different backgrounds, our music is totally different from Cameroon. But I like him because he was smart enough to not get stuck with the traditional stuff. I mean he's still playing the traditional stuff but also being part of the jazz scene, he can play with all those guys, Joe Zawinul…

How about George Benson?

Man, I love George Benson! I love George Benson. Even from Ghana, back, I love George Benson. Chick Corea too!

What did you listen to growing up, as a kid?

Highlife music, all those guys, you know…I grow up listening to Dave Walker, one of the best drummers in the states, a white guy. Dave Walker inspired me. Earth Wind and Fire, back in Ghana. And when it comes to jazz, George Benson, Chick Corea…I grow up listening to those guys. Before I come to America, I hear these guys, Charlie Parker, Buddy Rich, Steve Smith, all those guys.

Did you get into to any of the more Afrobeat side of highlife, like Ebo Taylor or Gyedu Blay Ambolley?

Yeah!! Ambolley! I grew up with his music. Ebo Taylor is a little old, he's old. I’m 33 now, I was born in '83, so I was growing up with like Nat Brew, Ambolley, Pat Thomas, George Darko, all those musicians. And I ended up playing with them! So, I grow up with those musicians. But, I still hear all the highlife music, I didn’t know who is Ebo Taylor, but now…I can [hear him and] figure it out, like, Oh that was Ebo Taylor! But I grow up with all those guys.

I was watching one of your videos, “Realize,” I think, that sounded very much like Afrobeat.

Yeah, like Fela Kuti?

Yeah, like Fela.

Yeah, “Realize.” Everybody knows that song. I play a gig, and people are like “Realize,” “Realize,” you know? But I find a way that it sounds like Afrobeat, but when you listen to the bass part, its jazzy, you know?

Interesting. Before, you were saying you didn't want to get stuck in the traditional stuff. Do you feel like musicians that play more traditional music are stuck in something?

Well, there's a lot out there, boss, when it comes to music, a lot to research. So, it’s good to be like, Oh, this is the tradition. You're born with it, you have it. But you have to give yourself a chance if you want to leave to the States or the whole world. You have to be open to work with everything that's going on in the world. I’m not thinking they get stuck, but I know a lot of highlife musicians that they don't even get heard in America. Because the highlife musicians they don't even write their own songs, they all play “pon-sa-pon-sa-pon-sa”…in Accra, you know? And [across] the ocean, you don't hear them here!

It’s a great music, but you can hear it’s all now going to hiplife. And hiplife—its not like I hate it, I can’t say I hate it, but the hiplife music, the way they try to learn, like, somebody they taking like American pop…it sounds really weird. It’s a good thing, but Americans cannot pay attention. They want something unique! They want something like a highlife. You see? Its good to go to Ghana to find a musician that plays straight-ahead highlife. But me, I want to go all over the world. I learn so much that I love jazz music. But I want to just fuse it—that’s why I want to call it Afro-fusion, so I don't get stuck with just highlife…It’s not boring, but if I want to stick out, I want to have people's favorite, people's taste for my music, I want to create my own thing.

That’s interesting what you said about hiplife. I feel like the guys doing hiplife—Reggie Rockstone, Sarkodie…

Yeah, yeah! Sarkodie! Oh, you have been in Ghana before?

[Laughs] No…I just like the music.

[Laughs] Cool, cool, cool.

But Sarkodie was in Harlem last year—so he's going all over the world with his type of fusion, a different type of fusion.

Yeah, it’s a different type of fusion. But…jazz people are not going to pay attention to that. Sarkodie, he doesn't come to America to play in a jazz venue or perform in front of the American [populace], he just come to play for Ghana [populace], and that’s all they know, they come and play here at some church…

He played at the Apollo!

Which is cool, a unique experience. Maybe [he’s attaching himself with] American pop musicians so he can get somewhere. But I’m not offended with them, 'cause I know that it’s different music, they way they're doing [things], putting some [Auto-Tune] on their voice, and its all programming music. They don't do the live performance, they come and mime with no musicians, no live performance. So there's no soul in it. I like the music—it’s different. But me, I’m a jazz musician, and that’s what [George] Darko will tell you, that’s what Victor Wooten will tell you – I’ve played with Victor Wooten before—all those heavy musicians, they have the talent…I do what I do, instead of trying to copy somebody…my talent is what I have, you cannot take it from me. But I feel like hiplife, they are taking the foreign pop and attach what they do.

I feel like that’s kind of happening everywhere.

Yeah, and they're bringing all the highlife music down in Ghana! It’s a big, big problem! Because now, all the highlife musicians are struggling, you know? Because the youngest are brainwashed with this pop…its not a bad thing, its a good thing, but I wish they could still allow the highlife music and the performance of music to keep going instead of miming. Take one mic and one person to come stand there with the DJ, and the real musicians are struggling, you know. I’m not against it, its just too much now, and me, I’m a jazz musician, I wrote my own stuff…

At this point the space we were in closed, so we moved across the street to an outdoor plaza. We start talking about Club Bonafide, where he is scheduled to play the next night.

Yeah, it’s an interesting venue, very intimate.

Yeah! When we get a small, small venue like that, you know, its good to know how to play quiet when you are a jazz band, and its good to know how to play loud when you [have a big crowd] and they need the energy. So, I can play everywhere, I can play in every venue. And that’s why I start playing these shows, because if I can get somewhere that I know is small, we need to just get really jazzy, quiet, you know? I’ve been to Bonafide, I went there to check it out, I saw the way the room is. Last time I was there, it was like a seven-piece band on stage, with a piano, two horns sections, percussion.

Wow, must have been a tight fit.

Yeah, I think we will fit.

So, going back to what we were just talking about, about hiplife and Ghana. How is your music received back home?

The youngest like it. The oldest, when they hear my music they're shocked. Wow! Who this Paa Kow? This young guy, wow! You know, they get excitement like, Wow, even a young guy can write these songs, and not what everybody's doing now. So they go, Wow, this reminds me of Osibisa… This is what the old people want to listen to now… they find something that I’m bringing up with my own fusion and the traditional stuff. So everybody likes it, when I go to Ghana now, everybody's like, Paa Kow's here!

Do you think it took going to the U.S. to gain that popularity?

Yeah, I mean, I was popular, being a younger drummer in Ghana, that’s the way I get my name, but I come to America and didn't stop doing what I’m doing. I keep going and now, [with] Facebook and everything, they see what I’m doing and they bump it up really, really large. [Now] every time…I want to go to Ghana, I even feel like, Oh, I’m going to be going everywhere. You know…everybody wants to listen to good music! I think that's what it is. It’s not like people don't like to listen to good music, but if they get stuck with one thing for a long time because they think, Oh, marketing-wise, rap music [is the best], now let's do that. Sarkodie does that, it’s going well, Samini did it, it’s going well. Shatta Wale, you know? He's one of the biggest in hiplife, he calls his music dancehall. Yeah, and they start singing like Jamaican patois and all that stuff, but I feel like there’s something deep to us too, our Ghanaian music that those kids are not doing.

Like they're looking elsewhere?

Yeah, I feel like…everybody’s growing up, being a musician, getting that opportunity. Back in the days, even though at that time was Burger-highlife, everything from George Darko…Yo, I was band leader in George Darko's band, and George Darko, he lives in like Germany, but he always call me like, Paa Kow, put the band together, call people who you think you can play, learn the song, I’ll come and play the show, I’ll be in Ghana for a couple months. So…I was his leader for a while. George Darko's a jazz musician—listen to his music, you get all those bridges, you know? And he loves George Benson. So we'll play “Mr. Magic,” “Take Five,” all those jazz tunes…So, people like that, putting that music out there as a Burger-highlife, was a really, really good time, you have the synthesizer, everything. Its solid!

But I feel like that thing is losing right now, because, man, it’s like every music in Ghana is radaradarada, you can’t even hear the guitar. Where is the highlife forever? Where is the tradition forever? Everything you hear is like American style, put that [Auto-Tune] on your voice, so if you're not a singer you can sing. But it's not like that, you have to show your natural voice. That’s what African music is based on. If you hear like, Youssou N'dour…Salif Keita is one of the best singers in the world. Yeah, man, heavy! So, what the kids are doing [is] because of the money. I’ve been told…that if you're trying to make a living playing music, you're not going to get there. It has to be [your] heart. This is my passion, this is my career. Its not like, Oh, I’m just trying to go work at the grocery store a little bit and somebody call me for a session, I got to go, this guy call me for this, I’ve got to go…You have to focus. So, sometimes, I question myself if I see people trying to break through in that condition cause they think, Oh, being a musician is great! ‘I saw Sarkodie with a nice car, and me too, I think I can rap a little bit’ and they go into the studio and then what they do is like samples, which is…you know? O.K., what’s your lyrics [then] they put [them on the beat] and that’s it. They don't write the music!

I feel both ways about it—I feel like there is maybe not as much unique compositional creativity in international pop music, but then I also think it’s great music.

If you see like, Herbie Hancock, he's still playing, playing at all those good jazz venues! Imagine someone like that, he's been doing it and he'll be doing it till God calls him. But that other stuff, it doesn't really last. Trust me, last year I go to Ghana, there's songs there, and if I go back again, where’s that song? Its not there, it’s gone. And they only release one track. Where’s the act, where’s the everything? One track that’s it, no nothing [gestures at a CD]. This year when I go, something new will be there. But I feel like the deep stuff will be there forever. Like Fela Kuti! James Brown. All those musicians, you know? They focus their dreams to do what they are, instead of trying to copy someone, and it doesn't stay. Overtime, I go, I hear new hiplife, three months go by, it’s gone. Osibisa stay now. People like listening to Osibisa.

So who else do you think is making that kind of stuff you're talking about?

I think I inspired a lot of musicians in Ghana now, all the young musicians now, they're like, Oh, Paa Kow, he's killing it! I inspired a lot of musicians there, but since I don't live there, I haven't heard the guys perform and play my songs. Most of the musicians…they get stuck on the hiplife musicians, ‘cause its really tough to get a band together and write their own stuff. But I hope I inspired them enough so that they all realize to live in the music, instead of being like, Oh I need the money, let me go play with this guy. ‘Cause then you become a musician prostitute! 'Cause you need the money, got to play with Sarkodie, got to play with Tinny. So, I hope that I inspired them enough, but for me now, what I’m doing is more pure, like I go to the studio and play live. Everything you hear on my album is recorded, I don't program anything. I just want to hear that from them. I mean programming and stuff, its cool, its cool, [they’re] good tools, but if you want to do your traditional stuff, then you need to write, you need to play live, so people, musicians can be able to get work and perform in front of people…It makes the soul happy, it makes people happy. When I hear the hiplife, I’m like, Ah, it’s fine, it’s one groove, it’s fine, so I don't pay as much attention. Nothing wrong with the music, but my focus is different, I’m trying to do my thing.

Speaking of doing your own thing, when I saw you perform, I was really struck by your drum set [which is made out of traditional atumpan and fontomfrom drums]—The coolest thing I’ve ever seen. Tell me about that, how did that come to be?

You know, I told you from the beginning I’ve as always been in my own things, even when I was like 5 years old, making my own drums from cans and strings… I used those strings and the fertilizer sack, the rubber ones, and [demonstrates attaching the rubber sack as a drum head]…So I have had that idea since being a young [kid]. So I come to America and I play this Eco-X drum set from DW – it’s a great, great set, made out of bamboo. I like it! But I was like, man, I love my African stuff, I love the atumpan, the fontomfrom, but I cannot get it in a drum set. I told Peyton, I want to make my own drum set…I want a deep, long fontomfrom, like a 22 [inch] as a normal bass drum, I want to get my first tom like 10 [inches] like a normal tom, the next one 12 [inches] like normal tom, and the floor tom like 14 [inches] like a normal tom…He said, Yeah, O.K. let’s go to Ghana, I’m going to put in an order.

Kofi Ghanaba has a drum set like that…but he plays more traditional, he doesn't play the way I do. I want to bang my own drums, 'cause the sound I need…don't get me wrong, I like the regular set—anything I get I’ll make good sound out of it. It could be a can, [and] I’ll still perform right now. With this, I’ll be able to play my songs. So, I go and I tell these guys, I want to get a drum set out of an atumpan. They said "The bass drum will be too big, how are we going to find the wood?" We give them the money…[and after a while,] they're like, We got a tree for the toms, now we're finished with the toms. I’m like, Where's my bass drum? They're like, We can’t find the wood for that. Dude! Are you kidding me? I know this is Africa, we're going to find that thing. It's African teak, the wood. And then my time was getting close to fly back and they were like, Hey Paa Kow, we find the wood, congratulations. I went and they were like, Everything is solid.

And that’s the way…that’s me taking Ghana to the top. I don't want my country to be bad music-wise. They did it for me, everything is ready to go, and I bring it to America. I found a guy…who works with metal…So he built a stand so the bass drum can lean on it really nice. And then we need to make the pedal so it can reach the drum…because I want to play it so I can still get that attack, like playing a normal drum kit. I want to make it funky, you know? So we get it and I paint it on my own…I’m an artist, you know, I paint a lot, ‘cause it’s like a music style.

Cool!

Yeah and it works out! It sounds so good…and that’s going to be something that I created. I’ve had that idea since I was a little kid, you know? It fit in with my sound. Its crazy, if you hit the bass drum…on my kit, its really good but it gives me some vibrations of natural sound. But if I play now on my [DW] kit, it looks small in my face. It’s a really good thing, that normal kit has great sound, 'cause there's a lot of science into that to make it sound good, but I love my [custom] drum ‘cause it’s my dream. Not just that it makes me stick out, ‘cause nobody has that drum set…it helps my performance, it's a different act…and the sound, I love the sound so much. Sometimes when I play, if I want the sound chunkier, I use [traditional curved drumsticks]…it's working good for me.

Cool. At C.U. you teach students, right? What do you teach them? Do you teach them your style of Afro-fusion?

Well, this year they had me being a guest artist for the Jazz Academy, it’s a camp. And I teach them how I put rhythms together, my own stuff…How to be a separate musician…swing stuff, cause I’m into swing too. When I’m teaching the Highlife Ensemble, they pick up my song, and I'll take my bass and try to teach them: this is the bass part, you play this, you play this, the same way I do with my band. But now I’m busy, I don't teach as much anymore, unless they need my help. Still when they have a big show coming up and they request me and I go in and if I have time and teach for maybe a month…if I go, I teach highlife music.

Do you ever find that you need to teach more traditional rhythms, with atumpan and fontomfrom?

I don't really teach that stuff. There's a traditional musician for that, that’s all they do. They use the drum to talk…but I’m not too traditional. So I don't teach those things, I just teach highlife music, what it’s based on, clave, how the clave fits in highlife music, how the clave fits in Asante music. But I don't teach really stuff on the atumpan.

Cool. I ask because sometimes I hear fills or solos in your music, or sometimes even horn parts, that sound kind of like an atumpan talking.

Yeah, it sounds like that, yeah. I grew up with those sounds, so, I do it in my playing. I do it anyway, even though I don't know what I’m saying. Sometimes I know what I’m saying, and I can say it—I love music so much that I wish that I can see it, you know? But that’s the way God created it. But anything that comes to you that you want to say when you're performing, you say it. Like I can say anything out of my language, speaking Fante. I say my language, I bring it out, play my drums, you know? And before, you see [that] I play some crazy stuff, like, what is that, you know? ‘Cause I speak to me, myself and I bring it out. But in the traditional stuff, they have [the same idea], but they have [certain things] that they have to play. But mine, I can play everything…you just bang on the drums and make a beautiful sound out of it. That’s how I feel.

Often your lyrics are kind of about feeling good, love and mutual support. What makes you feel like that's a message you need to give to the world? Where do those lyrics come from?

I don't think so hard to write the lyrics, ‘cause when that happens, I feel like I’m struggling for the lyrics to come out. I like when the lyrics come out naturally. All those lyrics come to me naturally. Sometimes people ask me, Are you into politics and stuff, cause I love [the song] "Realize" so much. And after the show I get somebody saying, Let’s start a revolution! “Realize!” you know? And I’m like, I’m not a politician, I just see what’s going on out there in the world, and you know, from Africa like that. People in the States always see what is put on the TV, and they believe it, but it’s not like that! It’s not like, if you go to Africa, you see lions and things everywhere, in Accra! So, I see what is going on out there, and what my heart is telling me to say, but I’m not into politics or anything. My music is just real, how it comes to me.

How do you hope your music makes people feel?

I think that it makes people feel good. ‘Cause when you say the truth, people that are out there—they have open ears, they hear and are like, Wow! This guy's saying a good thing. But I’m not pointing a finger to anyone. We are all human beings and we all need freedom. [I do have songs like] "Realize" or "Black and White,” but most are like love songs, and about [how] we have to communicate and help one another. We all always need each other. So I write about things like that, but not trying to be political.

Not like Fela.

No, no, Fela, he wanted to be a leader of a country. Me, I’m not trying to be a Ghana president, an American president. I just want to be a musician, what God gave to me. I don't want to get any attention for the things I’m saying or be a leader of a country. I always want to write peaceful things for people to listen to. And people think it’s a positive thing, instead of trying to be a leader, a president. I think it makes people feel happy, feel good.

So it’s about the music moving people.

Yeah, yeah, even the ones that don't have lyrics, you can listen and be like, Ahh yeah.

What would you describe as the most rewarding part of your life as a musician? What has it given you?

It’s given me happiness. I’m the most happiest guy, you know. When I hear music, I smile, you know? I feel like I’m a free man when I hear music play. The music I do gives me the freedom to go everywhere, you know? People accept me here because I’m a musician. It’s easy for me to get places. Now I get to talk to you for what I’m doing. So it gives me opportunity to go all over the world to communicate with people, human beings, as me. That’s what I’m happy about. It’s not easy to go travel, but having music–it’s a key, it’s a visa, it’s a green card, it’s a passport to get everywhere to just do what you want to do. And that’s what I feel. I’m a happy person.

Where's your favorite place that you’ve been to?

It’s hard because we all belong to this earth. Ghana is the same land as here, and America is the same land as Ghana. I just love Earth! Everywhere [where] there's Earth, I like it! I don't think I have my favorite place to be, ‘cause it's a one creation. Same as the sky, it goes and goes. The Earth is one. So I feel like everywhere I'll be, I deserve there. My favorite place is the Earth. [Laughs]

[Laughs] Beautiful. Thank you so much for talking with me.

Thank you so much for having me here and having a conversation about the music, I appreciate it!