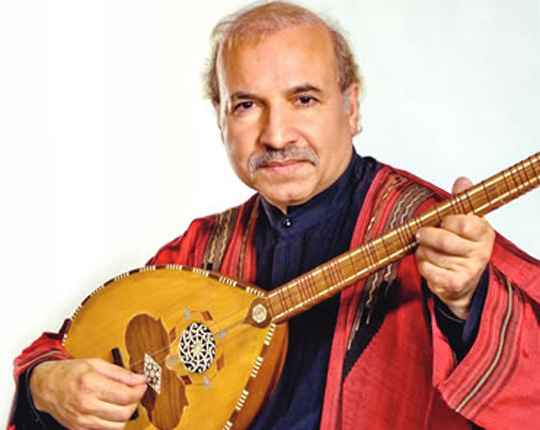

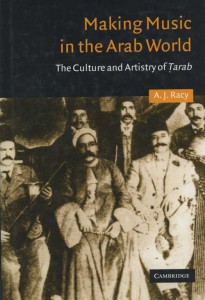

A.J. Racy is a professor of ethnomusicology at UCLA, and a distinguished performer and composer. He is the author of “Making Music in the Arab World: The Culture and Artistry of Tarab” (Cambridge University Press, 2003). He is also, in many ways, the spiritual and intellectual father of Afropop Worldwide’s Hip Deep series. The pilot for the series was the program he helped us make: “Tarab: The Art of Ecstasy in Arab Music.” He has advised us on our Al-Andalus program series, and more recently, our 2011 series on Egypt, and our 2013 series on Lebanon. This is the second part of Banning Eyre’s 2013 interview with Professor Racy. It concerns the Lebanese diaspora in the United States and, especially, Brazil.

B.E.: You talked about the fact that there is this incredible history of diasporic movement out of Lebanon and Syria in the decades before World War I. Let’s talk about the historic reasons for that.

A.J.R.: There are many reasons why so many people moved from Lebanon and Syria to places like Brazil during the late 19th century and, especially, World War I. People cite the economic need, the collapse of the silk industry—a local, homegrown industry—and also the famines that took place, the Ottoman oppression at the time. Also Brazil opened its arms to immigrants from that part of the world, officially and informally. Brazil was a suitable place to go and establish yourself. There might be other reasons as well. But what’s important is that people who did go to Brazil from these areas, many of whom were from rural areas—villages and larger towns in Lebanon—established a renaissance, a cultural revival that was really almost unrivaled in the history of Arab literature.

They established journals in Arabic. In the 1920s, one of my uncles, Sami Racy, in São Paulo, established a journal and I saw about twenty volumes, very thick volumes, all in Arabic. There was poetry by famous Lebanese poets in diaspora and some articles in Portuguese. But these journals also talked about the latest in science, up to the late 20s. The volumes I saw also gave me information about the musical life of people there. Each of these issues had news about cultural events. You can see that Arab singers and musicians came and performed. Sometimes, there were musical performances in the Brazilian idiom, songs from Brazil as well as Arab songs. One illustrious immigrant culturally, musically, and artistically, was Najib Hankash.

B.E.: Tell us about him.

A.J.R.: Najib Hankash is very well-known to the Lebanese and in the diaspora community of Brazil. He was sort of like superstar—a delightful person, very funny. He had a beautiful voice, and he was highly visible. At many events, Najib Hankash was there. He was born in 1904 in a town called Zahla or Zahle in northern Lebanon. He went to Brazil in 1922, and in the 1920s and 30s he was very active. He sang some songs on local record labels, and they were popular, not just in the community in Brazil. I have noticed that some immigrants from Lebanon and Syria at the time, the 1930s and 40s, had access to his recordings.

Hankash performed parody songs; one of them is “The Story of the Peddler.” It is

about a Lebanese immigrant who goes to Brazil, works as a peddler, and eventually becomes very rich, a nouveau riche. He wants to marry a beautiful young woman, but he becomes too “choosy.” As he gets older, he tries to look younger and buys a fancy car. Then he finds a beautiful young woman who, alas, spends all his money and makes him poor again. So we begin to see that the concerns are localized to the circumstances of the immigrants’ lives. Hankash concentrates on the experiences of the mahjar, the place of immigration.

B.E.: So Hankash is basically a teenager, eighteen years old when he comes to Brazil. And he lives there for decades observing the pattern of these Lebanese people coming newly to Brazil and even poking fun at them. At the same time, he’s sort of mythologizing their experiences, right? And he is able to do that because he has this dual perspective.

A.J.R.: Yes, he understood the culture of Brazil, the immigrant culture. He also had a keen sense of humor to make light of it sometimes and had to sing in musical and literary styles that appealed to the community. Now he probably watched people come in, and he also watched people that had been there before and he saw what happened to them. “The Riches Without Culture” is one song he recorded in Lebanon after he went back. But I’d like to talk about what he did with a poem by Gibran Khalil Gibran.

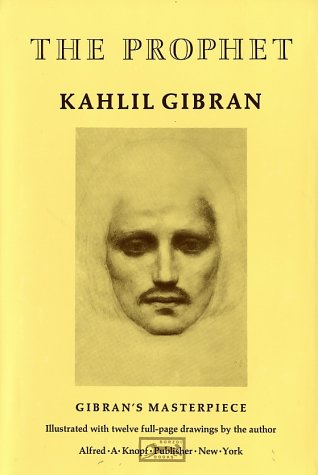

B.E.: Good. Why don’t you start with a brief introduction to Gibran. Most people know him, but some may not.

A.J.R.: Right, right. Gibran is really a remarkable figure internationally. He’s not just a poet who came from Lebanon and settled in America and wrote some books. Gibran was born in 1883, died in 1931. He was born in an idyllic town in north Lebanon called Bsharri. He came to this country and, I think, from 1912 on, he became a citizen in New York State. He acquired the residency there, and he really bloomed as a philosophic writer and poet.

He was influenced by figures like William Blake, Nietzsche, and others. He wrote in Arabic and in English. I read Gibran in Arabic when I was in school in Lebanon. He is known for giving a new, fresh breath of imagination and artistry into Arabic language writing. He moved away from the more traditional style that maintained certain expressions and themes. One of the books, of course, that he wrote in English was The Prophet. The Prophet sold more than 20 million copies. People in weddings in this country often read a passage from it. The book is also quoted on many other occasions. People find things in The Prophet that apply so poignantly to their own experiences.

B.E.: I know this. When I was a kid in the early 70s, everyone was reading The Prophet. I even used a quote from it in my high school yearbook entry.

A.J.R.: Fantastic. Now, in another of his books, Gibran wrote a poem about the reed flute, called the nay. The reed flute is a very important instrument in Middle Eastern cultures in general, particularly in the Sufi tradition. Jalaluddin Rumi, of course, wrote a famous poem about the reed flute and its sound being akin to moaning, remembering; the instrument cries to go back to the reed garden from where it came. In this case, the notion of yearning or reuniting with the Divine has mystical connotations. Gibran’s poem is a little different. It gives the sound of the reed flute a kind of eternal quality, and the poetry says something like, “Give me the nay and sing, for the sound of this nay lasts beyond eternity. Its moaning remains after time ends.”

A.J. Racy and nay (Eyre)

As a nay player myself, I identify with both poems, by both Gibran and Rumi, and I recorded a nay piece, “Ecstasy,” with the famous Kronos Quartet for their CD Caravan in 2000. Gibran appealed so much to many Lebanese in the diaspora because he epitomized success, imagination, and the traversing of physical distances and cultural barriers. For the immigrants, the identification with Gibran meant so much. Many Brazilians wrote about the trials of immigration. It was very hard to come and suffer and build yourself. The word they use is “saga.” “Saga” comes up so often in the immigrants’ writings. And if somebody becomes so distinguished, a person like Gibran, that person becomes a role model, because his success is a story you would be proud of.

Najib Hankash

Now, Najib Hankash took the lines from that poem and set them to a melody that he composed. Interestingly enough, a part of the tune has a hint of a tango, “La Cumparsita.” He worked with an orchestrator and composer in Brazil named Gabriel Migliori. Hankash’s song, “A‘tini al-Naya wa Ghanni,” was recorded on a 78 RPM disc in Brazil. The company that recorded it was Continental. In Rio de Janeiro, Professor Paulo Gabriel Hilu Rocha Pinto gave me an original disc of the song, and I analyzed it. Hankash sang in it, and the music was absolutely beautiful.

Years after, in 1947, Hankash returned to Lebanon. He went to Brazil briefly after that, but returned again to Lebanon. He spent the rest of his life in Lebanon, where he was acclaimed as a superstar comedian. He brought his songs with him and recorded them again with his voice and with a modern-sounding orchestra, in the Rahbani style. His recordings were very well done. He recorded “The Story of the Peddler” and recorded another song with lyrics by a well-known Lebanese immigrant poet. That one has very nostalgic lyrics. It said something like: “When will we go back to you, oh Lebanon?” It spoke of missing the meadows, the beautiful nature, and the early memories.

Hankash, Fairuz, Rahbanis

But also, he brought to Lebanon the Gibran song that he sang in Brazil. He recorded it with his voice, and then Fairuz sang the song, which became a big hit. Sometimes, I have performed this piece on the nay in concerts and people have loved it. In Lebanon, Hankash had a popular T.V. show. He was the presenter of the show, and he hosted numerous Arab performers. He presented me, along with my brother Khaled Racy and a friend of ours, Souhail Humsi. We were students at the American University of Beirut. We called ourselves “The University Trio.” We sang, performed, and composed the songs. We appeared several times on Hankash’s show. We became well-known at the time in Lebanon. That was the 1960s, and when I went to Brazil much later, I found some photographs of Hankash with one of my uncles who had immigrated to Brazil decades ago. Hankash died in 1979. So that is the story of Hankash and the Gibran connection.

B.E.: That’s wonderful. So Hankash is somewhat emblematic of what you referred to earlier as a “renaissance,” a cultural renaissance that has to do with both poetry and music that happens, directed by Lebanese and Syrian immigrants, but it’s happening in Brazil.

A.J.R.: Yes. During the early decades of the 20th century, the 20s and 30s especially, the immigrant world of Brazil experienced this cultural revival. What they couldn’t do back home at the time, given the political and economic circumstances, they created in Brazil. They achieved success in business, in establishing themselves, but also in the production of literature and poetry. They published so many journals in Arabic, and that brings us to names such as Shukri al-Khouri and others who were pioneers in bringing the Arabic script to Brazil. One may think they were isolated in Brazil, but when you look at the various magazines, you see that they are advertising recordings by the most famous Arab singers of the 1920s. These recordings were sold in local Arab record stores in São Paulo. São Paulo was the main focus for the many that lived and worked there, although there were in other places as well. They also hosted theatrical groups from Egypt, and later on, folkloric troupes from the homeland. The great Lebanese singer Wadi‘ al-Safi spent a few years in Brazil and became an immigrant superstar. He went back to Lebanon and sang about the immigrants’ nostalgia and begged the immigrants to come back and visit the homeland, which is eager to receive them.

But, to go back to the whole concept of cultural revival, I think toward the middle of the century, the literary movement receded given the social and political circumstances in Brazil. However, the revival itself was important to the extent that many poets and writers back home were inspired by the literary work of the mahjar, which means the “place of immigration.” A terminology was created, the shi‘r al-mahjar, which means “the poetry from the place of immigration.” It became something like a modern literary genre. Many collections contained that type of poetry.

B.E.: That helps a lot. I am interested in your own experience of Brazil when you went there recently with Robert Moser. You must have been quite curious about it. Tell us how you found the experience of being there.

A.J.R.: I think I encountered layers of musical culture, early layers and later ones, actually. Both Robert and I were able to locate bookstores that had old magazines with published advertisements for recordings. So we became much more aware of the context, what people listened to and produced in terms of music: who sang, who danced, and so on. We saw first-hand performances in social clubs. Over the years, the clubs have been central in the life of the community. They have played a very important cultural role. The clubs have been named after certain towns, or after certain regions in Syria or Lebanon. And those clubs have presented dancers and musicians, as well as social activities. For further information on the cultural life of the Syrian-Lebanese diaspora in Brazil, I suggest reading John Tofik Karam’s excellent work Another Arabesque: Syrian-Lebanese Ethnicity in Neoliberal Brazil (Temple University Press, 2007).

"Beirute" steak sandwitch, sold in Brazil

Some clubs still exist. For example, there was one in Rio de Janeiro that invited dancers and musicians, and that was a big social venue. The belly dance scene is amazing now, not just among immigrants, but within the larger Brazilian community. Arab music has become very important. My wife Barbara Racy and I stayed in an apartment, and we often heard Arab music coming from the windows of the neighbors. We met the neighbors and nobody looked Lebanese or Syrian, but we were hearing Egyptian belly dance music, popular music. Barbara, Robert, and I also went to a party, a kind of Arab festival with maybe twenty or more dancers. It was fabulous. It reminded me of big Hollywood events. The dancers were Brazilian, and they were excellent.

Something that also struck us is that many of the musicians in the orchestra have come directly from the Arab world more recently. So the newest musical layer has come directly to Brazil through globalization, if you will, or through direct contact with people coming over from Lebanon, probably after the civil war. Some also came from Syria. There is also one Syrian artist, Tony Mozayek, who is quite famous in Brazil, a singer and his musical group. They accompany dancers and give concerts of traditional Arab music.

Other than that, there are CD stores, especially in São Paulo. Many of second or third generation immigrants have been well integrated into the musical scene of Brazil. Some of them perform music that is Brazilian. Some, such as the guitar duo the Assad Brothers, Sergio and Odair Assad, are well-known internationally. The Assad Brothers are absolutely amazing, virtuoso creative musicians. They play classical guitars, and members of their families sometimes play with them. They tour all over the world. One of the pieces actually that Sergio Assad has done incorporates an Arab theme, and it’s very well-done. It takes that theme, the introduction from an Umm Kulthum song, “Ruba‘iyyat al-Khayyam.” This is a famous song of Umm Kulthum, based on the poetry by Khayyam, a Persian poet in Arabic translation. And Sergio treats it in a way that is very suitable for the style, the harmony, and the style of guitar playing. It also introduces a rhythmic pattern that gives the piece a very distinctive quality.

B.E.: Oh, yes. That’s a wonderful piece, “Tahhiyya Li Ossoulina” (Tahiyya li-Usulina) from their 2007 CD Jardim Abandonado. What can you tell us about the Assads?

A.J.R.: The Assad Brothers, Sérgio and Odair, are really grounded in Brazilian music, but also in the classical repertoire. And they have added their own phenomenal virtuosity to their performances. They have done many recordings that became internationally known. I spoke with him on the phone more than once, and he was helpful in giving me contacts with people that I met in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. There we met conductors and opera house directors who all come from Lebanese backgrounds, probably third generation immigrants.

The Assad Brothers are interested in launching a project that celebrates their roots and would involve a tour in this country, joined by a Lebanese singer, and I think a Lebanese drummer. They are really open and willing to bring to their music things that are artistically and symbolically significant to their roots.

B.E.: Very interesting story. You’ve really painted a remarkable picture of a kind of hidden aspect of Brazil. Robert mentioned that there seems to be some connection between the music, and particularly the percussion music, of the Brazilian northeast and Mediterranean music. And I wonder if you could talk about that. Can we find any good examples of that?

A.J.R.: I think when we were in Brazil, it was obvious to us that many Brazilian musicologists and ethnomusicologists took so much interest in the northeast of Brazil. The general feeling is that if you really want to look for connections with Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, or for Arab links, that would be a good place to look into. I would say not just the rhythm and the instruments, but also the style of singing, maybe the melodies, maybe the ornaments and things like that. There are books written by local scholars on the topic. This and similar topics are hard to study, especially when the links have taken place so many years ago, even centuries ago, and how things have been locally adapted and changed. It’s a challenge, but certainly that part of Brazil is a fascinating area for historical and cultural research.

Many people are, of course, interested in the African influence in the samba and other things. And, certainly, the European influence is there, in turn, influenced by the Moorish tradition. Interestingly enough, immigrant poets from Lebanon and Syria established a literary league, the Andalusian League, in Brazil. The word “Andalusian” seems to be symbolically important. It suggests, at least indirectly, that the link between the Arab world and Brazil is not new, but much older.

B.E.: Yes, Robert mentioned that there were these important literary societies in various Lebanese immigrant communities.

Khalil Gibran

A.J.R.: Yes. North America had the Pen League with Gibran and N‘aymi and many others. North America, of course, would be a topic for another program. Many famous Lebanese poets in the eastern part of the United States were part of another literary renaissance.

B.E.: Tell us a little bit about the immigrant poet, Shukri al-Khouri.

A.J.R.: Shukri al-Khouri is an interesting figure in the Brazilian immigrant experience. He was born in a Lebanese village called Bikfayya. He wrote against the Ottoman authorities and was condemned to death, but he fled to Brazil actually in 1898. In Brazil he pursued a writing career. He wrote in Arabic. My information comes from one of his relatives in Rio de Janeiro. She’s also indirectly related to my own relatives in Brazil. Al-Khouri had a distinguished profile in the community. He also wrote in Argentinean journals. He brought the Arabic printing letters to Brazil. Before that, printed letters used to be set individually by hand. Around 1906, he established a very important magazine called Abu al-Hawl (The Sphinx). The magazine lasted for almost 44 years.

He returned to Lebanon to get married, then came back to Brazil and became the Consul for Lebanon there. He was well-connected, very influential, and he defended the immigrant community. I was told that during the French Mandate over Lebanon, he successfully challenged the French authorities who tried to restrict the Lebanese emigrations to the West. He played an instrumental role in facilitating their travels. One interesting story about him is that, towards the end of his life, he met someone who was going to Lebanon. The man asked Shukri, “Do you need anything from Lebanon?” Shukri said, “Bring me a fistful of earth from Lebanon.” And, indeed, that person brought back a fistful of earth. When Shukri died, according to his prior wish, the fistful of earth went into his coffin. He was buried with a piece of the homeland with him.

B.E.: Wow, that’s really poignant.

A.J.R.: The Ma‘louf family is another well-known immigrant family, a very large family from the same village that Hankash came from. They too went to Brazil and wrote quite a bit of poetry. Some of it was philosophical and also expressed nostalgia for the land they came from. Many poems from the community talked about the incoming immigrants’ state of limbo, not being here and not being there. Some of my uncles also wrote about the immigrants’ experience. Many immigrants were responsible for supporting their parents in Lebanon, and had to send them money, but also had to work hard to establish their own lives. They were sad to be away from home, but also had to work hard to build themselves in a new country, with a new culture, a new language, and so on. And, I must say, some of them became extremely successful financially, socially, and politically. Many of their descendants reached very high posts in the Brazilian system. Some became literary figures and wrote about a wide spectrum of topics and local concerns.

B.E.: And you say you experienced this indirectly as a young student in Lebanon.

A.J.R.: When I was growing up in Lebanon, the image of Brazil had a strong presence in our consciousness. That came to us through the letters our relatives wrote back—nostalgic, and in some cases telling about their own children, their own lives. When I visited my late maternal uncle’s family in São Paulo, I found some of the letters that my parents had sent them. In one letter from the early 1940s, my father wrote to his brother-in-law’s family telling them about my birth.

Also, besides the literature that we read in school by the poets of the mahjar, some of the journals that were published in São Paulo, especially those by my paternal uncles, were sent to my parents. My father, being a poet and writer himself, was proud to have them in our family’s house in the southern Lebanese village of Ibl al-Saqi. We would leaf through them and read some of the Arabic articles, many of them written by my uncles, who, before leaving for Brazil, had studied at the American University of Beirut and were good writers. Often, it was the well-educated people who ended up in Brazil.

B.E.: I want to ask you about another art form, belly dancing. I gather there is a vibrant Middle Eastern belly dancing scene in Brazil. This is interesting as this kind of dancing seems to be more and more out of favor in the places where it was born. Certainly we saw that in Egypt.

A.J.R.: If you go to some of the gala events of belly dancing in Rio de Janeiro or São Paulo, you sense an Orientalist depiction of the East. The waiters are dressed in Arabian gowns, and the decor of the night clubs goes with that. It’s conceivable that the openness of Brazilian society and the deeply rooted culture of dance there have encouraged a movement that was already internationalized. Today, belly dancing has become quite prevalent in Europe—in Sweden, France, Germany and other places. Also there has been a flourishing belly dance scene in the United States. In Brazil, belly dancing seems to go along with the popularity of other Arab cultural factors, such as food. There’s a famous fast food chain in Brazil that sells Lebanese dishes, like kibbi and tabbuli. It’s called Habib. You even find little shacks, stores, and restaurants that sell things like that.

B.E.: Is there any particular character to the belly dancing that you saw in Brazil? Do they merge Brazilian and Middle Eastern music, for example?

A.J.R.: My wife Barbara Racy is a specialist; she studied dance ethnology and dance movement and therapy at UCLA; she is a clinical psychologist by profession. She has a keen eye for that. I think we noticed that many dancers adhered to the eastern style, and in other cases, it seemed that there was some kind of hybridity in it. But the artistry was aesthetically moving, well-done certainly. Some of the dancers we met and spoke to also did flamenco dancing. They love it and seemed proud of it. We found magazines that specialize in the belly dance and the music that goes with it. However, although the ambiance of the dance events brings about Orientalist impressions of a generic Middle East, many Brazilian dancers, we are told, visited, danced in, and studied the languages of some Middle Eastern countries. Similarly, many musical CDs from the Arab world have been sold at Brazilian dance events.

B.E.: You have mentioned this theme of nostalgia, as well as a certain rebelliousness in all this immigrant art. Robert Moser talked about how distance from the homeland and authority structures allowed for a sense of freedom and license. Can you talk about that?

A.J.R.: Indeed. Especially during the early immigration years, many felt that they had left a world that was oppressive, stricken by poverty, famine, and disease. My late father remembered the old send-offs, or farewells, when people left Lebanon. These were very emotional events; many parents would say, “Go, my son. Go away. Don’t get stuck with this place.” They would walk with them in a group to the outskirts of our home village, to the place where the carts and the mules would take them with their belongings on a couple of days trip to the port in Beirut. You know, when a mother hugs her 17-year old son, knowing that she may not see him again, that is a very painful feeling of separation. During these farewells, fraqiyyat were sometimes sung, especially by the female family members. Fraqiyyat means “songs of separation,” or “songs of departure.” This song genre is considered very sad. It is traditionally performed by grieving women as part of the Lebanese funeral lament ritual. Incidentally, Lebanese laments were the topic of my master’s thesis. But then, the young people go to Brazil, they succeed, they write letters, they send money, and they establish themselves. And sometimes they come back. In the early 1950s, one of my relatives in Brazil, philanthropist Karam Racy, donated an electric generator to our village. The village enjoyed home and street lighting while other towns around it were still using kerosene lamps.

Lebanese family in Brazil, 1920

Today, the immigrant community is somewhat different from some forty years ago when my parents visited Brazil, at a time when many immigrants still knew the Arabic language and read Arabic books, including those that my father wrote. However, in many cases, the homeland has been rediscovered, or perhaps reimagined. Some of the descendants have studied the language. Arabic is taught in some Lebanese community clubs in Brazil. Others have made exploratory trips to the Arab world, or have expressed their sense of roots through their musical compositions. As a Lebanese-American, I fully appreciate the place of nostalgia in the immigrant experience. I also better understand the processes of acculturation that the immigrants undergo. Similarly, I also understand the complex and multilayered nature of our identity in the larger world we live in.

B.E.: That’s great, A. J. Really wonderful. Thank you so much for this interview.