In the wake of Tuareg singer/songwriter/guitarist Bombino’s recent Grammy nomination, we’re experiencing a winter storm of blues and rock from the hot, dry Sahara. Three 2019 releases so far this year showcase the variety in this surging genre, irresistible to anyone who grew up with classic rock ‘n’ roll.

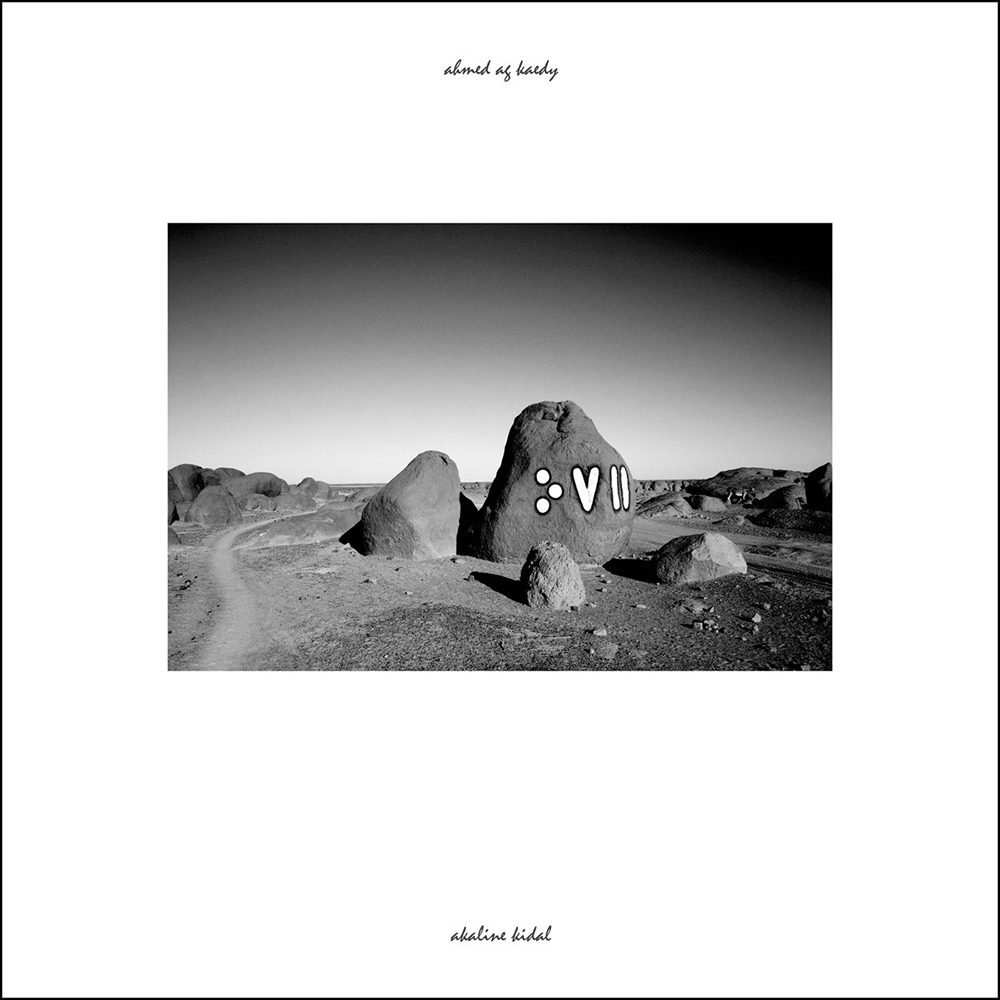

Ahmed Ag Kaedy’s Akaline Kidal (Sahelsounds) exhibits the gentle, lulling side of Tuareg music. Of these releases, this is the closest to the origins of Tuareg folk-rock (Ishumar), which was forged in refugee camps during the drought- and war-challenged era of 1960s and '70s. One imagines a still, half-moon night in the desert, a weary traveler comforting companions with songs around a flickering fire. Ag Kaedy’s voice is soft, but clear and raspy, unforced, almost lazy. Songs often unfold over a slow, broken triplet canter, like the lope of the camel the musician has been riding all through a long day. In fact, this session was recorded in a basement in Portland, Oregon, but no matter. The clarity of the recording only amplifies the authenticity of the performance.

Ag Kaedy now lives in exile from his hometown, Kidal, where Ishumar pioneers Tinariwen recorded their debut international album in a local radio station. These days, Kidal still smolders with tension and flashes of violence that linger in northern Mali following the tumultuous events of 2012-13. Exile surely burnishes Ag Kaedy’s languorous vocal. It mostly feels pretty downbeat, though his mood lifts here and there, as on “Asin Oral,” pulsing and restless as a Zulu walking song, graced with a high ethereal vocal melody. Ag Kaedy is not the most polished or virtuosic Tuareg guitarist on the scene, but he’s solid, and it is a treat to hear the style stripped down to its essence.

If Ag Kaedy’s sound conjures a peaceful night in the desert, Mdou Moctar’s Ilana (The Creator) (Sahelsounds) is more like a raging sandstorm. Moctar starred in Sahelsounds’ brilliant reimagining of Prince’s Purple Rain a few years back, and his follow-up album, Sousoume Tamachek, was a quiet, mostly acoustic affair. Here the ensemble is full on, with amps cranked to 11 and reverb and delay in overdrive creating the sense of a vast maelstrom. The opening track, “Kamane Tarhanin,” begins with drones and distant voices, then opens into a Tuareg rock rhythm with sharp, clear lead guitar in the foreground and a roar of echoey distortion underneath, and it winds up in a slamming fury of sound.

Moctar sings on more than half these tracks, but his voice is often back in the mix, melodious but rarely commanding the center. To my ears, this is a guitar record. Moctar employs a range of rocking guitar tones, brash roadhouse blues on “Inizgam,” sweet, clear, reverb-drenched liquidity on “Tumastin,” and all-out, top-of-the-fretboard shredding over an ambient sonic volcano on “Takamba.” This is as fierce an example of the Tuareg genre as we’ve heard, and testimony to this remarkable artist’s virtuosity and range. Even with no lyric translation, Ilana forcefully communicates the anguish and uncertainty of the Tuareg predicament in the Sahara.

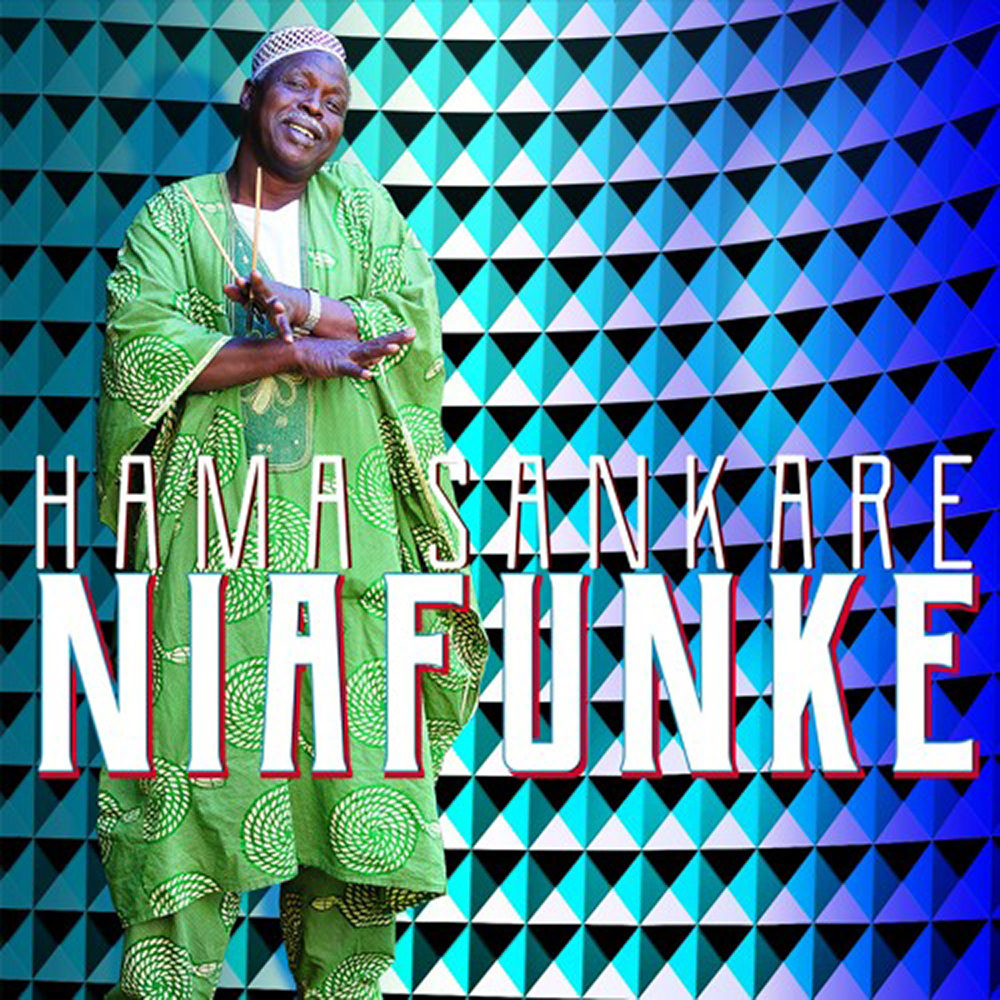

Hama Sankare’s Niafunke (Clermont Music) comes from a somewhat different place. Sankare is Songhai, not Tuareg, and we know him best from his years playing calabash percussion and singing backup for the legendary desert bluesman Ali Farka Toure. This is Sankare’s second solo album, and like the first, it reveals him to be a most compelling front man, largely due to his powerful, raspy voice, full of gravity and moral conviction. Here, Sankare calls for honorable comportment between men and women, decries unemployment, praises heroes and benefactors, and prays for peace in Mali, which he feels is being torn apart by conflict.

The Songhai and Tuareg have long coexisted—farmers and nomads, exchanging services and at times clashing—so it’s natural that their musical natures align. As with the two Tuareg releases, guitars reign over the soundscape here. On lead guitar, Oumar Konate shows himself to be a consummate and versatile instrumentalist, employing an even broader array of sounds than Moctar—though none quite as ferocious. The specter of Ali Farka hovers within these elegantly constructed tracks, inevitably, with Yoro Cisse on monochord and Afel Bocoum speaking sagely and singing harmony—both Cisse and Boucoum are, like Sankare, veterans of Ali Farka’s posse. There are even some traditional pieces we recognize from that era. What is impressive here is that none of this feels imitative. The ensemble is big and rich, the range of rhythms satisfying, and the sense of freshness and camaraderie palpable. Kudos in particular to Konate for evoking Farka’s spirit on guitar without ever imitating him.

Related Audio Programs