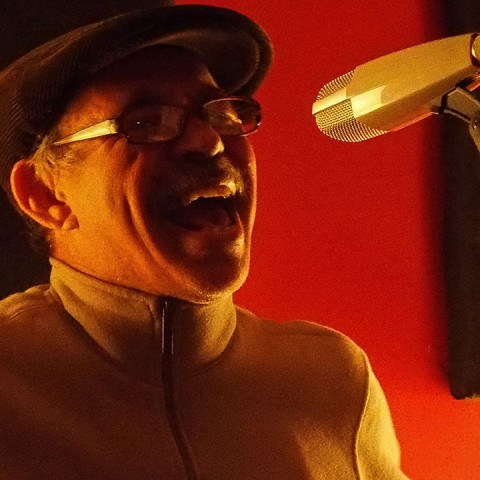

Abraham Rodriguez’s combination of soulful voice and skillful delivery has made him one of the most sought-after musicians in the salsa and folkloric scenes. He has been touring for over 20 years and has worked with renowned artists such as Manuel "El Llanero” Olivera, Eugenio “Totico” Arango, Orlando “Puntilla” Ríos, Grupo Folklorico y Experimental Nuevayorquino, and Michelle Rosewoman, to name a few. When it comes to Afro-Cuban drumming and singing, especially, Abe is a seasoned practitioner and staple in the Regla de Ocha community.

It is Abraham’s knowledge of the sacred batá rhythms, prayers and songs that inspired guitarist and producer Jacob Plasse to collaborate and create a new project. The result is the four-song EP called Rezos (Prayer) with a new group, Okonkolo, consisting of Rodriguez on batá and lead vocals. The prayers, songs and rhythms that make up Okonkolo’s debut are complex, beautiful and of a tradition that existed before time itself.

The batás, the sacred drums of the orishas, have appeared in contemporary music since Irakere’s 1974 mega-hit “Bacalao Con Pan.” In 1976, Tipica ’73 released “Yo Bailo de Todo.” Both songs, however, incorporated batás and their unique dialogue as a percussive vessel, enhancing the songs’ rhythmic sound, as well as informing the world of their unique cultural identity. The batás played around the band’s instrumentation and arrangements. With Rezos, the band plays around the batás, the prayer and song.

I had a chance to sit with Abraham to discuss his beginnings in music, religion and Rezos. We will also hear from Jacob and his experience with Rezos.

Julissa Vale: Abe, tell me about your beginnings in music.

Abraham Rodriguez: I’ve been playing music professionally since I was 14. My professional debut was at a place called the Frolic in Revere Beach, Boston with my uncle in a trio. My uncle was a timbalero and my father used to sing with Mon Rivera and Vitín Avilés.

Is your family from Mayaguez, Puerto Rico?

Yes, and they all grew up with each other. One day, my father’s friend, Willie "Tirantula (Tarantula)," saw me mimicking a timbales solo and told my father, “Abe is a musician.” My father had no idea that I was musically inclined until I started banging on my grandparents’ pots and ashtrays. I was fascinated, at the time, by Mongo Santamaría and his song “Margarito” in the ‘60s. But way before that, at the age of three, my father taught me, word for word, a bolero by Benny Moré, “Por Una Madre,” and I’ve been singing since.

When did you get back to New York?

Around 1970. There was a record store called Angelo’s Record Shop on 165th Street. They had a speaker the size of the door and they were playing “Guaguanco Matancero.” I was blown away! I was hearing Kako, Ismael Rivera, Patato and thought, “God! I want to play like that!” So I ran up, took the quinto from my house and started playing, imitating the sound, you know. Then two Cubans that played with Totico saw me and took me to see Totico. I was 15. I began singing guiros with him around 1971, 1972. After that, I started going to Central Park to do the rumbas and started to imitate the songs that I had learned. It was natural for me to sing so I became one of the young kids that would sing guaguancos.

Then a wonderful experience happened. I met a man named Manuel Martín Olivera, “El Llanero Solitario.” I used to play a quinto alborotoso (disorderly quinto drumming) because we didn’t have clave and we didn’t know where it was. We did clave in our own way. El Llanero is the one who really taught me how to sing guaguancos. Totico started me off with the orisha songs but it was my godfather, Puntilla, who really molded me into the actual religious stuff.

Tell me about your godfather, Puntilla.

My godfather, Orlando "Puntilla" Ríos, was a singer and percussionist born in La Havana. He came to the United States in 1980 with the Mariel boatlift and brought along with him a tremendous knowledge of Afro-Cuban folklore. He was a great teacher and great mentor.

Now, before Padrino got here, there was Julito Collazo and Juan Candelo. Juan Candelo had fundamento and his family had been here since the ‘40s. We also had West Coast drummers like Francisco Aguabella and Armando Peraza. But, Padrino was the foundation of the religious community here in New York.

He was also criticized. There is an important part in our ceremonial drumming called the oro seco. At the time of his arrival, many in our community either didn’t’ know it had to be played or didn’t know how to play it. Padrino was criticized at first for the way he positioned the drummers at the orisha’s throne. See, during this prayer, my godfather faced the throne as opposed to playing on the side of it and many practitioners considered him rude. They thought he was shunning them by giving them his back. He was also criticized because he was inclusive and he broke the rules. He taught all that wanted to learn. Today he’s known as “the grandfather of the Aña” here in the United States. In 1994, I became his first godchild. It’s because of his mentoring that I continue on with the traditions and pass on this great legacy.

You’ve performed with a plethora of artists and have had several impressive projects. Your latest, Rezos (Prayer) is a four-song EP produced by guitarist Jacob Plasse. How did this project come to be?

I met Jacob in the Lower East Side during one of my gigs at Plan B. He was very curious and interested in what I was doing and wanted to eventually collaborate on something together. I am very impressed with the project and all of the musicians and singers that participated in it. Gene Golden and Sado Iroro are both playing batás and singing coro. Jadele McPherson is the lead vocalist on "Oba." She has a beautiful voice.

Jadele’s delivery is sincere and shines throughout the song. The strings accompany the prayer beautifully and the vocal harmonies are engaging and also pretty. The following three songs are “Obatala,” “Ochun” and "Wolenche For Chango."

I am a child of Chango and Ochun. Wolenche is Chango’s dance. In this dance, Chango is flaunting his strength. Remember he’s the orisha of drumming, dancing, thunder, fire, male virility, and leadership. Ochun is the orisha of the river and represents love and sweetness. Obatala is the wise creator of earth and the sculptor of mankind. Remember, the batás speak the Yoruba language and invoke the orisha. Each one has their individual prayers and songs of praise.

What made you choose the name Okonkolo for the project?

Jacob Plasse: When we were recording, Abe was talking with Gene Golden about how drummers begin their studies playing the okónkolo, and are quick to want to move forward to playing the other larger drums; often the drummers want to progress before they are actually ready. Gene agreed and said it was ironic because to him the okónkolo is the most important batá drum in the ensemble as it keeps the time and grounds the other rhythms. So for me the name Okonkolo represents these ideas--how growing as an artist takes time and patience, and that the things that seem simplest are often the most important, and actually the most difficult. It’s the Elegua or the tambor (drum), la clave. Also, the Iyá (mother drum) and the Itótele (father drum) have to work around the baby, Okónkolo.

Can you describe the recording process? Did you consider what you were playing as engaging in the batá drums’ dialogue?

Rezos producer Jacob Plasse.

Jacob Plasse: The recording process was an evolution for me as well; I learned so much. After I recorded the group playing together live, I started listening to the sessions over and over again. I had a sense of the intricacies of the patterns, but I began focusing in on each drum and trying to understand the perspective from each drummer’s point of view. It's very disorienting at first, and it was a big step forward for me to really hear each drum's place in the rhythms. After that, I began sitting at the piano or guitar and trying to figure out rhythms that would complement the drums and harmonies that would fit with the chants; it took a long time. Then I began editing the performances and writing string parts and horn parts with Mike Eckroth, as well as figuring out guitar tones that would evoke the moods I wanted to convey. Once all that was laid down I met up with Nick Movshon who really did an amazing job of locking his bass lines in with the drums; I wanted to use these songs to create something unique and new, but that honored the spirit of the prayers.

Are there any dates set for an Okonkolo show?

Jacob Plasse: We have been busy in the studio finishing a second EP which will complete the album, and also making some more videos with some incredible dancers; I want to put a performance together that combines elements of the dance, ritual and music.

Abe, what do you expect from this project?

I expect everything and nothing. It’s like a new chakra, a wave in the ocean. I want the world to hear it.

Rezos is a genuine project worthy of recognition and I look forward to hearing the complete album.