Ade Bantu is the leader of the Lagos-based big band BANTU. Prior to the pandemic, Bantu has hosted a monthly event at Freedom Park called Afropolitan Vibes. The band performs but always with invited guests from other areas of Nigerian music. It’s a brilliant showcase and forum that Afropop was lucky to experience in 2017. Bantu has a new album called Everybody Get Agenda. Banning Eyre reached Ade by Zoom in Germany to talk about the album and recent events in Nigeria, like the anti-police brutality, #EndSARS movement. Here’s their conversation.

Banning: Ade, how are you?

Ade Bantu: I’m very good. Very good.

The album is great. I've really been enjoying it. I'm putting together a show on new sounds out of Lagos, and I'm amazed by the volume and variety. The scene there is really boiling over.

Yeah, well 200 million people, what do you expect?

I guess that's it. But it's impressive. Let's talk about your album, Everybody Get Agenda. Tell me how you feel that this album fits into the Nigerian scene today.

I'm fortunate in so many ways, fortunate because here I am in my late 40s. I'm still doing music, and it has some kind of relevance. And then I've also been able to taste pop success in Nigeria with my brother, Patrice, and the founding members of BANTU. We've been “stars” in inverted commas for a minute, and now I feel like I'm doing music that I want to stand the test of time. So my artistic ego is fulfilled on many levels, and that kind of helps me to stay focused, and add to the fact that I have created my own niche literally in Lagos by coming up with this event Afropolitan Vibes.

Your monthly live showcase at Muri Okunola Park. A great event!

Exactly. So it kind of grew steadily, and that has kind of like led to a renaissance of live music in Nigeria, because a lot of these younger artists that I invite to perform with the band, they were all kind of, “O.K., this is the way to go.” For example people like Burna Boy and Yemi Alade, so when you are able to influence popular culture directly or indirectly, I think you are doing the right thing. And that also comes from me having the privilege of having lived in Germany and understanding what a European audience or an American audience expects from a performer or performance, and understanding that the dynamics of music have changed already by the time I moved to Nigeria 10 years ago. It wasn't so much about album sales. It was about touring. That was the way you were going to make the money. You better put up a good show, and it better sound right, and then you can make the money and there's a sustainability to what you're doing, so all of that kind of adds up.

Well, you've got a great band, probably the hottest horn section in Nigeria.

It’s such an honor to have that band. Sometimes I have to pinch myself. Is this happening?. It is beautiful because we have evolved over the years, trying to define our sound, trying to be comfortable with who we are individually or collectively, which is normal in a big band. But especially in Bantu because we don't have one chief composer. Everybody in the band is a composer. So I have to hear everybody out and get everybody's idea out as well. So that might be a bit more cumbersome, but I feel it connects to what I always believed music should be about is communal, and is kind of the rock ’n' roll spirit.

I get that. Let's talk about the album. Is there an overriding goal or inspiration before we talk about individual songs?

For me, I needed to do this album in order not to lose my mind in Nigeria. Because we've gotten to a point where I just felt like there was so much tension outside and within me as well. Why so? Because I started writing the songs around the time when Nigeria was about to go through elections, the recent elections, and when I just saw the shenanigans going on around the country, politicians with their grand promises and voters’ fatigue, and seeing close friends who said, "No, I'm not going to partake in this at all. I'm not going to exercise my right." And me, knowing what it means to exercise your right, especially since I was also once blacklisted, and I was once exiled. I couldn't go to Nigeria based on what I was doing with the movement against General Sani Abacha.

So having all of that in mind, I was just very frustrated, depressed. I didn't know any way forward other than to articulate my frustration, my anger, and what I imagine the future to be through music. Or else I might have just packed my stuff and left Nigeria and move to another country or continent, or maybe to an island and say I'm done. I think I was at a breaking point. This happens to a lot of creative people. When you are in an authoritarian or dictatorial kind of situation where your rights are being infringed upon, and where you just feel suffocated, and no one around you seems to understand or see it, then your kind of like, “O.K., maybe I don't belong here.” So the music was therapeutic.

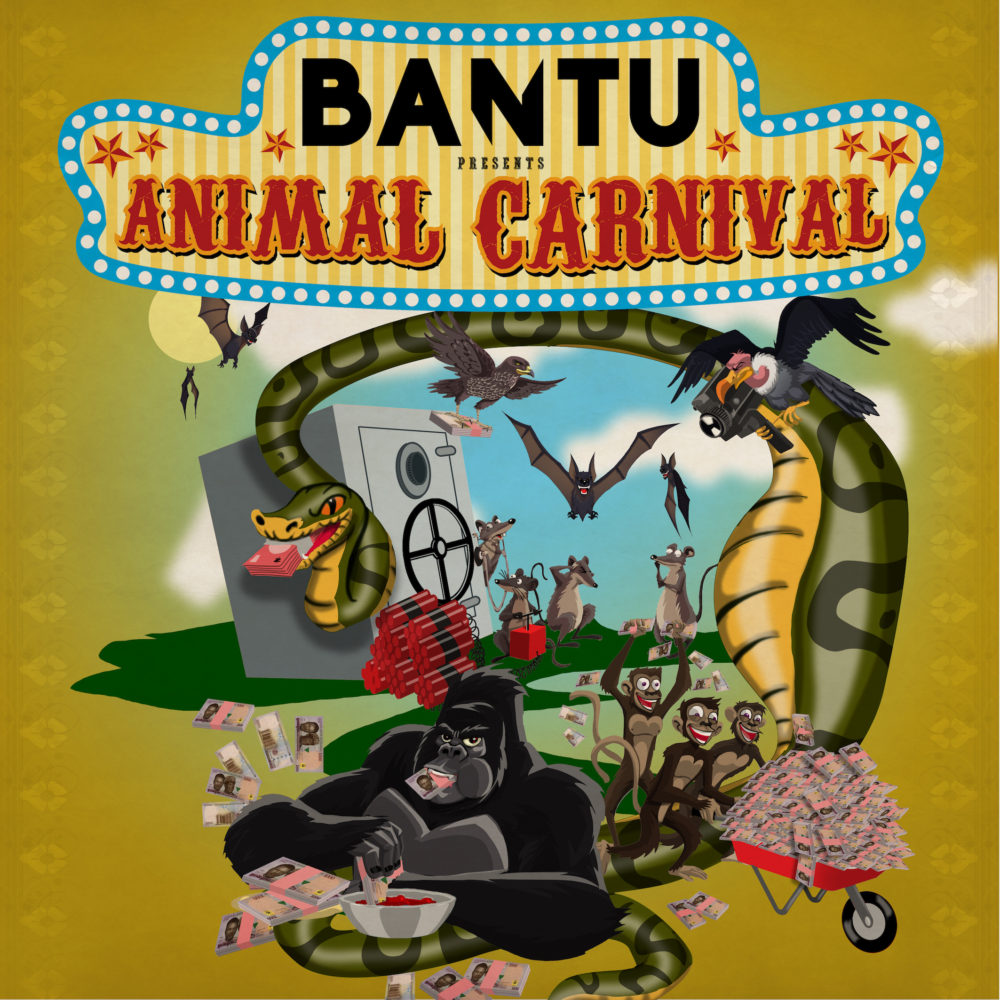

Let's talk about the lead track "Animal Carnival."

“Animal Carnival” I mean, I just had to write that. It was begging to be written, right? When you have a situation where a sitting senator comes before the cameras and says, “You know what? One of our colleagues was given the monies that we have gathered at the Northern Senators’ Forum, and they say that one of their colleagues took the money to his farmhouse…” Then you already go, "Huh? Did he go to the bank, cash out the money and put it in his farmhouse.” But then it gets better. “And the farm house was raided, [and here it comes] by monkeys, [and I quote] they carted away the money!"

So you hear this in front of a live audience. It's a press conference, and, oh no, this is the height of it. And just when you thought it couldn't get any better, there's a lady, a civil servant who's in charge of the accounts of the examination council. She's in front of a commission inquiring about missing money, and she says it's the ritual snake that went into the safe and swallowed the money. And you're like, “No, this is not possible.” And then a zoo in Kano, they said that monies were missing because a gorilla had swallowed it. You can't make this up. These animals are taking over Nigeria! So, it begs to be written.

That's amazing. Even Trump hasn't gone that far.

No, he can't. You can't make these things up. So I had to work around that theme. So that's why say we started with the overall theme “Animal Carnival” and took it from there. So it's kind of like a jolly, feel-good song. It's like the album opener as well, but you don't really understand until you pay close attention and it's like, hey, what's he's singing about? 70 million gone? What, what? So it's kind of like, O.K. That's why we also had to put out the lyrics on the video as well, so people can kind of follow it.

Let's talk about your other video song "Disrupt the Program."

“Disrupt the Program.” It says it all. I want people to stand up for their rights. What I saw in Nigeria, even before the End SARS movement, there was a lot of social media activism. You have this young generation of Nigerians, but who didn't really go through the dictatorial period of Nigerian politics. They didn't experience it. I won’t claim they don't understand. But they didn't experience it. So they are kind of free in the way they express themselves, the way they critique government on social media. But what I always felt was: how do we translate that into action? So I feel like we need a call to action. We need to make people understand that they have to go out onto the streets. You have to put your body in the line of fire, because that's how it works. If you see what happened in Tunisia, in Sudan, if you see what's going on in Uganda, other parts of Africa. South Africa, all of that. This translates to other forms of struggle across the globe. If you don't confront the state with your body, with your presence, nothing will change. And that's why I felt like we needed to make this demand. They have to feel our pain.

That's why we say "put some sand in their gari.” Gari is pretty much cassava you eat like fufu. But when you put sand in it, then you have a problem, you can't swallow it. You can't chew it. So we want to make sure they actually feel the pain that we are feeling. Because this disconnection, you have a generation of a looting class in Nigeria that has been around politics ever since we gained our independence in 1960. So you have a class that is pretty much a second generation of looters. And then they are disconnected from my reality and the reality of the average Nigerian. So that disconnect, again that obsessive-compulsive kleptocratic behavior, it just kind of sucks the life out of everyone, and that's why the country is not progressing. So that's why I felt like I needed to do that song.

It's a call to action. You know, reading about the End SARS movement from abroad, I get the feeling that something new is happening in Nigeria, that there's a new spirit of activism among the people, and maybe especially among popular artists. I think of Burna Boy’s people turning up on the street to protest. It seems like an inflection point. But some of the people I've spoken to say, "Well, no, this is nothing new. This has been happening for awhile.” They don't seem to identify this moment as being pivotal. How do you see it?

I can't blame the generation for not being able to connect the dots. What you need to understand is that history is not being taught in Nigeria in the schools. So you are talking to young artists that are not schooled in their own history. And the politics of struggle within the context of Nigeria. They have fragments of information, but only when you go a step forward and you do your own personal research can you access it as a young man or woman in your 20s, because you were not taught about these things in school, right? My generation was taught history, so I could connect the dots through the formal education and then informally via uncles and aunts and whatnot. There's a bit of that disconnect

And I think also a lot of artists have been co-opted. So when the governor invites you to perform at his daughter's wedding or son's wedding, or you come to their birthday event, or you do photo ops with the president and things like that, you can't really bite the hand that feeds you. And then if you take it a step further, a lot of them have endorsement deals with big corporate bodies, so they don't want to jeopardize their future, which is very unstable as an artist anyway, especially in the commercial sector of music in Nigeria. It's very competitive.

So a lot of them would not understand it, but they do recognize that something is happening. They might not be able to point to it or put their finger on it, but they know that something pivotal is happening. Maybe they just can't articulate it, but it's interesting to see the cross pollination. So when you look at Burna Boy’s video, it is also inspired by what we did.

Our “Disrupt the Program” video came out a couple of months prior to the End SARS demonstrations. It already addressed the End SARS issue by addressing police brutality and the dehumanization of Nigerians by the police force , and by the state itself. It's very confrontational.

So Burna Boy sees it… and that's the beauty of music. We all kind of see each other and inspire each other. And it's also good to see how Seun Kuti is positioning himself, not only as a musician, not only as an activist, but also as a leader of a political party that is registered, a movement. So he's galvanizing all the support among young people, and also educating them politically. Kind of like doing what his dad would do.

There is a long interview with Seun on YouTube. It’s excellent, but I would kind of expect that from him. Not so much from an artist like Tiwa Savage, who has also been outspoken. That seems like something new, doesn't it? And of course through the genre name Afrobeats all of these artists are kind of wrapping themselves in the mantle of Fela. So they must know some of their history through that anyway.

Exactly and isn't that beautiful that they are politicized through music, especially from an iconic figures such as Fela. And I think also it's a moment of reckoning. The movement is being led by young people, especially young women, they are the core of this End SARS movement. So your audience is now expecting you to act out their frustration. It doesn't have to be in the music. But you have to articulate their pain and frustration when you're giving interviews. You can't afford as a young artist in Nigeria not to be opinionated when it comes to police brutality. Even if you do not want to disrupt the powers that be. And what we mustn't forget is that every single one, even those in denial, have experienced some form of police harassment in Nigeria. We all know somebody. It's not a six degrees of separation. Immediate family members that have been harassed, that have been duped, or that might have lost their lives, so this is very real to the average Nigerian. All you need to do is be a motorist or be in a taxi or be in a bus and then get to a police checkpoint, and that's it.

What is interesting with this movement is to see how this generation deals with it. They didn't experience the worst of military dictatorship, but they are kind of helping the nation out of its trauma. How do you confront a state when you've gone through one of the most dramatic experiences on the continent, because we had a series of very brutal dictators. So the younger generation is looking at the older ones and saying, "You have failed us," which is very un-African. A lot of taboos are being addressed in a very confrontational manner which is quite refreshing. Because the submissive obedience that you are taught as a young person, where you don't question authority, when the elders are always right, this is shifting. And it's very, very liberating both for the old and young.

Fascinating. And it will be very interesting to see what comes of this. Are you seeing young political leaders who seem to be tuned into this change are potentially ready to lead the country in a new direction? Of talking beyond music, political figures who are really willing to bring about a new kind of governance in Nigeria.

Most definitely. I see it. That's why the End SARS movement was so successful. It was decentralized. That means they had learned from previous mistakes of the older generation who were always co-opted. The leadership invites you to the Statehouse and gives you some bribes and just wreaks havoc among the organization itself. But because it was decentralized, and as I said, I see a lot of women in particular leading this momentum for change, and also preparing for the next step.

The next election is 2023, and you will you see them going out there saying, “Go out there register as a voter. Make sure you choose your candidate wisely.” And some people are already saying they're going to stand for election. And what you can't forget is that you even have musicians, somebody like Banky W, a pop artist who actually put himself out there for the last elections of the House of Representatives. He actually wanted to go out there as an elected official. He didn't make the cut, but that was already successful in itself, having this pop artists say, "You know what, maybe I should dabble into politics, because I feel that we have a voice and we can bring about the change that is so desperately needed in Nigeria." So that was already indicator in itself.

And you say young women are very important in this movement. Are you talking about women with a platform, like artists, or just regular people?

I’m talking about regular women. A lot of the End SARS activists, those who were at the forefront collecting the monies, and some of whose accounts were frozen, even those who are now in front of the panels, a lot of these young activists are women. And I think we shouldn't downplay the role they play. It's a very, very important moment in history. So I see them connecting to the form of leadership that we also grew up with. Women are not docile in the Nigerian political landscape. If you look at Fela’s mother, Funmilayo Ransome Kuti, you see the anticolonial movement was also led by women, market women, housewives, as well as intellectuals who confronted the colonial government. So it's beautiful to see this projection, and to see this younger generation kind of connecting to it and taking up these leadership roles. And it's also beautiful to see that men are comfortable with it. Because it could've been the other way around. But we don't have a problem with women leading us, and it’s so important that we show the world and show ourselves, that we celebrate this.

Let's talk about a few more of the songs. The titles seem to say it all, but you always have something to add. Let's talk about "Cash and Carry."

Yeah, hey, that sums up what I was feeling when I started this album. And that's why the album title ended up being called Everyone Get Agenda. Everybody has a kind of ulterior motive. Who can you trust? You can't trust your friends, your family, I know it sounds like a constant state of paranoia, but when allegiances shift with the wind, it gets very dicey, and you really don't know how to go about life without always being all tensed up. So "Cash and Carry" says that everybody is a mercenary. That's what I feel. That's what Nigeria has turned us into. It's just desperate survival. Everybody just wants to make a quick buck and move on. Because everyone is disillusioned. This young generation or like, “O.K., our parents, our grandparents have been looting. No one has ever held them accountable. People act with impunity. We might as well continue that legacy by going into internet fraud, right? We might as well continue the stereotype and also be part of the looting enterprise.”

What about "Man Know Man"?

In Lagos, there’s a phrase that, “When man know man, then you can survive.” So that's the thing about Lagos, right? You can only survive if you know an oba, somebody in a higher position, somebody with connections who can protect you, somebody you can call on when you need a favor. For the majority of Lagosians , it's a tough one. Because how do you survive? There's this whole dream of making Lagos the next Dubai. The government is constantly coming up with these grand projects. They’re building, and Lagos is becoming like this global city. But what happens is that you criminalize poverty. And I saw it my own backyard. I woke up on a Sunday, and the squatter community next to me, they were kicked out. I just woke up and I saw a battalion of army officers. I saw police officers as well. And I saw people running around with their possessions on their heads. And they literally bulldozed the entire squatter camp and set houses ablaze, so that they could now claim the land and then build the most expensive estates for the nouveau riche in Lagos. So when you see all of that happening, the closeness, the proximity, as an artist, you have to react. It's very traumatic.

Because one of the worst evictions in Africa happened in Nigeria in the mid-’80s. There were about one million so-called “squatters.” I don't even like that term. There was a settlement of informal workers that were being hired by the rich, so it was in close proximity to a rich area of Lagos. And the army basically sent in bulldozers, killed people and just flattened everything down. One million people displaced. There was even a book written by the Nigerian author Chris Abani. And the main character lived in that community. And the most painful thing is they use these terms to criminalize communities that have been in existence for close to 100 years. And all of a sudden you just disenfranchise them completely. You make them homeless, literally stateless, because the state of Lagos evicts you. And then they say, “Oh, because you guys migrated from the West Coast, probably from Togo or Benin, some 150 years ago from fisher communities, and eventually settled here on the shores of Lagos, you are not Lagosian. When do you stop being Lagosian?

So when you have that kind of situation, we have to sing about it. And that's why it was so important. And what I did was to write a song that is very melodic, that has a bit of an r&b soul feel, so it kind of works. It kind of sucks you in, and you're enjoying my fellow singers, the two ladies, and then before you know it, you're kind of, “O.K., this is some serious topic being shared here." So I always feel like there's a way you can kind of draw people in. I don't believe in just doing agitprop.

You do that very well. Let me ask you about one more, “Yeye Theory.”

[Laughs] Oh God, “Yeye Theory.” It’s so funny. Why am I laughing? Because our album has just debuted in the number five slot on the “world music” charts. World music! And I am critical of that term in that song, right? I say, "Oh, I'm sick and tired of us always being put in the same box with artists from India, Colombia and whatever. Just one genre." We could go on and on, this global pop. Just one genre. So it’s just kind of stupid. That's what yeye means. Stupid theory. And then Seun comes and talks about the political class, and how they just basically continue their shenanigans. They can't be bothered how social media is manipulated. All the things that are stupid and highly destructive around us. And then I found this beautiful Fela sample where he's talking about music. The song and the album end with him saying that African music is not about all this pop thing. It's about creating something of substance. So it's kind of a beautiful way to end the album. We just say, O.K., why are we doing this? Fela tells us why we are doing this. And it’s just magical when I think of Fela, Seun, and then us, on one song together. It just feels right.

The back story is that I saw Seun while I was recording the album and he said, "Hey Ade, I heard you were on tour in Germany. I heard it went well. Sorry I couldn't make it. Hey, why haven't we done a song together?” Yeah, right. How come? So I said I’ll write something, and if you like it, then we’ll record. So I finished the song and sent it to him, and he came. He was in my living room. We talked for hours, and then he wrote the lyrics on the fly, and we recorded it. And it's just so beautiful, because I see Seun grow from the 16 year-old kid that was shouldering the burden, that whole responsibility of having to continue his dad's legacy, especially with the band. He had to prove himself among these older men. So he has been the driving force behind Egypt 80. He's found his voice as an artist, as an activist.

I've always been impressed with Seun. It's funny what you say about world music. I barely want to ask people about the whole Afrobeat/Afrobeats thing. It seems like every conversation I have muddies the waters even more. People use these terms interchangeably to the point where they don't have any meaning anymore.

Totally. And what I wanted to do with the song actually was also to frame the conversation around Afrobeat and Afrobeats. So obviously I've been asked a million zillion times and expressed various opinions. It's documented. But what I wanted to do to make my listeners understand that we need to frame it around oppressive Eurocentric politics, and understand the root cause of this evil. What is most fulfilling for me is to see how young artists like Burna Boy actually disown that term. Burna Boy refuses to call his music Afrobeats with an S or Afrobeat. He just says I’m doing African pop, or whatever. He moves away. He's the one who is coining his music. It's about ownership. And then you have an artist like Adekunle Gold, who releases an album called Afro-pop, where he deliberately says, “You know what, I'm sick and tired of this Afrobeats and westerners coming with this crazy notion of what the culture and music is supposed to be or sound like.

So I think the conversations have helped, because why did we even have the situation in the first place. It's the lack of structure. When you don't have gatekeepers, when you don't have record labels, when you don't have record executives, when you don't have music journalists, people who have been trained and that understand how important it is to own your culture, to have a voice, and to be the one that leads the narrative. Then you have a situation like what we find ourselves in.

Because what happened was a young DJ in the U.K. comes up with the term for lack of a better word, which is absolutely understandable. “O.K., there’s this Fela hype. Let’s call it Afrobeats. It's easy. It tastes good. It sounds good. We can sell it. It's a no-brainer.” But what usually happens would be, as soon as he confronts a Nigerian artist, the Nigerian artist will say, "Ah, there's a problem here. We call it Naija pop. That term doesn't work for us." If there was a label, somebody would've flagged it in its infancy. But it wasn't flagged.

So what happened was young Nigerians started to tour in the U.K. and they did interviews. And they're just excited. “Oh, how does it feel like to be in London, and your sound, Man. It's all global. It's Afrobeats!” O.K., Afrobeats sounds good. I'll take it. I'll own it. Let's fly!” And then before you knew it, it becomes this monster.

That's a good synopsis. It's funny to me that a lot of artists are reverting to the term Afropop. It's funny to us, because we took that term in 1988, and by the mid-’90s, a lot of artists didn't like it anymore. It was like world music. “No, I'm not Afropop. I'm playing soukous or mbalax or juju.” So it became an uncool term. And now it's funny to find young artists running to that term to get away from Afrobeats. It's a strange world.

Whenever I hear the term Afropop, I cringe, because I know the history of the ’80s. Couldn’t we come up with something else? It's so sad. Because if you're trying to upload your music as African musician, and I'm speaking for the whole continent, on Bandcamp or Spotify, you don't have that many options in terms of categorizing your music. It's all based on white Western perception of what music is, and the musical categories that apply to music, with the omission of all others, because they are world music. It's just madness.

I hear you. I sympathize.

Yes. You are knee deep in it.

Yes, no escape. Thanks for talking. We look forward to getting your band over he when it's safe to tour again.

I can't wait. I can't wait. Believe me. I just want to tour. I haven't had a single gig all year. And it's so painful, especially with an album out. It's too dangerous. We just have to wait. But it will pass. Out of every negative, you have to find positive. That's the most important thing. It gives us the opportunity to look within. And to plan for what we want for the future.

Amen, Ade. Be well.

Related Audio Programs