On our special Hip Deep episode “The Money Show,” we explore the economics behind music in the African diaspora. In Chapter Three, we look at what has happened when foreign artists and music labels profit from African music… often without asking for permission. Listen to the full episode here.

Once upon a time in a land before disco, a downtown socialite named David Mancuso was crate-digging in a West Indian record store in Brooklyn. He came across an import 45 of makossa music, a dance genre popular in Cameroon, West Africa.

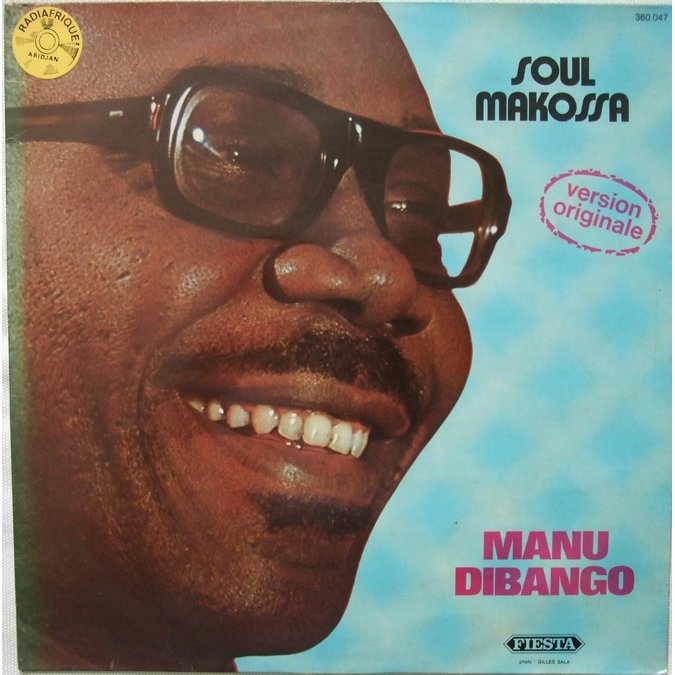

The single, “Mouvement Ewendo,” was by Manu Dibango, a Cameroonian jazzman; the title track was commissioned as a sports anthem for the Cameroonian soccer team. The B-side—a throwaway that Dibango’s label had laughed off—was “Soul Makossa,” a funk experiment that featured rhythmic chanting in Douala, a Cameroonian language, underneath a hard-hitting sax line. Mancuso began spinning the track at the popular, invite-only SoHo party he held in an abandoned factory known as The Loft.

The reaction was immediate and overwhelming. The few remaining copies in New York quickly sold out, and once a copy made its way to the black radio station WBLS, demand multiplied. Within the year, at least 23 cover versions of the song were released. “People went wild trying to find that record,” says disco DJ pioneer Nicky Siano.

Across the Atlantic, sales began to explode at Fiesta, the French label that had pressed the single. In the space of a week and a half, orders rose from 5,000 to 30,000 copies. Finally, Atlantic Records—then the pre-eminent r&b/soul label in the world—licensed the tune and released “Soul Makossa” in the States; by 1973, nine different versions of the song were on the Billboard Hot 100 chart. According to the AllMusic Guide, many cite “Soul Makossa” as the very first disco record.

By the fall of 1979, the dance fad was over—the Top 10 never saw a disco tune again. Dibango’s surprise hit had faded from view. But the rhythmic vocal chant at the heart of the song—“mama-ko mama-sa mama-makossa”—resurfaced a few years later, reshaped and repackaged for the global stage by a newly crowned king.

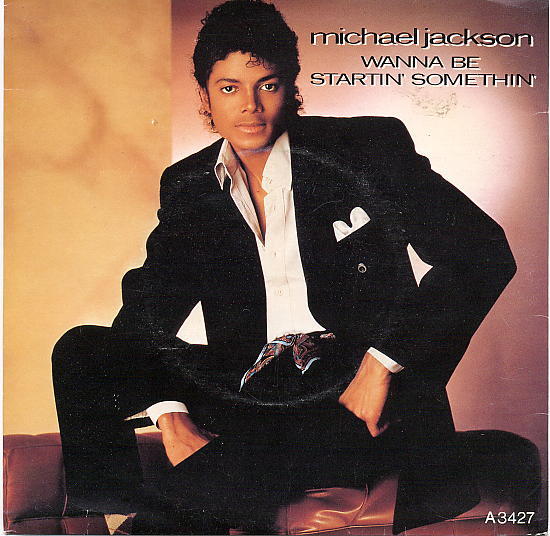

The best-selling album in music history kicks off with three sharp snare hits, followed by six minutes of perfect pop. “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’” was one of seven singles launched into the Top 5 by Thriller, Michael Jackson’s landmark 1982 LP. At 04:44, a breathless Jackson gasps “help me sing it,” as a chorus of backup singers closes out the track with a pulsing Douala incantation, a two-minute coda that’s made a permanent mark on popular music, sampled in at least 13 songs by artists from Jay-Z to J. Lo, Rihanna and Wyclef.

“Anyone who loved ‘Soul Makossa’ knows where the holy-rolling ‘mama-ko mama-sah ma-ma-makossa’ came from,” writes pop critic Eric Henderson. Thriller spent 80 weeks in the Billboard Top 10—the longest run ever by a studio album—and sold more than 65 million copies worldwide, according to a 2010 analysis by the Wall Street Journal. The sleek gatefold of the original LP lists the following credits for the jump-off track: “Produced by Quincy Jones. Written by Michael Jackson.”

At “Soul Makossa”s release, Manu Dibango had been on hard times. “To guarantee enough for Jerry and the band to stay alive on...sometimes I would go to Cameroon to play receptions financed by the banks,” writes Dibango in his autobiography. “I needed more money. Coco and I had just moved into a pretty house in Joinville, and my ailing mother moved in with us.”

“Soul Makossa” had helped to turn things around—in fact, it was one of his biggest commercial successes. But royalties had long since dropped off, and Dibango was back to playing fairly for a small, relatively niche market.

He was startled to hear, on the radio in his apartment one day, his anthemic disco chant. Friends began to call and congratulate him—the King of Pop had knighted his song! But Dibango was never paid, consulted or credited. He sued Jackson in 1986, receiving an out-of-court settlement for one million French francs.

The unattributed appropriation of African music by Western artists is an unfortunately rich and long-lasting tradition. From “The Lion Sleeps Tonight,” to Shakira’s World Cup anthem “Waka Waka,” African artists have seen their music used to reap massive profit in the Western world.

“They were taken advantage of,” says Owen Dean, the lawyer who won a settlement in 2006 for the heirs of Solomon Linda, a South African whose 1939 song “M’bube” was adapted into “The Lion Sleeps Tonight” and other variants.

A lawyer purporting to work for Linda’s heirs but actually representing Folkways Recordings, which had released “The Lion Sleeps Tonight” in the U.S., secured their assignation of copyright to his employer. “The daughters and the widow simply signed the documents unthinkingly, because they thought they were dealing with their own lawyer,” Dean said.

Blatant cases like this one have put many African musicians on their guard, according to Hugo Zemp, an ethnomusicologist at the University of Basel. Zemp has collected musical field recordings from around the world for decades, from Swiss farmers to Rajasthani villagers.

“The future of field research may be compromised,” wrote Zemp, “because now all musicians imagine that huge amounts of money can be made with any recording.” But the financial compensation gained in a few high-profile lawsuits belies the larger trend.

“The circulation of several thousand nonprofit ethnomusicological records is now directly linked to several million dollars worth of contemporary record sales, copyrights, royalty and ownership claims, many of them held by the largest music entertainment conglomerates in the world,” writes Steven Feld, a professor of anthropology and music at the University of New Mexico.

Feld’s research refers to appropriation via sampling. The digital era has made sampling exponentially simpler and thus more common, and a whole sector of intellectual property has sprung up around samples—one famous case involves the Verve, who because of an uncleared sample now pay 100 percent of royalties from their hit “Bittersweet Symphony” to the Rolling Stones.

But while samples are fiercely guarded in the U.S. and Europe, artists elsewhere usually lack IP lawyers to defend them. Hugo Zemp, in fact, unwittingly contributed to the commercial exploitation of a musical culture he’d hoped to protect.

In 1969, Hugo Zemp recorded a lullaby by the ‘Are’are people of the Solomon Islands. Twenty-two years later, a French producer approached him about sampling the track for a charity album to benefit Earth Day. The album, Deep Forest, was in fact a commercial enterprise which garnered a Grammy nomination, went double-platinum, and according to copyright lawyer Sherylle Mills, earned millions in profits for Sony Music from licensing songs to Porsche and Coca-Cola commercials.

Compensating the ‘Are’are singers would be an impossible task, according to Zemp—not only were the recordings made decades ago, but the individual singers were never identified. “Besides,” wrote Zemp, “who would finance the lawsuit?”

Martin Scherzinger, a professor at New York University, says that while lawsuits in the West concern ever smaller and more obscure samples, non-Western music often lacks copyright protection. “In 2010,” he said, “developing countries paid $8 billion more in royalties than they received. This equates to a massive transfer of wealth from the Global South to North.”

In the U.S. and most of Europe, performing rights organizations (PROs) such as BMI track the use of their members’ music and collect royalties from around the world. Whether a hit single in a Swiss car commercial or the muzak in a Mumbai waiting room, PROs collect royalty payments and distribute that money to performers and publishers.

While larger African economies like Nigeria, Kenya and South Africa do have functioning PROs, they often don’t have the infrastructure to account royalties around the globe. The South African Music Rights Organization (SAMRO), for example, was founded in 1961 with a modest roster of 40 South African composers. Today, the organization represents over 12,000 artists—still less than one percent of the membership of the American PROs. This imbalance leads to a one-way street of royalty payments. According to their annual reports, SAMRO has collected an average of approximately 7850 South African rand ($745 USD) per year since 2009 for plays of their members’ music in Europe and North America.

In the same period, BMI pulled in $300 million in foreign royalties, a “historic high in international income,” according to their 2013 annual report, because “timeless hits by Michael Jackson...and others remained some of the most-performed songs on international playlists.” While country-specific data is hard to come by, the structural imbalance is clear.

In smaller and less-developed countries, the lost opportunities are starker for musicians. In Sierra Leone, which in recent years has produced international acts like the Sierra Leone's Refugee All-Stars, and Janka Nabay and the Bubu Gang, there is no performing rights organization to collect or defend musical copyright. The country’s first musicians’ union, the Sierra Leone Association of Artists and Musicians (SLAAM) was formed in 2012.

To learn more about copyright issues in Africa and the global African diaspora, listen to our full episode, “The Money Show”.