Montreal is not only the home of the largest, and oldest running African music festivals in North America, Le Festival International Nuits d'Afrique (Read Afropop's coverage of this year's festival HERE), but many musicians from Africa are featured at the festival who are also now based in the city. We decided to sit down with some of them and find out, “Pourquoi Montreal?”

In speaking with the artists, often through a translator, it became clear that Montreal was often the city of choice for one obvious reason – the language. As former French colonies, the main spoken language in countries like Mali, Algeria, Senegal, and Côte d’Ivoire is still French. Moving to Francophone Quebec gives musicians an immediate advantage over moving to other countries like the United States where they would have a language barrier to contend with.

But each of the musicians we spoke to had their own immigrant tale to share.

"When you are obliged to go from your country and you didn't choose to go, it's very difficult,” says Algerian-born Karim Benzaid, who leads the band Syncop. Benzaid arrived in Montreal in 1998. His family first went into exile in Tunisia during the early 1990s where he spent his teenage years. Benzaid explains, “I started doing music in school. You see you have two options in Algeria – you can do either painting or music. So I chose music from the beginning, choral singing class, and when I went I started high school we started putting on parties and I'd sing.” It wasn't until he came to Montreal that he decided to pursue it professionally.

Syncop

“I was born in Côte d’Ivoire to Malian parents,” says Dakka, born Seïdou Dembélé, so he was already born in exile. When war broke out there in 2002, he fled to Mali. “I was a solo singer there, including playing at the French Cultural Center, which is a very prestigious venue in Bamako. And then I met a woman from Montreal, and that's what brought me here in 2007.”

Malian born kora player Diely Mori Tounkara also found his way to Montreal thanks to a woman from Quebec. “I had met a woman from Montreal, Estelle Lavoie, who was studying the kora. I was living in Senegal when we first met and she said, 'One day you must come and visit us,' and so I did,” he says with a smile. But it wasn't as simple as that. “Why did I leave Africa? I would say it's not you who chooses your destiny. When I was in Mali, I never thought I would go to Senegal.” Diely was teaching kora in Senegal at the time, but then returned to Mali in 2005 where he studied under Djeli Mady Tounkara, the lead guitarist of the Super Rail Band, “and not long after I was invited to play rhythm guitar with the Rail Band,” he says. Lavoie later came to Mali to continue her studies with Diely. “She encouraged me to come to Canada, but I didn't want to come and be an illegal. I wanted to do it right. I was doing well making a living in Mali doing nothing but playing music. When she returned home to Montreal, she wrote me a proper letter of invitation to join her musical group Taafé Fanga, and so I got a visa to come for six months. And then in 2008, I was invited back to join her again. And this time, I was able to get a work permit and stay on.”

Diely Mori Tounkara

William Atchouellou, whose stage name is Bobo, is also from Côte d’Ivoire, where he was a successful dancer and choreographer. When his wife was hired to be a dancer with Cirque du Soliel, he followed her on tour and they originally settled in the US, in Minneapolis-St. Paul, Minnesota. There, he taught African dance and drumming. “Then after that,” he says, “we decided to come to Montreal. We moved here in 2007 and my wife is still touring with the Cirque. She does African dance in the show called Dralion.”

Algerian Karim Saada moved to Montreal way back in 1988. “I didn't come here as an artist, I just came to live here. At the time I arrived, I didn't think about doing music as I am now. I thought I'd just be working, as back home. I came directly to the Quebec because first, of course, for the language. But I was also avoiding all the racism in Europe because in the late 80s it was really bad. At that time in France, you'd see signs at bars and clubs: 'No dogs, No Arabs, No Blacks.'”

For Congo-born Joyce N'Sana, the youngest of those we spoke with, she began singing at an early age, in her father's church. Her parents sent her to France as she had other family members and friends there, and it was there she first began singing professionally. Then, in 2009, she moved to Quebec to get a degree in childhood education, which she continues to pursue along with her musical career. “Moving here,” she says, “was an opportunity to get out of both Africa and France and see more of the world.”

De Gaulle-Ismail Ufiteyezu, better known as Maréchal De Gaulle, is from Rwanda, and achieved international success in the 1980s, both as a solo artist and within groups including Les Huit Anges and The Ingeli Band. De Gaulle continued to base himself in Rwanda, even through the genocide of the 1990s. “I arrived on June 23, 2009,” he says. “It's a date I could never forget. It was a dream come true for me to come to Canada. I was on tour with a traditional dancing group for two months in the United States, led by Jean-Paul Samputu. I had family and friends living here already, and Jean-Paul was also based in Canada. So I left, not because of the troubles, the country was doing better and there was peace and security, but it was only because I wanted to be better at my music and Jean-Paul told me that Canada was a good place to become a better known musician and artist.”

But being a stranger in a strange land has both its positive and negative sides, as the artists shared with us.

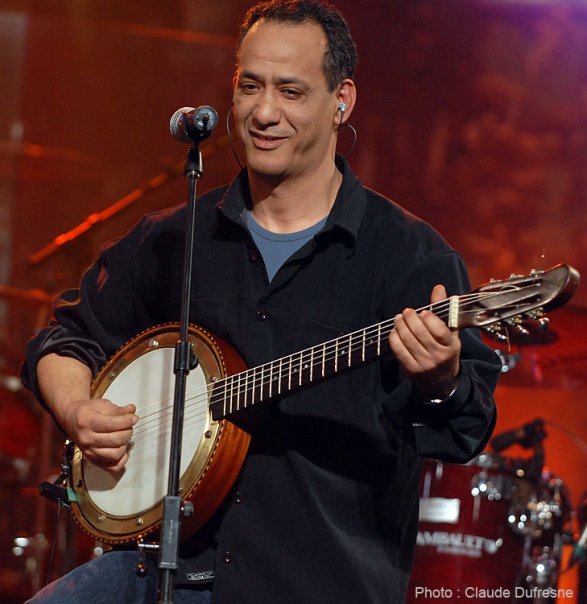

“The first thing that really surprised me here in Montreal,” explains Karim Saada, “was since I knew there was so much racism in Europe, I was kind of expecting the same thing here. But when I got here I realized how much more open-minded people are here in Canada. My wife is from Quebec, and we are really welcomed here. As far as the music, I wasn't expecting to play my music here in Canada. I was so excited, I had my friends send me my banjo from Algeria to play here and it's great.

“I wrote a song about my immigrant experience, it's called the Dance of the Exile,” Saada continues. “It talks about being an immigrant, how half of yourself is in your new country, but you still have part of your heart in your old country. You can never be completely one place. In the song, I sing that I came here because I had to avoid my country, where brothers were becoming enemies, especially during the 90s in Algeria.” That album, entitled the same as the song, earned Saada a Juno award nomination (the Canadian equivalent of a Grammy) in 2010.

Karim Saada

Bobo, as all the artists said when they first arrived, was impressed with the musical diversity of the city. “I was really surprised seeing the people here playing djembe and doing African dance,” he says. “When I first visited in 2003, I saw people playing Afrobeat, because they like Fela, and I was like, 'Wow! Montreal is a really, really good place.' I was really excited to come live here.” Then he adds, “The winters are cold and a lot of snow. But if you can live in Minnesota, you can live here. I'm used to that now.”

“It was also a great surprise for me to find so many Africans from different traditions I could learn from, and it's a very rich resource. Learning is a big thing for me here in Montreal,” says Dakka. “I learn something every day. You never stop learning. I've learned so much since I've been here. But at the same time, you never forget your parents and your obligations to them. Part is me is with them, but I know I live here now. It's a complicated life. You have to work, keep your art going, and keep your connections with home. And it's a kind of stress I've never known before, but I'm doing it.”

“The hardest part,” Dakka adds, “is that I'm not known to audiences so I don't have much financial support for my arts, which means I have to play in bars night after night, sometimes they're empty, and you really have to go out there and meet people and make all the connections yourself.”

Most of the musicians we spoke to are still unable to support themselves full time playing. Dakka, for instance, is a cobbler and has a shoe shop in the heart of the city. Karim Benzaid has a job with the government, working with new immigrants helping them to navigate and integrate into the city. Bobo is currently employed at a metal manufacturing plant as a machine operator to help pay for the recording of his first album.

“Because you don't have outside support as back home, you have to pay everything by yourself – the musicians, the technicians,” explains Maréchal De Gaulle who often picks up work as a DJ and other gigs to supplement his income. “If you want to travel or tour the country – and this is a really big country – you have pay your tickets by your own self. So it can be difficult. But back home it's a small country, so it's not as expensive as being here.”

According to a recent article in the Montreal Gazette, “[U]nemployment among university-educated Montreal immigrants age 35-44 was 11.3 per cent in 2011, compared to 2.6 per cent for the university-educated, native-born population in that age group.” And it's undeniable that while all the musicians acknowledge that Montreal is a very welcoming and open-minded city, there is still some racism or nationalism to contend with.

“When I first arrived,” recalls Joyce N'Sana, “I wasn't in Montreal. I was in a country town just outside the city where the school was, and there was a lot less mixing there. I had a little problem in the beginning with the accent here in Quebec, because it's so different than how they speak French in France. People used to give me looks because of both my accent and that I'm black.”

“Look, in all cities there are problems of racism,” explains Karim Benzaid, “but when people come to my shows, they come to have fun, to be happy. But I know some communities and some immigrants have big difficulties finding jobs. And this is a problem in general in Montreal and Quebec, and the whole world right now. So I'm not saying that everything is beautiful or that this is paradise. Some people are unhappy and other people are very happy. It depends on the person.”

On this subject, Diely Mori Tounkara probably best sums it up. “Certainly, I don't feel at home here sometimes, but that's normal. When you decide to leave your country, you're basically leaving your house to live outside your home, and there will be all those things that will bother you. You may go outside and see people who don't want to see you.

“As an analogy,” he continues, “I have five fingers on my hand. The five fingers are all different. They may be all part of the same hand, but they will stay different. Nothing is going to change that. That's just the way they are. So not everyone is going to like you. But things will come easier in time when you realize that and stop expecting everyone to like you. You are now at ease, because you've accepted that. When an African is walking down the street and they see a white person coming towards you, you'll notice the white person may cross the street to the other side. But the same thing happens in Africa. There are a lot of Africans who don't like white people. It's everywhere. We're not the same and you have to accept it. That's life. Not everyone's going to like you.” He then adds, laughing, “And then, of course, there are people who want to see me all the time.”

As already noted, the musical diversity of the city has been very inspiring to these immigrant artists. Because there is such a mix of musicians working in Montreal from, not just Africa, but from the world over, these artists are having an opportunity to not just hear, but also to blend in musical styles, beats, rhythms, and influences and are creating a unique and new form of world music like no where else.

“Montreal is like the capital of mixing,” says Joyce N'Sana, “because you find people from everywhere in the world here. And this mix is very reflected in the music. I like that because I can use that to create some music from all this mix which is unique that people can appreciate, because it will be the first time they hear anything like it. I try to take a little bit of everything I hear here to mix in my music to make it more versatile. I touched some reggae in France when I was there, but because there is a big Jamaican community, that is really where I am musically. Right now, I am working on my first album and it will be a mix of styles, which I hope will be done this year.”

Joyce N'Sana

Bobo, as well, is finding the reggae scene in Montreal to be highly influential to his music. “Lately, I'm going kind of towards reggae because for me it's the music that really allows me to express myself. I can talk about a lot of stuff going on right now in the world, especially the politics of the world,” he notes. “I always feel that playing with other musicians from other places adds some creativity in what I'm doing. I don't want my music to be just Ivorian music. I want it to be music that's pretty much open to everybody. So playing with musicians from Cameroon is good because he'll add his experience, or musicians from Canada which is also good because they have the European/North American flavor to add. So I really love it. I really want my music to be international.”

“My dream in moving here was to come and work with other people and develop my own world music,” concurs Maréchal De Gaulle. “It's like taking the traditional music from my place and then adding things from other places to make it more modern and be able to spread it to the world. It's all about taking things from West & East Africa, the Caribbean, Asia, from everywhere, and then blending it with the music from my country to make something that really is a blend from everywhere. I'm now working on something for next year which will be a blend of all the influences I've had here.”

Karim Benzaid often works and performs with Mexican-Paraguayan-Canadian musician Boogat. “We did this song together called Cumbia de las Luchas. I sing in Algerian and he sings in Spanish,” he explains. “And we will work together again on the next Syncop CD. He also worked with me doing the rhythm programming for my last CD, on the song Cosmopolitisme. You can hear the Latin percussion sound. We had a very good time doing that.”

“I've definitely been influenced by the music I hear here,” adds Karim Saada. “By learning all these difference types of music, now I'm doing my own modern chaabi by mixing it all together.”

“The strength of Montreal is the whole idea of the mixing,” concludes Djeli Mady Tounkara. “When I leave here I'm an African, or a Malian, but when I come back to Montreal I feel like everyone is one. If I see someone from anywhere in Africa, I immediately feel like they are my brothers, it's like a fraternity. You don't think about differences, you think about unity, you think about being part of a community. That's just something in the chemistry of the city that I appreciate.... If in the future someplace else calls to me, I will move there. But for now, here in Montreal, I have peace. And where you have peace, that's where you have to live.”

“This is home for me, for sure,” smiles Maréchal de Gaulle, and then proclaims, “Viva la Canada!”