Blog February 25, 2013

Afro-Mexico Road Trip #1: Introducing Afro-Mexico

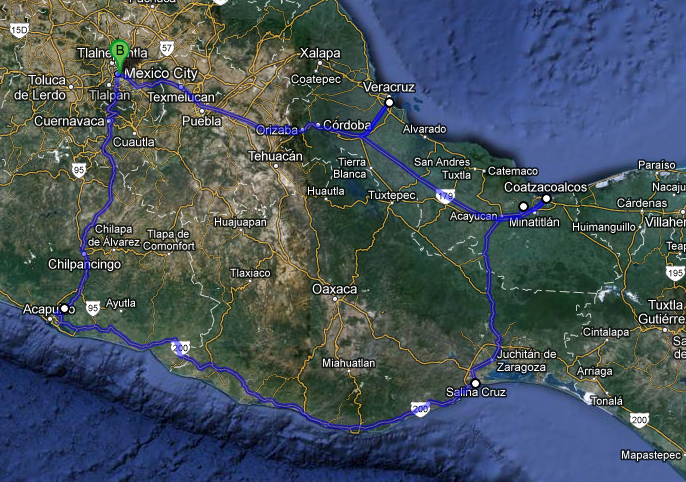

In early January, I went to Mexico to do research for an upcoming Afropop “Hip Deep” radio documentary exploring the African heritage in music in Mexico, Afropop’s first ever Mexico-focused project. I was joined by filmmaker Nina Macintosh, to make a series of short videos on the topic as well. Against all the advice of friends and family both in Mexico and the US, we rented a puttering old car and drove around the country, tracing Afro-Mexican music and history.

First, we came down the mountains from Mexico City, and visited the Costa Chica in Guerrero state, where criollo communities play traditional chilena and a high-energy, not-so-traditional form of cumbia. From there we curved down the coast and crossed the country at it’s narrowest point, visiting the towns in southern Veracruz where the Afro-Mexican influenced son jarocho is experiencing a serious youth revival. Then we drove up to Veracruz city, whose port facilitated the spread of Afro-Cuban music in Mexico. Last, we went back up the mountains to Mexico City, to visit the old-school dancehalls where super cool old people still boogey to the Afro-Cuban danzón.

Researching Afro-Mexican culture is very different than researching other African-descended musical traditions in Latin American because it’s still very much uncertain what Afro-Mexican even means. Here are the facts: according to colonial records, over 100,000 enslaved Africans were brought to Mexico in the 16th and 17th centuries. By 1793, census figures put Afro-Mexicans at 10 percent of Mexico’s population - 370,000 people. Some of the earliest Mexican military heroes had African heritage, including Vicente Guerrero, who served as president, and revolutionary leader José Morelos.

In the world beyond the facts, in the world of everyday life in Mexico, the world of people’s identities, the term “Afro-Mexican” is much less clear. In most cases, African ancestry has been blended completely with indigenous and European ancestry. For a long time, Mexican ideologues espoused the notion of a “raza cosmica” (“cosmic race”) based on the mixture indigenous and European blood, and that mestizo notion of self is a huge part of national identity in Mexico. Africa, the so-called “third root,” never really figured into the conversation.

[caption id="attachment_7306" align="alignleft" width="286"] Benigno Gallardo, leader in the Guerrero teacher union and Afro-Mexican activist.[/caption]

In recent years, all of a sudden, a lot of people are talking about Afro-Mexico. There have been scholarly works and museum exhibits in both the US and Mexico, and political organizations have begun to spring up. There have been efforts to count self-identified Afro-Mexicans in order to push for the national recognition that could facilitate much-needed funding for cultural initiatives. There have been radio programs and documentaries. Many have seen these projects as a way to recapture a forgotten history, to give voice to a group that has been historically voiceless.

[caption id="attachment_7307" align="alignright" width="384"]

Benigno Gallardo, leader in the Guerrero teacher union and Afro-Mexican activist.[/caption]

In recent years, all of a sudden, a lot of people are talking about Afro-Mexico. There have been scholarly works and museum exhibits in both the US and Mexico, and political organizations have begun to spring up. There have been efforts to count self-identified Afro-Mexicans in order to push for the national recognition that could facilitate much-needed funding for cultural initiatives. There have been radio programs and documentaries. Many have seen these projects as a way to recapture a forgotten history, to give voice to a group that has been historically voiceless.

[caption id="attachment_7307" align="alignright" width="384"] Eduardo Añorve, journalist, poet, and Afro-Mexican researcher from Cuajinicuilapa, Guerrero.[/caption]

Others are more skeptical. Some have said that the concept of “Afro-Mexican” was invented by U.S. scholarship, an attempt to impose American racial ideas on Mexico. Or that that it was nurtured by Chicano activists interested finding a racial basis for political solidarity with African-Americans. People in Mexico, outside of well-heeled hippies and academics, are often uneasy talking about black heritage. There have been arguments about terminology – should it be afromestizo, afromexicano or plain afrodecendiente? One cultural activist I met in the Costa Chica insisted that his culture wasn’t “Afro-Mexican” – he preferred the idea of being criolla, or creole. And while son jarocho groups in the U.S. often tout their music’s Afro-Mexican origins, members influential jarocho groups from Veracruz like Los Cojolites will smile wryly when you ask about the African roots of their music and say, “that’s what they tell us.” It’s part of their understanding of the music, but just one part in a big, complicated cultural web.

Eduardo Añorve, journalist, poet, and Afro-Mexican researcher from Cuajinicuilapa, Guerrero.[/caption]

Others are more skeptical. Some have said that the concept of “Afro-Mexican” was invented by U.S. scholarship, an attempt to impose American racial ideas on Mexico. Or that that it was nurtured by Chicano activists interested finding a racial basis for political solidarity with African-Americans. People in Mexico, outside of well-heeled hippies and academics, are often uneasy talking about black heritage. There have been arguments about terminology – should it be afromestizo, afromexicano or plain afrodecendiente? One cultural activist I met in the Costa Chica insisted that his culture wasn’t “Afro-Mexican” – he preferred the idea of being criolla, or creole. And while son jarocho groups in the U.S. often tout their music’s Afro-Mexican origins, members influential jarocho groups from Veracruz like Los Cojolites will smile wryly when you ask about the African roots of their music and say, “that’s what they tell us.” It’s part of their understanding of the music, but just one part in a big, complicated cultural web.

So here’s the point: it’s complicated. It’s political. Identity always is. But through this project, we’ve had the opportunity to explore that complexity through one of the best tools we have: music. That’s been the mission of our Hip Deep programming since the beginning, to explore the murky soup of history and culture while keeping ourselves dancing at the same time.

Stay tuned for more!

All photos by Nina Macintosh.

So here’s the point: it’s complicated. It’s political. Identity always is. But through this project, we’ve had the opportunity to explore that complexity through one of the best tools we have: music. That’s been the mission of our Hip Deep programming since the beginning, to explore the murky soup of history and culture while keeping ourselves dancing at the same time.

Stay tuned for more!

All photos by Nina Macintosh.

Benigno Gallardo, leader in the Guerrero teacher union and Afro-Mexican activist.[/caption]

In recent years, all of a sudden, a lot of people are talking about Afro-Mexico. There have been scholarly works and museum exhibits in both the US and Mexico, and political organizations have begun to spring up. There have been efforts to count self-identified Afro-Mexicans in order to push for the national recognition that could facilitate much-needed funding for cultural initiatives. There have been radio programs and documentaries. Many have seen these projects as a way to recapture a forgotten history, to give voice to a group that has been historically voiceless.

[caption id="attachment_7307" align="alignright" width="384"]

Benigno Gallardo, leader in the Guerrero teacher union and Afro-Mexican activist.[/caption]

In recent years, all of a sudden, a lot of people are talking about Afro-Mexico. There have been scholarly works and museum exhibits in both the US and Mexico, and political organizations have begun to spring up. There have been efforts to count self-identified Afro-Mexicans in order to push for the national recognition that could facilitate much-needed funding for cultural initiatives. There have been radio programs and documentaries. Many have seen these projects as a way to recapture a forgotten history, to give voice to a group that has been historically voiceless.

[caption id="attachment_7307" align="alignright" width="384"] Eduardo Añorve, journalist, poet, and Afro-Mexican researcher from Cuajinicuilapa, Guerrero.[/caption]

Others are more skeptical. Some have said that the concept of “Afro-Mexican” was invented by U.S. scholarship, an attempt to impose American racial ideas on Mexico. Or that that it was nurtured by Chicano activists interested finding a racial basis for political solidarity with African-Americans. People in Mexico, outside of well-heeled hippies and academics, are often uneasy talking about black heritage. There have been arguments about terminology – should it be afromestizo, afromexicano or plain afrodecendiente? One cultural activist I met in the Costa Chica insisted that his culture wasn’t “Afro-Mexican” – he preferred the idea of being criolla, or creole. And while son jarocho groups in the U.S. often tout their music’s Afro-Mexican origins, members influential jarocho groups from Veracruz like Los Cojolites will smile wryly when you ask about the African roots of their music and say, “that’s what they tell us.” It’s part of their understanding of the music, but just one part in a big, complicated cultural web.

Eduardo Añorve, journalist, poet, and Afro-Mexican researcher from Cuajinicuilapa, Guerrero.[/caption]

Others are more skeptical. Some have said that the concept of “Afro-Mexican” was invented by U.S. scholarship, an attempt to impose American racial ideas on Mexico. Or that that it was nurtured by Chicano activists interested finding a racial basis for political solidarity with African-Americans. People in Mexico, outside of well-heeled hippies and academics, are often uneasy talking about black heritage. There have been arguments about terminology – should it be afromestizo, afromexicano or plain afrodecendiente? One cultural activist I met in the Costa Chica insisted that his culture wasn’t “Afro-Mexican” – he preferred the idea of being criolla, or creole. And while son jarocho groups in the U.S. often tout their music’s Afro-Mexican origins, members influential jarocho groups from Veracruz like Los Cojolites will smile wryly when you ask about the African roots of their music and say, “that’s what they tell us.” It’s part of their understanding of the music, but just one part in a big, complicated cultural web.

So here’s the point: it’s complicated. It’s political. Identity always is. But through this project, we’ve had the opportunity to explore that complexity through one of the best tools we have: music. That’s been the mission of our Hip Deep programming since the beginning, to explore the murky soup of history and culture while keeping ourselves dancing at the same time.

Stay tuned for more!

All photos by Nina Macintosh.

So here’s the point: it’s complicated. It’s political. Identity always is. But through this project, we’ve had the opportunity to explore that complexity through one of the best tools we have: music. That’s been the mission of our Hip Deep programming since the beginning, to explore the murky soup of history and culture while keeping ourselves dancing at the same time.

Stay tuned for more!

All photos by Nina Macintosh.