Blog February 25, 2013

Afro-Mexico Road Trip #2: The Chilena

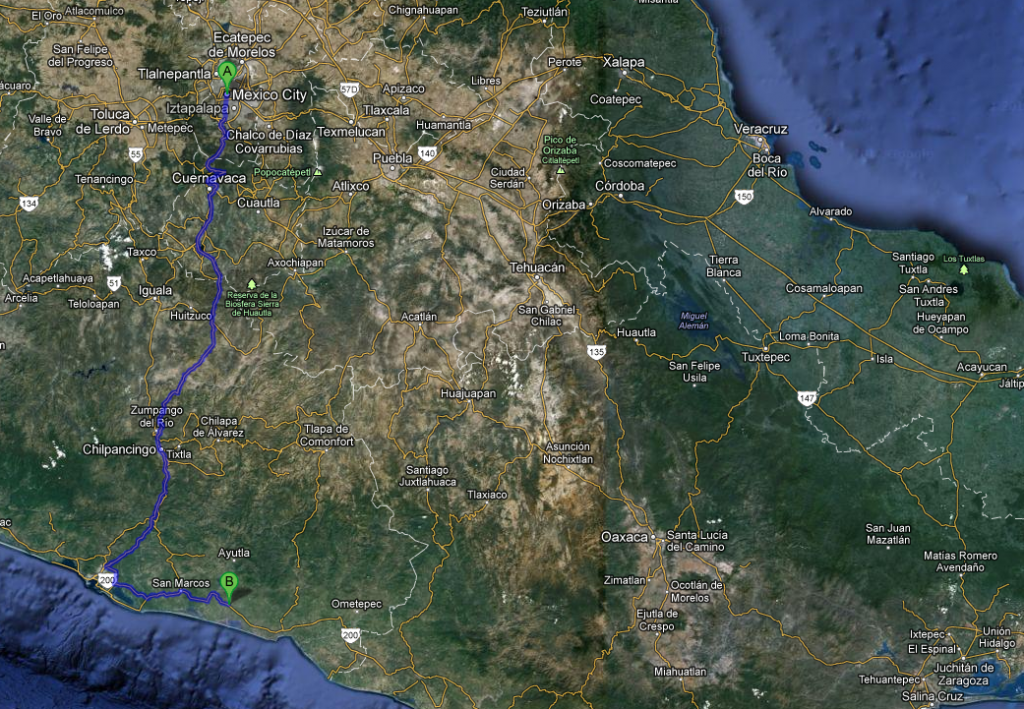

Afropop Producers Marlon Bishop and Nina Macintosh spent two weeks driving around Mexico in search of Afro-Mexican musical heritage, in research for an epic Afropop “Hip Deep” radio documentary on the subject. We’re posting missives from their journey here. To read more posts from the Afro-Mexico Roadtrip series, click here.

Cruz Grande, Guerrero

First stop on our trip was the Costa Chica, a region of Mexico’s Pacific coast known for having the largest Afro-Mexican presence in the country. It’s made of up of a string of towns on an isolated and largely impoverished stretch between the beach resorts of Acapulco and Puerto Escondido. Although the changing racial politics of Mexico (more on that to come in later blogs hereabouts) have led some in the region to identify as “Afro-Mexican” or “Afro-Mestizo,” the most common way for costeños to refer to their culture is criollo, or creole.

One of those towns is Cruz Grande, a phenomenally relaxed little place gathered around a handsome blue church. We came here to speak with Los Gallardo, a family of musicians who have been maintaining criollo musical traditions for generations. Most important among them is the chilena, also known as the son de artesa, a bouncy sound in 6/8 time, played on any number of string instruments including the harp and the guitar-like vihuela. Most Mexican folk styles are light on percussion, but the chilena keeps time with a little wooden box hit with a wooden block, known as the caja de tapeo.

[caption id="attachment_7345" align="aligncenter" width="448"] Eulalio is one of the last chilena harpists remaining on all of the Costa Chica[/caption]

Once upon a time, chilena was the party sound of the coast. Dancers would give an rhythmic accompaniment by dancing on a long, rectangular platform known as the artesa, a tradition rumored to have been started by fisherman who danced on top of turned-over canoes for nighttime festivities. Whether that story is true or not, the artesa doesn’t appear at parties any longer, banished to the realm of folkloric dance performances. In fact, the chilena itself is barely played on the Coast these days either. With no economy to support it, only a handful of musicians keep it alive out of love for the tradition.

Eulalio Gallardo is one of them, and it runs in the family. His grandfather was a beloved local musician. His father, also named Eulalio Gallardo, was one of the great musicians of the coast in the mid-20th century, and wrote many well-known songs of the region. He has a band with five of his brothers called Los Gallardo, but these days, he more often plays music with his teenage sons: at church, at weddings, wherever they’re needed. To be a Gallardo means to play music. “Before my father died, rest in peace, he asked me to teach this music to my sons,” says Eulalio. “Even if we have to work doing other things to survive, we have musician’s hearts, and we’re going to continue to nurture and conserve this.”

Eulalio is a pretty tremendous musician – in the short time we hung out out, I saw him play an extremely mean harp, guitar, vihuela, and guitarron, not to mention that he sings in a rich baritone. Since there is no support, government or otherwise, for the traditional coastal music, he lives off mariachi gigs and renting out a small speaker system for parties. His wife brings in extra funds making chilate, a local drink made out of rice, chocolate, and cinnamon.

Eulalio is one of the last chilena harpists remaining on all of the Costa Chica[/caption]

Once upon a time, chilena was the party sound of the coast. Dancers would give an rhythmic accompaniment by dancing on a long, rectangular platform known as the artesa, a tradition rumored to have been started by fisherman who danced on top of turned-over canoes for nighttime festivities. Whether that story is true or not, the artesa doesn’t appear at parties any longer, banished to the realm of folkloric dance performances. In fact, the chilena itself is barely played on the Coast these days either. With no economy to support it, only a handful of musicians keep it alive out of love for the tradition.

Eulalio Gallardo is one of them, and it runs in the family. His grandfather was a beloved local musician. His father, also named Eulalio Gallardo, was one of the great musicians of the coast in the mid-20th century, and wrote many well-known songs of the region. He has a band with five of his brothers called Los Gallardo, but these days, he more often plays music with his teenage sons: at church, at weddings, wherever they’re needed. To be a Gallardo means to play music. “Before my father died, rest in peace, he asked me to teach this music to my sons,” says Eulalio. “Even if we have to work doing other things to survive, we have musician’s hearts, and we’re going to continue to nurture and conserve this.”

Eulalio is a pretty tremendous musician – in the short time we hung out out, I saw him play an extremely mean harp, guitar, vihuela, and guitarron, not to mention that he sings in a rich baritone. Since there is no support, government or otherwise, for the traditional coastal music, he lives off mariachi gigs and renting out a small speaker system for parties. His wife brings in extra funds making chilate, a local drink made out of rice, chocolate, and cinnamon.

Eulalio is one of the last chilena harpists remaining on all of the Costa Chica[/caption]

Once upon a time, chilena was the party sound of the coast. Dancers would give an rhythmic accompaniment by dancing on a long, rectangular platform known as the artesa, a tradition rumored to have been started by fisherman who danced on top of turned-over canoes for nighttime festivities. Whether that story is true or not, the artesa doesn’t appear at parties any longer, banished to the realm of folkloric dance performances. In fact, the chilena itself is barely played on the Coast these days either. With no economy to support it, only a handful of musicians keep it alive out of love for the tradition.

Eulalio Gallardo is one of them, and it runs in the family. His grandfather was a beloved local musician. His father, also named Eulalio Gallardo, was one of the great musicians of the coast in the mid-20th century, and wrote many well-known songs of the region. He has a band with five of his brothers called Los Gallardo, but these days, he more often plays music with his teenage sons: at church, at weddings, wherever they’re needed. To be a Gallardo means to play music. “Before my father died, rest in peace, he asked me to teach this music to my sons,” says Eulalio. “Even if we have to work doing other things to survive, we have musician’s hearts, and we’re going to continue to nurture and conserve this.”

Eulalio is a pretty tremendous musician – in the short time we hung out out, I saw him play an extremely mean harp, guitar, vihuela, and guitarron, not to mention that he sings in a rich baritone. Since there is no support, government or otherwise, for the traditional coastal music, he lives off mariachi gigs and renting out a small speaker system for parties. His wife brings in extra funds making chilate, a local drink made out of rice, chocolate, and cinnamon.

Eulalio is one of the last chilena harpists remaining on all of the Costa Chica[/caption]

Once upon a time, chilena was the party sound of the coast. Dancers would give an rhythmic accompaniment by dancing on a long, rectangular platform known as the artesa, a tradition rumored to have been started by fisherman who danced on top of turned-over canoes for nighttime festivities. Whether that story is true or not, the artesa doesn’t appear at parties any longer, banished to the realm of folkloric dance performances. In fact, the chilena itself is barely played on the Coast these days either. With no economy to support it, only a handful of musicians keep it alive out of love for the tradition.

Eulalio Gallardo is one of them, and it runs in the family. His grandfather was a beloved local musician. His father, also named Eulalio Gallardo, was one of the great musicians of the coast in the mid-20th century, and wrote many well-known songs of the region. He has a band with five of his brothers called Los Gallardo, but these days, he more often plays music with his teenage sons: at church, at weddings, wherever they’re needed. To be a Gallardo means to play music. “Before my father died, rest in peace, he asked me to teach this music to my sons,” says Eulalio. “Even if we have to work doing other things to survive, we have musician’s hearts, and we’re going to continue to nurture and conserve this.”

Eulalio is a pretty tremendous musician – in the short time we hung out out, I saw him play an extremely mean harp, guitar, vihuela, and guitarron, not to mention that he sings in a rich baritone. Since there is no support, government or otherwise, for the traditional coastal music, he lives off mariachi gigs and renting out a small speaker system for parties. His wife brings in extra funds making chilate, a local drink made out of rice, chocolate, and cinnamon.