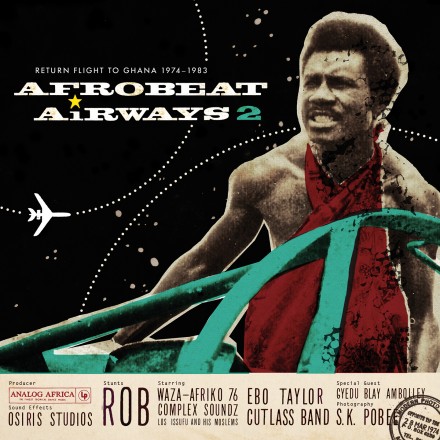

Fela Kuti will probably always be the figure most closely associated with the Afrobeat genre, and for good reason. He did after all coin the term. However the coining took place not in Fela’s native Nigeria, but rather in Ghana. While visiting Ghana in 1968, Fela was inspired by the music scene, which at the time was both livelier and funkier than that of Nigeria. In fact the liner notes for Afrobeat Airways 2: Return Flight To Ghana 1974-1983 quote him as saying, after watching what was going on in Ghana, “I knew I had to get my shit together. And quick!” The music compiled on Afrobeat Airways 2 comes from the decade after Fela’s visit, but it nevertheless provides ample evidence of what pushed Fela toward the innovations he became known for.

During Ghana’s musical heyday in the '70s, nightclubs were packed every night of the week with groups playing in genres as diverse as highlife, funk, soul, Latin music, reggae, and of course, Afrobeat. In Ghana, Afrobeat, though inspired by Fela’s experience there, was not as popular as highlife, but the Ghanaian bands who played in this style were every bit as good as groups in Nigeria, at least in terms of musicianship. Politically, few groups attempted to engage audiences with the type of messages that Fela laced his music with. One exception is the Cutlass Band, whose song on the compilation, “Obiara Wondo” does attempt to combine music and politics. The group’s leader Isaac Kwasi Anin was a farmer, and the band itself was named after the blade he used to farm. “Obiara Wondo” urges the Ghanaian people to “farm and eat,” a message perhaps less controversial than those of Fela, but still political enough to ensure it didn’t receive much success in Ghana where political songs did not sell during this period.

The most recognizable artist featured on Afrobeat Airways 2 is Ebo Taylor, whose previously unreleased track “Children Don’t Cry” was recorded circa 1983. For more on Taylor, check out our Hip Deep program Ghana 1: Ebo Taylor and the Pioneers of Afro-Funk. However, it is some of the lesser known musicians whose tracks really stand out as gems on the compilation. The little known De Frank, who was born in Togo and played for K. Frimpong (whose track “Abrabo” is also on the compilation) in his Cubanos Fiestas, contributes two outstanding tracks as a bandleader. The first is “Do Your Own Thing,” credited to De Frank’s Band. On the song, De Frank sing-speaks over some very funky organ playing, “I believe in Afro music as people do believe in funk.”

[soundcloud url="https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/105380228" width="100%" height="166" iframe="true" /]

“Waiting For My Baby,” performed by De Frank & His Professionals, is a joyous horn-laden track, in which De Frank sings, “Waiting for my baby/Oh, groovy/So I can dance.” The song instantly escorts its listeners to the golden age of Ghanaian nightlife, full of dancing and, of course, great music.

Another highlight is “Gbei Kpakpa Hife Sika” by Waza-Afriko 76. As so many different musical traditions interacted with one another in 1970s Ghana, very little should be unexpected on a release from this time period. Yet the soulful harmonica that kicks in halfway through this track comes out of nowhere and makes this one of the truly unique tracks of the Afrobeat canon.

Tony Sarfo & The Funky Afrosibi’s wah-wah filled heater “I Beg” is one of Afrobeat Airways 2’s best songs and it lays claim to the best back story as well. Sarfo recalls in the liner notes that in a dream “a man taller than a coconut tree took me to a slum where people were playing music - people with the heads of lions and giraffes and multicolored light bulbs dressing their arms. They were supernatural bodies… The next morning, I saw a small bird with feathers the same colour of those light bulbs and the composition for “I Beg” came to me. I had had a few drinks the night before, but not much.”

The scene documented on Afrobeat Airways 2 fell apart by the end of the '70s. The political climate had changed in Ghana, with coups and urban curfews making the type of nightlife that had spawned so many talented musicians no longer possible. Most of those musicians left Ghana for other countries in Africa, as well as Europe and the United States. The introduction of digital equipment and computer software also changed the dynamic of the Ghanaian music scene, ushering in more electronic styles that many of Ghana’s veteran musicians continue to resent. Tony Sarfo also cites piracy as a cause for the scene’s decline, but he clarifies in the liner notes, “Piracy aside, the music really died because we lost our best musicians. And when they died, every musician, the entire community - and the entire country - wept. They wept!” Sammy Cropper, a guitarist, who played with both K. Frimpong and Pierre Antoine & Vis A Vis, whose song “Say Min Sy Soh” is featured on the compilation, currently works as a security guard for an all-girl’s vocational school. He says in the liner notes, “Today, the hiplife music style that all the youngsters love - it’s weak. It killed - and continues to kill - any highlife music that remains. To be honest, you’ve caught me off-guard with your visit and I wish I could remember more but I just can’t. I’m truly surprised that my music - and Ghanaian music of the ‘70s - is traveling as much as it is.” While the music on Afrobeat Airways 2 is worth treasuring on its own, the compilation also serves as an important document of a once-thriving musical moment that deserves to be remembered.