Our first report left off as the first annual Festival Acoustik de Mali was wrapping up in Bamako, and we (Sean Barlow and Banning Eyre) were bidding farewell to the fellow journalists and artists who took part in that historic event. (Here’s a link to Part One.) From there, it was on to a rich set of interviews and performances in more hidden corners of Bamako, and to the Festival Sur le Niger in Ségou. What follows is a whirlwind tour of our second music-packed week in Mali.

Statue of Ali Farka Toure in Bamako

Our main focus on this trip has been research for two forthcoming Hip Deep programs, one focusing on Tuareg music and history and another on musical life in Bamako in the wake of “the crisis” of 2012-13. We headed to Ségou with our field assistant Hamidou to attend the 12th edition of the Festival Sur le Niger and, in particular, to cover the first performance of the 2016 Caravane Culturelle Pour la Paix. The Caravan is a collaboration between the Ségou festival, Morocco’s Taragalte Festival, and the legendary Festival in the Desert, now in exile from its traditional home in the Timbuktu region. This year’s Caravan showcases acts from the Malian north and Morocco, including two leading Tuareg acts.

Tartit

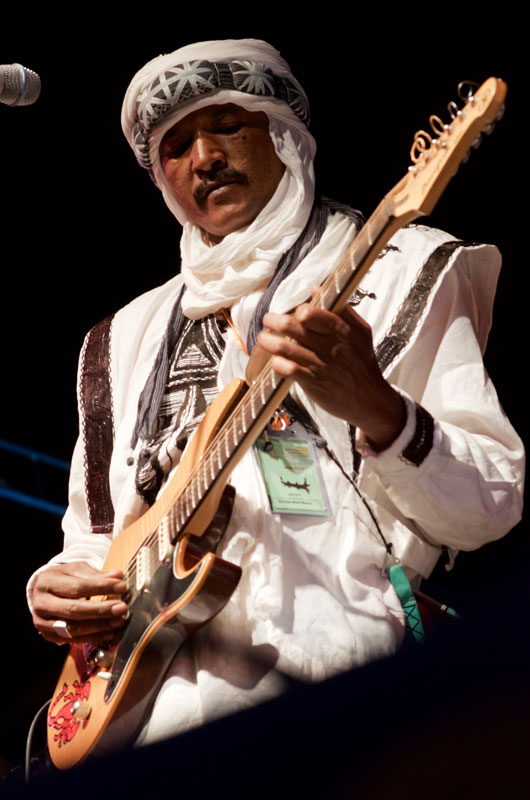

As the name suggests, the Festival Sur le Niger takes place on the banks of the graceful Niger River about three hours drive north of Bamako. The festival’s trademark attraction has been large-scale nighttime concerts staged on a floating barge with a boisterous crowd of revelers gathered along the river bank. In the past, Segouviens have enjoyed top Malian acts such as Salif Keita, Fatoumata Diawara, Habib Koite and Bassekou Kouyate’s Ngoni Ba. This year, unfortunately, the government and festival organizers felt they could not provide adequate security in such an open public location, so these big concerts were canceled. Instead, there were three nighttime concerts in the more enclosed Festival Village: an evening jam session organized by Malian maestro Cheikh Tidiane Seck (Thursday), the Caravan concert followed by a set from Sikasso bandleader Abdoulaye Diabaté (Friday), and a night of Malian hip-hop with Master Soumy, Mylmo, Gaspy and others (Saturday). There were also theater performances, daytime concerts, art expositions and seminars—notably one on the problems in the north and the road to lasting peace in Mali. All terrific stuff, well attended by locals and a small group of foreign journalists.

Samba Toure

We caught some of the daytime action on Friday, the Caravan concert that night, the seminar on the North the next morning, and a chance to catch up with some top Malian rappers before heading back to Bamako on Saturday. This year’s Caravan featured Tuareg groups Amanar and Tartit, a multigenerational Moroccan roots-pop ensemble called Chamra du Chamra, and guests, including Ali Farka Toure protégé Samba Toure. (The Bamako concert, we learned, would also include Khaira Arby’s band, and other guests would join locally during the Caravan’s 10-day tour through southern Mali.) At Ségou, before the individual acts took the stage, a collaborative Caravan band played a short lively set emphasizing regional unity, with Tuareg, Songhai, Dogon, Bambara and other artists jamming together. A Tuareg song sung by Ahmed ag Kaedi of Amanar, laced with intricate Songhai guitar work from Samba Toure, epitomized the idea of Malian ethnic harmony quite beautifully.

Tartit

It was a thrill to see Tartit perform again. This mostly female Tuareg ensemble from Timbuktu mesmerized the crowd with hypnotic trance songs and elegant, seated takamba arm-and-hand dancing. We were pleased and reassured to see an audience of mostly Bambara teenagers and 20-somethings joining in delightedly. Music truly did seem to transcend the tensions of recent years. If resentments against the Tuareg as the catalyst for the crisis linger, there was no sign of it here. Sets by Tartit and Chamra du Chamra followed a similar flow—first a seated, traditional performance, followed by modern songs featuring guitar accompaniment. After these, Amanar delivered a short punchy set of Tuareg rock. Ahmed ag Kaedi told us that the mark of his group was to pump the grooves in an effort to reach and excite a younger audience. That was clearly working here.

Abdoulaye Diabaté

The consummate showman, griot and bandleader Abdoulaye Diabaté (not to be confused with Abdoulaye “Djoss” Diabaté in NYC) led his group through a lengthy, rip-roaring set to finish out the night. Diabaté is a majestic figure on stage, and he began his set booming out ceremonial praise for the people of Ségou. Once the grooves kicked in, with fiery percussion and tangling pentatonic guitar lines, it was a full-on party, capping a superb festival night that went off without the slightest hitch.

Such a pity so few non-locals were there to enjoy. The forlorn vendors and pirogue tour leaders at the abandoned main site downtown bemoaned their solitude, and voiced a strong sentiment that canceling the big concerts had been excessively cautious. Hard for an outsider to judge. All we can do is hope the full show goes on next year.

A discussion in Segou

The next morning, the Festival hosted a lively discussion at Segou City Hall. The theme was “How to Live Together in a Perspective of Durable Peace in Mali.” This is the key question Malians now face, and while we feared that the morning might unfold as a succession of well-intentioned platitudes, we were pleased instead to hear a passionate airing of diverse views from a room full of engaged participants. The three festival organizers each spoke. Festival in the Desert director Manny Ansar voiced his impatience at having to constantly prove that, as a Tuareg, he was not a rebel or an extremist. The complaint was reminiscent of those heard by Muslim-Americans in present day U.S.—an intriguing parallel. Taragalte festival director Halim Sbai cast Mali’s problems in the larger context of the Sahara Desert, in particular focusing on the lucrative cocaine trafficking trade that has enormously complicated prospects for peace in recent years. And Niger Festival director Mamou Daffe pledged his festival’s determination to sustain the struggle for peace through culture.

Fadimata from Tartit during a discussion in Segou

But just as moving were the voices of citizens and artists, such as Tartit’s Fadimata Wallet Oumar (Disco), who recounted her experience of twice being driven into refugee camps due to conflicts she clearly felt could have been avoided. People told their personal stories, and though all shared a desire to see a united Mali, they were not shy about voicing their complaints. One theme in the discussion—which we will explore in our broadcasts—is the feeling that the north has been systematically neglected throughout Mali’s history, and that it lags behind the rest of the country in terms of development. There is a kind of automatic response to this, heard in this discussion, something like: You’re not alone; there are neglected areas throughout the country. No doubt this is true, but it is a little too easy to dismiss the particular woes of the desert north in this way, and there was firm push back on this notion. What was inspiring here is that, for all the strong emotions aired, the discussion was just that, a respectful back and forth, edged with deep frustrations but never disrespectful or bellicose.

Niger River

The last word went to the head of an association dedicated to the tradition of Sinankuya—in which members of certain families, for historical reasons, enjoy the right to insult each other playfully. This ingenious system of releasing tensions between ethnic groups and clans has helped sustain peace in Mali since the time of Sunjata in the 13th century. Its ongoing relevance was powerfully on display during this remarkable discussion.

Khaira Arby

Back in Bamako, we resumed our quest for music and musicians in this inexhaustible city. Khaira Arby, the “Nightingale of the North,” invited us to attend a wedding where she performed with her group. We recognized Khaira’s searing cry from blocks away. Her prodigy, lead guitarist Abdramane Toure, was in top form as ever, spilling out a flood of ecstatic, psychedelic riffs that both echoed and transformed the blazing fluidity of his hero Jimi Hendrix. We were escorted to the heart of the action, seated with the band, just behind Khaira. Banning was immediately instructed to plug in and play (second) rhythm guitar, barely audible, but present amid the din of electric sound.

Guests dashing Khaira Arby money

This wedding, attended mostly by Songhai, Tuareg and Fulani families—some in exile from the north—had a different energy from the Mande wedding Kasse Made Diabaté had invited us to the week before. At both events, the crowd of mostly women were dressed in dazzling robes, headdresses, makeup and jewelry. And they made their rounds producing cash from colorful purses to press into the hands of the singer—in this case, Khaira. Bless Khaira for instructing the donors to direct a few crisp CFA notes to the visiting toubabs. But here, when the money appeared, bystanders muscled in, aggressively trying to intercept it. Fired by the music and money, the crowd surged towards the action. Khaira’s male attendant, and at one point the singer herself, had to intervene and shove a swath of celebrants 10 feet back. And we mean shove. This was contact sport, start to finish, and the music never stopped. Khaira later explained that those grabbing for money were effectively wedding crashers from the neighborhood. She clearly found them irritating, though at the same time, showed some compassion for their circumstances as exiles in Bamako.

Adama Diarra and his students

Adama Diarra and his students

Students of Adama Diarra

A central focus of our reporting of this trip has to do with the transmission of traditional culture in 21st century Bamako. Our Hip Deep advisor Lucy Durán (see her work on Growing Into Music in Mali and elsewhere) directed us to the home of a remarkable Bobo musician, Adama Diarra. Adama is a djembefola, a master percussionist. But in recent years, he has created an ensemble of talented children, including his 8-year-old son Khalifa, who plays a pretty mean djembe himself. Over the course of a long Sunday visit, we recorded and filmed some astounding performances by these children, and got a sense of how dedicated they remain to traditional music.

Balafon duo of Daniel Dembele and Waly Coulibaly

Particularly impressive were the balafon duo of Daniel Dembele (age 12) and Waly Coulibaly (6). The precision, confidence and intensity of these young musicians’ performances left us quite dazzled. Adama himself was hesitant to take credit, nothing that both boys are the sons of master balafonists. But there was no doubt that the environment of learning and support that Adama has created in his home is playing a significant role in developing the young musicians we met there. Many will tell you that Mali’s traditions are under threat, and that young musicians no longer work hard at their art. There may be some truth to this, but we saw powerful evidence in private homes and at Bamako’s Institute National des Arts (INA), that the transmission of traditional culture to young Malians is absolutely alive and well if you know where to look.

Tiemoko and Ousmane Dagnon

We made late-night forays into neighborhood music venues to see up-and-coming acts. At Habib Koite’s Hotel Maya, we caught a crisp set by Gambari Band, a spinoff from Bassekou’s Ngoni Ba led by Bassekou’s ngoni-playing brother Fousseyni Kouyaté. This is a band to watch, as you can hear from their just released debut CD, Kokuma. A more traditional ngoni player, Ousmane Dagnon (son of the late griot singer Bako Dagnon) encouraged us to come hear his band at a remote nightclub simply called @. Expecting something very traditional, we were pleasantly surprised to find a freewheeling ensemble that also featuring kamele ngoni (from Wassoulou music) electric guitar, bass and drums, and a rotating set of singers. This was more or less a jam session, reminiscent of the variety bands we’ve heard at so many unheralded Bamako night spots over the years. But the level of musicianship was fantastic, and the spirit of the performances clearly electrified the young crowd, as they sipped beer and whiskey and smoked flavored tobacco out of hookahs. Very good to know that this sort of grassroots, neighborhood music remains a vital part of Bamako night life.

Sidiki Diabaté

Toumani Diabaté and his son Sidiki can be tough to schedule interviews with—both are in high demand. But right at the end of our visit, we lucked into individual conversations with each of them at Toumani’s busy compound. Sidiki, speaking generously on his 25th birthday, gave a detailed account of his evolution from apprentice kora player and griot to international pop singer and heartthrob. Stay tuned for his intriguing insights on how these two identities coexist comfortably. And Toumani treated us to a thoughtful discussion of Malian society and music, ranging from the unwelcome influence of fundamentalist (Wahhabi) Islam, to the changing (or not) nature of griot traditions.

Salif Keita practicing with his band in Bamako

En route to the airport, we dropped in on Mali’s greatest superstar, Salif Keita, who has created an impressive complex of radio station, recording studio, nightclub, office and rehearsal hall in the neighborhood of Kaliban Koro, across the Niger River from Bamako’s downtown. We went on air with the director of Radio Nassiraoulé (The Voice of Mande) to discuss our work and impressions of musical life in Mali, post crisis. Then, in the orangey twilight, we took a motorized canoe across a narrow channel to Salif’s island, complete with a set of bungalows for guests, an open-air bar and performance space with room for over a thousand fans. The island project was begun before the crisis, and its eventual fate is unclear, but what a treat it would be to hear Salif’s band here! As it was, our sendoff was watching Salif rehearse the band—including Madou Sidiki Diabaté (Toumani’s “brother”) on kora and the inimitable Harouna Samaké on kamele ngoni—for a major concert scheduled in Bamako for Feb. 13. Salif listened closely to each groove, moving around the circle to tweak a conga part here, a kamele ngoni riff there. When he was happy he sang, sublimely, as only he can.

Ahmed Amanar

This was the sound that carried us to the airport, ending a trip that vividly rekindled our belief in this singularly musical nation. The political, social, religious and economic problems in Mali are real and daunting. But it’s hard to doubt the future of a country with such diverse and vital musical culture, so vigorously supported by citizens, institutions and international fans alike. We left very sure that better days lie ahead for Mali.

Thanks to all our hosts and musical friends in Mali and to our Hip Deep advisors.

Thanks to the National Endowment for the Humanities, our lead funder for Hip Deep on Afropop Worldwide. Thanks also to PRI, our stations across the U.S., and individual donors around the globe for their support of Hip Deep as well.

Stay tuned for Hip Deep programs and podcasts from Mali this spring. In the meantime, check out our fascinating 2008 (pre-crisis) program Mali: A History in Music.

Stay tuned for Hip Deep programs and podcasts from Mali this spring. In the meantime, check out our fascinating 2008 (pre-crisis) program Mali: A History in Music.