Ahmad Sikainga is a Professor of African and African America Studies at Ohio State University, specializing in African economic social history, with a focus on slavery, emancipation, labor, and urban history. He holds an MA from Khartoum University (Sudan) and a Ph.D from University of California, Santa Barbara. Professor Sikainga was a Mellon Fellow at Harvard University and in 1996-97 he was a Fulbright Scholar in Morocco. His current research examines the role of slavery, ethnicity, and identity in the development of popular culture in contemporary Sudan. His publications include: Sudan Defence Force: Origin and Role, 1925-1955 (1983), Western Bahr al-Ghazal Under British Rule, 1898-1956 (1991), Slaves into Workers: Emancipation and Labor in Colonial Sudan (1996), and several articles. He co-edited Civil War in the Sudan, 1983-1989 (1993). His most recent book is City of Steel and Fire: A Social History of Atbara, Sudan's Railway Town, 1906-1984. In 2006 he co-edited Post-Conflict Reconstruction in Africa (Africa World Press). He is currently working on a book project on the development of popular culture in contemporary Sudan.

Professor Sikainga was the principle scholarly source for Afropop Worldwide’s Hip Deep program, Sudan: A Musical History. Below is his complete conversation with Afropop’s Banning Eyre, on April 6. 2008.

Banning Eyre: Let's start with you. Just introduce yourself, and tell us a little bit about yourself and your background.

Ahmad Sikainga: Okay, well I was born and raised in the Sudan in the region of Merawe, in the far north. Merawe, of course, was the center of the ancient kingdom of Nubia. I attended University of Khartoum, and then went to Nigeria where I taught at Bayero University in Kano, and Amadou Bello University in Zaria. From Nigeria, I came to the United States for my graduate studies, and I received a doctorate in African history from the University of California at Santa Barbara. Currently, I teach African history at Ohio State University.

B.E.: Talk a little bit about your studies, your field of research, and particularly what you've come to focus on recently.

A.S.: My area of interest is the social and economic history of the Sudan and the Nile Valley in general, with a focus on slavery, labor, and the urban history. Currently, I'm working on a research project that examines the link between ethnicity, identity, and the development of popular culture in contemporary Sudan. I am particularly interested in the contributions of marginalized groups in the Sudan, such as ex-slaves, their descendents, women, workers, immigrants to the development of distinctive styles of music and dance and fashion that have really become the hallmark of urban popular culture in Sudan today.

B.E.: Great. Let's start with a little on the history of Sudan. What is it that people really need to know about Sudan in order to understand its cultural and political realities today?

A.S.: Well, Sudan, first is the largest country in Africa. It shares borders with its nine neighbors: Egypt in the north, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, the Congo, the Central African Republic in the Southwest, Chad in the West, and Libya in the North West. The major geographical feature is the Nile, which straddles the country from south to north. Sudan is perhaps one of the most diverse countries in Africa. Its population represents, we could say, a multitude of ethnic, linguistic, and religious groups. They include Arabic speakers, as well as Nubians, Beja, Nuba, Dinka, Shuluk Zandi, West African immigrants such as Hausa, Fulani and Burno, Egyptians, Middle Easterners, Coptic Christians, and so forth, just to name a few. So it's a remarkably diverse country.

The majority of the population is Muslim, representing about 72 to 75%. The rest are following either traditional African religions, or Christianity. Now in ancient times, the northern part of Sudan was dominated by the Kingdom of Nubia, or Kush. This kingdom dominated the northern parts of the Sudan from the 8th century BC to 4th century AD. At some point, Nubia actually ruled Egypt. In fact, the 25th dynasty that ruled Egypt was Nubians, and the most famous famous Nubian rulers were Piankhe and Taharqa whose names were mentioned in the Book of Kings, in the Bible.

The Kingdom of Nubia was destroyed about 350 A.D. by the armies of Axum. Then, from the 6th century A.D., Coptic Christianity spread in Nubia, and three Christian kingdoms emerged. But following the Arab-Muslim conquest of Egypt in the 7th century, Christians Nubia came under growing pressure, but they were able to resist Muslim Egypt for several centuries. However, the gradual infiltration of Arab Muslims from Egypt, as well as from Arabia across the Red Sea, led to the decline of Christianity in Nubia and the gradual spread of Islam. So, by the beginning of the 16th century, the first Muslim state emerged in what is today northern Sudan, and it was called the Fung Kingdom, with its capital in Sennar. Another Muslim kingdom emerged further west, and that is the Kingdom of Darfur. These two kingdoms played a very important role in the spread of Islam in Sudan by encouraging the migration and settlement of many Muslim teachers and leaders from Arabia, Egypt, and from other parts of Africa.

So you could say that in this regard, Sudan is no different from West Africa in the sense that Islam was associated with Sufism, or Muslim mysticism, and it was kind of egalitarian Islam. It incorporated many of the traditional, existing belief systems, and it was much more tolerant.

The Fung Kingdom dominated most of what is northern Sudan today until about 1821 when it was conquered by the invading armies of Mohammed Ali, the Ottoman ruler of Egypt. This period is known in Sudanese history as the Turkiyya, the Turco-Egyptian period. It was perhaps one of the most critical periods of Sudanese history, because it brought about numerous changes. First, Mohammad Ali's main goal was to create a slave army by recruiting Sudanese from different parts of Sudan, and to exploit the natural resources of the country. In this regard, the Turco-Egyptian government sent armed expeditions to raid the non-Muslim, African regions of southern Sudan, the Sudan Ethiopian border, the Central African Republic, and Chad.

Most of the captives were drafted into Muhamad Ali's army. But many were sold in the markets either in the Middle East or in northern Sudan. So slavery and the slave trade became widespread in the Sudan in the 19th century. Many traders and adventurers from the Middle East, and northern Sudan, as well as a few Europeans, established their headquarters in Khartoum, the capital, and engaged in the business of ivory, and the slave trade. But under growing pressure from European governments, the Turco Egyptian government tried to end the slave trade in the 1870s by extending its control over the equatorial provinces. That's actually how the regions of southern Sudan were incorporated into the present day modern Sudan. That was in the late 1870s. They did it basically through the employment of European officers such as Samuel Baker, and later General Gordon.

I should say, as a sort of footnote, we talked earlier about a slave-based army. In fact, in the 1860s a Sudanese battalion was sent to Mexico to help the French to quell a rebellion there at that time, and they spent about four years there.

Now, the Turkish period was perhaps one of the most oppressive periods of Sudanese history—the taxation, the slave trade, and so on. And all of this provoked rebellion in 1881, led by a man called Muhammadd Ahmad, the Mahdi, or the "guided one." This was a religiously inspired movement, and it sought to overthrow the Turkish regime and establish an "authentic" Islamic state in Sudan. So using guerrilla warfare, the Mahdi did succeed in overthrowing the Turkish government in 1884, and he established the Mahdi state, which ruled the Sudan until 1898, when the British and the Egyptians reconquered the Sudan and established what is called the Anglo Egyptian regime, or sometimes the Condominium.

B.E.: Condominium. Such an odd phrase.

A.S.: This is a unique arrangement, whereby it's supposed to be a joint administration, but in reality, the British had the upper hand. This period is basically a continuation of the earlier Turco Egyptian policies. But the main thing is that it administered southern Sudan and northern Sudan as separate entities. The British felt the South was culturally different from the north, and so it was administered separately. However, in the 1940s, this policy was abolished, and the British decided that the future of the South would be part of a unified Sudan.

B.E.: Of course, by that time, a dangerous dynamic had been set up, right? Because the South had never really been brought into the fold as it were.

A.S.: Exactly.

B.E.: That seems like a pretty fateful decision to keep the two regions separate. I understand there were geographical reasons for it. Blockages in the Nile River making it difficult to pass between the two. But also, wasn't there some sort of rebellion afoot in the South that the British also want to keep control of? Was that also part of their reason for wanting to keep the two regions separate?

A.S.: Well, there are several considerations. Definitely, there was resistance in the south against British rule for many years, just like in the north. There were several uprisings. But the policy was initiated in 1929, which came to be known as Southern Policy. Basically, the British tried to discourage the spread of Arabic language and Islam in the south. Some British officials argued that the South was different and it was important to preserve the "traditional" culture. And of course, a number of regulations were instituted, for instance banning northern Sudanese traders from going to the south, also granting permissions. People had to obtain permissions to go to the South. This was part of what was called Closed Districts law, and they included other parts of Sudan such as the Nuba Mountains. So that was the stated rationale, and of course, many Sudanese nationalists considered it as a principal factor behind the north-south conflict. However, that cannot explain what is happening in Sudan since independence. So the Southern policy probably did contribute, but it's not the main reason.

B.E.: I understand. It's complicated. But there was a way in which this kind of policy made it very difficult for the country to come together as a country.

A.S.: Certainly. But also you have other legacies. One of the most important features of colonial policy was uneven development in the sense that it concentrated economic development in the central part of the Sudan—social services, education and so on—and neglected different regions such as the South, Darfur, the East, and even the far north. So this pattern of unequal development is really the main factor behind the continuing uprisings and conflicts in different parts of the Sudan, including the Darfur conflict. And unfortunately, this pattern continued even under the postcolonial Sudanese governments. That is probably one of the main reasons behind the continuing conflict and the threat that the country is going to fall apart. So it's the Southern Policy, coupled with uneven development.

Now with regard to anticolonial resistance and nationalism, two things: Just like many other parts of Africa, there was continuous resistance against colonial rule. It was led there by different social groups. Initially, it was led by religious leaders, and then later on, you have peasant resistance. You have workers’ resistance. In fact, by the 1940s, Sudan had one of the most militant labor movements, associated mainly with the railway workers. It was probably one of the most radical labor movements in Africa and the Middle East. It was also a movement that was closely associated with the Sudanese Communist Party, which was the second largest Communist Party in Africa, perhaps after the South African Communist Party. That is until 1971, when it was finally destroyed.

B.E.: So this powerful Sudanese labor union movement comes in the late 40s.

A.S.: In the late 40s. Yes. That's the basis of the labor movement. And again, it followed the general pattern in other parts of Africa. With the nationalist movement itself, it started amongst a small, educated class, mainly the graduates of Gordon Memorial College, which was established by the British in 1905. The leaders of the nationalist movement are secular in their orientation. But the two main political parties that led nationalism and came to power after independence are closely associated with the the two religious sects, namely the Khatimiyya and Mahdiyya. So this has become one of the main characteristics of the two main political parties in Sudan, the National Unionist Party and the Umma Party. They held power whenever you had democratic rule from independence until they were finally overthrown in 1989. Of course, the postcolonial period of Sudanese history was punctuated by military coups and so on, and so on, so you have this vacillation between civilian rule and military rule.

B.E.: And it would seem that no very strong leaders until 1989, with the exception of Nimeiri.

A.S.: Well, Nimeiri took over in 1969. Actually, he ruled from 1969 until 1985. And of course, it was also a very significant period, because initially, Nimeiri was backed by the Communist Party, and the first couple of years he had a socialist orientation, and then he turned against the Communist Party. Of course, before that, during his socialist phase, he dealt a serious blow to the sectarian parties, basically the Mahdists. And then of course, afterwards, he turned against the Communist Party.

Nimeiri

But one of the most important developments during Nimeiri's time was the signing of the Addis Ababa agreement in 1972, which ended the first civil war between the north and the south. And there was relative peace in the South until 1983, and he himself actually destroyed the agreement as a result of his own politics. He tried to redivide the South into several regions, and also he introduced Sharia law (Islamic law, or September Laws as they were known in Sudan). And that's a major change in modern Sudanese history. because for the first time in the 20th century, you have an attempt to actually apply Islamic law in the Sudan. So it's important to remember that although there are several constituencies that demand or embrace this idea of an Islamic state, it has never been actually implemented except under military regimes, Nimeiri and the more recent one.

B.E.: Interesting. But if Nimeiri started out as a communist or a socialist, how did he end up being the one who introduced Sharia law? Was that just an attempt to appease religious factions, or did he really believe in that?

A.S.: Well, a couple of things. First, when he was supported by the Communists, basically he needed a base of support. Nimeiri was a survivor. He was supported by the Communists and he used them. Actually he used them to deal with the sectarian parties. And then after he dealt with the Communists, he signed a peace agreement with the South, and the South for quite some time, became the main base of his support. Then, in the late 1970s, there was a continuous opposition by the religious parties as well as the Muslim Brothers. And they made several coup attempts against him. So he felt that he could not just rely on the support of the South, and at that point, he engaged in what was called “national reconciliation.” And that is when he brought the sectarian parties, the Umma and National Unionists, but most importantly, the Muslim Brothers led by Hasan Turabi, and that's what really helped the Islamist movement to take advantage of the situation and established a very strong economic base as well as political support. It was during this period that the Islamicists began to plan for the future takeover of power. So that was quite important. The introduction of Islamic law also happened under the influence of the Islamicists who became part of his regime.

B.E.: So this was his attempt to appease them and hopefully stay in power, but in the end it wasn't enough.

A.S.: Of course, it's one of the factors that ignited the second Civil War in the South.

B.E.: So he introduced Sharia law and what year?

A.S.: That was September 1983.

B.E.: Right at the moment when the war starts again.

A.S.: But also, for the purpose of our discussion, this was the period when Nimeiri launched a massive campaign against that involved closing bars, banning alcoholic drinks, and generally harassing people. It was a period of severe repression on all levels - social and cultural. That was the beginning of a very ugly chapter in modern Sudanese history and social life. But of course, even after Nimeiri was overthrown by a popular uprising in 1985, the subsequent rulers really didn't try to repeal the September laws. They actually kept them in tact.

B.E.: What was the basis of the opposition that ultimately threw Nimeiri out?

A.S.: Basically, the political repression that prevailed throughout his years. It was basically a police state.

B.E.: Especially after 1983.

A.S.: But even before that; the national reconciliation did not bring any democratic change. They were all incorporated into his single party, the Sudan Socialist Union. So you had political repression at the same time there were severe economic problems. Inflation was very high as well as unemployment. People were really experiencing serious hardship. So it started as a spontaneous uprising by people in the streets, and then it spread to involve professional associations, trade unions, and so forth. So that was the basis for the uprising in 1985. April. This day actually marks it, April 6.

B.E.: Between 1985 and the rise of the current government in 1989 must have been a pretty turbulent time. What were those years like?

Nimeiri

A.S.: First of all, after the uprising, Nimeiri was overthrown by some of his generals. They established a transitional military government from 1985 to 86, and in 1986, general elections were held, and the main party that dominated the government at the time were the Umma party and the National Unionists. Both of them are sectarian. And the Muslim Brothers or the National Islamic Front, came third. So this was a period when the war in the south was still going on. There were several attempts to reach a peace settlement, but in fact, on the eve of the coup of 1989, one of the parties - the National Unionist Party, signed a protocol with the SPLA (with John Garang), and it was suppose to make substantial progress toward peace, but Sadiq al-Mahdi, the prime minister at the time, refused to ratify it, and in fact, this was considered perhaps one of the main reasons behind the coup. The national Islamic Front felt that this was going to be a major concession to the south, and a major compromise, and they were not willing to do that. So the possibility of a deal, a peace deal, was one of the main factors behind the June 30th, 1989 coup.

B.E.: To prevent that from happening.

A.S.: To prevent that from happening. They felt that it was going to mean compromise on Sharia, and that it was going to give too much concession to the SPLA.

B.E.: So that shows that from the beginning, this government was committed to fighting and winning that war in the south, rather than conceding anything.

A.S.: Yes, in fact, one would argue that of all the political parties in northern Sudan, many of them probably shared similar views when it came to the south, but I think this is probably one of the most uncompromising groups, vis-à-vis the South.

B.E.: Fascinating. So we are up to 1989. It's interesting, because a lot of the musicians that I have interviewed cite 1989 as a moment that really changed their lives. But it sounds to me like things like the closing down of bars, creating difficulties for recording, the sort of things that would affect the lives of musicians, really has started back in 1983 and had been holding up. So how big a change was it in 1989 when that coup happened?

A.S.: Well, to begin with, the regime actually overthrew a democratically elected government and established perhaps one of the most oppressive and dictatorial regimes in modern Sudanese history. It actually inaugurated a regime of terror, in which political activity was banned and freedom of expression was completely abolished. Then thousands of people were detained, tortured, or sometimes killed. It also pursued the war in the south with great vigor, actually executing the war and framing it in the form of jihad. And that is definitely an element in the conflict. At the same time, the regime actually came with a very ambitious project, the so-called the "civiliztion project." This involved the complete transformation of Sudanese society, thorough Arabization and Islamization. They also embraced a supremacist ideology, and we can see that in the conflict in Darfur today, and in other marginalized regions.

At the same time, the regime saw itself as the center of this Islamic revolution that was going to spread to other parts of Africa, and the Middle East. So it was a monumental change. With regard to the area of culture, the regime was equipped with this ideology of, as I said, the "civilization project," which involved Arabization and Islamization. So they viewed all “liberal and secular” practices in Sudanese society as a form of heresy. There were numerous public orders and laws and curfews, banning parties, even private parties such as wedding parties were banned or people had to get permission to hold these parties. Sometimes the security forces broke into people's homes, and if the parties went after 11 o'clock, quite often the performers were beaten or imprisoned. At the same time, they introduced new laws governing dress and fashion and so forth. They imposed what is called the “Islamic dress”, although it is unclear really what that means. They enforced a very strict code and violators, particularly women, were either beaten on the street or imprisoned.

B.E.: So this was a big change.

A.S.: It was a huge change.

B.E.: Let's talk specifically about how all this affected musicians, particularly in contrast to what it was like before.

A.S.: The whole cultural environment that was created was new. First of all, the repressive policies, the purging of the civil service, the army, and the police forced many people to leave the country. It basically decimated the middle class. So you had many people, including performers, leaving the country. And the general environment was just not conducive for any kind of artistic or creative activity. It was a reign of terror. I think that for art to flourish, it requires a certain environment. Even the public spaces that were open to people for these kinds of activities, were suddenly unavailable.

B.E.: Give me a sense of what it was like before that, before 1983. I know there was a state orchestra. Do you hear a lot of music on radio? Television? What was the live scene like?

A.S.: Colonial rule brought rapid social and economic change, growth of urban centers, and rural-to-urban migration. You also had the abolition of slavery. So many marginal groups moved into the cities from other parts of Sudan and established neighborhoods, and in these neighborhoods they developed very vibrant popular culture involving music, public festivals, and so on. One of the most important influences was that of Sudanese soldiers who served in the Egyptian army, the modern Egyptian army in the 20th century. Many of these soldiers were trained in Western musical instruments such as brass instruments and so on. They played a major role in the introduction of new styles of music -modern music, particularly after they were discharged from the army. In the 1920s, you have a number of recording companies. There was a well-known Sudanese of Greek descent, Dmitri Albazar, who played a major role in recording Sudanese singers, and in the 1930s, including many Sudanese women singers. At that time, there were two dominant forms of music: you have the haqiba, which is mainly vocal, and also a new form called tum tum, which was introduced by these groups. It emerged in the 1920s and 1930s, and rapidly became popular.

The most critical development was the establishment of Radio Omdurman during World War II. The establishment of the radio really played a major role in the dissemination of this new urban music throughout the country. It is important to point out that the radio was established by the British mainly as war propaganda machine. But in fact, it evolved to become the main radio station in the country. So you can really say that the period of the 1940s, the 1950s, and throughout the 1960s, was the peak. It was a fairly liberal environment, and it was really the golden age of Sudanese music. You had a variety of styles, from traditional Sudanese music to jazz bands, exhibiting the influence of North American, Latin American, even Congolese and so forth. So it was this liberal social and cultural environment that really led to this. You had musical performances in wedding parties, and all sorts of social occasions, festivals and so on. But also, Khartoum was a highly cosmopolitan town with clubs, dance halls, cafés, movie theaters, and even bars. All of that came to an end in the early 80s, with the introduction of Nimeiri’s policies, which intended to eradicate all of these practices that were really the hallmark of Sudanese urban popular culture.

B.E.: So even in the early 80s, things are really already very much clamped down on, and then in 1989, it's even worse.

A.S.: Yes, you could say that was really the straw that broke the camel's back.

B.E.: So what happened after 1989, for the musicians, for the radio station, for all those recordings from the golden era?

A.S.: Well, first of all, the most dominant force was religion. There was religious music and all the programs were oriented towards religion, both on TV and on the radio. At some point, there was hardly any other kind of music played. A lot of songs that were popularized were mainly geared towards executing the civil war in the south, what came to be known as called "jihad songs." This became the most dominant form of music and entertaining during this period, especially during the 90s.

B.E.: When you say "jihad songs" these are literally songs that are encouraging people from the north to fight against people from the South. Is that right?

A.S.: Well, they're basically glorifying the army. It was framed under the rubric that the Sudan was under threat, and this is almost a kind of nationalism, so it was basically praise songs for the army and the militias.

B.E.: I have heard anecdotally that many of those historic radio recordings from the earlier period were destroyed by the regime. What do you know about that?

A.S.: Well, there were rumors that some of the recordings were destroyed, but it is very difficult to verify that. According to some people, that has not happened. Maybe one could assume that some material was lost, but at any rate, most of the archives at the radio and as well as Sudan television are hardly accessible; there are a lot of restrictions. So people really don't know what is exactly there. That's why it is very difficult to verify whether some destruction happened. But definitely, for quite some time, you could hardly hear these songs on radio. I think this has changed now.

B.E.: Yousif El Mosely, the Sudanese composer and orchestra director who now lives in Monterey, California, tells a very interesting story about being in Egypt at the time of the assassination attempt of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak. This is in 1996. Apparently it was determined that the Sudanese government was involved. This is an important occurrence for Yousif, because the Sudanese community he was living among Egypt faced reprisals. He responded by writing a song that was in some ways an apology to Egypt, and of course he was very much denounced for that by officials back in Sudan. What you know about that incident?

A.S.: This was part of the regime's grand scheme. Hassan Turabi , the power behind the scene, dreamed about creating a chain of Muslim states across Africa and into the Middle East, and of course Egypt figured prominently in that scheme. Because of its strategic importance, its position in the Arab world and so on, they assumed that if Egypt fell into the hands of the Islamists, there would be serious ripple effects, and of course they also assumed that to achieve that, you needed to eliminate the head of the state. By doing that the government would collapse, and this would pave the way for the Islamicist takeover. Also, you know, having an Islamcist state next door would have given them tremendous support and power, so it was part of this larger scheme and in that context. They also felt that Egypt at that time was hosting the Sudanese opposition groups, individuals and so forth. So this is the context for the assassination attempt.

B.E.: Okay, so it's pretty much undisputed fact that Sudan was behind this assassination attempt.

A.S.: Mm hmm.

B.E.: And what about Yousif’s story and song, “Salimta”? What you remember about that?

A.S.: I don't know about the song itself, but El Mosely is definitely a well-known musician in Sudan, and he's an accomplished artist and a very hard worker. But the general context is that in the early 1990s, a large number, maybe thousands or even millions of Sudanese flocked to Egypt. Most of those were either refugees or people who were seeking political asylum. So Egypt offered asylum during that period, including for the opposition. But unfortunately, as always, whenever the relationship between the Sudanese government and the Egyptian government deteriorates, it immediately reflects upon Egyptian attitudes towards the Sudanese community, or the Sudanese visitors to Egypt at the time. So what happens at the official level is immediately reflected on the ground. You have probably heard more recently of the situation with southern Sudanese refugees in Egypt, where the police dealt with them in a very harsh way. Many Sudanese took advantage of asylum but it was a very difficult experience for many. In fact, they tried to use it as a stage from which to go somewhere else, either to Europe or the United States. So that's the general context. But at the same time, you could say that historically, in terms of Sudanese singers and performers, there has been this interchange, exchange, and movement of people between Egypt and Sudan. In fact, at some point, there was a radio station in Egypt called Voice of Sudan Radio based in Cairo, which broadcast Sudanese music.

B.E.: When would that have been?

A.S.: I can't remember the exact date, but probably the 1950s, but it was a very important station.

B.E.: I would like to get your impression of a few of the artists that I've been able to interview for this program. Let's start with the female vocal group, Al Balabil. What you remember about them?

Al Balabil

A.S.: Balabil actually came up in the 70s. That's when they were really popular. These three sisters, who formed this group, were probably the most dynamic female singers in Sudan. They continued the tradition, a long tradition, of women singers in Sudan. The first and most famous was one by the name of Aisha el Fellatiya, who is a Sudanese of West African origin (Hausa-Fulani) and she made it in the late 1930s and 1940s. So they continue that tradition. I think their experience was quite significant in the sense that they were quite daring in a society that was not open to women singers. And they were great performers, so they really introduced what you might call a new style that really had a lasting impact. Balabil are still remembered and cherished by many people in the Sudan.

B.E.: When I spoke with them, they told me two things. First they really opened things up in modern times for women singers, because there were not very many women singers who were performing the way they did at that time. The other was that they were proud of was the way they introduced Nubian rhythms, melodies, and language into their performances, and into the popular mainstream. They make a connection between the two, because they say that in Nubian culture, men and women are much more equal, and for them it was very natural to be in the public eye, assertive, open. In other words, they came with a different attitude towards what women could and should do, and they link this to their Nubian background. I'd be interested to hear your comments on that.

A.S.: Well, first of all, let me distinguish between Nubian and Nuba. The term Nuba refers to the inhabitants of the Nuba Mountains in the West. Nubians refers to people who speak a variety of Nubian dialects in the far north (northern Sudan) as well as southern Egypt. Balabil came from the Nubians in the far north, but I believe that they grew up in the town of Kassala in Eastern Sudan and then moved to Khartoum. So the Nubians have always perceived themselves as being very distinct from the rest of Sudan in that they are the inheritors of this very rich cultural tradition, and they're very proud of their identity as Nubians. It is commonplace that the Nubian attitude towards religion tends to be much more liberal, and they are generally known to be much more socially liberal than others. And so in this regard, this feeling of distinctiveness and pride in their cultural identity is really one of the hallmarks of the Nubian personality.

B.E.: Okay. And were there other popular singers on Sudan radio or singing in the Nubian language?

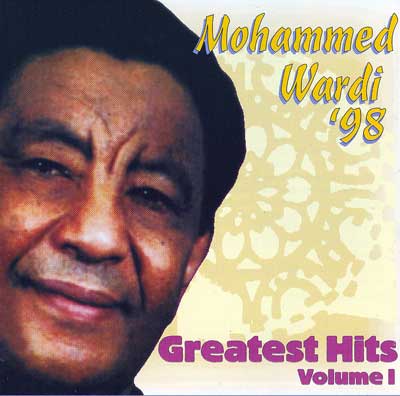

A.S.: Oh, definitely. You had many. Of course the famous Sudanese singer, Mohammed Wardi, is Nubian. He started singing Nubian songs even before Al Balabil for he started singing in the 1950s. And then you have Zaki Abdel Karim, and many others. So it's quite common. In fact there was a a radio program called Rubu` al Sudan, which was geared to broadcasting music from east, west, south and from different ethnic groups in Sudan, and that really introduced Sudanese from different parts of the country to each other's music and songs.

Mohammed Wardi

B.E.: Now, I have the sense that there were some areas of Sudan that were pretty much left out of that mix. I guess I am mostly referring to the south. But let's take them one at a time. Let's start by talking about Darfur. I did a wonderful interview with Omer Ihsas in which he describes coming to Khartoum as a talented singer, but feeling that the music of Darfur, the music he grew up with, was not really represented in the music on national radio, and on the national stage. So he goes home to dedicate himself to researching and transforming the folklore of his home region, Darfur. He explained that when he first began presenting this music in the capital, people suspected him of being political, just standing up for his region essentially. But eventually he earned trust for a repertoire that he now calls "Sudanese songs from Darfur." In other words a national, as opposed to a regional music, but one that really reflects the folklore and culture of the place he came from, which he had felt was missing up to that point. Does that story sound about right to you? And talk about Darfur as a cultural expression on the national stage.

Omer Ihsas

A.S.: Well, I think I would put it in a larger context in the sense that I think one can argue that music and popular culture in Sudan is a real site of struggle between the competing paradigms of Sudanese identity: Arabism and Africanism. So I think one can talk about cultural marginality just like we talk about marginalization in terms of economic underdevelopment, and so forth. You could say that Omdurman radio station, the official radio station, is dominated, and has always been dominated by the government, and the government has always been dominated by a small elite from the northern, or the central part of the country. And in that regard performers, not just from Darfur, but from different parts of the country felt that Radio Omdurman basically promoted and disseminated a particular kind of music, mainly the urban music of the center. So performers from places like Darfur, the East, the South, the Nuba Mountains, the far north, have not really been represented. There were a few attempts, in fact, in the 1970s, there were several singers from Kordofan, such as Abdel Gadir Salim, and others, who came to Khartoum and they were given a lot of attention.

Abdel Gadir Salim

But that is definitely not the case with Darfur. Darfur is a huge region. It is inhabited by a large number of ethnic and linguistic groups, including Arabic speaking as well as other groups such as the Fur, the Masalit, the Zaghawa, and so forth, and each of these groups has a very rich cultural tradition in music, dance, performance, and so on. But all of that, like I said, did not get a chance to be represented in the center. So I would put in this larger context.

B.E.: What is your impression of Omer Ihsas?

A.S.: I think one of his main contributions is that he introduced the music of Darfur, but he's also an innovator. So you could say his role is somewhat like Abdel Gadir Salim, who used traditional instruments and rhythms from Darfur, and really made it appeal to different constituencies and different audiences from the center of Sudan. I think that was a major change and a major contribution.

B.E.: Okay, so he's something of a modernizer of tradition. That's pretty much the way he presented himself in our interview. What about Abdel Gadir Salim?

A.S.: Abdel Gadir played a huge role in popularizing the musical tradition of Kordofan. I think he believes in the model of Youssou N’Dour, that the best hope for Sudanese music it is to really be based on traditional music, as well as traditional styles. So he made a huge contribution. Today, I would say that he's one of the most significant and influential performers in Sudanese music. He's really one of the few who has been able to make Sudanese music heard across different parts of Africa and outside Africa. He really exposed it in a major way. So he figures prominently.

B.E.: What about Mohammed Wardi?

A.S.: Well, I think he is really the largest giant of Sudanese music. I mean, his music, his life, and his history are quite remarkable. Beside his talent and gift, he was a political activist. He's also known for his nationalistic songs, especially during the time of major political change. His songs inspired many uprisings throughout the modern history of the Sudan, especially after the October 1964 revolution, the popular uprising that overthrew the military regime of General Abboud.

B.E.: Fascinating. I have not had the opportunity to interview him, so I don't really know his story in detail. Perhaps you could tell me a bit more about these political contributions.

A.S.: He was a teacher and he came to Khartoum and started singing in 1957. At that time, there were very few Sudanese singers. He is Nubian, but he has his own distinctive style of singing. He was also associated with the Sudanese left, and he wrote several songs criticizing the military regime at that time. He was imprisoned several times, but most notably during Nimeiri’s regime. There was an attempted communist coup in 1971, and after the failure of that coup, he was detained for more than a year. And after the present regime came to power in 1989, he had to leave the country and lived in exile for several years. He went back to Sudan recently, and he still lives in Khartoum.

B.E.: He's now back there. Does he ever perform?

A.S.: Well, rarely. Mainly because of his health.

B.E.: What about a more recent group, Igd el Jalad?

A.S.: Well, this is one of the new groups. I think they were formed sometime in the 1980s and they really continued the tradition of the old Sudanese singers. Most of them studied at the Institute of Music and Drama. One of their most important features is that the group has always included a woman vocalist, and they the main signature is the choral form of singing. They're highly revered in Sudan today. I think they're one of the few groups who really produced, and have continued to produce new songs, and write new music, unlike many of the new singers, who keep rehashing old songs.

B.E.: The singer I spoke with, Omar Benaga Amir, said that what really made them popular is that they were brave, and willing to talk about the problems of the oppressed and the poor, and that this got them into a lot of trouble. They were harassed, arrested, and eventually, at the time Omar left, the group kind of broke up, but then in more recent times, some of the original members reformed with younger musicians and have continued their group. Do you also see them as a group who have had this tradition of being committed to social activism?

Omar Banaga Amir

A.S.: The problem is that the group has changed quite frequently. I saw a concert of them recently when I was in Khartoum. They are certainly as dynamic as they used to be. I don't know about their politics now, but it is true that in the earlier phase they were quite committed, and most of their music did talk about issues of freedoms, and other issues that were of great concern to the common people. But they are definitely still a wonderful group, who continue to make excellent music.

B.E.: Has there ever been an artist from the South or the Eastern region who has become a huge star, made a big impact in Khartoum?

A.S.: Well, there were several southern Sudanese singers like Yousif Fataki. There was also a famous southern Sudanese saxophone player Abdalla Deng. There were many of them of course, but they were never given an opportunity to perform, or to have that kind of attention, just like some of these other regions. Despite that fact, there was a huge influence from the South on northern Sudanese music in terms of musical instrument and styles. Many of Sudanese jazz singers, actually learned the guitar from southern Sudanese guitar players. And of course, because of southern Sudan’s proximity to Congo, Congolese music is probably the most common and the most popular music in the South.

Yousif Fataki

B.E.: That's very interesting. You're saying that southern Sudanese musicians were more familiar with guitar because of their proximity to Congolese music, and that ended up having an influence on jazz musicians in the capital. Have I got that right?

A.S.: Yeah. A couple of Sudanese jazz players that I interviewed said that many of their earlier generation of jazz singers learned the guitar from some southern Sudanese guitar players. It's only among the jazz bands that began to emerge among the late 1950s and 60s.

B.E.: Tell me about this incident that happened much more recently where a singer was actually stabbed and killed.

A.S.: I believe this was in 1994. I don't know the exact details of the incident. Of course, he was killed when he was in the singer's club in Omdurman. But it is unclear whether the attacker was targeting him specifically or he was just trying to kill any singer he would come across. I think, to put it in a larger context, one would say this is a product of the general environment that prevailed, the whole hostility towards music and singers and the kind of xenophobic and fanatic environment that existed at that time.

B.E.: So in other words, whether he was just a crazy man, or a political fanatic, or whether somebody put them up to it, doesn't really matter. It's still an expression of the general mood and cultural atmosphere at that time.

A.S.: Exactly.

B.E.: And what was the name of that singer?

A.S.: Khogali Osman was very popular. He had his own distinctive style. The thing about Sudanese singers during that time was that each has its own unique style. He was one of those and was very popular especially in weddings and other ceremonies in Khartoum and elsewhere.

B.E.: Okay, we have talked about Salim, Wardi, Al Balbil, Omer Ihsas and a number of others. Who have we left out? Especially in terms of major singers and major musicians of the modern era.

A.S.: Well, there are dozens and dozens. From that generation of Wardi and before him, you have Usman Hussain, you have Abdel Karim el Kabli. And of course, there is the generation before them, although many of those have passed away. In the area of jazz, you have Sherhabeel Ahmed. I think he is a huge figure who probably has to be included in the story. And then, of course you have Mohammed Al Amin, Zaydan Ibrahim, Abu Araki al-Bakheit, and many others.

B.E.: Tell me about Abu Araki. He is one of the singers expected to perform at the 2008 Sudan Festival of Music and Dance.

A.S.: He came along and was popular in the 1970s. He also made a number of contributions, particularly in the area of national songs, just like Wardi. Zaydan Ibrahim is also important. He also started very early, but he has a very distinctive style, and this is someone who was really quite creative. There was no one like him. He's still producing.

B.E.: There is one track I really like from a CD called Treasures of the Golden Era, on the Blue Nile label. It’s by Khdier Bashire.

A.S.: Khidir Bashir, yes. He passed away. He was an excellent performer. You have a long list. If you are talking about the deceased, the list can go on forever.

B.E.: It's interesting. Because the music has so little exposure on the outside, particularly in the West. Maybe I'll ask you this philosophical question that came up quite a bit in the conversations I had with musicians last summer. Why is it that the music of Sudan has not gone out to the outside world as much as music from say other parts of Africa?

A.S.: Well, I think that part of it might be the language barrier, but Sudanese musicians didn't really get into the business of recording CDs. Still, the music was popular. It's very popular in Ethiopia.

B.E.: Yes, Yousif el Mosley told me about Sudanese songs that had been translated into Amharic and performed so much that local people mistook them for Ethiopian songs. So it certainly has had an audience in the region.

A.S.: In the region, but also across the Sudanic belt (the Sahelian belt). For instance, Sudanese music is very popular in Chad, in Niger, in Mali, and in northern Nigeria. But I think because of what happened since the 90s, this has slowed down. I think before that, it was popular. You could buy Sudanese cassettes definitely in places like Chad, northern Nigeria, and so forth. Wardi was very popular in northern Nigeria, even in Cameroon. So I think that's one way to look at it is to look at the similarities of music across that belt from Ethiopia going west.

B.E.: Now, speaking of that, there's an interesting point that Mohamed Ali Mergani, director of the Nile Strings in Virginia made when we spoke. It has to do with the scales used in Sudanese music. In Arabic music you have microtonality and the whole system of maqam, which of course exists very strongly in the Middle East, and somewhat in Egypt. But Mergani says that these Arabic scales exist rarely, or not at all, in Sudanese music. Why is that?

A.S.: I think it's mainly because Sudanese music is a product of local traditions. I'm not an expert in music, but I think it has something to do with the fact that the basis for Sudanese music is actually African—the beat, the basic rhythm. And that's why you find great similarities with Ethiopian music. I think Middle Eastern music and North African music came sort of as an external influence. Even these instruments like oud and violin and so on, these instruments were introduced in the early 20th century or so. There are some Sudanese musicians who try to emulate those styles, but essentially, it followed the same pattern like Ethiopian or Somali music and this Sudanic belt music, and its roots are really in an African beat.

B.E.: That's interesting. When you talk about Ethiopia, you're talking about a country that is largely Christian, with little connection to Middle Eastern and Arabic music, and yet there's a real connection with the music of Sudan, and that goes to the African root. That's a very interesting observation.

Tell me a little bit about what Khartoum is like now. You have been traveling there quite a bit recently. If I go there now, what will I hear on the radio? What will I hear if I go out on the town? Are there nightclubs? Are people performing music? Tell me about musical life in Khartoum now as you know it.

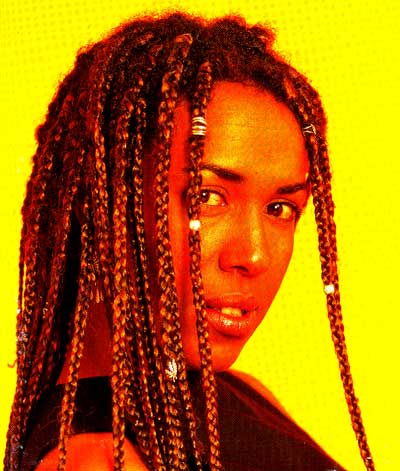

A.S.: Several things. One, I think after the signing of the peace agreement [2005], things have really opened up. It is definitely a much more relaxed atmosphere in terms of social activities and so on. So you find a lot of music, a lot of parties, and so on. But unfortunately, what happened is that during this period, from the 90s on, basically you have very little activity in terms of music production and new performers. What's happening now is that people are just rehashing the old music. There are very few groups, with the exception of Igd Al-Jalad and a few others, and Rasha of course, who are having their own music. At the same time, there is a major change in that the use of the whole orchestra—violin, loud, guitar, and so on— is disappearing, I think mainly because of economics. So they're basically replaced with keyboards and organ. People are complaining about that; this is really distorting the music. So you have a large number of young, male and female singers, but they are just repeating and singing old songs from that golden era. There are lots of them.

Rasha

The radio stations: there are a few radio stations now beside Omdurman, and some of them really do play some of these old songs and they are quite popular. So that's a place where you can find some of the old music. Generally, I think the environment is much, much better than in the 1990s.

B.E.: But now the artists need to respond with some creativity and innovation. Is that which are saying?

A.S.: Exactly.

B.E.: Let me ask you about a popular singe from the south, Emmanuel Kembe. He performed last summer at the Sudan Festival of Music and Dance in New York. What do you know about him?

Emmanuel Kembe

A.S.: Emmanuel Kembe comes from a small ethnic group in southwestern Sudan, near Central Africa Republic. His music is influenced by Congolese music, particularly Franco. His songs talk about peace and unity. He was in Sudan recently and he did an interview with a local newspaper in which he spoke about his intention of returning to Sudan to contribute in the reconstruction of southern Sudan. I believe he now lives in North Carolina.

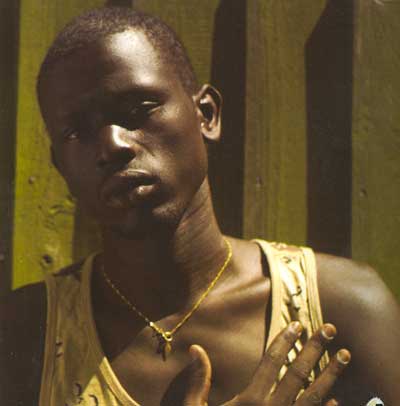

B.E.: That’s right. And that’s very interesting that he wants to go back, because I too interviewed him, and he went through quite an ordeal to get himself to the U.S.. What about rap and hip-hop music, youth music? We've been hearing a lot about another southern Sudanese musician, this young rapper Emmanuel Jal. Are you familiar with his work?

Emmanuel Jal

A.S.: He is probably one more well-known outside Sudan than inside Sudan, mainly because of the way the radio stations are controlled and run. But I think rap and hip-hop, are becoming very popular among the youth. One of the most important developments in Sudan music recently is the huge advance in terms of technology, communication technology, satellite TV, and so on. The youth are really exposed to rap and hip hop, but also, you can see a growing influence of music from the Middle East, especially from the Gulf. That's also taking hold. So you see two strands of influence: on the one hand you have hip-hop and rap, on the other hand, you have this influence from the Middle East.

B.E.: And particularly the Gulf, you say. You are talking about khaleeji music.

A.S.: Yes, exactly. Because it's dance music. It's different from the kind of slow and monotonous music of North Africa.

B.E.: Interesting. Compared with music from say Lebanon, khaleeji has more African rhythms. Right?

A.S.: Right. The Gulf music. Definitely. And now, they have even appropriated some of the hip-hop and rap styles.

B.E.: I was going to ask you about the situation in Darfur, and its origins. I know this is a very complicated story, and we probably don't have time to go through it in detail. But let me just feed back to you on the way Omer Ihsas told it to me, and get your comment.

Omer said that the conflict really goes back a lot further than the way it's usually described in the press accounts. It has to do with the whole struggle for political power and power over resources, and the kind of unequal development that you were talking about. He spoke about a road that was long promised, and money that was taken from the local sugar industry. That money was supposed to go to build this road, but the road was never built, so local people weren't getting the money and they weren't getting the sugar, and they weren't getting the road. And all of this was building up resentment. And then there was the fact that Darfur was associated with an opposition party in the context of the 1989 coup. Omer also said that since that time, the government has been fearful of Darfur unity, so they did whatever they could to try to co-opt a few members from each ethnic group in order to sow discord among the different ethnic groups so that it would be very hard for them to come together.

Omer recalled that when he was young, there used to be celebrations where all of the region's ethnic groups came together and shared each other's traditions. All the different tribes in the region would relate to each other through culture, but that now that can't happen anymore, because there's been so much animosity created. The way he described it, this has all been sown by outsiders, and specifically by the government, to undermine unity. So you have this problem of unequal development, and political disenfranchisement complicated by all of this new division among tribes, and this is what has created the environment where you could have a conflict that we see now. Is there anything you would correct in that general characterization?

A.S.: No, I think he's quite on the mark. But I would say it even goes further. It is all part of this pattern of unequal development, and in fact, the Darfur-based movement started in the 1960s. They were all demanding equal distribution of economic resources, economic development and so forth. And the use of this proxy war, is a tactic that was used by the Sudanese government in the south, and in the Nuba mountains, by exploiting ethnic differences, and arming one group against the other. That is definitely the case in Darfur. I would also say one of the main reasons that triggered the whole thing was the signing of the peace agreement between the SPLA and the government, in the sense that many groups felt that they were left out; this agreement was basically focusing on North-South issues and ignored their situations. That was probably one of the immediate factors that ignited the recent conflict.

B.E.: And that agreement was signed in?

A.S.: Well, the final agreement was signed in 2005, although the negotiations started much earlier. Even as the negotiations were taking place, it became very clear that the accord was focusing mainly on the north-south issue.

B.E.: So that was a spark into this very volatile situation.

A.S.: Exactly.

B.E.: I know we're running out of time, but let me just ask you this one last question. Do you think that cultural expressions, and in particular music, can play a meaningful role bringing together these diverse factions and helping to build a stronger sense of Sudanese unity? Do you think that's possible, or is that just a romantic dream?

A.S.: No, I think in the Sudanese context, where you have these deep cleavages and conflicting notions of identity, indeed music can play a role. I think in order to bridge the gap, both sides—those who embrace Arab identity and those who do not—have to recognize their common heritage. I think music is one area where they can find this common heritage. For instance, northern Sudanese need to recognize the African cultural traits in their heritage, especially in the area of music. So I do think music and popular culture can play a role in terms of the debate about Sudanese culture and identity.

B.E.: One artist I spoke with said that it was easier to achieve this sort of unity in diaspora settings than in the country itself. He also said it would mean more if it happened back in Sudan.

A.S.: I certainly agree with that. The Diaspora exposes Sudanese to things that they have not been exposed to before, such as the whole discussion about identity, race, and color. Living in the United States, for example, definitely forces one to think about all of these issues of race and color. So I think in that regard, it is a useful experience for many members of the Sudanese Diaspora. I think the reason that debate is stifled in Sudan is due ti the political environment. It is just beginning to open. In fact, there is a book about Sudanese immigrants in America by a scholar named Ruqayya Abu Sharaf.

B.E.: Thanks. I will look for that.

Click here for more information on the 2008 Sudan Festival of Music and Dance.