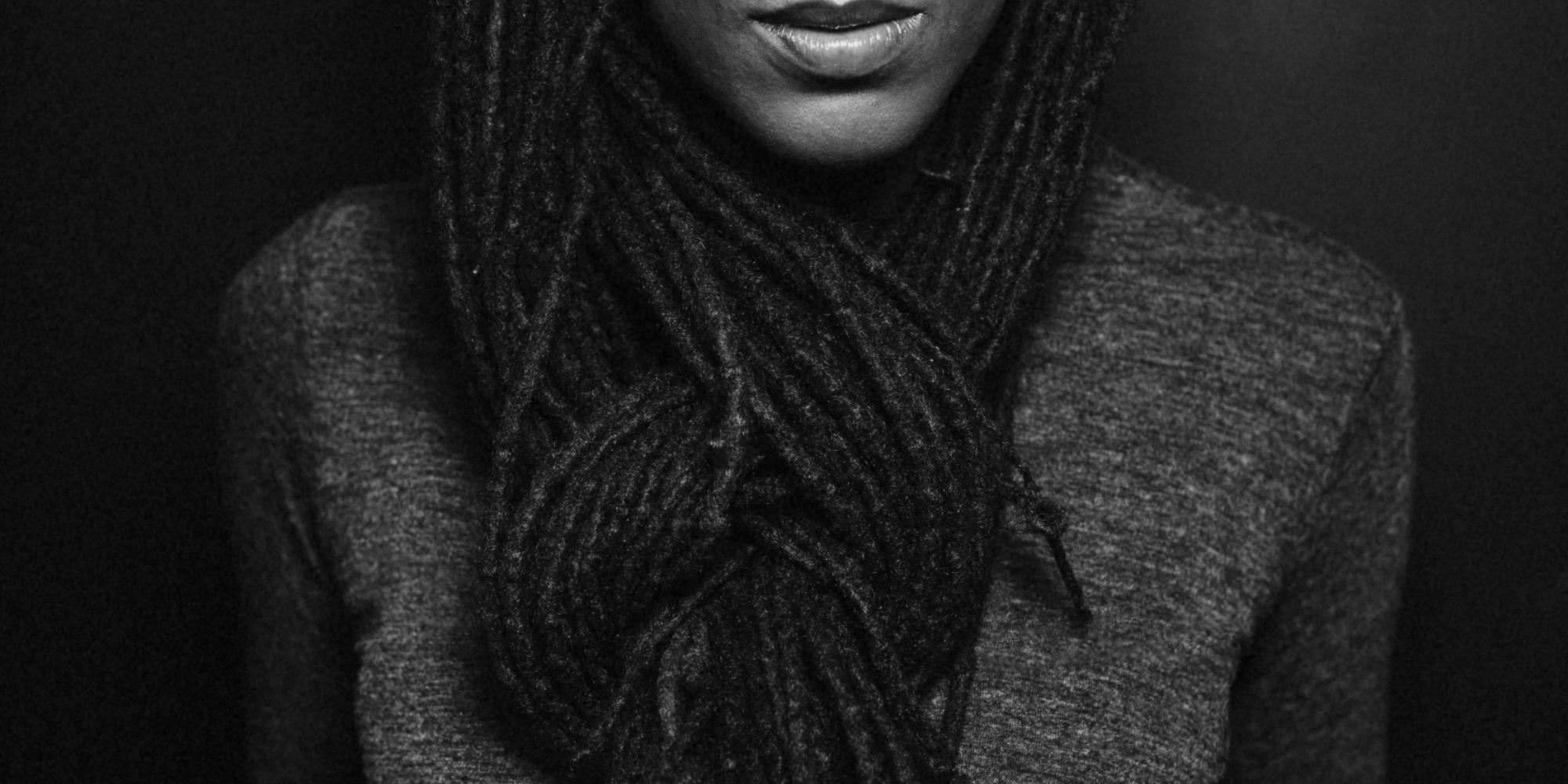

Akua Naru’s lilting raps against drums and a blend of hip-hop, jazz, afropop, and world music make me feel a divine reverence. Her songs are healing and honest. Akua can never run out of material to create, because she is working towards goals greater than individual success in a capitalist world. An African-American woman hailing from New Haven, Connecticut, she not only speaks of black power and women’s beauty, but she embodies it with a relaxed, purposeful way of being.

Akua recently released her third album, called The Blackest Joy. It was the product of a transition in her life; she had been thinking about the lives of slaves and was disheartened by “these videos as they’re being posted online” demonstrating the discrimination and oppression today, 400 years after slavery ended. “Of course, you retraumatize,” she said. With The Blackest Joy, she reflects on black joy “as a form of resistance, as a political act, as a force in and of itself.” By writing about black joy, Akua herself was able to taste how joy feels: “when I swallow it, when I gobble it down, when I’m housing it here in my body.” The album is an intimate look at the black joy she cherishes, as well as a political statement.

Based in Cologne, Germany, she has sold out multiple concerts since beginning her international tour earlier this year, and she will perform in Senegal at the Afropolitan Nomad Festival in July. Aside from her success with music and poetry, she has spoken on academic panels about African spiritualities and hip-hop, and teaches women’s empowerment workshops. Musical and intellectual circles have recognized Akua’s work. She recently won the Nas Fellowship, a grant to fund scholars and artists who demonstrate exceptional abilities and scholarship related to hip-hop. With this fellowship, she will develop the Keeper Project, an “online multimedia archive for black women hip-hop artists.” She calls herself a “keeper of the tradition,” of which there are many: someone who chronicles and preserves black lives and culture. This is especially important in such a globalized society, in which pop music and culture can dominate over traditional ones. Akua combines historical facts and experiences with her experiences in the modern world. She is using the platform she has now as an artist to honor African ancestors who were enslaved and mistreated, and who should have had just as much of a voice as she does now.

Since she was a child, the black female forces she admired in her community and in church strengthened Akua with their passion and determination. An avid reader, her New Haven community encouraged her to continue telling the stories that she wanted to hear. Her poetry evolved to become musical organically, once she started performing spoken word and reciting to a rhythm. Now, she encourages others to find their paths. She structures her empowerment-focused workshops based on the needs of attendees, “sometimes, with black women healing circles, [or] talking about hip-hop workshops, talking about sexism in the music industry.” Although the audiences she has encountered are receptive and admiring, she knows there are those who believe “Harriet Tubman was free and led us to freedom, but [Akua] can’t rhyme in sync.” Akua is only one of the “black women,” who she describes, that “[can] come in and kill [dominate] the cipher real quick.”

With Akua’s ability to reach mass audiences that lifelong poetry-writing practices and natural talent have given her, she will continue to write subversive lyrics and give voice to those who came before her.

Related Articles