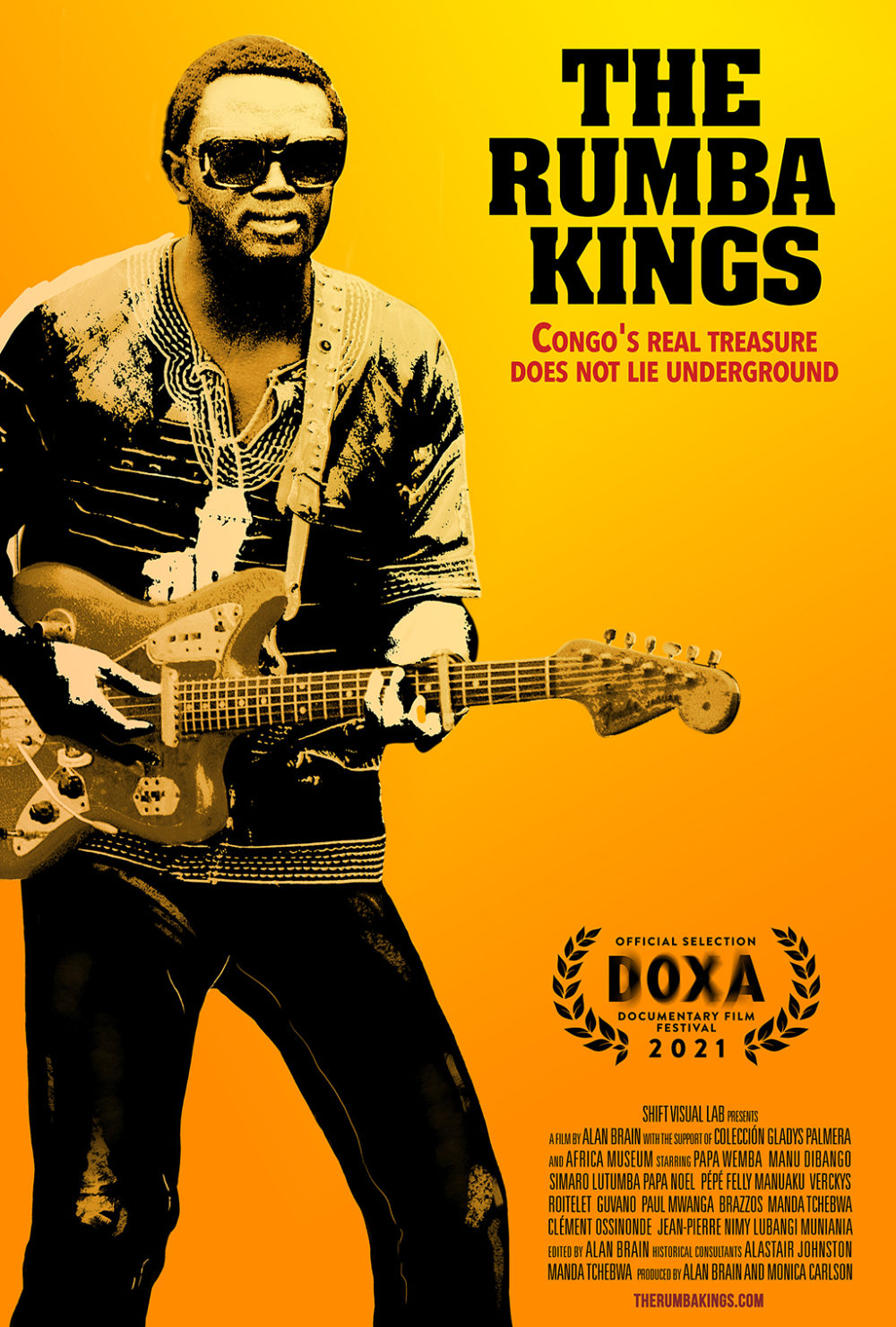

Alan Brain is a Peruvian-American filmmaker currently living in Rabat, Morocco. None of that would suggest that he has spent much of the last decade making what we believe to be the best film about Congolese rumba to appear yet: The Rumba Kings. It’s a rich account of the birth and emergence of this quintessential African music genre, focusing on three principle figures, Grand Kallé, Dr. Nico and Franco. The story is told by Congolese people who were there for the experience, and the footage is to die for. Afropop’s Banning Eyre got a sneak preview of the film, which premieres at the DOXA Documentary Film Festival on May 6, 2021. Banning reached the filmmaker over Zoom, and here’s their conversation.

Banning Eyre: Alan, It is great to reach you. To start, what brought you to Morocco?

Alan Brain: My wife works for a diplomatic agency of the United States. We were living in Washington D.C. and she was assigned overseas. We had two options, Nepal and Morocco. We decided on Morocco. It's a cool and very peaceful place. We arrived here in April 2019. Almost two years ago now. We lived through the pandemic here.

I'd love to explore Morocco more. Nice music too.

Yes. Different. A different type of music, but it's very nice.

Well, as a longtime fan of Congo music, I really enjoyed your film. Kinshasa was actually the first place I ever went in Africa, back in 1987.

Really?

Yes indeed. Matonge was in full swing. Music 24/7. I got hooked on the place from that moment. And Congo music was hugely important in the early years of our program, because at that time, as you know, it was the most popular music in Africa.

Oh yeah. For sure.

So I have deep interest in your subject and was mightily impressed with the film. It’s the best thing I've seen yet on Congo music.

Thank you! That means a lot to me.

So let's hear how it happened. Tell us a little bit about yourself, and then how you came to make a film about Congolese music.

I started in filmmaking as an editor in Perú, working on several prime time journalistic shows like 60 Minutes. I also worked with some Peruvian Hollywood directors editing films and TV series. That was my life up until 2006 when a friend of mine told me that he was going to go to Congo to work for the United Nations. They needed somebody that could work on documentary filmmaking, doing short vignettes about the work of the United Nations mission in Congo. So my friend Oscar went to Congo, and after a year of coordinating and a lot of paperwork, I was in Congo in 2007. It was a tough decision because I knew I had to commit for at least four years. I ended up staying much longer.

In Congo, my work in the beginning was basically promoting the work that the United Nations was doing on human rights, rule of law, and other related areas. Slowly, I started gravitating towards the local culture, the people. I started getting in touch with Congolese sculptors, painters, musicians.

The United Nations had a weekly TV show in Congolese TV, on RTNC, which is the national television of Congo. We started doing a little cultural segment of five to 10 minutes for that show. We managed to squeeze into that show a little touch of local color. It took some engineering, but the United Nations accepted it. And really, it was a hit.

On a parallel note, at that time I made a rock band. I was the vocalist. It was an amateur rock band with a friend of mine from Kosovo who played guitar, another Peruvian on rhythm guitar, and some Congolese musicians. Now some of those Congolese musicians are famous, like Rodriguez Guez Vangama, the main guitarist of the band, who is playing in Brussels now. You can see Rodriguez in this video. And there's the drummer Paulin Lukombo who is now playing in Paris.

We made concerts with this band for a year or so, and then we switched to salsa. We transformed this rock band that was doing covers of Cream, Crosby Stills and Nash, and Jethro Tull, into a salsa band. We noticed that the people were connecting more with the one Latin-salsa song we played, the song about Che Guevara, “Hasta Siempre Comandante.” We turned this song into a kind of dancing guajira, and it was the best moment of our concerts. We realized that's what the people wanted and we became a salsa band, with 14 musicians, two trombones, two trumpets, two saxophones, timbales, etc.

We were playing covers of “Brujería” and “El Menú” by El Gran Combo, “Buscando Guayaba” by Rubén Blades, “Todo Tiene Su Final” by Héctor Lavoe and other salsa songs. I was the main singer of the band and we had three amazing Congolese singers. We became good friends. And one day one of them said to me, "Alan, you don't know anything about Congolese music. You see how it is here now. It's tough. We can’t even find a proper amplification system for the band. But just 20 years ago, we were the kings, man."

I said, "What?"

“Yes,” he said, "Let me give you something," and he gave me a CD of Lokua Kanza. And he also gave me a compilation with a mix of songs of African Jazz and OK Jazz. That was a door for me, and well, it never stopped. I fell in love with Lokua Kanza, big time. And then I fell in love with the music of Dr. Nico and Grand Kallé and OK Jazz. For me it was a revelation.

That's a great story. Now, as I understand it, a lot of the U.N. mission was focused in eastern Congo, but it sounds like you were in Kinshasa.

Yes. Mainly because the heart of the mission during all those years was in Kinshasa. Why? Because there were a lot of political negotiations that needed to happen in Kinshasa while the United Nations peacekeepers were in Goma, in the east.

So you probably went back and forth.

Sure. I went to Goma, Bukavu, Bunia, Kisangani, Matadi... I went to many regions in Congo. Congo is a lovely place.

Lucky you. I never got much out of Kinshasa, and I know that musically, things are very different in the east. But let's stay with Kinshasa where you're getting immersed in the music scene. So from what you're telling me, I'm sure you became quite aware of the Cuban connection with Congolese music. Tell me about your discovery of that.

Well, I have to go a little bit back. So basically, I just had started listening to Congolese rumba. I was listening to it in my car every day. I became crazy about it. It was my bread and butter and my party music. So, just right around that time, Tabu Ley died [Nov. 30, 2013]. I knew by then who Tabu Ley was because I had bought and read Gary Stewart's book, Rumba on the River.

Great book. Kind of the bible of Congolese music.

Yes, a truly great book. Since I knew who Tabu Ley was, I went to film the three days of mourning. I have all of that in my archive. I didn't use it in the film, but I filmed it all.

And on the second day of mourning – and this is completely crazy – I was next to the coffin of Tabu Ley and this guy came by and he kind of really took his time with Tabu Ley. I saw him and thought there has to be someone here who really knows more about Congolese music. But who? Then this guy, he looked at me. Then he passes by the camera and asked me, "Can I help you with something." In French. By this time I spoke French. I learned French in Kinshasa.

C’est important.

Tres important. Without French, I would not have been able to make the film. So he asked if he could help me and I said, "You know, I'm trying to find somebody who's connected with this rumba community and who could help me meet some of these stars that I know are still alive." And he said, "Oh, let's talk, because I know them all." So he took me outside and we started talking. He became a kind of a local fixer/producer for the film. He put me in touch with everyone. His name is Aime Bassay. He became a good friend of mine. We spent the next year working together, and well, through him, I met Brazzos, Roitelet, Petit Pierre and many other musicians.

And, going back to your previous question, the Cuban connection was right there, because Aime introduced me to this guy named Kuka Mathieu. Kuka Mathieu was a singer of one of the later formations of African Jazz. He composed a very famous song called “B.B. 69.” We found him walking in a neighborhood of Kinshasa. We were in the car and we saw him on the corner. Aime said: "Stop the car! Kuka, come.” And Kuka comes and starts singing songs in Lingala. He was completely happy and full of energy.

When he heard that I was from Latin America he started singing songs in Spanish. and I'm thinking, “I know that song, from my father." He started singing “El Yerberito” by Celia Cruz

Kuka knew all these Latin songs. And he said there is a huge Latin connection with Congo. He also started singing “El Manisero.”

Of course. “The Peanut Vendor.” I think every band in West and Central Africa plays that song.

But I didn't know it at that time.

So this experience at the funeral of Tabu Ley in 2013 leads you to these people, and that's where you get the idea to make this film?

Long story short, the idea of the film probably happened in two moments. The first moment was when I watched an American documentary film called Playing for Change.

Yes. That's where musicians around the world collaborate together on covers of famous songs. Beautiful stuff.

Yes, made by Mark Johnson. I fell in love with that. I said, “Wow. The sound is amazing. How did he get that sound?” There were the microphones on camera. I loved it. I said, “One day if I could do something with that same energy, it would be amazing.” And while that film was still on my mind, I met Brazzos and Petit Pierre. Those were the first two Congolese rumba legends I met, before Kuka. And they told me about the African Jazz's trip to Brussels for the negotiations for the independence of Congo in January 1960. I had read a little bit about that in Gary Stewart's book.

Like I said, it's the Bible, especially in English.

So, Petit Pierre and Brazzos told me the story in detail. Brazzos used to play rhythm guitar for Franco in OK Jazz, but when he went to accompany Grand Kallé in 1960 to play at the Table Ronde political negotiations for Congo's independence in Brussels, he was somehow cornered into playing double bass. The team that traveled to Brussels to play for the politicians was Joseph Kabasele "Grand Kallé" (vocalist and orchestra director), Vicky Longomba (vocalist), Roger Izeidi (maracas), Petit Pierre (percussion), Mwamba Dechaud (rhythm guitar), Nico Kasanda "Dr. Nico" (solo guitar), and Armand Mwango "Brazzos" (rhythm guitar). The band had two rhythm guitar players but no double bass player. Brazzos knew that Dechaud and Dr. Nico, who were brothers, had an amazing synergy that should be left intact. Brazzos decided then to learn to play double bass on the fly to fill that role. And so, Brazzos told me that he spent many hours practicing with the double bass and dealing with the bass strings that were harder to manage than the guitar ones. He also told me that his fingers were, at some point, bleeding and that sometimes, during that trip in 1960, he had to put tape in his fingers to be able to play.

They, Brazzos and Petit Pierre, were telling me all this and I thought, "Really? You traveled with the delegation of politicians of your country to Brussels when you were what? Sixteen years old? And you didn't play bass before? You learned to play there? And then you played for the politicians in Brussels and composed this song? [‘Independence Cha Cha’]” “Oh my God. Why is nobody telling this story?”

So that was the second moment when the idea of making a film came to me. I started thinking, “O.K., this story has to be told. I have to do my best. It might take years, but I have to start now..”

So that's how it started.

Yes. And in the end, we were able to tell the story in a new way. The trip of the African Jazz to Brussels in 1960, despite being really epic and very important, has never been properly documented. In 2020, together with Congolese scholar Manda Tchebwa, we managed to rebuild, with evidence from photos and newspapers, most of the timeline of that amazing trip. We were able to pinpoint the exact day when the song "Indépendance Cha Cha" was composed and the day it was played for the first time ever. We also cleared some inaccuracies such as that the African Jazz played at the opening of the Table Ronde negotiations. That is not true. The orchestra left Leopoldville days after the Table Ronde had already started and they never played at the place where the negotiations happened.

Most important is that we discovered that this trip was way bigger than we all knew before. The band did more than 60 concerts not only in Belgium, but also in France and the Netherlands. The results of this research will be published in the next Planet Ilunga record label compilation about Surboum African Jazz, which includes a text I wrote about this, and also in a book that Manda Tchebwa is publishing this year about the life and times of Grand Kallé.

That is fascinating. So when you started figuring out how to put this film together, you had to pick certain artists to focus on. The stars are Franco, Dr. Nico, and Grand Kallé. Tabu Ley is mentioned, but he's not in the frame as much. Why did you choose to focus on these three?

That is a complicated question. From my point of view, in the narrative structure of the film and the period it describes, Tabu Ley opened the time frame too much. There is no doubt that Tabu Ley is as important for Congolese rumba as Franco, Dr. Nico and Grand Kallé, But, to properly include Tabu Ley in the film, we would need another 20 minutes. And in my view, that would make the film too long and the core narrative would lose momentum.

Interesting. So once you got started, how did you go about researching?

Very early in the game, let's say three or four months after meeting Brazzos and Petit Pierre, I was being introduced to all these amazing Congolese rumba stars such as Bikunda, Roitelet, Simaro or Pepe Felly Manuaku. And I was interviewing them on film. My interviews were really long. I have interviews of more than two hours with each one of them. At that time, I did not know what the exact core narrative of the film was, so I was trying to collect as much information as I could.

You had a lot to learn.

Exactly. I was reading my books about Congolese rumba. I was preparing for each interview with detailed notes. But I knew that I had to capture the most I could, because I didn't know what I was going to need. I knew that I didn’t want to make a historical documentary that was just completely academic neither do a documentary that was a genealogical tree of the musicians. I wanted some of that Playing For Change documentary spirit. There had to be songs and a strong narrative.

I guess Wendo Kolosoy had already passed away by the time you were working. The last time I was in Congo was in 2002 working on a late recording for Wendo. That's where I met the guitarist Bikunda and the saxophone player Maproco, both in your film. And subsequently there was a film about Wendo, which no doubt you have seen.

On the Rumba River.

Yes. It's an interesting film, very much focused on Wendo himself. But I read in your press materials that you did not want to make a film that focused on the daily lives of musicians, their struggles and hardships and so on. You wanted to focus on the music. Talk about how you came to that decision.

I guess that decision came to me organically. Surely, I filmed a lot of footage that clearly portrays the daily hardship of the musicians in the film. For some time, a year or two, I started building the documentary with that lens. I was trying to convey the awful truth, which is that most of these musicians have made great records and were continent-wide musical stars, but due to the deep flaws of the copyright system in Congo, and other structural problems, they have died in poverty. It's heartbreaking and unfair.

So, I put together some sequences of the film with that approach, but it felt wrong to me. I felt that by focusing on the struggle I was not really paying homage to the legacy of these musicians nor was I letting the audience connect properly with their music. I reviewed many documentary films about Congolese and African music, and most of them focused more on the struggle of the musicians than on the music. And when watching these documentaries, I was offered very little space as a viewer to learn about the music and appreciate the musicians’ skills and talent. Some of these documentaries would show you a musician having breakfast two times in the same film, or they would show you the musician walking through the neighborhood. Then, on the other side, the same film may not have even two musical performances, with high quality sound and video, that properly portray the stardom and/or talent of that musician.

I decided then that I wanted to flip this common narrative. These musicians were nothing short of rock stars and they deserve to be shown in all their glory. It was clear to me that the film needed to focus on the incredible music and the amazing talent of these Congolese rumba stars.

Having said that, those hard realities are in the film, they are in the backgrounds of the interviews, in the stock shots, etc. I have not hidden anything. I just decided to keep the spotlight where it belongs, on the music.

As Congolese rumba connects to audiences beyond the African continent and beyond the circle of fans of Congolese music, there will be a space to start that other conversation and dig into copyrights issues, corruption, and other systemic problems that musicians face in Congo and in other African countries. A conversation about how unfair is that many of these musicians were not able to properly live out of their music, even though they were famous in Congo and the whole African continent, and what we can do about it.

That’s very interesting and valid I think. So then, I guess your big challenge was to find material, especially footage of performances that you could use. I was amazed at the things you found. There is so much wonderful footage and imagery in your film. How did you find it? I imagine this is a long story, but give me some highlights.

When I realized I was going to do this film and was going focus on these musicians, I still didn't know what the story was going to be, but I started to worry about three things. Photos. I needed a ton of photos. Video. I needed films. But also, proper recordings. There were some reissues, but I didn't have much. So I thought I had to start buying records. One of the things I did for the records was to copycat an idea from Samy Ben Redjeb of Analog Africa.

Yes. I know him. He's done amazing work.

Somebody told me that Sammy went to Kinshasa and started buying records by putting flyers up around the city. So I did the same. I bought about 300 records in Kinshasa. And I was buying them not only for the music, but for the photos, the photos on the covers.

So eventually, I made a list of the videos I needed to find. I spent almost a year in Kinshasa looking for videos every week by every means possible. Somebody would connect me with somebody. "Look I have an old tape of this Franco concert that is better than the DVDs. Do you want to buy it from me?" But the thing is, I was buying the image, but I wasn't buying the licensing rights. I knew this was going to be a twisted process. I was going to pay for the privilege of having the copy of the video, and later, down the road, I was going to deal with the copyrights.

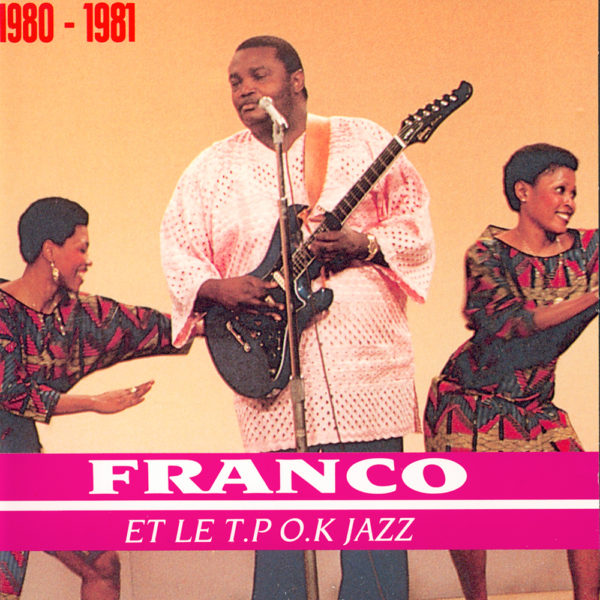

Let's talk about the black and white footage. The video where Franco is playing "Alimatou," and the video of "Matata Ya Muasi Na Mobali Ekoki Kosila Te." Both belong to a series of concerts that Franco did in the studio of Telezaire, and they were originally in color. But what happened is they had these three-quarter inch master tapes that started to die because of the humidity. And somehow, at one point, the tapes stopped playing in color. I got some good quality copies of that performance. Somebody found an old tape and we managed to get a machine and copy that tape to a digital file. It was a bit of “Alimatou”, a bit of “Matata Ya Muasi Na Mobali Ekoki Kosila Te” and a bit of "Nioka Abangaka Mpe Moto." Although, we did not use the video of the last one, we expect to release it as a bonus track when the film gets released on DVD or Bluray.

For Kallé it was sort of the same process. We have a video of Grand Kallé singing “Parafifi” and “Kelya.” We didn't use “Kelya” in the film but we have it in a good quality also.Then for Dr. Nico, we were actually lucky to find one Nico concert which was filmed by Spanish TV. That was properly licensed and copied, that was somehow easy. But still, it took years to find that video, to know that it existed. We also have in the film a performance of Zacharie "Jhimmy" Elenga playing acoustic guitar. That footage came as a courtesy of the Royal African Museum in Belgium. They were kind enough to let me include that in the film.

But those other black and white videos, the one with Franco, and the one with Grand Kallé, the ones that we found in Kinshasa, they went through several months of restoration. Those videos had a better quality than what you see in YouTube, but they were not 1080 HD at all. The size was tiny. For the first years, I was using them at a small size in the center of the screen surrounded with black bars because if I resized them, they looked really bad. It was just three years ago that artificial intelligence software allowed me to upscale them.

That's fascinating. A new technology. Because they look quite good.

I upscaled them and then I sent them to Photoshop. I spent months retouching these videos, frame by frame. I have some videos of that.

Yes I'm sure you have quite a “making of” reel. Boy, I really look forward to seeing this film again. I didn't take notes the first time. I just sat there amazed.

Let me tell you about the Zaire 74 footage. For the first year, let's say 2014, when I was still in Kinshasa--because I left in August 2014—I knew that there were two videos that I needed to pursue with all my force. One was that Zaire 74 footage. I didn't know who had it, what company had the rights, nothing. And the other one was a performance of Verckys with his Orchestra Veve playing for Idi Amin in Uganda. This was shown in a documentary by Barbet Schroeder (General Idi Amin Dada: A Self Portrait, 1974). I got in touch with the production company. It took me months to find the right person. But from the Barbet Schroeder side, we never found anything else. They said, "We don't know." What is in the film is what we have. That's it.

But then on the Zaire 74 side, I actually found the people who had the footage. And they sent me the whole concert of Franco. They sent me the footage from all the cameras. They were really kind to me. They said, "We love your project.” One of the people who was involved in this and to whom I owe a lot is Jeffrey Levy-Hinte the director of Soul Power, who was also the editor of the Oscar winning documentary When We Were Kings.

That's why there were many cameras there, because they had brought this great crew there to film the big American stars. It's wonderful that you were able to get that video.

I was in Kinshasa when I received the footage. I saw the whole concert of Franco! I edited the whole concert with all the cameras just to see what was the best part. Because I knew that this footage was very expensive and I was only going to be able to license some minutes. I needed to license the best. And the only way was to edit it all.

Wow. That’s a treasure. Alan, it is as such a pleasure to speak with you about this film. It is so powerful and well contextualized. And it was nice to see people I've met over the years, Manuaku, Simaro, Papa Wemba, Bikunda and our friend Lubangi Muniania, who has been a contributor to our program on a number of occasions.

I think the honor is mine to be here with you. I actually discovered Lubangi through your program.

Oh really? That's nice.

I didn't know Lubangi. I was searching for a Congolese scholar who could be part of the cast of experts along with Manda Tchebwa, Clément Ossinonde and Jean-Pierre Nimy. And I needed somebody like Lubangi. Because he's very strong in his knowledge about the music. So I listened to your show and I read the interviews you have with him. And then I became a fan of your show. So, the honor is completely mine.

Well, that is kind of you. It sounds like you’ve had a lot of help from the rumba community.

Absolutely. The rumba community has made this film possible. Without them, we wouldn't have been able to finish. Their energy and enthusiasm kept us going. It is also important to mention the contribution of Alastair Johnston and Manda Tchebwa. Alastair Johnston's help was so important, even from early in the creation of the project, that when things started to take shape with the film, we decided that Alastair should be a consultant producer. And since then, Alastair's contribution to the film has been invaluable in many ways: the selection of songs, the search to find the best version of those songs in vinyl or a CD), the direction of the narrative, aesthetic matters, etc.

In that same sense, I have to mention the enormous contribution of Manda Tchebwa, a renowned Congolese scholar and a dear friend of mine, author of more than 12 books about Congolese rumba, who is the main interviewee of the film as well as the historical consultant. Manda was able to bring all his knowledge, a lot of love and passion for Congolese rumba, and a happy and upbeat energy to the film. I met Manda in 2013 in Kinshasa when I interviewed him for the first time about Congolese rumba. At that time, in his office, I listened to him in awe, completely mesmerized, while he was telling me all these stories about the early record labels of Congolese rumba, and the bars where this music developed. The passion and love for the music was literally flowing out of Manda's words. That day, I knew that Manda's knowledge and love for the music were extremely important for the film.

So I guess we have one more question, how can people see this film? I know there is a festival in May, but beyond that, how will people be able to see this?

Our Facebook page for the film has 20,000 followers. These are really passionate people and we love them all. We are working behind the scenes to get the film into as many film festivals as we can. We will publish all these opportunities to watch the film in our website and in our Facebook page. Our goal is that everybody has a chance to see the film as soon as possible. After that, we'll try to get distribution. Unfortunately, the distribution is going to be complicated because the copyrights for some of the footage in the film are expensive. So in order to put it on Netflix, there is a high ticket that we have to pay. But we’re working on that too.

Well, good luck with all that, and do keep us posted.

Before we go, I have to tell you one more thing. You asked about the Cuban connection. We actually removed a Cuban sequence from the film. We removed it six months ago. You see, the film had a sequence where we actually interviewed a scholar from Colombia and a scholar from Cuba, talking about Benny Moré and Arsenio Rodriguez. We made a sequence to prove this connection. There is solid evidence that these two famous Cuban musicians had clear Congolese roots. Arsenio Rodriguez even has a song where he says, "I am from Congo. I am not Rodríguez, I am not Fernández. Maybe I am Lumumba, maybe I am Kasavubu.” We spoke with friends of Arsenio and they all told us that he always said, "I am from Congo."

And the case of Benny Moré is similar. Benny spent his childhood at Casino de los Congos, a sort of temple for traditional Congolese religion in Cuba. Benny probably learned there how to approach music. We had everything. We had the photos. We licensed the music. But in the end, we felt that this sequence was a detour from the core narrative, so we had to cut it.

That sounds like a film unto itself. I hope we get to see it one day.

Thanks a lot for the opportunity of being here to connect with your audience. And thanks for supporting music. Your work is amazing. You have done so much for a lot of music. We—and I mean we—owe you a lot.

Well, thank you. We’re all part of a big community and we have to support each other. I look forward to speaking again soon, and best of luck with those festivals.

We shared our new trailer recently on our Facebook page, and the reaction has been huge, we have more than a 1,000 shares. We have received tons of comments from passionate fans and supporters. You can see that here.

NOTE: The world premiere will take place online at the DOXA Film Festival in a few days, on May 6. The film will be available to stream online from May 6 to 16. The projection will be geo-blocked in Canada and can be accessed here.

Related Audio Programs