Blog October 28, 2016

Ali Faiq on Rwayes Heritage and Re-Creation

While in Agadir, a city on the Southwest coast on Morocco, Afropop producer Jesse Brent caught up with Ali Faiq, a legendary figure of Amazigh music and fusion in Morocco. Former members of Ali’s previous band, Amarg Fusion, have gone on to form other well-known groups in Agadir: Inouraz and Ribab Fusion. Jesse spoke with Ali in his office in Dcheira, a suburb outside of Agadir, about Ali’s new album with Amarg Experience titled Isktitn. You can hear two tracks off that album on our new program, “Moroccan Music Today: Re-Examined Past, Innovative Future.”

Jesse Brent: To start, can you give a little introduction of yourself?

Ali Faiq: My name is Ali Faiq. I was the leader and founder of Amarg Fusion, which was a very well known band in Morocco. Now, I work with another band called Amarg Experience. I try act as a bridge between the generations of the youth today and old rwayes musicians. Rwayes is a musical genre that exists in the south of Morocco, and unfortunately is disappearing because so many of the members of this art are disappearing little by little. So, I am sure that my grandchildren and the generations of the future will not find it or they will find this genre uprooted and disoriented. I discovered a repertoire that was hidden in a library in France where there are names of rwayes [rwayes can be used interchangeably for both the style of music and musicians who play it] that nobody–not even professionals–knew. So, I said, “Why not revive this unexplored heritage?” First, I played with rwayes musicians and after with young musicians, and I brought them together in a project called Isktitin. Isktitin means “memorial.” Memorial of names and also memorial of the texts that were not known by anyone. The purpose is to promote this heritage and this genre of music to the world. It’s between memorial and re-creation. Re-creation because I have this tendency to not do the same thing [as on the old recordings]. But I tried to show people that young people can play their way and old people can play their way. And their authenticity can create a product that will at least start to renew these songs in this repertoire.

So, you are mixing these old songs with other styles?

Not exactly other styles. But, I am interested in sonorities. The sonorities of traditional instruments are unique, and we mix those with contemporary sonorities with bass, drums, piano. At the same time, there is this authenticity with the instruments and backing vocals of rwayes. It’s truly new and old at the same time. That’s our philosophy.

Rwayes is an Amazigh style of this region. Is it just here in the Souss region?

At the geographic level, it exists in the valley of the Souss, Massa, and the region of Essaouira, and also the region of Marrakech near Ouarzazate. Rwayes was created in the cities. The two most well known cities in the south of Morocco are Tiznit and Marrakech. So, there were always two schools of rwayes–one in Marrakech, especially in Jemaa el Fnaa, and the other in Tiznit–the old city of the era. It’s an art that is professional. It’s not like ahwach, where everybody participates in collective songs. Rwayes is an urban music that began, I believe, in the 18th and 19th centuries. It is rooted in the history of the Amazigh of the Souss. This is an intellectual music. It is a music that has its own language, that has its own notes, styles, techniques, and methods of playing.

And what are the instruments of rwayes?

There are string instruments. The ribab is a one-stringed violin. And also there is the outar. Then there are percussion instruments, like a metallic instrument called naqqus, and also the bendir. Rwayes are in some way troubadours and they voyage with their music. Not just in the Souss, but in all of Morocco–even in the north. They used to travel all the way to Oujda. They were singing news and proverbs, whose themes were about everyday life.

Did the poetry of rwayes speak about political situations of their time?

They spoke about everything: politics, religion, everyday life, advice, values. It touched everything.

How many musicians normally play rwayes together?

Normally, between five and 15 musicians. But now, sometimes 50 or 60 rwayes play together at once. For me, to make this kind of symphony takes a lot of time to integrate modern techniques, arrangements and harmonizations.

Can you tell me about some of the songs on the album?

For the album, there are five songs that I found at the Bibliothèque Nationale in France. I heard the sixth song, “Agwlif d izimmer” one day when I was sitting with some rwayes, and somebody started playing this song. I asked him, “What is that?” And he told me, “It’s an old melody that a rwayes who is deceased now sang in the ‘60s.” I asked him, “Do you know the words, the lyrics?” He said to me, “Unfortunately no.” I tried to keep this song in my memory and to find lyrics to go with it. The lyrics on the album were written by a friend of mine, a poet named Said id Bennaceur. There are two images in the song. There are bees who create honey, and think that they are loved by people. But on the contrary, people chase the bees away with smoke to get the honey. There is also the image of Eid Al-Kabir, when sheep are slaughtered. The song “Abelljenel” was sung by two singers in the same period. So, we know it is part of the heritage. The rule is that when we find several singers interpreting the same song at the same time, that song belongs to an older era. We don’t know who the composer is. The theme of the song is desire with several images.

Can you translate a little bit?

“I want to drink, but the spring is far away. I want to meet people who are very important in my society, but they are also far away. I need to find a gazelle, but I am afraid to hunt. I want an orange, but the owner of the orange tree doesn’t want me to take one.” There are obstacles to desire. They are metaphors.

Is it a metaphor about love?

About love and about the social need for respect.

Did you find the lyrics to the songs in the library?

No, I tried to decipher them from the recordings. It has taken me five years now. I kept the melodies, but in my own way. I changed some of the phrasing a little bit. So, always, it is not an imitation. If I imitate, it will produce nothing new. I cannot imitate the emotions sometimes because they demand authenticity. I have included a sample of the original recording of “Ayajddig.” This was played by women originally.

A man sang and the women played instruments?

No, in this era women sang and played instruments. The song is about a flower hidden in the desert. “Where do you hide when it’s very very hot?” For my version, the tempo is different.

Were men and women speaking to each other in these songs?

Yes, in ahwach and also in rwayes. Sometimes, the songs are debates between generations, between a man and a woman, or between a black and a white person. Unfortunately, for us now, this was not good to do this–even on the level of men and women, we enter into a context that is a little pejorative. But happily, now there is a change of mentality–that we must respect women. We must respect differences between one race and another, between one religion and another.

Can you tell me about some of your projects before this new album?

Before Amarg Experience, I played with Amarg Fusion, and before that Dounia Amarg. The first big concert I played was in 2005 at the Boulevard Festival in Casablanca. I never thought that music would lead me to something like that.

What does this word “Amarg” mean?

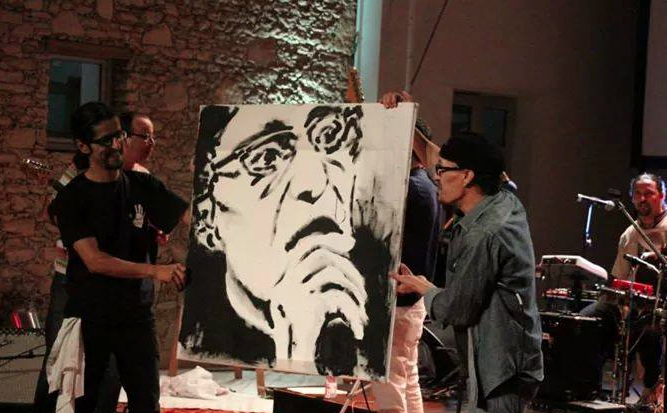

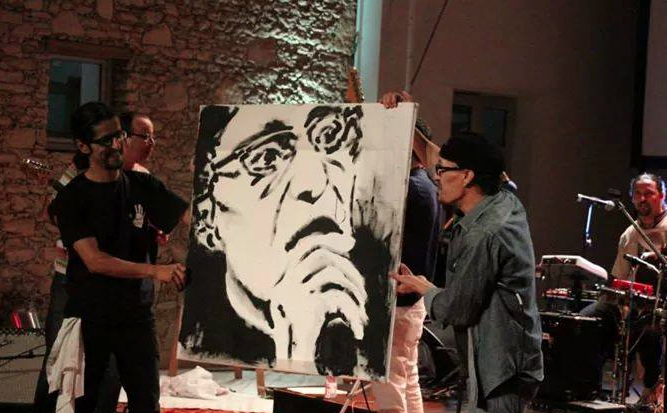

“Amarg” is sung poetry. Before this album, there was an album called Tirra S Ikwlan, which means “writings in colors.” It’s an homage to painters because painters always think about musicians. They draw rwayes. But musicians never think about painters. I saw someone who was painting musicians and he asked me, “What do you do for us?” That touched me. I wrote a song about how here in Morocco we don’t value painting as a means of expression. Before, I remembered during my childhood that there were no paintings in the house because it was haram [forbidden], but now there is a change of mentality about art. This was my first album after Amarg Fusion broke up.

Are there many painters here in Dcheira?

Yes, there are many painters. Here in Dcheira, there are many self-taught artists. These are great artists. I am always touched by them. In 2013, I was invited to give a concert at the Institut Français of Agadir. I sang and an artist painted. He made four paintings during the concert. It was extraordinary. His name is Younes Speed.

For this album, were you also bringing together young and old artists on the same songs?

Yes, they played on the same songs, but not in the same way. There will be no generational conflict if we understand that each generation has its differences. Even if we have differences, we can respect them and see what we can do together. For example, even on the level of clothes, in Morocco, there are people who don’t accept if you wear a baseball hat or jeans. Now, this is beginning to not exist anymore. There are conservatives who say, “We must leave things as they are,” and there are innovators who change things. This creates conflicts. For me, I can accept that you have your djellaba and that you play your music. I have no problem, but you have a problem that you cannot accept me. In the beginning, this was very difficult. Sometimes the form hides very important things–qualities and potentials. But sometimes form evolves more than content. So to change this mentality takes time. Now, I see that young people are not interested in the culture. There are so many young people who are uprooted. They are not Western; they are not African; they are not Moroccan. They are truly lost. To bring together young and old people together–this gives me a great inspiration musically. The styles are different, but they complement each other.

Did you always have these ideas in your music?

I have a philosophy of sharing with others. And I always had this habit of respecting differences. I was like this before music–trying to be more humanist. It is my parents who educated me like this. My parents told me to respect others. For example, when we ate together and somebody who had nothing to eat came and said, “Please.” He could come in and he would be the first to eat. This is a great humanitarian value. It’s not racial or religious. These are the values of the south of Morocco.

Before, I remember in the ‘70s, people didn’t have doors. You could leave your things in the street and nobody would take them. Now, it’s no longer like that. You could leave your bag over there in the street. You could wait two hours and return and find it. Unfortunately, society has changed. Human values have disappeared. For example, my music is nothing for people here. I have sung in my language for almost 30 years. But if there is a foreigner who comes and sings in their language, everybody says, “Oh, somebody who has come from abroad! He sang! What is he doing?” I feel that there is a self-contempt. We must be confident in ourselves. This reflects a complex toward our culture, our heritage, our language. We must be proud. Because if we don’t value this music then it will disappear.

Have you played with musicians from other parts of the world?

Yes. I was working on a project called Enono Anya and I went to New Caledonia for five days of concerts. Before this, I never knew that there were Kanaks. These are people from New Caledonia. I discovered this culture. It is a minority culture that is completely different from ours. They are polyphonic. They play on a bamboo and a guitar with vocalists. Our world is completely different–pentatonic music with the outar and the ribab. We tried to create a repertoire with 11 songs. Before, when the project was proposed to us, everybody said, “It’s impossible for you to play together because you are so different.” That is the strong point–we base our music on differences. And we touched the public. We played some rwayes songs and some songs that come from their culture. Also, in Cabo Verde, I played with a Brazilian named Sebastian Notini–it was a beautiful adventure. I am sure that I have been enriched through these meetings with great musicians. We are not eternal–only through others are we eternal. It’s what we transmit to others–that’s what assures our duration in this universe. It’s for that reason that we exist.

For this album, were you also bringing together young and old artists on the same songs?

Yes, they played on the same songs, but not in the same way. There will be no generational conflict if we understand that each generation has its differences. Even if we have differences, we can respect them and see what we can do together. For example, even on the level of clothes, in Morocco, there are people who don’t accept if you wear a baseball hat or jeans. Now, this is beginning to not exist anymore. There are conservatives who say, “We must leave things as they are,” and there are innovators who change things. This creates conflicts. For me, I can accept that you have your djellaba and that you play your music. I have no problem, but you have a problem that you cannot accept me. In the beginning, this was very difficult. Sometimes the form hides very important things–qualities and potentials. But sometimes form evolves more than content. So to change this mentality takes time. Now, I see that young people are not interested in the culture. There are so many young people who are uprooted. They are not Western; they are not African; they are not Moroccan. They are truly lost. To bring together young and old people together–this gives me a great inspiration musically. The styles are different, but they complement each other.

Did you always have these ideas in your music?

I have a philosophy of sharing with others. And I always had this habit of respecting differences. I was like this before music–trying to be more humanist. It is my parents who educated me like this. My parents told me to respect others. For example, when we ate together and somebody who had nothing to eat came and said, “Please.” He could come in and he would be the first to eat. This is a great humanitarian value. It’s not racial or religious. These are the values of the south of Morocco.

Before, I remember in the ‘70s, people didn’t have doors. You could leave your things in the street and nobody would take them. Now, it’s no longer like that. You could leave your bag over there in the street. You could wait two hours and return and find it. Unfortunately, society has changed. Human values have disappeared. For example, my music is nothing for people here. I have sung in my language for almost 30 years. But if there is a foreigner who comes and sings in their language, everybody says, “Oh, somebody who has come from abroad! He sang! What is he doing?” I feel that there is a self-contempt. We must be confident in ourselves. This reflects a complex toward our culture, our heritage, our language. We must be proud. Because if we don’t value this music then it will disappear.

Have you played with musicians from other parts of the world?

Yes. I was working on a project called Enono Anya and I went to New Caledonia for five days of concerts. Before this, I never knew that there were Kanaks. These are people from New Caledonia. I discovered this culture. It is a minority culture that is completely different from ours. They are polyphonic. They play on a bamboo and a guitar with vocalists. Our world is completely different–pentatonic music with the outar and the ribab. We tried to create a repertoire with 11 songs. Before, when the project was proposed to us, everybody said, “It’s impossible for you to play together because you are so different.” That is the strong point–we base our music on differences. And we touched the public. We played some rwayes songs and some songs that come from their culture. Also, in Cabo Verde, I played with a Brazilian named Sebastian Notini–it was a beautiful adventure. I am sure that I have been enriched through these meetings with great musicians. We are not eternal–only through others are we eternal. It’s what we transmit to others–that’s what assures our duration in this universe. It’s for that reason that we exist.

For this album, were you also bringing together young and old artists on the same songs?

Yes, they played on the same songs, but not in the same way. There will be no generational conflict if we understand that each generation has its differences. Even if we have differences, we can respect them and see what we can do together. For example, even on the level of clothes, in Morocco, there are people who don’t accept if you wear a baseball hat or jeans. Now, this is beginning to not exist anymore. There are conservatives who say, “We must leave things as they are,” and there are innovators who change things. This creates conflicts. For me, I can accept that you have your djellaba and that you play your music. I have no problem, but you have a problem that you cannot accept me. In the beginning, this was very difficult. Sometimes the form hides very important things–qualities and potentials. But sometimes form evolves more than content. So to change this mentality takes time. Now, I see that young people are not interested in the culture. There are so many young people who are uprooted. They are not Western; they are not African; they are not Moroccan. They are truly lost. To bring together young and old people together–this gives me a great inspiration musically. The styles are different, but they complement each other.

Did you always have these ideas in your music?

I have a philosophy of sharing with others. And I always had this habit of respecting differences. I was like this before music–trying to be more humanist. It is my parents who educated me like this. My parents told me to respect others. For example, when we ate together and somebody who had nothing to eat came and said, “Please.” He could come in and he would be the first to eat. This is a great humanitarian value. It’s not racial or religious. These are the values of the south of Morocco.

Before, I remember in the ‘70s, people didn’t have doors. You could leave your things in the street and nobody would take them. Now, it’s no longer like that. You could leave your bag over there in the street. You could wait two hours and return and find it. Unfortunately, society has changed. Human values have disappeared. For example, my music is nothing for people here. I have sung in my language for almost 30 years. But if there is a foreigner who comes and sings in their language, everybody says, “Oh, somebody who has come from abroad! He sang! What is he doing?” I feel that there is a self-contempt. We must be confident in ourselves. This reflects a complex toward our culture, our heritage, our language. We must be proud. Because if we don’t value this music then it will disappear.

Have you played with musicians from other parts of the world?

Yes. I was working on a project called Enono Anya and I went to New Caledonia for five days of concerts. Before this, I never knew that there were Kanaks. These are people from New Caledonia. I discovered this culture. It is a minority culture that is completely different from ours. They are polyphonic. They play on a bamboo and a guitar with vocalists. Our world is completely different–pentatonic music with the outar and the ribab. We tried to create a repertoire with 11 songs. Before, when the project was proposed to us, everybody said, “It’s impossible for you to play together because you are so different.” That is the strong point–we base our music on differences. And we touched the public. We played some rwayes songs and some songs that come from their culture. Also, in Cabo Verde, I played with a Brazilian named Sebastian Notini–it was a beautiful adventure. I am sure that I have been enriched through these meetings with great musicians. We are not eternal–only through others are we eternal. It’s what we transmit to others–that’s what assures our duration in this universe. It’s for that reason that we exist.

For this album, were you also bringing together young and old artists on the same songs?

Yes, they played on the same songs, but not in the same way. There will be no generational conflict if we understand that each generation has its differences. Even if we have differences, we can respect them and see what we can do together. For example, even on the level of clothes, in Morocco, there are people who don’t accept if you wear a baseball hat or jeans. Now, this is beginning to not exist anymore. There are conservatives who say, “We must leave things as they are,” and there are innovators who change things. This creates conflicts. For me, I can accept that you have your djellaba and that you play your music. I have no problem, but you have a problem that you cannot accept me. In the beginning, this was very difficult. Sometimes the form hides very important things–qualities and potentials. But sometimes form evolves more than content. So to change this mentality takes time. Now, I see that young people are not interested in the culture. There are so many young people who are uprooted. They are not Western; they are not African; they are not Moroccan. They are truly lost. To bring together young and old people together–this gives me a great inspiration musically. The styles are different, but they complement each other.

Did you always have these ideas in your music?

I have a philosophy of sharing with others. And I always had this habit of respecting differences. I was like this before music–trying to be more humanist. It is my parents who educated me like this. My parents told me to respect others. For example, when we ate together and somebody who had nothing to eat came and said, “Please.” He could come in and he would be the first to eat. This is a great humanitarian value. It’s not racial or religious. These are the values of the south of Morocco.

Before, I remember in the ‘70s, people didn’t have doors. You could leave your things in the street and nobody would take them. Now, it’s no longer like that. You could leave your bag over there in the street. You could wait two hours and return and find it. Unfortunately, society has changed. Human values have disappeared. For example, my music is nothing for people here. I have sung in my language for almost 30 years. But if there is a foreigner who comes and sings in their language, everybody says, “Oh, somebody who has come from abroad! He sang! What is he doing?” I feel that there is a self-contempt. We must be confident in ourselves. This reflects a complex toward our culture, our heritage, our language. We must be proud. Because if we don’t value this music then it will disappear.

Have you played with musicians from other parts of the world?

Yes. I was working on a project called Enono Anya and I went to New Caledonia for five days of concerts. Before this, I never knew that there were Kanaks. These are people from New Caledonia. I discovered this culture. It is a minority culture that is completely different from ours. They are polyphonic. They play on a bamboo and a guitar with vocalists. Our world is completely different–pentatonic music with the outar and the ribab. We tried to create a repertoire with 11 songs. Before, when the project was proposed to us, everybody said, “It’s impossible for you to play together because you are so different.” That is the strong point–we base our music on differences. And we touched the public. We played some rwayes songs and some songs that come from their culture. Also, in Cabo Verde, I played with a Brazilian named Sebastian Notini–it was a beautiful adventure. I am sure that I have been enriched through these meetings with great musicians. We are not eternal–only through others are we eternal. It’s what we transmit to others–that’s what assures our duration in this universe. It’s for that reason that we exist.