Think “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin-to-Die Rag” by Country Joe McDonald in 1967--a broad satire unleashed at America’s Vietnam War. Transpose that to Cameroon, and a satire aimed at the Eurocentric legacy in independent Africa: “Zangalewa.” Performed by Cameroon’s Golden Sounds in 1986, the song became an anthem across Africa, crossed the pond to Latin America, and ended up with its core message inverted in Shakira’s multiplatinum hit “Waka Waka: This Time for Africa.”

The Golden Sounds (Jean Paul Zé Bella, Dooh Belley, Luc Eyebe and Emile Kojidie), oddly enough, were active members in Cameroon’s presidential guard. The song’s lasting success stems largely from its very infectious military-march rhythms. The lyrics, due to the multilingual nature (up to 600 languages) of Cameroon, skip around between French, Douala, Pidgin English, Fang and perhaps Ewondo. Of course, there are “left, right, left right” marches, but then the song is really about the grievances of the ordinary recruit: lousy pay, bad food, punishing training, etc. And they also really lay into the brass: their fat and abusive drill instructors who scarf down a yummy assortment of sugary beignets while threatening to shave recruits’ heads and send them to prison.

Music video caught on quickly in Africa in the ‘80s. The full meaning of “Zangalewa” was actually realized in the remarkable video, which superimposes the band lip-syncing the song over Cameroonian military parades, apparently using bluescreen. The band members are wearing uniforms stuffed with pillows to create comedically large bellies and behinds, with “big belly” repeated in the lyrics. At one point a band member whirls around and appears to be hectoring a vast formation of soldiers assembled down below him.

The satiric look takes three very significant steps further: the band members are wearing pith helmets, brandishing bâtons swagger, or swagger sticks, and are in half whiteface. Bâtons are totally obsolete. They come from ancient times, Napoleon thought they were essential, and they resurfaced as hot items for Generalfeldmarchallen in the Third Reich. Swagger sticks, too. They were largely abandoned after World War I, and only egomaniacs like Patton used them after that.

The pith helmet you see on “Zangalewa”’s record label was headgear the colonial powers issued to their soldiers in the “hot tropics.” Neither swagger sticks nor pith helmets have anything to do with Cameroon’s military. So, along with the whiteface, “Zangalewa” becomes a protest against Cameroon holding onto too many pernicious colonial practices. Swagger sticks, pith helmets, and especially whiteface, strongly signal collaboration. After a nation is subjugated by a foreign power, that’s really the worst crime you can commit. For example, Iraq.

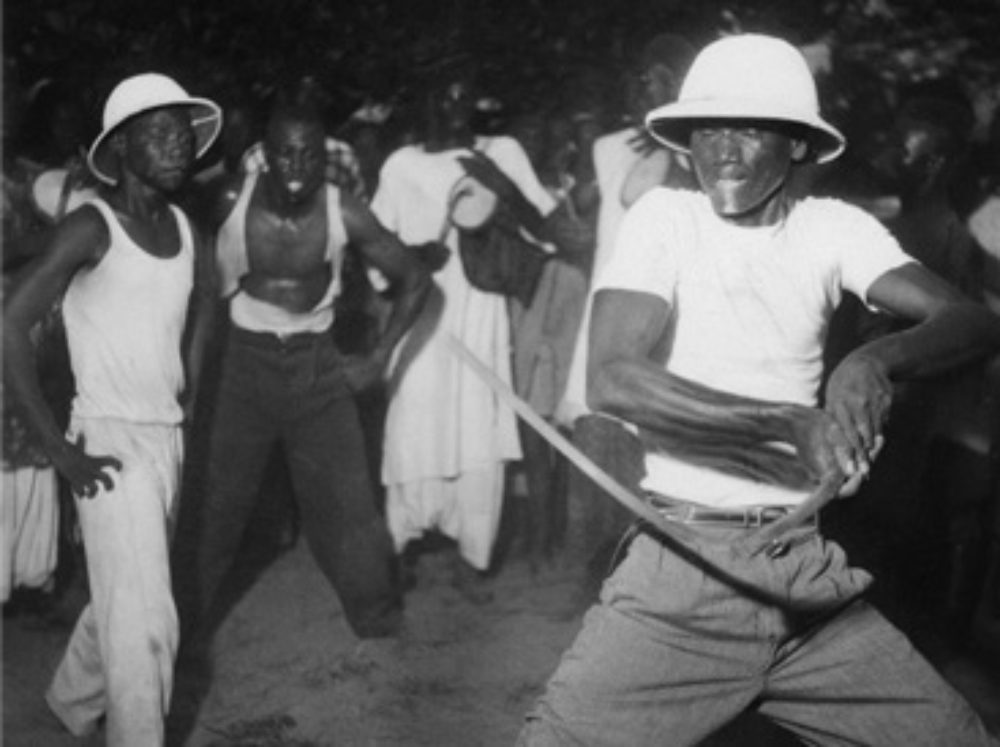

This is nothing new. French New Wave documentarian Jean Rouch’s most controversial film Les Maitres Fous showed us how African culture included ritualized satire of colonial masters. What did the Nigeriens pantomiming their oppressors in Rouch’s film wear on their heads? Pith helmets.

The infectious beats of “Zangalewa” were covered across Africa, from South Africa, to Nigeria, to Cote’d’Ivoire, to Ghana, to Senegal (Momar Gaye and Zaman’s being the best. Marchable, and also very danceable. Across the Atlantic, it would be heard in Suriname, the Dominican Republic, and especially Colombia.

Blacks in Cartagena, Colombia responded enthusiastically to African styles including soukous and highlife in the 1980s, developing their own champeta style. “Zangalewa” was a natural there, recorded by Los Condes. But Latin American covers of “Zangalewa” were retitled “El Negro No Puede,” with lyrics about a Black man who cannot sleep, presumably impeded by nonstop partying. No soldiers in videos for these covers, either – just women writhing in lingerie, ubiquitous in early MTV days.

Trevor Noah, host of The Daily Show, really irritated the French two years ago when he said “Africa won the World Cup,” because Les Bleues were predominantly of African heritage. That being said, no African country has ever won the World Cup, and the entire continent really craves this prize. When Senegal’s Teranga Lions team beat France in 2002, all of French West Africa went bonkers.

No smaller controversy erupted earlier when FIFA announced superstar Shakira, backed by the South African multiracial fusion band Freshlyground, would perform the latest cover of “Zangalewa,” entitled “Waka Waka (This Time for Africa).” The song is beloved across Africa, so why isn’t an African artist performing it? Shakira is half Lebanese, her name means “grateful” in Arabic, and she uses Arabic scales--but that was not close enough. Like the “telephone game” in which children in a circle whisper something into the ear of the child sitting next to them, the original historical perspective and satiric thrust of “Zangalewa”’s lyrics and video were long gone in a blur of lingerie by the time Shakira got to the song. Her lyrics do not question authority in the military. Quite the opposite. From “You're a good soldier” to “You're on the front line,” they nakedly equate soccer performance with an unquestioned and unquestionable military duty.

Despite mixed reviews, “Waka Waka (This Time for Africa)” inevitably went multiplatinum, the second success for the diva since her “Hips Don’t Lie,” and its video, with Shakira in skimpy, fringy, “African” dancewear, also topped the charts. Surviving members of Golden Sounds in Cameroon did not receive a penny from this, but they did not sue Shakira for plagiarism; one bandmember had admitted the chorus came from Cameroonian “sharpshooters who had created a slang for better communication between them during the Second World War.” A rumor circulated that the lyricist behind “El Negro No Puede” was suing Shakira, but he later denied it.

dj.henri is a New York City DJ who has performed at the Apollo Theater, B.B. King’s, Symphony Space, and elsewhere. He is also the creator of radioafricaonline.com.