Andy Morgan is a journalist and author with deep experience in Mali. He attended the very first Festival in the Desert in 2000 and was involved in the festival for many years after that. Andy managed the Tuareg band Tinariwen during its international rise in the early 2000s. His 2013 book, Music, Culture and Conflict in Mali (Freemuse) provides one of the most lucid descriptions of Mali’s 2012-13 crisis and its effects on musical life available in English. Andy is working on a larger book about the Sahara, which we eagerly anticipate. Visit http://www.andymorganwrites.co... for more.

Afropop’s Banning Eyre met with Andy when he came to New York to launch the 2016 film They Will Have to Kill Us First, which Andy co-wrote. The two sat down for a conversation about Tuareg music and history in preparation for the program “Hip Deep in Mali: The Tuareg Predicament.” Here’s their conversation.

NOTE: For more on the situation in Timbuktu, visit Timbuktu, Land of Peace and Culture, a blog in English by local correspondent El Hadj Djiteye.

Banning Eyre: Let's start with history. The Festival in the Desert took place in a special time. Tuareg rebellions go back at least to the formation of Mali in 1960, but in the 1990s, the Tuareg made peace with the government. I remember seeing that huge mountain of arms being burned in Timbuktu. Tell us what happened in the '90s to make it possible to have those festivals.

Andy Morgan: The actual rebellion of the 1990s was very brief, only six months long. And it ended in an initial peace deal, a sort of cease-fire really, called the Tamanarasset Accords. And then came the negotiated National Pact, which was the basis on which all the next decade's worth of promises were founded. That was signed in 1992.

But the peace was negotiated in a time of great political turmoil in Mali as a whole. It was the end of the dictatorship of Moussa Traore, and the beginning of entirely new regime. There was a military coup led by Amadou Toumani Toure, ATT, who then became president, and who very graciously handed over pretty swiftly to a democratic process, which elected Alpha Konare.

The problem is that the will to actually make peace in the north was much weaker in Bamako than it should have been. Certain politicians were making promises, signing deals with the Tuareg, with Iyad Ag Ghali the leader of the MPA (Popular Movement for Azawad). Others were saying the government shouldn't deal with these guys at all. They should just be brought into line. The people who were making promises and signing deals were out of office a year or so later, so a new group of ministers who may have had a completely different point of view were coming in. If this National Pact had been respected, history would have been very different. Because in fact, when the next conflict broke out in 2006, the demands were pretty much word for word the demands that had been made and supposedly honored in the National Pact.

So instead of everybody knuckling down and saying, "O.K., we signed the National Pact. Let's make it work," what happened was that northern Mali degenerated into ethnic war between the Songhoi and the Tamashek, between different Tamashek factions, between the Arabs and the Tamashek. It became a nightmarishly complex kind of chaotic situation of small groups fighting each other.

Andy Morgan and Banning Eyre at the Festival in the Desert (Barlow 2003)

Andy Morgan and Banning Eyre at the Festival in the Desert (Barlow 2003)

So the development promised in the National Pact—roads, schools, hospitals—never really happened. I heard a lot of comments in our interviews in Mali to the effect that money was actually sent, but that it was eaten—bouffé!

Yes. You're talking about the period from ‘92 up to 2011. And yes, money was sent, and was bouffé by everyone along the way, including supposedly responsible Tuareg leaders. But you see, what happened in 1992 is very, very significant, because the Songhai set up a militia, what they would call a self-defense force called the Ganda Koy, and the Ganda Koy started attacking Tuareg civilians, basically. It developed into a very nasty civil war, with a lot of attacks on innocent civilians, people who were noncombatants.

And for sure, the MPA and the various other Tuareg factions also did things they shouldn't have done against Songhai and Fulani and other citizens. But what really riles the Tuareg is that they absolutely 100 percent convinced that the Ganda Koy was set up with the help of the Malian army, and that this whole ethnic conflict was purposely exacerbated by elements in Bamako. They didn't want to concede to the Tuareg. What they were promising in 1992 was basically a certain amount of decentralization. That's always a big issue in Mali. How much power can the regions of the country have in relationship to the center? It's a huge sort of existential question in Mali. And it's not just the north. It's everywhere.

Beyond that, there were the developmental issues—roads, communications, clinics, education. The language of education. Should the kids in the Kidal region be educated in French? In Tamashek? Should they be educated, 'God forbid,' in Bambara? That was a big issue. And then there were other cultural issues, like the representation of Tamashek language and issues on national TV. A big issue is security. Who is responsible for securing the north? Should it be the Malian army with a bunch of southerners? Or should it be local people? I'm really summing it up in a very swift way.

That’s both helpful and appropriate.

But the problem is that this degenerated into a very nasty conflict. There was one massacre that still really, really rankles among the Tamashek of the North. The Ganda Koy massacred a village of Kel Essouk, maraboutic [clerical] families, not far from Gao. These things were absolutely terrible things to live through, very difficult to assimilate, and very difficult to forgive.

What was motivating this militia?

I think it was motivated on two levels. The first is the honorable level—purely self defense. It was this idea that during the rebellion, there were a lot of insecurities. There were Tuareg elements coming down south from Kidal and Anéfis , or Ménaka. And you know in a war situation, you take what you need. Some people were stealing animals, destroying crops along the river—that kind of thing. Any Ganda Koy person will say it was a self-defense force. “The Malian army was just not operating very efficiently, so we needed to defend ourselves.”

But the other, darker side is that it was an attempt to divide and rule, led by Bamako. It was also an attempt to say that any solution in the north cannot be just Tuareg driven. The Songhai needed to be politically and militarily powerful in any settlement that may be happening.

Do you think there's some truth to the idea that the Malian government was complicit in this?

I don't think it was a strategy that Parliament debated. But I think there were certainly people in the military, and certain politicians, who were very happy that the Ganda Koy was doing what the Malian army should have been doing, but was kind of incapable of doing.

Wow. Let's go back to basics here. What is Azawad?

Azawad is a concept. I mean, all nations are built on concepts finally. Mali is a concept. So Azawad is another concept. It’s the north. Basically, Mali looks like a boat with the sail slightly tipped over. And if you draw a line where the sail starts, everything north of that is Azawad.

There are endless debates about historical justification. A lot of southern Malians will say Azawad has never existed. It was never a country. There was a region called Azawad, sort of an administrative region during the French colonial times. The word Azawad comes from the Arabic word. I think it’s the singular of Sudan, “the land of the blacks.”

You’ve described Azawad in terms of geography, not ethnicity. That was a key point a lot of the interviews we did in Mali. Some still refer to the 2012 uprising as a "Tuareg rebellion." But others are careful to say, "No, no, no. This was not a Tuareg rebellion. This is about the people of the north.” In otherwords, Azawad is not about ethnicity; it’s geographical.

Absolutely. It’s useful to go back to 1992. The rebellion that was fought in ‘91 was multiethnic. It involved Arabs and Tuareg from the north of Mali, who then fell out with each other and formed rival groups. The Songhai weren't really part of it. In 2011, you had all these Malian Tuareg returning from Libya. Some of them had been living there since the rebellion of ‘91. Some had been there since the 1980s. They came back with a certain amount of weaponry, and before doing anything, they sat down and talked. They planned what they were going to do, and one of the big themes that was being talked about is that this rebellion should be a rebellion of all the people of northern Mali.The problem is that that ideal never really became a reality on the ground.

They always will cite this guy Mahamadou Djeri Maïga, a Songhai who was the vice president of the MNLA [National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad]. So they would always say, "Look, we've got Mahamadou Djeri Maïga. We are multiethnic." The truth is the senior officials in the MNLA are about 80 percent Tuareg, with a splattering of Arabs, maybe one or two Songhai. So wasn't the real coalition that should've been, and personally I think that's a real shame. Because when you talk to the Songhai and get past their anger at the Tuareg for making life so difficult and wanting to split up Mali—which 95 percent of Songhai don't share—what they want for their region in terms of development is very, very similar. So if they had actually managed to sit down and say, "Let's do this together. Let's find a way of working together," they might've got much further.

Fadimata Walet Oumar (DIsco), speaking out at peace forum (Eyre 2016)

Fadimata Walet Oumar (DIsco), speaking out at peace forum (Eyre 2016)

In think that most people recognize that the original rebels did not share the jihadist agenda, but there is this question of how it all began. One Songhai musician said to me unequivocally, "Of course it was a Tuareg rebellion."

I mean it was a Tuareg rebellion. I think the MNLA are disingenuous when they say, "No, no, no, were fighting for all the people of Azawad. “ I mean, in a sense they are. Bless my Tuareg friends; they feel that it's their destiny to fight the cause of other people who are too unwarrior-like to fight. And that's kind of slightly their relationship with the Songhai. And that goes back into history, because part of the symbiotic relationship is that certain Tuareg factions in history became defenders of Songhai communities against often other Tuaregs who were raiding them in the great era of raiding, before the French.

Last night we watched this film you co-wrote, They Will Have to Kill Us First. There’s a powerful scene where the Tuareg band Tartit and the Songhai singer Khaira Arby perform together in Timbuktu, after the crisis. It’s a powerful symbol of interethnic solidarity, isn’t it?

I was there, and it was extraordinary, just an elating experience. But you know, Songhai and Tuareg musicians have had a relationship for a long time. It's not as if they don't know each other, they don't talk to each other. And the symbol of that is takamba music from Gao. Takamba music is just the absolute heartbeat of Gao. It is Songhai Tuareg music, played together, and in a way a symbol of that symbiotic relationship that we've been talking about, which is very much real.

If you really want to read about this, there's one fantastic book, which is written by two guys, Charles Grémont and André Marty. Les Liens Sociaux au Nord-Mali. Just through interviews with local people, it builds a picture of how all these ethnic groups relate to each other. And what's really clear is that the Songhai and the Tuareg, they probably fought like cats and dogs, I imagine, at the time of the Songhai Empire, and everything was a matter of power. And then the Tuareg took over Timbuktu… But I would say for a good century and a half before 1992, they were pretty much living in peace with each other. I mean, there would've been some raiding and pillaging. The Tuareg were real bad boys for that. You cannot get away from the fact that part of their culture in history was to just to descend and take what they needed. It was an aspect of life.

That's interesting. I spoke with historian Gregory Mann, who emphasized the devastating effects of the droughts of the early 1970s. They killed so much of the livestock in the north, and put enormous pressure on life, pressure that had been largely missing or decades before that. I think that's an important thing to understand in terms of how things got so heated in our time. Don't you think so?

Absolutely. But it goes back further than that. There were terrible droughts before. What I've been studying for my book very intensively the last two months is the upheavals in the southern Sahara during the First World War, between 1911 and 1918. You might say that’s the real first Tuareg rebellion. 1963 is the second. I mean, I'm being a bit facetious. But all of that was on the back of drought as well, and famine, and terrible harvest. That was a major element in the Gao region.

One of the things I've always felt about Mali compared with other places I've visited and written about, is the way people from different ethnic backgrounds know each other quite well. And that promotes tolerance. I’ve always thought this was a point in the favor of the griot tradition. But I saw another fact of it in Segou on our recent visit. The Caravan for Peace presented an evening of largely Songhai and Tuareg music for the locals. And despite all the history we've been talking about, you had a Tuareg band get up in front of a largely Bambara public, most of them young, and they were all cheering and clapping and dancing.

Andy Morgan

Yeah, I think that is unique in Mali. Mali has the griot tradition. It also has this amazing thing called senankouya, what the French call cousinage. This is where certain ethnic groups base their relationship on the fact that they can take the mickey out of each other, freely, and therefore defuse emotions. And it's fine. It is pre-set up for them to do that, and it's not dangerous. It's O.K. So I think that is a major contributing factor.

The question I always ask myself is why was the conflict in 2012 not more violent than it was? All in all, there were probably about 1000 casualties, 1500 casualties, maybe a couple of thousand? For an occupation that lasted 10 months, and then there was a war. If you compare that to Liberia or Sierra Leone… I mean every death is a tragedy. Every single one causes immense suffering, not to denigrate that. But why wasn't it more violent? Why weren't they just ripping each other apart?

And I think that's to do with senankouya. It's certainly to do with the griots. The griots are diplomats in many ways. The griots are masters of the word, and you need to control your words in order to get what you want, to be a diplomat. I think all of that plays into the mix.

The way people react to Tuareg music is very interesting. I don't think Tuareg music was on the map for people until Mali became a nation. It still isn't for a lot of Southerners I would say, probably. But the biennales and the semains de la jeunesse—this whole system that grew up under Mali’s first president, Modibo Keita, and then under Moussa Traore. They did really remarkable things. It was like the Eisteddfod in Wales. Something that started at the village level, and then there was a structure of competition went all the way to the national level. And when you got to the national level, you would have a troop from Sikasso who were supposedly the best singers, the best dancers, the best musicians, even actors. They had all sorts of categories, and they’re in competition with the equivalent from Kidal or Gao. And they would all spend loads of time together in Bamako, eating, sleeping. Because the competition lasted weeks and weeks. And I think that gave everyone a sense that, "Yeah, there's all this other music." They liked it.

Bassekou Kouyate, Andy Morgan Ibrahim Ag Youssof

Bassekou Kouyate, Andy Morgan Ibrahim Ag Youssof

Then there is a more recent song by Tinariwen. That song had some success on Malian TV. Like you, I was in Segou at a show, and the place was rammed full with Bambara people, going bananas for that song. They absolutely loved it. It really really surprised me to be honest as well. And it made me think that Malians get angry. There's a lot of discontent in the country. But somehow they value their culture so much. They are always going to consume and enjoy culture, and they don't really ask too many questions about where it comes from. Something like that.

Tinariwen in Brooklyn (Eyre 2012)

Tinariwen in Brooklyn (Eyre 2012)

O.K. So let’s talk about Tuareg music. Let’s start with this term used for the modern Tuareg guitar music, ishumar. What is ishumar?

Ishumar is the Tamashek-ization of the French word chômeur, or unemployed. Tuareg youth left the northeast of Mali in the late '60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s, to get jobs, to find a fortune, to escape hopelessness really. And when they were hanging out in X or Y Algerian or Libyan town, they were like a bunch of clandestinos. They were these ragged, young, angry, 'dangerous undesirables.' They would hang out on the edge of town, and sleep under trees and in dried riverbeds. Some of them would get jobs in town, really menial jobs, tending someone's garden, or doing a bit of masonry or carpentry or something like that. And they would earn money and they would pay for everyone.

Often the police would come and check up on them. And they would go, “Hey you, chômeur!” Unemployed. Good for nothing. And they changed it into a badge of pride, which I love. It's like punk. “You punk!” Punk. Punk. “Great, we’re punks." They started calling themselves Ishumar. “We are the Ishumar. We're the unemployed. We are proud of what we are. We annoy polite society, but we are proud of ourselves." That's what ishumar is.

Interesting. And this became the name of the new guitar music, right?

Yes, because we’re talking about the late '70s. These are kids really, teenagers at the time. The only musics they had known back in northern Mali were all the traditional forms of Tuareg music—tinde, iswat, shepherd's flute, and various other traditional forms. What they started doing very, very young was making these plastic can guitars. They get a plastic container, stick a length of wood onto it, get some bicycle brake wire, and start playing guitar.

The way I've understood it, they started listing to rock music, but it’s difficult to say exactly what other forms of music. It was also country & western, and North African, Egyptian and Sudanese--oud music. So the idea is you need something with strings, something that looks a bit like a guitar. There was also the tehardent, which is like the ngoni, but Gao style. And of that kind of got thrown into the mix. And then they started listening in the late '70s to Santana. They love Santana. They loved Dire Straits. Dire Straits is the favorite band of all Tuareg guitarists from the 1970s.

Tinariwen, Brooklyn, (Eyre 2012)

Tinariwen, Brooklyn, (Eyre 2012)

We actually did a segment on Afropop Worldwide about the Tuareg fascination with Dire Straits. We ended the segment with a shout-out to Mark saying, “If you want to make peace in the north of Mali, come and play concert there. That's the one thing that would unite all the Tuareg.”

They would love that. They would go absolutely bananas if he came. So anyway, they were playing all that. But meanwhile, going back decades, even centuries, there's been a very strong tradition of poetry, Tuareg poetry. I've been recently researching Charles de Foucauld, the French priest who basically created Tamanrasset. [1858-1916, beatified by Pope Benedict in 2005.] Foucauld made it his life's work, before he was assassinated, to collect Tuareg poetry and writing. He compiled this amazing collection of Tuareg poetry, and you definitely see the roots of Ishumar poetry, in that time, three-quarters of a century before.

So based on that foundation of poetry, in the 1970s, due to the conflict, the exodus of young people out of northern Mali, and due to the drought, which was, as you say, really, really shocking, it was sort of ground zero. Up to 80 percent of the herds in certain places were wiped out. If you're a nomad and you haven't got herds, you're like a taxi man without a taxi. You can't exist. So they had to leave, and a lot of young people went. And it was these young men who started writing poetry, as it had always been written, but about their situation, the misery, the exile.

There’s this word assouf. Assouf is the most important word in Tuareg poetry. Assouf is the pain that is not physical, the pain in the heart. It's nostalgia. It’s loss. It's grief. It's the coldness of a camp that used to be inhabited but there's no one there anymore. If you look at the lyrics of Tinariwen with the lyrics of Tamikrest, assouf is there everywhere.

So basically, it was a matter of putting two and two together. That's what Tinariwen did, the founders of Tinariwen: Ibrahim ‘Abaraybone,' Hassan, Kedu, Japonais, Jiarra. These are all the originals, and they did that in ‘79. Ibrahim got his first real guitar in '79. He was 18 years old, and he bought it off an Arab guy in Tamanrasset. I can just imagine like 10 of them sitting around this one guitar.

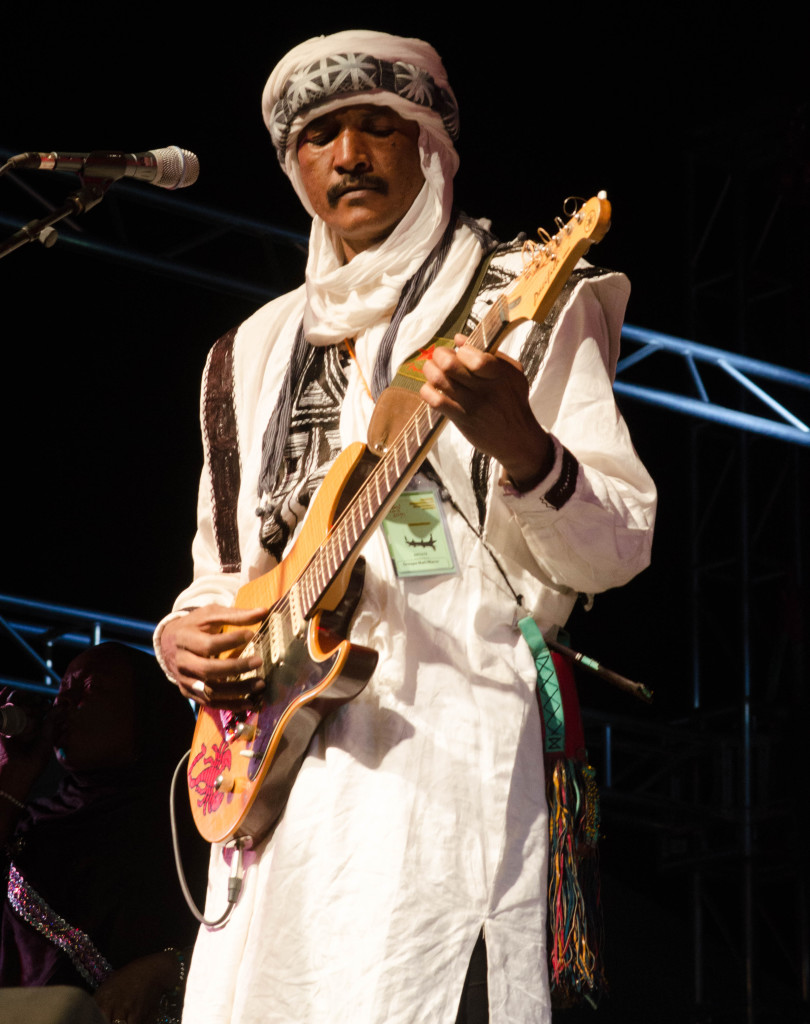

Ibrahim Ag Alhabib, New York (Eyre 2011)

Ibrahim Ag Alhabib, New York (Eyre 2011)

That's excellent history. You know, I spoke with Susan Rasmussen, the anthropologist of Tuareg culture. I asked her what was the difference between ishumar and traditional Tuareg music. She said that the guitar was important because it transcended a lot of other roles and restrictions that governed other music. Would you agree?

Completely. It's a very, very good point. Because the music was always proscribed, as it is in the rest of Mali. In traditional society, you couldn't just start playing music. You couldn't just be a musician. In the southern Tuareg societies, you have the closest contact to Bambara, so you have a kind of griot-like figure. Those are the ones that play the tehardent. But again, it's all tied up with the whole artisan cast system Tuareg society. And in the north, where there is less of that contact with the farming and fishing people on the River Niger, music was, until recently, a women's activity really. Tinde drum, imzad. The men would recite poetry and play the shepherds flute, and that's about it.

And so in traditional society, every instrument came with this social baggage. You had to be this, you had to be that, you had play this repertoire, you know. The guitar was the unburdened instrument. It was free. It's not Tuareg at all. It comes from somewhere else. You could just pick it up and sing. That was hugely liberating.

Susan is absolutely right as well that the whole Ishumar rebellion was both an external and internal—a revolt against oppressors of all kind in Mali, but also against an outmoded hierarchical clannishness, the idea that, “We, the Tuareg, need to get rid of our clan mentality.” They were young, and it was the 1970s. It was the spirit that was happening in lots of parts of Africa. Just this idea that we need a better future, less dominated by tradition and hierarchy.

What about the music itself? What is “traditional” in Ishumar music?

I think the rhythms are often based on tinde rhythms. The tinde drum is the heartbeat of Tuareg music. And the melodies? To be honest, I don't really know where the melodies come from. I know that Tinariwen’s songs were written in a very modern way, the way bands write music. Someone would come along with an idea, maybe a melody, a chorus; they'd sing it, and everybody would join in. Then someone else would start writing lyrics. They weren't playing folk songs. They were writing their own. That's what makes them revolutionary in a way, that they were definitely playing their own music.

Tumast culture center in Bamako (Eyre 2016)

Tumast culture center in Bamako (Eyre 2016)

Let's talk about lyrics. Mohamed Ag Osade of the Tumast Tuareg culture center in Bamako gave us an interesting chronology of these bands and what was different about each one. Tinariwen are of course the well from which everything springs. He kept using this French word revandications to describe their early songs. Literally, revandications are “demands.” But did their songs actually make demands?

When you look at the lyrics of Tinariwen, it's not what I would call revandications. But it's political. It's about awareness. So many of Tinariwen’s songs begin “Imidiwanin.” “My friends.” They are talking to their circle. They're talking to people like them. "My friends, wake up, be aware. What's happening to you? Someone who doesn't know his past…" I'm making this up because I don't know Tinariwen lyrics off by heart. "We’re erring in the desert. We’re thirsty. What is our future? Where are we going?" Sometimes they got quite martial. There were rallying cries. Some of Hassan’s songs that date from the 1980s are kind of, “We are fearless. We don't fear death. We will be like eagles flying over the mountains."

Mohamed Ag Osade (Eyre 2016)

And there’s a very interesting gender element as well, where the women expect their men to do certain things, to be brave, but also to protect the homeland, to protect their families. “That’s your responsibility as a Tuareg man. Abdallah Alhousseyni’s has this famous song, “Chet Boghassa,” “The Girls of Boghassa.” Boghassa is a village north of Kidal. And in the rebellion of 1991, there was a rebel attack on the military post there. It was repelled initially, and Abdallah wrote this song saying, "We have got to do it again, because the girls of Boghassa expect it of us." This is our duty to our women, to protect them, to fight.

So when Mohammed says revandicateur, he is saying “political,” with a small P. That's what I think he means. But in the Tinariwen canon you get much more personal songs as well. Ibrahim writes very personal songs. “Assouf ag Assouf,” “Assouf son of Assouf.” He lost his father in the 1963 rebellion, and almost as bad is that the Malian army destroyed the family herds. Because his father was suspected as a rebel; he was probably a rebel. And they were informed by someone that the herds of Alhabib, his father's name, were in a certain pasture. So they literally turned up with a couple of pickup trucks and just got the machine guns out and destroyed them, shot all these animals.

He was very young.

He was a child, 4 years old or something. But he remembers it. And then he had to escape into Algeria, and so many of his songs are about loss. Assouf.

There is a song called “Azawad” on the live album, the newest one. Do you know anything about that?

I'm not sure. What's interesting now is that Eyadou, the bassist, is beginning to write songs. He's the younger generation. He's beginning to write songs about the present conflict, whereas the older guys aren't really. Ibrahim is not really writing anything. Ibrahim is kind of semiretired.

And what of these new song saying?

“Toumast Tincha” is the big one. "A people united will never be divided.” It's all about unity. Unity is a massive topic in Tuareg music, especially after ‘92, when the rebel movement degenerated into all this bickering and infighting between different Tuareg factions. That was a huge psychological shock to people, that this should happen. Because before then, it was quite united. Abdallah wrote a lot of songs about that.

So the bass player, Eyadu ag Leche, and others in the current band, when they are writing about unity and social cohesion, is it unity for Mali? Or unity among the Tuareg?

I think mostly among the Tuareg. It's the same issue. We need to stop bickering with each other. We need to stop the clannishness, and stop letting other people divide us. Tamikrest is a lot on that issue. Tamikrest released an album called Chatma, which is about women: “The girls. The sisters.” It’s about the way women take the brunt of rebellion, because they have to attend iron fires during war, and that's really difficult to do.

Tell me the story of Tamikrest.

Tamikrest is led by Ousmane ag Mossa. He's sort of the second generation. He grew up in Tinzawiten, which is a little village up near the Algerian border. There was a French woman called Odile Hardy and the Tuareg man called Hama Ag Sid’Ahmed. They started the school in Tinzawiten, funded by donations in Europe. It educated lot of people, and it had quite a lot of music. And at one point, out of the school's musical activities, emerged this band Tamikrest, which means something like "the knot." The thing that ties us together, the binding. Before the conflict, they were hanging out in Kidal a lot, and to be honest, becoming the group that the youth of Kidal were really interested in, more than Tinariwen.

Tinariwen are the old. You know, it's like 1990s people. They like Bob Dylan and the Rolling Stones, but it's not their generation. They still pay them immense respect. I went to a dance in Kidal where Tamikrest was playing, and people absolutely loved it. Then when the conflict broke out, they kind of relocated to Tamanrasset.

How about Amanar?

Amanar is Ahmed ag Kaedi. He's based in Bamako. Amanar is also a band that had a lot of supporters in Kidal, but he has always been a pro-Malian, prorepublic. He doesn't like the idea of Azawad or separatism, and I think that also made him a certain number of enemies in Kidal—enemies in the Malian sense. And that's what we have so much trouble understanding. The Malian definition of enemies is different. "He's my enemy," but then suddenly you're taking tea with him and getting on like a house on fire. And the next day, you're his enemy again.

Ahmed had a terrible experience when he left Kidal for Niamey and Ansar ud-Dine took over—Ansar ud-Dine being the Islamist militia led by Iyad ag Ghali. Ahmed phoned up and his sister told him that the Islamic police had come around to his house and asked if he was there, and she said no, and they said, something like, "Well, tell him that if he comes back, were going to chop his fingers off, the ones he plays guitar with." It might not been as dramatic is that. But basically "We don't want him here." And they burned all of his musical instruments and gear. So he's in the south now. He lives in a part of Bamako that is like a Tuareg suburb, as I understand it.

Ahmed Ag Kaedi, Amanar, at Festival Sur le Niger, Segou (Eyre 2016)

Ahmed Ag Kaedi, Amanar, at Festival Sur le Niger, Segou (Eyre 2016)

Interesting. Well, that makes sense, and explains why Amanar would be in the Caravan for Peace concerts.

Yeah. Yeah. But again, he shares a lot with the ideals of the rebellion—political autonomy and development. I mean nobody says we don't want the north to develop. But what he doesn't like is the kind of machinations that go on at the head of the rebel movement, the very human politics. He thinks there are quite a few hypocrites involved.

What about this idea of separation? How much popular support did it have? Disco of Tartit said lack of education and opportunity led many regular citizens to back the idea. She estimated that at the inception of the 2012 rebellion, something like half of all Tuareg supported the idea of separation.

Who knows? Because no kind of public opinion polls were ever taken. But certainly I would say that in the Kidal region, you would have a majority of people who were into the idea of a separate nation. But you know, the Tuareg are spread everywhere from Menaka to Timbuktu, and all points in between. And each Tuareg faction has a different opinion, and people within the faction have a different opinion. The thing is, all the rebellions, since 1963, have been not only led by Tuareg, but by Kidal Tuareg, and not only Kidal Tuareg, but this family called Ifoghas. The rebellion of 1963 was led by one of the two sons of the Ifoghas chief, a guy called Zeid. And it's his brother Intallah, who then became the kind of hereditary chief. Intallah was pro-Mali, and his brother was anti-Mali, which is a fine imitation of how it's very, very difficult to kind of decide who's pro and who's against.

Fadimata (Disco) with kids at home in Bamako. (Eyre 2016)

Fadimata (Disco) with kids at home in Bamako. (Eyre 2016)

So how do these ideas get expressed in song lyrics?

The songs that I've heard have more to do with abstract themes of unity. You won't have a song finely analyzing the pros and cons of independence. That's just not the way the songs work. They're not political in that sense. It's more to do with, "If we stand united, we can achieve our goals." And the suffering, because ordinary Tuareg suffered a great deal. That's what comes out in the music.

Khaira Arby told us that she would go back to Timbuktu in a minute. She acknowledged security issues, but said she could be playing for five nights a week around the region. The audience is there. People are ready to go out and play music. The problem is equipment. She talked about a PA system that Ali Farka Toure had bought for her, with guitar amps, speakers, mixing board, everything. Apparently it was destroyed during the occupation. But she said if she had something like that now, she could return to Timbuktu and resume her career. What do you think?

I think the reason Khaira doesn't go back is because there's no tourism. What is the scope of a musician’s career in Timbuktu at the moment? It's very limited. You're going to play a few weddings for people who are rich enough to afford you, which is not many, and you are going to play some of these big showcase gigs for peace or reconciliation. There have been two or three since the end of the occupation. But the insecurity there is also an issue, and it's not related to any ideology. It's just banditry. There are a lot of small weapons now.

I saw that there were fewer Tuareg people on the street in Bamako on this recent visit. I heard stories about how they were mistreated after the rebellion—Tuareg houses burned, businesses destroyed… They say that now it's better, but there's still some lingering tension. How bad did that get?

It got bad at one point, but not for long period of time. My barometer on all that is Manny Ansar, the founder of the Festival in the Desert, because he's a Bamako man. He's lived in Bamako most of his life. There was one point in 2012 where he had to leave and go to Ouagadougou, but I think it was only for three or four months.

Manny Ansar at Segou peace forum (Eyre 2016)

Manny Ansar at Segou peace forum (Eyre 2016)

Manny mentioned that during a panel discussion around the Caravan for Peace in Segou. He said his daughter made him go back to Bamako. That was home.

Famously, in Kati, which is the little garrison where the coup d’etat happened, there was a Tuareg family who ran a very well-known and well-respected pharmacy. That was looted and pillaged, and they had to go. So there were cases. But it wasn't the pogrom could've been.

I mean, look at Mohamed Ag Osade and the Toumast center. He's the guy. His life's mission is to keep the flag flying in Bamako for Tuareg culture. The guys in Songhoy Blues tell me that there are quite a lot of young Tuareg now back in Bamako. When Songhoy Blues plays, they're playing to the northern community, Songhai and Tuareg and Fulani from the north. So they see these kids, teenagers, students, coming to the gigs. And apparently there are quite a few of them.

We saw a Tuareg group called Amal Ohar playing at Toumast. But there were very few people there, and they left feeling rather dejected. And Disco of Tartit says her band doesn't get invited to very many events. She doesn't feel included in the musical life of Bamako. Still, Mohammed said that even in the worst of the crisis, he, and Toumast, had never had any instances, any hostility at all.

Yeah, which is indicative. You would've thought that they would have been completely targeted. I mean, I think there's always been a mutual kind of racism. Let's face it. The Bambara call the Tuareg the peau rouge, the redskins, and quite a derogatory way. Some Tuareg are racist towards black people. I think we have to accept that.

What about Gao and Kidal? We couldn’t visit those places, but I’m curious to know what you hear from up there.

Basically, during the occupation, northern Mali was divided into three zones. You had the Gao zone, the Kidal zone and the Timbuktu zone. And each one was more or less run by a different Islamic jihadist faction. And the ones who ran the Kidal zone was Ansar ud-Dine, the militia of Iyad ag Ghali, who was a key figure in the modern history of the Tuareg—kind of the Che Guevara of the Tuareg.

But he found religion in the 1990s and became convinced that the future of the Tuareg was best assured by adopting rigorous jihadist Islam. So he took over Kidal and music was banned. What protected musicians in the Kidal region was that you could always go off into the bush and play whatever you liked, because there was just no one around. In the towns and villages, there was an Ansar ud-Dine presence and it was difficult to play music. Although there are multiple stories of hypocrisy on the part of the Islamists. You could have a bunch of Islamists who would spend a day going around punishing people who play music; then in the evening, they would secretly go away and have a little jam session with some of their friends.

So then the French came, and the occupation ended, but it seems to have left a psychological effect. It has dented people's capacity to enjoy the music in the carefree way they used to in the traditional setting. The period of the year when music-making is most intense is after the rains. You get the rains in June, July, August, September, and then it's just a huge relief for nature and for people. They play music to express their joy that everything's O.K. It's time to party. But last season I heard that this has been muted. People are less willing to express themselves and just go play with gay abandon the way they used to do. There has been an effect, unfortunately, of this kind of Islamist philosophy in people's minds.

Wow, that’s troubling. In Bamako, we sensed that the whole discourse around religion is changing. We heard about these two religious leaders: Ousmane Madani Haïdara and Mahmoud Dicko. What can you tell us about them?

Haïdara is hugely popular. He runs an organization called Ansar ud-Dine also, which is very confusing. It means “followers of the faith” in Arabic. Haïdara’s Ansar ud-Dine has lots and lots of adherents in the south of Mali. But he is the classic cult personality. He is Sufi. I think Tijaniyya is the brotherhood he belongs to. He receives an awful lot of donations and has become immensely rich on the back of it. The words he speaks are inspiring for a lot of people, and quite spiritual, but he has this thing about being a wealthy man, and that goes against the whole point of the Wahhabist, Salafist philosophy, the philosophy of Mahmoud Dicko.

Wahhabism is alien in Mali. It was born in the Middle East, but it started coming into Mali a long time ago, a lot earlier than we think, in the ‘40s and ‘50s. The way Manny Ansar always explained it to me, which I thought was quite revealing, is that they were perceived as a kind of religious cult when he was young, the way we might see Jehovah's Witnesses or the Moonies. You didn't want your kids to get involved. They could be sort of led off and disappear.

But the thing about the Wahhabists is that they are seen by a certain fringe, a young, often well-educated fringe of the population, as being the revolutionary option. Because their whole philosophy is that you don't build any living person into a kind of cult or position of preeminence. That is sinful. So people like Haïdara are an absolutely a clear example of what a Muslim should not be. The true imam in their conception should be a humble, strict, rigorous, self-effacing person, very instructed in the scriptures. Everything relates to the reading and the understanding of the scriptures. So all the Sufi activity we know and love, like music, is completely sinful.

Tuareg group performing in Bamako (Eyre 2016)

Tuareg group performing in Bamako (Eyre 2016)

But that's not in the scriptures. The Koran doesn't ban music.

I know. I know. But the Salafists, the Wahhabists, feel that it's an addition. Even if it’s not explicitly forbidden, it's what they call bidan. It’s not included, not an original directive. And this explains a lot what happened in Timbuktu. It is sinful to erect a mausoleum or a monument to someone who was a living person. They're in a way very democratic. The Wahhabists say that everyone is equal, and then there is God. There is nothing in between. And Mahmoud Dicko, who is the head of the High Islamic Council, is the closest to an officially recognized Salafist figure in Malian society, and he is hugely powerful.

Gregory Mann said that a key difference between Haïdara and Dicko involves language. Haïdara believes you can worship in your own tongue, like Bambara. Dicko insists you must do it Arabic.

Yes. That's very much the Salafist/Wahhabist thing. The Sufis will say—and I completely agree with them—that the only reason Islam expanded in such an incredibly explosive way after the death of the Prophet is because it had a flexibility. It could incorporate local language, local traditions, which became elements of Sufi expression in various times and places. That's why within 200 years you had a mosque in China and a mosque in Spain. But the Wahhabists and the Salafists are rigorous: everything is Arabic.

I spoke with Toumani Diabate about this. He complained about how people from Bamako go off to the Middle East somewhere and spend a couple of years studying Arabic. But when they come back, they feel like they're better than everybody else.

Yes. That's true. Definitely. Because the Wahhabists feel that the Islam of Mali, the traditionally Sufi Islam, the brotherhoods, the Tijaniyya, is an Islam that is encrusted with barnacles. It's like a ship's hull that's been at sea too long. It's been compromised by local language, local hierarchies, local culture. You've got personality cults, and people who are nominally Muslims but wearing pagan amulets around their necks. There is a really great contemporary Malian writer who told me that in his opinion, Mali is fundamentally a pagan country. And that Islam and Christianity have always been a city thing. It's civilization. Cities.

That's interesting.

Just look at El Hadj Oumar Tal in the 1850s and 1860s. Just look at the jihads he fought against the Bambara Kingdom, Bambara being an animist kingdom.

Yes. "Those who resist."

And Songhoy Blues has written a song praising El Hadj Oumar Tal to the skies. “Sekou Oumarou” which is a lovely song. But I find it weird because I've just read Segu by Maryse Conde, which is such a fantastic book. It talks about that issue and that era so fantastically. I'm not a specialist in that area, but jihad is not new to Mali. We've got to forget this idea that it's all kind of hunky-dory and everybody's lovely to each other, which they are in some ways. But it's not an innocent place in that sense. Maryse Conde refers to what El Hadj Oumar Tal did to the Bambara. Some have called this a kind of genocide.

And of course it was the earlier fighting that established the Bambara kingdoms that caused a lot of people to be captured into slavery and brought to the coasts where they ended up in the Americas. This is one of the explanations for why there's this close connection between Malian music and American black folk music.

Yes. Now we’re talking about the previous fight, over the lingering remnants of the Songhai Empire in the 18th century. This is the beginnings of the Bambara kingdom in Segou under Biton Coulibaly. The Bambara fought wars that they fought with various neighboring city states. You know, there is brilliant insight into that whole period in Mungo Park's Travels in Africa.

Yes, a truly great book, and I can also recommend reading T.C. Boyle’s novel that takes off on Park’s adventure, Water Music—an extremely funny book. Thank you so much, Andy. You’ve given us a lot to think about.

Thank you.