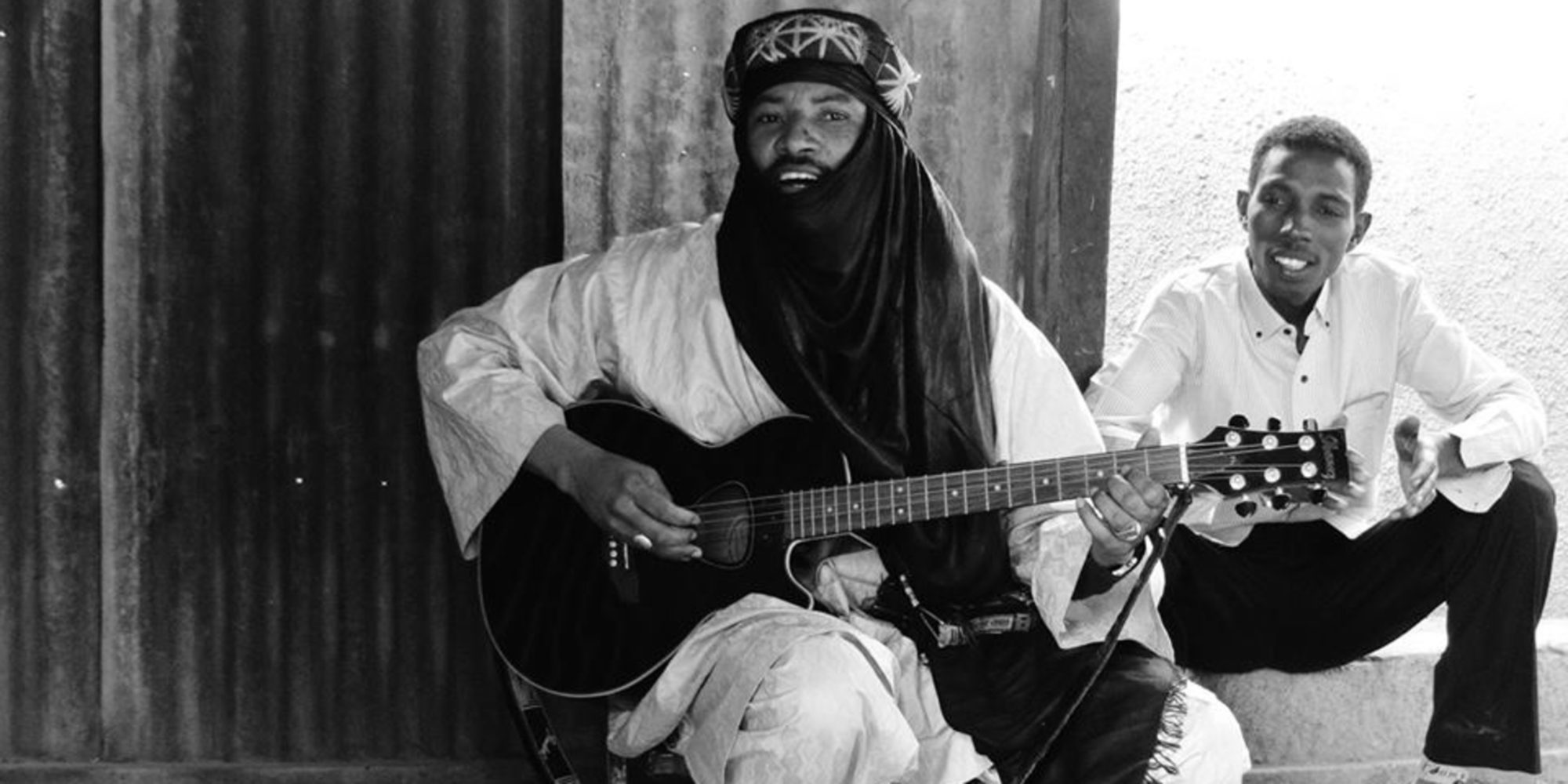

From Niamey, Niger, the respected Tamashek (Tuareg) guitarist Alhousseini Mohamed Anivolla is back with a second album from his solo project, named Anewal. The Berlin-based musician first came to our attention with his Nigerien Tamashek band Etran Finatawa. In May 2017, Anewal released Osas—It’s Time, recorded with producer/bass player Colin Bass. Afropop’s Banning Eyre writes that “bass guitar aside, Anivolla plays and sings everything here, creating the illusion of a finely tuned, highly disciplined combo. The result is elegant blends of acoustic and electric guitars, often three at once, hand percussion and Anivolla’s deep, grainy voice commanding center stage, mostly alone, with hypnotic, chant-like melodies.” Leading up to a Dec. 7 performance at Rockwood Music Hall in New York, presented by World Music Institute, Afropop’s Sebastian Bouknight spoke over the phone with Alhousseini Anivolla in Berlin. Anivolla’s manager, Sandra van Edig, translated from French and joined the conversation. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Sebastian Bouknight: Hello Alhousseini! So do you live in Berlin now or are you living in Niamey? Do you go back and forth between the two?

Anewal (Alhousseini Mohamed Anivolla): I’m living in Berlin but I’m leaving frequently as well to go to Niamey to see my family.

How long have you been in Berlin?

Almost five years now.

O.K., very cool. Do you miss Niger?

Niger is like a tree and I’m a fruit of this tree, so of course I’m missing Niger.

Mmm. Pretty much all the songs you sing about talk about the landscape and the people of Niger, so I imagine it might be hard to really connect if you’re living in a different place, you know? Is that a challenge?

[Niger] is a part of myself and I’m always in contact with that. Also I go there, I see the people and I’m in constant contact with people over there so it's not too difficult now.

As far as the music goes, who are you in contact with musically these days? Are there people in Berlin that you play with; who play your style of music?

First of all, the music has no borders, so you can also play this music here. But you have to be rooted in your music. You could play it with everyone or everywhere. There's some musicians here in Berlin that I’m playing with now. There's one percussionist I’m playing more with now, his name is Tunde, he's from Benin. And then I have musicians I’ve been playing with since I came here; there's Ismail and Jean. Jean is from Benin as well; Ismail is from Algeria. And I play as well with some musicians from Berlin—some local musicians. They all do projects here, so I’m joining them, playing some projects as well, or just rehearsing. So there's a big musician community here in Berlin, so I’m part of this community as well.

That's beautiful. How does it end up sounding when everybody comes together to play, coming from different musical backgrounds?

It's multicolored and it's very rich. It's like sand in the desert. It's like bringing all the different sounds like daylight and night all together, so it’s multifaceted.

That's beautiful. Besides music, do you find things that connect your two homes? Are there social or political situations in both Berlin and Niamey that are somehow linked to each other? Is there dialogue beyond music as well?

There’s some things I’m doing here [that are different]; playing in movies and movie productions here in Germany—little roles. It's not really the same like being here and doing these kinds of productions. Then, when I’m there, I just like to be there, to be my other half, walking in nature and feeling like my ancestors.

But sometimes things are coming together as well. Last year I was doing a film, a production here, and actually I was hired by a movie company to organize filming in Niger. So I brought all these cinema people from Berlin to Niamey last year and they're filming one part in Niamey. I was happy because I could bring these different kinds of activities together and show Berlin's actors and cinema people my home country. And of course I was very proud to because I brought these people and many people in Niger were very happy because…there were many jobs for the filming and it was really exciting to everyone. This was a moment when I could bring these two [worlds] together, being here and being part of that [Nigerien] society as well.

Wow that's really amazing! What is the movie?

It was a film about migration. It was a film about a young man from Mali who came here; he took the boat, he came to Italy and then he came to Germany, to Berlin.

Sandra van Edig: We had many, many migrants in Berlin last year and it was pretty difficult. So the whole movie was about this young boy being here in Berlin and then there was this flashback showing his life in Africa; the reason why he left and so on. So [for] the part in Africa, [they shot] in Niger.

Wow. That must really hit close to home as well. Al-Housseini, you didn't have to go the really difficult route to Berlin, but I’d guess you know other people that have left home for Europe—is that true?

So for me, I’m a walking man. [Anewal means “walking man”] For me, the planet is open for walking wherever you want. So migration is a central theme of my life [ever] since I was born. I know some other migrants—some people from Niger as well—who came here and did this migration through Libya and so on. It’s very interesting for me because this is not the way I feel life; I never question the idea of migrating wherever you want. I never felt any borders. I had the chance to move around with my family in Niger, in Mali...no borders. Go wherever you want. And later on, I’ve had the chance as a musician to go and travel. So I was never stopped somewhere that I wanted to go. I [have] had many chances.

It's interesting now for me to see [and] to meet with these young men—most of them are men—who are here and have all these borders to cross and all these difficulties and obstacles. And now they're here and they're suffering and they're homesick. It's very inspiring and it's a central topic for me. This film was also very important for me to be part of it. It's so interesting to see the different layers of migration.

Wow, powerful. What was the name of that film?

Sandra: It's a German film, it's called Der Andere, which means The Other. It was for…public television. I don't know if you're familiar with German television.

Not much. [Laughs]

Sandra: It was an evening movie. The name of the director is Feo Aladag. She had some prizes for other films and she's always very close with the people. She did a film about a woman in Afghanistan, so she does these portraits of people.

Cool, very cool! When many young men are leaving for life in a different place, how does that change the community back home? What do you think the future is? What are ways of keeping the community alive?

First of all, [there are] two different types of men—women as well—who will leave home. So there's those who go and will never come back and never leave a sign. And there's those who go and they search for a better way, a better life. [When] they don't find it, they go home and they don't feel any mistake. It's just kind of a discovery for them and they bring something back as well. Even if the time in the other country was not so successful, they will bring their own experiences back. So there are these two different kinds of men...

When man comes to Earth, he's just having his life, nothing else. So some of them will become ministers, some doctors, some will stay poor forever. This is what life is about. For the communities, they react very differently. Some [are] actually pushing their young men to leave because they want an outcome for themselves. [For them] it’s difficult to understand that once these young men are gone, they don't bring back anything or they just disappear. So this is very disappointing for these communities. For others they just say, “O.K., these young men…search for their way to live” and they can accept [it]. It’s difficult to answer this question because the communities are so different as well. Like in Nigeria or Niger or on the west coast [of West Africa]…there’s some communities [that] give money; they save money for the men to leave and push them to go. [There’s] other communities don't want their young men to leave. They say, “No, stay here and be part of our community.” So this is very different.

Actually, not so many young men from Niger are leaving. Most of the migrants coming here to Europe…are from the coastal areas [like] Senegal. But it's a very little community from Niger actually.

Ah, really? Interesting.

[It’s] very, very small.

How do you deal with these social changes in your music? In Afropop’s review of your recent album, Osas—It’s Time, Banning Eyre writes that there's lyrical commentary about how people have lost their identity or their culture and need to unify. So, what are you seeing change and how are you addressing it in your music?

So my music is out there to say to the young people, “It's you—it's up to you to know who you are.” I’m addressing the young people especially to find out, to be open, to be tolerant and to find out how to react. These days, it's not that everything is there and you just do as your ancestors have done. So I'm asking the young people to be open, to discover how things are changing and to take the time to understand it; analyze it and to find the best way to react…to fit into this transitioning system and survive. I ask for open-mindedness; being open to the changes as well.

It’s also very important to say, “Accept yourself, accept who you are...and don't try to be like somebody else.” If you don't know who you are, you're already lost right from the beginning. So this first thing [to do] is to be who you are. And then you're open to walk around and discover and to make up your mind about the changes [in the world]. But if you're not even standing on your own feet, you will never understand the other.

So who do people think they are? Who are people trying to be? The young people in particular, if that's who you're talking to.

Now the young people…dream they want to be presidents [and] ministers. They want to be celebrities, they want to be French, they want to be...somebody else. The worst is that the young people from my own community—from the Tamashek community—don't even speak their language anymore. This is really very hard to see. They refuse or they speak other languages; and they don't even know how to communicate in Tamashek. They're trying to be like other ethnic groups or American or French. It's just very difficult. I say, “You will never be French or American, you will always be Tamashek.

Right, wow. That's really a frightening thing to see, I'm sure.

You can learn many languages, you can [wear the] clothes of many people and accept all of these different and interesting ways of life. But you should never lose your own life and your own language. I’m not against this kind of getting inspired [by others] and being very multifaceted—because I am like this—but your inner light is your identity.

Right. That’s beautiful. What gives you hope for the community? What gives you hope for Niger and for the youth in particular? Is there something that keeps you hopeful?

I am hopeful, because the people from Niger…do not leave the country as much as other groups do. That gives me some hope. We’re going through a difficult time—we’re trying to...define who we are, or redefine. There’s a kind of a review process we’re in. There's something going on, so at least if [people] start to be conscious about the [danger of losing identity], I have hope that we might develop some kind of ways...to stay who we are.

That's good that you see something there! So, there seems to be a lot more Tamashek musicians from Mali and Niger who are going into music in the way that Al-Housseini is. You know, in the vein of Etran Finatawa or Tinariwen, Tamikrest or Terakaft. I feel like they are holding on to the Tamashek identity and using the language as well. How do you make your voice heard in that rich world of Tamashek blues and rock? What is your kind of signature?

What’s very important to me…is the acoustic approach. That's different because most of the other Tamashek bands go more for the electric sound. They go more for electric guitars and so on. I take an acoustic approach…the acoustic guitar is very important because [for me] the basis of the Tamashek music is really this; this natural approach, [the] hand clapping, [the] very soft sound of the acoustic instruments. [I also use] traditional instruments, weaving them into the new arrangements with a guitar. I use this musical bow, for example, [the tekedebena]. This is what the other bands are not using at all or not [focusing on]. This is something I’d like to underline in my music: the acoustic guitar, percussion and traditional instruments.

I remember reading that you also played almost all the instruments on the record?

Yes, this is right. This CD is really me. I’m proud of it—you can really feel my presence in this record.

Definitely, it's a beautiful album.

Thank you!

The name of the album is Osas—It's Time. Does osas mean “it's time”?

It means “it’s time” like “the moment has come.” Actually, it's like an abbreviation, because if I were to use this [idea], “the time has come to think about the world and to see where we are” in Tamashek, it’s a little too long…to use as a title. So I picked just the word “osas.” [The] songs on the album…are actually about this: “Look where we are, what has happened? It's really time to do something.”

Sandra: [In] the Tamashek language…you can pronounce [words] in different ways and [they will] mean different things. So you can say something [one way] and it will mean “It's all well wrapped up,” and then you can say it [another way] like, “O.K., all is wrapped up now, so let's go.” So it's a very symbolic language, with many metaphors behind one word. So for Tamashek-speaking people, osas leaves it open in many directions to understand what it means. But for [those of] us not fluent in Tamashek, we take it just as “the time has come” or “the moment has come.”

Beautiful, I like that a lot. I saw that the album is dedicated to Altine Anewal Muhammad—who is that?

It’s my father. It's in memory of my father and my grandfathers. I keep the name of my grandfathers as well. Altine is my father and Muhammad and Anewal are my grandfathers.

Ah, beautiful. So Anewal is the name that you’re using for this solo project and it’s also your grandfather’s name?

That's it. It's also the image behind it because my grandfather has taught me many things and has brought me all over. For me, my grandfather is the man who was walking around, so the name is my mission [in a way]. The name Anewal…in Tamashek, when you translate it into English, means “walking man.” [This name] shows how anchored I am in this culture and how much I appreciate the ancestors and the traditions…in my personal life as well. This is all behind [the name] Anewal.

That's really beautiful. It's clear how much you practice what you preach. Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me, I really appreciate it. Merci, Alhousseini.

Merci beaucoup. Take care and have a nice day!