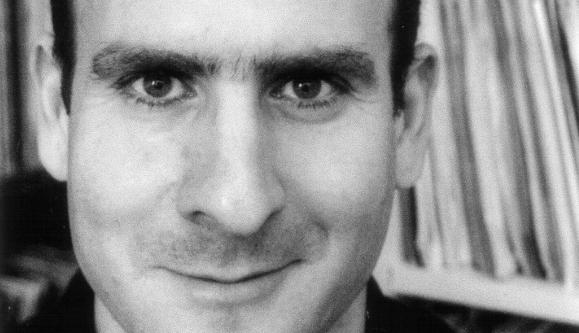

One of the world's foremost authorities on reggae, dub, and dancehall, David Katz has written several books on a variety of Jamaica's musics, including People Funny Boy: The Genius of Lee Scratch Perry and Solid Foundation: an Oral History of Reggae. As part of the research for Afropop's program "Jamaica in New York," producer Saxon Baird chatted with Katz to talk about the history of New York's reggae scene.

Can you begin by talking about how the New York reggae scene was established?

Well, the first seed of New York's thriving reggae and dancehall scene goes back to the pioneering sound system operator and record producer, Lloyd "Bullwackie" Barnes. It's crucial to the whole development of the reggae scene in New York.

Bullwackie (Lloyd Barnes), a Jamaican who grew up on the rough streets of Trench Town, the same neighborhood that Bob Marley and the Wailers sprung up from and countless other harmony groups. He was one of those downtown bad boy types hanging out on the street. In fact, the way he gets this name "Bullwackie" is because he used to run with this gang called "The Bullwackies." He was one of these links man as in everyone knew him. I think he might have been close with Studio One founder Clement "Coxsone" Dodd, as well as Alton Ellis, Peter Tosh, and members of the Skatalites. Before Bullwackie migrated to New York, he recorded a couple of tracks in the ska years. So he did a song for Prince Buster but it didn't really get anywhere. And eventually, like a lot of people of his generation he went up to New York in search of a better life.

So Bullwackie gets to New York and ends up establishing New York's very first reggae sound system. Which naturally was called "Wackies." So Bullwackie is really an integral force in this whole development of that scene. And he doesn't only limit himself to having a sound system. Setting up a recording studio was a natural next step.

The other thing I would mention about the whole reggae and dancehall scene in New York is that because there was such a strong Jamaican presence in the city, it seemed almost inevitable that a kind of strong reggae and dancehall scene would develop there. So you had a lot of other singers who would also become important forces in Jamaican music production who spent significant periods in New York. I'm thinking specifically people like Linval Thompson. Who again, migrated up to New York to join his mother. Thompson made his first recordings in New York then subsequently went back to Jamaica where he broke through in recording for producer Bunny Lee before becoming a producer in his own right.

So a lot of people and a lot of important musical figures have this New York connection. You also have Glen Adams, the keyboardist for The Upsetters and the Wailers, who migrated up to New York and set up a record label there before starting to license and release music that was recorded in Jamaica for release in New York and also began to produce his own music. Glen ended up bridging links with the New York hip-hop scene which also has a lot overlap with the Jamaican dancehall scene as I am sure you know.

Going back to Bullwackie, as things sort of started to evolve slowly from the mid 70s coming up. You have a lot of important artists establish sort of residencies at Bullwackie’s studio, based in the Bronx—he’s had more than one recording studio in more than one premise, but the "flagship store" up on White Plains Road is where a lot of people like Sugar Minott ended up making significant, very innovative music there. For example, Minott cut an album called Dancehall Style, which was a "showcase" LP where every song was immediately followed by a dub version. You also had Leroy Sibbles from The Heptones becoming a mainstay at Bullwackie’s. Members of the band Chalice were there and so on. So I would say Bullwackie was a really integral force.

You had some other studios and related outfits like "Munchie" Jackson who was a partner of Bullwackie. And then you have all the sound systems that get more prominent into the 80s. And you have the one that becomes dominant which is King Addies. Where the selector Tony Matterhorn came up from Jamaica and helped that sound to become the leading sound system of the day. You had people like Brigadier Jerry who had long periods of residencies in New York. Ranking Joe ends up eventually settling in New York.

I suppose you could say that it's part of what Paul Gilroy talked about with the concept of the "Black Atlantic." You have New York in the middle of that with this exchange of cultural practices and information going back and forth between Jamaica, London and New York. So New York is kind of a crucial spot in that regard.

Since you mentioned Bullwackies, let's talk about him. It's interesting because despite being a real integral part of the New York reggae scene, he was never really able to produce any hits that were popular in Jamaica.

I think he wasn't aiming his music at Jamaica. That wasn't why he was making his music. And Bullwackie and his peers in their early days had two methods of making music. If your familiar with a Little Roy compilation that came on the Precious Sounds compilation or another one called Tafari Earth Uprising the Tafari label owned by Munchie Jackson and his brother. And basically what they did was take cuts of old Jamaican riddims from producers like Lee "Scratch" Perry, they weren't his contemporary productions, but these old cast-offs from six or seven years ago. And they took these to New York and voiced them with the people that were around their sound. DJs like a guy called Jah Vill, and they had a sax player called Baba Leslie who was active in a band called Tribesman, and he blew new melodies over this old riddim called "Tight Spot" from '69-'70. But these guys were doing it around '74. And then, once Bullwackie had enough studio space to record on your own, you didn't need backing tracks. So they started making their own music.

And obviously, if you think about Jamaica, it's very insular. Whereas New York, there is a lot of different cultural information that is all around. So it makes sense that what Wackie was creating wouldn't necessarily make sense to Jamaicans in Jamaica.

I think it’s similar to the music that was being made in the UK if you think about Jah Shaka and his productions. Again, Shaka being a Jamaican that migrated London and established his sound system there. By the time he starts to record his own productions, they sound like nothing that was popular in Jamaica. I don't think they had Jamaica in mind when they were making their productions, really. So I would say that’s the same with Bullwackie.

What made Bullwackie’s sound so unique?

One main point of reference for Bullwackie when he started to make his first productions, was that he was clearly influenced by the productions of Lee "Scratch" Perry. Particularly that era at the Black Ark. Perry opens the Black Ark at the end of '73 and it has a sort of peak and a pinnacle in '78. And then the doors are sort of shut in '79. But what Lee "Scratch" Perry did at the Black Ark, that music wasn't popular in Jamaica either. So if Bullwackie was trying to emulate a little bit of the Black Ark then maybe that's a starting point.

For Bullwackie though, I would say that it was very lo-fidelity. And part of that was because the equipment was technically limited. And then there's something about his arrangements and his productions, spatially they may be a bit sparser that was happening in Jamaica at the time. You know, Bullwackie was renown for his dubs and those dubs are pretty densely textured and heavy on effects. And in terms of the singing and DJ tracks, I think of the kind of vocals he was producing…if you think about the track by Aminatu, "Runaway Dread," these are very minimal productions values with maybe technically limited artists, if you see what I mean. But that's also part of the appeal. Its rough and ready, low-budget, lo-fi music for a rough and ready environment. The Bronx in those days was very rough.

It sounds like Bullwackie was coming from a place of real artistic integrity. Sounds like he didn't seem very interested in appealing to a certain market or crossing-over then.

Sure, I agree with that statement. I think Bullwackie was very much of his community. And the sound system was very much of that community. And the way he described it, they weren't even really thinking about making music. It's just the way it evolved from the sound system. Because everyone gravitated towards the sound system. So naturally you have DJs and toasters constantly active on the sound, and singers as well. And so beginning to make music was a natural next step. But its not like Bullwackies said, "Oh, I am going to set up this sound system so that I can start making money as a record producer." Nothing like that. If anything it would have been the opposite.

But you know there was all kinds of talent in New York at the time. And you can think about singers like Wayne Jarrett who also came up through that link and recorded significant material for Wackies there. And other artists who may be wouldn't have recorded otherwise. Like the Lovejoys, these two female singers. And even The Chosen Brothers, of which Bullwackie was a part. But you know, when you hear it, it's like you say, it's instantly recognizable as New York. And instantly recognizable as Bullwackie for that matter.

Do you think New York-based reggae that was finding popularity in Jamaica, like some things that were coming off the Jah Life label, was trying to appeal to that audience?

I think Jah Life was more in tune with what was going on in Jamaica because he was going back and forth. And he was doing some of his productions in Jamaica. While Bullwackie was not doing that for whatever reason. So maybe that's partly why what Jah Life did was so much more successful in Jamaica. If you think about some of the early Barrington Levy, it's Jah Life going to Jamaica with riddims he had constructed in New York. The exact opposite of what Bullwackie and "Munchie" Jackson had done with Tafari, and some of those early Aries releases that were produced between Munchie, his brother Scorcher, and Bullwackie. So I think that's the reason why we get those Carlton Livingstons and some of the other productions he had. He wasn't only doing it in New York, and he wasn't only doing it for New York.

So when you think of a definitive New York reggae sound, Bullwackie’s seems to be the place to start?

In my view, yes. Instantly recognizable and very "New York" in feel if we can say such a thing. Now a little later you get people like Phillip Smart at HC&F. Again, instantly recognizable as a "New York" sound and maybe made with New York in mind. This is like a New York dancehall sound that he starts to develop at his studio in Long Island. And I think, once again that's partially because he wasn't traveling back forth from Jamaica so much. So maybe that's the key difference. Those that stayed outside of Jamaica had more artistic individuality that was noticeably New York.

During this time, there was a very intense and violent political social situation going on in Jamaica which seems to be part of the reason why a lot of Jamaicans were migrating. And on that note, can you also touch upon the role that drugs and gun smuggling had on the funding of these New York-based studios?

You've hit on some very important elements that are very true. Every time there was a change of government, specifically in that era, the whole musical environment changed. And that includes the whole musical environment where there were large Jamaican diasporic communities that also changed. Most notably, this is felt in London, New York and Miami. The key change where these seismic shifts take place is after the 1980 general election in Jamaica when Edward Seaga is elected. Not that long after that, the whole roots and culture thing fizzles out in Jamaica. Now look at a producer like Skengdon, who was based in Miami, and he ended up based in Miami rather than Jamaica because of the change of government. I think this is definitely true with those who were based in New York. Like Lee Van Cleef, or some of those other toasters who were up there in that era. Probably some of them ended up in New York because of how the government changed in Jamaica one way or another during those years.

And as you said, the other change that comes into it, is that you start to have strange studio projects being financed which may or may not have been money laundering or, the way it was expressed to me by some artists in Jamaica was that during the dancehall era, a little later in the 80s, you started to have some dancehall producers who had no real musical skill or knowledge, and who made their money through drugs, but channelled their drug money into recording projects. Inevitably, you ended up with some music being produced that maybe had less musical merit, if you will. I think all these things are part of it. Its a little bit difficult to disentangle fact from fiction or certainties from supposition, though.

The other thing I would say is that there is a sense as well, both in Jamaica and in New York, where in the 80s you start to feel the presence of cocaine in the music. In the 70s, maybe everything seemed a bit slowed down, psychedelically stoned music with maybe marijuana as a reference point. Once you come into the mid '80s, the music gets pared right down, and amped up, and it’s really a kind of a short attention span, cocaine-vibe in the music.

Moving away from New York for a second, I want to go back to something you touched on about how the government changes in Jamaica kind of coincided with the music changing. Paul Gilroy in his book "Aint No Black in the Union Jack" touched a bit upon this. His take is that part of the reason why the roots, reggae feel waned and the digital-era of dancehall came into popularity and themes of slackness and gun talk increased was because the Reagan-backed Edward Seaga administration came into power around this time. In other words, the music became more materialistic and "free-market" if you will, which of course, reflected the politics and policies of the time.

I think its pretty undeniable when you look at it. Although when I interviewed Edward Seaga and suggested this to him, he was pretty aghast at such a suggestion. On the other hand, Ray Hurford, who used to do Small Axe magazine and who still does some publications, said that Seaga made a statement about this, specifically about wanting no more social commentary in the music from here on. And funny enough, that's what happened to a large degree. It wasn't immediate, but it eventually came to be. Seaga takes office in '80, Bob Marley dies in '81, etc. But yeah, the music was kind of changing before that anyway.

That being said, I think the change of government was key because a lot of things happened from that shift both intentional and unintentional. You know, Michael Manley had been in power for 8 years. And in his first two years, he brought in this strange and ill-defined method of governance, or a system that he called "Democratic Socialism." And it was never really clear what "Democratic Socialism" was supposed to mean, whether it was actually just Socialism or Communism, but with a “Democratic” tag at the front so you wouldn't get too scared of it, or something.

Then the 1976 general election was really bloody, where there were hundreds of deaths from politically-motivated violence. It was very much like an undeclared civil war. Then Manley gets re-elected but by then the country is heading for bankruptcy. And the policies weren't working for the betterment of the people. Then you had an influx of guns and a rising of gun crime, so in 1974 he unveiled the Gun Court, where you would have indefinite detention if you were even found with one bullet. And this is from a guy who was supposed to be on this platform of human rights.

So going from a period on the Left, and being vocally on the Left and moving toward a collective consciousness and an a collective work ethic, and making these ties with Castro and so forth, to this Reagan-backed, free market with a capital "F," headed by Seaga, was definitely a drastic shift. And typically what tends to happen with diasporic communities, and in particular Jamaican ones, is that they have looked to Jamaica first to sort of emulate what is happening there. And, on top of that, there is always passage back and forth from those communities. So take a guy like Bullwackie who, even if he wasn't travelling back forth himself to Jamaica, the artists he was working with were, and his friends, associates, and whoever else.

Then musically, Jammy unveils "Sleng Teng" and it causes this seismic change in the music in Jamaica. But we shouldn't ignore also the influence of cocaine, which was definitely undeniable from my point of view of a listener, as well as an observer. And many artists I've interviewed have said to me that this was when the music business became like a drugs money thing. So they got these instant, overnight producers, who probably didn't have a lot of interest in music and didn't necessarily have a lot of skill.

How much of that filters into the New York scene? It's a little difficult for me to say, but I think the presence of cocaine, which really wreaked havoc in the Jamaican communities in New York, is undeniable. And so some aspect of that influenced the music as well.

In fact, you had a lot of entertainers who were based in New York who ended up dying these tragic deaths, and this spectre of cocaine is never far from them. If you think of Fathead and the whole Super Cat - Nitty Gritty tragedy, which supposedly stemmed from a disagreement over the proceeds of a dance that hadn't been shared equally, and disrespect and so on… And if you can picture that it happened in Count Shelly's record shop, another major focal point in the music—particularly in dancehall music. Although, Count Shelly, interesting enough, he's a Jamaican who migrated to Britain first, where he was one of the most prominent sound system operators, as well as a record label owner that released music that was mostly made in Jamaica. Then he leaves London and migrates to New York where he opens the largest Jamaican record store in New York, that's a total focal point and meeting point for Jamaicans. He was distributing a lot of products for guys like King Jammy and became instrumental in helping that whole digital dancehall trend to sweep over the Jamaican communities in New York. But even then, it's kind of telling that it would be there, where you have this terrible story of these two DJs/Sing-Jays who had been on the same sound systems together, who were not meant to be enemies, and one killing the other one. And so I think this was very symptomatic of that era. But its quite possible in my view that none of that would have happened if there hadn't been that change in government.

If you read the book "Ruthless: The Global Rise of the Yardies" by Geoff Small, he talks about the way the change of government meant that foot soldiers who had been involved in enforcing political loyalties in different neighborhoods in Kingston, and elsewhere in Jamaica, a lot of these guys gets spirited out of Jamaica, and they end up major players in the underground crack and cocaine trade. And naturally, there is a lot of violence involved with these guys. They were people that were initially armed and funded by the rival political parties in Jamaica. But later, the rivalry is more about control of the drugs trade.

Well this brings us up to a point where in New York you have this explosion of studios and labels in New York in the 80s. And then you have some cross-over hits made in New York but popular in Jamaica like Shelly Thunder's "Kuff." Then there’s the Flatbush crew with Red Fox, Screechy Dan and Shaggy coming to prominence with Shaggy, of course becoming a major international superstar.

In terms of Shaggy, he's very much a New York phenomenon. And I think that part of what helped Shaggy break in the U.S. is Philip Smart and the environment of his studio and the way he makes artist there feel so comfortable and relaxed in there. Also, Smart, of course, had his training in King Tubby's studio. You can't really get your training any better than that when it comes to reggae and dub. I think Philip was someone who was able to adapt to whatever changes were happening in Jamaican music very easily. Some people will say that with Wackies, that the transition to digital music didn't go so successfully, though, it should be mentioned those Wackies digital releases were popular in Japan. When you listen to the Wackies stuff of the mid to late 70s, it's just totally classic. When you listen to the Wackies of the mid to late 80s, it's not quite as "prime," if you will. Still interesting and still very New York, but not quite as distinctive and hard-hitting.

I think the other thing that happened with these major hits that you mentioned, is that we can't forget that Maxine Stowe, who was Sugar Minott's wife, was working for the majors then. She came up with Sugar when he started working with Wackies, then she worked at Island, and then started to work for Sony and the Chaos label which was a little dancehall subsidiary label. She was able to funnel artist their way that had that cross-over potential, and they did enjoy these crossover hits. On the other hand, with tragedies like the whole Super Cat - Nitty Gritty thing, I think the majors backed off a bit. And then I remember people like Lieutenant Stitchie, who was signed by Atlantic, but the label didn't really know what to do with him. It was always that classic thing where they watered the music down too much in order to try and make it crossover, but then it didn't really appeal to a wider audience, and it didn't appeal to its core audience either.

So you have these major American U.S. labels picking up dancehall artists and not knowing what to do with him, then dropping them. And then you have, supposedly, a lot of these shops and labels shutting down because the money begins to dry up or people are getting deported. And then, as I mentioned, by the 2000s, things sort of disappear. Why is that?

I think that there are a variety of things that come into play. After "Sleng Teng," everyone was waiting for a new innovation in Jamaica. Well, eventually, the closest thing you have happening to that is the sort of rasta-renaissance movement that starts to come up through Garnett Silk. But there wasn't anything like that in New York. Meanwhile, hip-hop just got bigger and bigger. And if anything you get the rivalries in hip-hop, East vs. West, gangsta rap vs. old-school style. Then hip-hop evolves and you get more complex groups like the Roots or whoever else you have emerging.

Meanwhile, during all this, Jamaican music was kind of stagnating. And then with the New York Jamaican scene, as you rightly said, a lot of people were off the scene, whether they had been deported, or some of them were murdered, or died otherwise. So you had something of a shrinking pool. And then the children of these artists and producers, by and large aren't too interested in reggae or necessarily dancehall. Their identity is mostly hip-hop.

You have a few exceptions, like Roland Alphonso’s son, who started the band Jah Malla. And they had a major label dea,l but that was totally reggae, it wasn't a dancehall thing at all. But I think people like Roland's son was the exception. I think a lot of Jamaicans that migrated, they wanted to maintain those links. They probably saw themselves as Jamaican or New York-based Jamaicans. But their kids probably don't see themselves as Jamaicans. Then in popular music generally, everyone was waiting for something to happen, but nothing really happened that was that significant.

Hip-hop definitely seems like a good place to start to explain dancehall's wane at this time period.

Yes but I think the other thing that happened as well is that in Jamaica, hip-hop started to dominate dancehall production. They really begin to emulate a lot more what was going on in hip-hop. If you think about the era coming into the 90s, you had some of the guys in Ward 21 who started to build riddims at Jammys and in that music, the American influence clearly looms very large. So if you have American music dominating in Jamaica and Jamaican music emulating that American music, then if you are a New York-based Jamaican, then why are they going to want to emulate that?

But someone else we didn't really mention is Bobby Konders. His whole take on dancehall, you can hear that NY element. It's not even exactly a NY element but its something that differentiates it from whats happening in Jamaica. But music that had a wide appeal.

I am curious what the future holds. There's a bit of a roots-renaissance going on in Jamaica right now and dancehall is beginning to appear more in hip-hop again.

I think anything is possible, and people like Ras Kush continue to make unique reggae in New York, but the music industry has shrunk so much. There's a lot more music out there but there are a lot less sells. There’s no impetus. Your recordings become almost more like demos to get you live gigs. Because performances is where you can make money. But that’s not so true on the sound system circuit unless you break through and become well-known individually. But it’s been a long time since anything that noteworthy has emerged from the New York dancehall scene. It’s like you say, it has really waned. Maybe that will changed or maybe something else will happen entirely that's unexpected. Like you will get some other people migrating from Jamaica, or people whose parents or grandparents are Jamaican making music with folks who aren't Jamaican. Who knows, all we can say is, "Watch this space!"