Singer/songwriter Ayo visited the Afropop office on the occasion of her fifth album release, a self-titled, self-produced set of 14 songs that she says best represents her artistic vision. As we spoke, she kept an eye on her infant son, JJ, who mostly kept impressively still and quiet while mom spoke with us. As we were setting up, talk turned somewhat randomly to Russia, so that’s where the conversation began.

Banning Eyre: Have you performed in Moscow?

Ayo: Yeah, many, many times.

Really? You have an audience there?

Yeah, a lot, Yeah, a big audience in Russia. Funny enough, right? Music is a miraculous thing, you know? It has no color, no boundaries, no nothing, it's just a feeling, and if people connect to it, then you find yourself in countries where you wouldn't really expect people would ever like your music.

Well, we can come back to Moscow, but let’s start before that. Tell us about your rather unusual background. You are part of a growing number of artists with hybrid or hyphenated identities. We find less and less of the clear, straightforward stories we used to hear from African artists 20 years ago.

That's very true.

So tell us your story.

I was born and raised in Germany by a Nigerian father and a Roma mother—a Gypsy mother. I pretty much lived in Germany until the age of 19. We left when I was a baby for almost two years to be in Nigeria. My father had the idea to move back and live in Nigeria with all of us, but the system there was just too unstable. It didn’t last.

What years would this have been?

It was in the '80s.

O.K., a tough time then. Military rule.

Tough time, exactly. It was a nice dream to have, but it was difficult, I guess. And then we came back to Germany.

You were probably too young to remember much.

I don't remember too well, no. I actually had to take my dad back to Nigeria when I was 26. That's when I went there to shoot a video there for my first record. My father came with me because I wanted to see my grandma and everybody.

Did he go back much during those years?

He's been back, but when I took him it had been 10 years or so that he hadn’t seen his mom, my grandma. So that's a long time, you know? At one point, he didn't get to go as much as possible. He had so much pressure as well. You know, there are a lot of expectations when you go back. It's almost like Christmas every day, you know? For some strange reason, people they think it's very easy to live in America or in Europe.

I’m familiar with this. I know a number of African musicians here who are hesitant to go home for just that reason. They'd love to, but they can't afford it.

They can't afford it, and then--it's a sad thing in a way--but there's this prestige thing. You want to go back and leave the impression behind that you’ve made it.

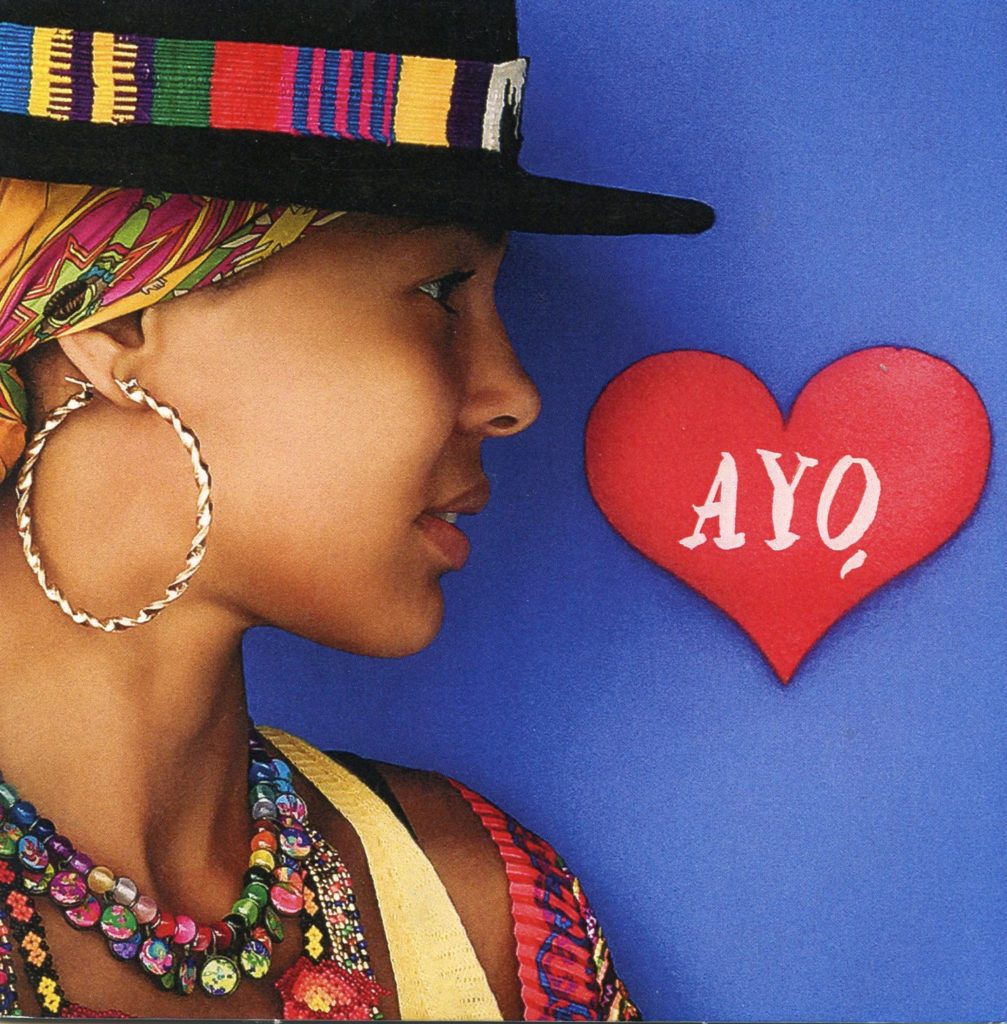

Ayo in the Afropop office (Eyre 2017)

Tell me a little bit about your parents.

How they met?

Sure, and what they did in Germany.

My dad came to Germany as a student. He was studying mechanical engineering. He met my mom because he was a DJ in a club, trying to finance his studies. One day my mom walked down the stairs in the club and there she was! The queen!

I see! [Laughing]

At least that's what my father would say. My parents they have a very interesting story, you know?

I bet they do. So what was it about life with them that made you want to be a musician?

My God, there's so much. But I remember the one thing was when I was 5 years old I saw this album cover of Diana Ross. My dad had all this vinyl, you know, his record collection, and there was this one particular picture of Diana Ross that I loved so much. Her hair was all out, she had her Afro blown out. I had a big Afro, but I always hated my hair when I was a kid in Germany. It wasn't the easiest time growing up in Germany. I don’t think there was a day at school where I wasn't called something.

Where we lived wasn't a big city. It's not even a city really, just a district, and it wasn't the nicest area. There were not a lot of black kids at that time, and not a lot of mixed couples either. So it was difficult.

So that image of Diana Ross just wearing it proud and free like that inspired you?

Yeah. I started wearing my hair like her. I was like, “I gotta pull up the mirror and start combing my Afro down and blowing it out.” I always wanted for my hair to move when I was a kid. And I remember one day we made like a field trip to an island in Germany. We were walking along the beach and it was autumn. The wind was blowing the girls’ hair all over, and my hair wasn't moving! But when I blew it out and wore it down instead of up, it was moving a little bit. And I liked it!

Anyway, when I saw Diana Ross I thought she was so beautiful, and I could see myself in her. I could relate. So at that time, I thought that you have to be a singer. If you want to be on a record cover like that, you have to sing!

Did you sing at that point? Did you think of yourself as a singer?

Yes, I always sang. I always liked music. I remember my father on Christmas or birthdays, I would always get an instrument. Something, whether it would be a xylophone or a keyboard, or a cheap violin. I loved instruments.

That’s great that your dad encouraged you. It’s kind of the opposite of the story we’ve so often heard from musicians. So what kind of music did he play at home?

The music my dad played at home had a huge effect on. He would play King Sunny Ade, Fela Kuti, Jimi Hendrix, soul music. There was this one song I loved so much. "I'll Be the Other Woman" [by the Soul Children]. My parents used to play it and dance to it, and the music just had this powerful effect on me. It made me dream. You know, there was a time in my childhood where it was quite difficult at home. But this music my father played all the time became like the soundtrack of my life, you know? At one point I was separated from my family and I had to go to foster care, and whenever I was away from my father or my mother, it would be a song that would take me back home. That would make me feel like they’re not away. I'm with them. Music has this power. It’s a spiritual thing, and I knew that from an early age. Music was not just a thing that you dance to and have fun with. It’s way deeper than that.

When did you start writing your own songs?

Songwriting was a very natural thing for me because when you start to play an instrument, you want to sing. I always say anybody who plays the guitar, I know that they sing too. Even if they have bad voices...

You are talking to a guitar player with a bad voice right now. [Laughing]

It makes you want to sing, right?

Sometimes...

You know, you play it and you just want to sing, even if you just start humming. But it makes you wanna open your mouth, even if it's just a line, or you repeat something. When you play an instrument, a lot of things come to you, you start to channel things. It's like something is going on between you and your instrument. Anything can come out of you. Even if you had a bad day, you will just sing about your bad day.

So writing songs came to me in a very natural way. But when I really started writing music, I would write songs that were not about the truth. I remember when I was 13 and I would write stuff that was not really meaningful, you know? I was just following that instinct to play and sing. But then when I picked up the guitar, it made me want to sing about my life and let the certain things out. It became more of a therapeutic thing to me, very healing. And then you almost become addicted to it. Because you know you would feel better when you do that. When you don't do it for awhile, you feel kind of miserable.

So how do you get from there to actually recording and releasing albums? That's probably a long story, isn’t it?

That is a long story! Basically, when I was like 16, I used to go to this youth center where I would meet a friend, and we would dance and sing and do all these things. At that point I had a friend who was a DJ, and he would DJ at parties and at a club too. One day he asked me if I wanted to come to the club and sing there. I said, yeah I could do it. But I had to go with my dad because I was just 16

This is still in Germany, in that town?

This was in Germany, but the club was in a city, Geldern. I'm saying city because it’s a city over there. Here it would be a town. It's very close to Holland. But even before that my father would take me to an African club in Krefeld where his friend was deejaying, and where my dad wanted me to sing all the time. My father thought that music was definitely my gift. Even though he had always wanted me to study and finish school and all this, the day he heard me singing for the first time, he decided that studying wasn't for me. He said he believed that that God gave me the gift of music. He was convinced that this was my path to take.

There were times where I wanted to just come back home. When I was 19, I moved to Hamburg, which was six hours away from where my parents used to live. This was in 1999. I moved there because I then had a manager, and he had an office in Hamburg. He thought it was a great idea to come to Hamburg because of all the record labels were in Hamburg and Berlin. I was still quite far away from becoming that singer/songwriter. So in Hamburg, you know, they all had these ideas for me, you know? When you're young, and with a manager or people in the industry, they all look at this young girl and think, “It would be great if she sang this. That song was a big success in the ‘70s or the ‘80s and I think she should sing it again.” They all try to fabricate you. They don't understand that maybe you yourself have ideas, and this is the reason why you're actually even there.

I didn't go there to sing other people's songs, but I had to play the game a little bit. Once they were with my manager, they tried many things, but I was never happy. My dad started calling me “the bridge burner” because I started working with people and then just stopped. I would just quit working with them because I just couldn't do it.

What kind of music were they trying to steer you to?

Pop. Bad pop. Because I think there's good pop.

Yeah, of course.

But that was very bad pop. It was terrible. I remember being in the studio, and trying to sing over whatever they produced, the beats and all this. I didn't like it. And my father was telling me, “You know, it's a beginning...” And at one point I had to tell my dad, “If this is what I do, nobody's going to take me seriously when I do what I really want to do.” My father didn't understand what I was saying. But then one day I had like a nervous breakdown in that studio. I was really rude to the two producers who were there. My father was quite embarrassed. “You have to respect for your elders!”

Right. He's coming from the tradition.

And I didn't have that anymore. So when I stopped working with them, my father was kind of shocked. But I think it was the best thing I did, because that is what pushed me more and more into really just picking up the guitar.

Paris, le 30 juin 2017

La chanteuse Ayo

How did you release your first album?

I was 25, just a few months before I turned 26. It was incredible because at that time I was in Paris. I decided to leave Hamburg when I was 21, and go to London first. From London I went to Paris.

Did you speak French?

No. I didn't speak French.

So why Paris?

Because I had a best friend; she's like my sister. She is a designer in Paris. And she asked me one day if I could come and model for her, and then play a song with my guitar. And when I did that, people liked it so much, and I met this guy who was organizing events and all this and he asked me if I didn't want to stay a little bit and play another event. And so I ended up working with him. For the first time ever, I found myself in a room with like, 300 people sitting down on the floor, listening to my music. It was crazy to me. It's the first time I experienced that. I decided to stay in Paris because it was the place where people were inviting me. I was even invited to radio stations, but I didn't have record deal. I wasn't signed. I was an independent artist. But that's the way I actually got signed to Universal. There was this big magazine that decided to write a story on me. I didn't know at the time, but this was the magazine that the record labels tried to get their artists into, you know? Funny thing: When I signed with Universal, I was never in that magazine after that, never ever again.

But it did what you needed to then.

Definitely, because they gave me two pages and I did this pose that looked like Bruce Lee. You know this karate pose with my big Afro and that's how I ended up signing with Universal. It was an amazing story because the person who signed me… I was so lucky because he was a real music lover. He had worked with Abbey Lincoln on Blue Note, and he was really somebody who had good taste in music. It was a big blessing. That was in 2002.

I know your time is running short, so let’s skip to the present. You did three albums after that first one, and that brings us to the new one. It has a very unique sound, and I gather you were more deeply involved in the production this time. Tell us about the new album.

I was so lucky to be able to release these four records with a big record label. But after my fourth record, I was ready to leave. It was time to start a new journey. I had been 10 years signed to Universal Records.

Was it because you felt that they were directing you in certain ways, and you wanted to be more experimental?

Not really. I consider myself really blessed to have been able to work with people who didn't try to box me in. From day one of my recording career to now, I was free to do what I wanted to do. But sometimes you can be free to do what you want to do and still you get certain things that you have to do because you work with a producer. So, it's freedom, but not total freedom. So this one here is the first time where I just started working on the record myself. I had no record label. I felt like it was time to leave Paris. Maybe that was my Gypsy blood. I'm a very restless person. So I left everything behind and came to Brooklyn, because I wanted to be a mother to my kids. I just want to take them to school and do the normal things, you know?

So I did it for a while, and then I felt miserable. I felt like “Oh my God, I need music, I need to play music, because if I don't play music, I'm not gonna be a good mother.” So the kids would go to school in the morning and I would just start to produce myself, basically in my bathroom. I even recorded on my phone. I did that everywhere I would go to. At one point I had to go to Paris for a few days. I decided to add this little tune on my old piano, standing in my apartment. And I recorded myself on my phone. I had an Apple G interface for my phone to use so I could record to Garage Band on my phone. I had the tube mic connected to that interface connected to my phone, and so I just recorded myself whenever I could. To the point where all of a sudden, I had a lot of songs. I was in the process of meeting a new record label, and I told them what I was doing. They asked me if I could play some of the songs for them, and they really liked it. They thought it was a great that I was recording it all by myself and doing everything myself. They offered me a license deal, which was perfect for me because that meant that I could really do exactly what I wanted to do.

The record has a very spare sound. There's a lot of reggae in there. But it's not like straight-up reggae. It’s more like an undercurrent, and the sounds are very interesting. And this is all coming from you, right?

Definitely. It's a 100 percent the way I imagined it. I can't even say the way I imagined it. I would rather say the way I felt it. I just wanted to do whatever felt right. I just had fun, you know? Without having a concept or expectations or without even thinking. I didn't want to think at all.

Let's talk about a couple of songs, like the first one, "Oh Nothing."

“Nothing" is a song that was very important for me because, at the time, I understood something very important about myself. I used to say, “I've never been drunk in my entire life. I've never done drugs. I mean I'm obviously not an addictive person, but that's not quite true. Just because I don't drink and don't do drugs doesn't mean I'm not an addictive person. There was a time of my life where I bought so much, so many things. That’s an addiction as well. I did that because I wanted to make myself feel better. I went through a lot of personal problems at that time, with the father of my kids, you know? I guess it’s the stuff that a lot of people go through--being cheated on and all this. First thing you think is “Something is wrong with me, as a woman.” And you become bitter, and start to change. It's not good you. To change, you turn into somebody else, I would almost say. You forget about yourself because you feel like yourself wasn’t good enough. So I started buying stuff to make myself feel better. I shopped myself numb.

I can almost say numb and dumb, because it's really stupid to do that, you know? And it didn't fix anything. It didn't make me a happy person. So at times I had no money, and I had to sometimes jump the metro in Paris, or take my guitar player to a restaurant and eat in return. I know those times. But I also loved those days, because I was free! I was free and I was happy! I never had a problem. I never had worries. But then, all of a sudden, you have success and you have access to so many things that you never did before. People think, “Wow, it's this platinum-selling artist! This star.” That’s all they see, but you don't feel all lucky. A star to me is like a shining thing. But you, you don't feel like you're shining at all. You're pretty much in the dark. And, there's nothing fancy about that.

So in this song, I'm saying that I have nothing. When I actually had it all, I had nothing. When I had none of these material things, I had everything.

That's great.

You know the law of joy? No money, no dress, no Chanel bag can give you joy, you know? That's not real. That's only temporary.

Let’s talk about the song "All I Want.” You know, the background singing on that reminds me of the old Wailers, you know? Peter and Bunny.

Yeah! [Laughing]

Am I crazy?

No you're not! I'm happy you're saying that because when I recorded the song, I was like, “Oh, it gives me this old Wailers feeling.”

It’s absolutely fantastic, a beautiful song. I guess we need to talk about about “Paname” because you’ve made this great video for it. It's your ode to a certain side of Paris, isn’t it?

Yeah! “Paname” to me is like a love letter to Paris, because I owe Paris so much. It has given me so much. Basically paname is a slang word for Paris; Gypsies call Paris Paname. I always say Paris is the Champs d’Élysée, Place Vendôme, and all the beautiful areas. Paris itself it sounds so fancy already. But Paname, that to me is the real Paris, the African Paris. It's the 18th, the 10th, the ninth district, these districts where you find people of all colors. You have a lot of Jamaicans, and it's funny because Jamaica is such a tiny island, but they're everywhere in the world, you know? I mean Nigeria is a big country. Of course they're everywhere, but Jamaicans? They’re really everywhere, and they have such a beautiful culture, you know? Reggae is a big thing in Paris as well. And I think that's what I love—all these different influences. You have that same thing in New York, but New York is big! Paris isn't. Paris is really tiny [Laughing]. I mean you can't really compare it to New York! It's just so small! You can walk everywhere! You cannot do that here! I mean sometimes I cross the bridge because I live in Clinton Hill. I would cross the bridge and walk when I was pregnant with him, my last baby. But crossing the bridge to Manhattan—that's,a long walk. That same walk, I can do every district in Paris.

And that's what we see in the video. There's a rooftop dance that’s really lovely.

When do you know that you're in Paris? I think it’s when you're on the roofs of Paris. That's when everybody understands, “Oh, this is Paris.” The magic is up there, really.

Then you have this powerful song, “Boom Boom.” How did that come about?

“Boom Boom” is a song I wrote when they killed Mike Brown in Ferguson [Missouri]. I'll never forget that day. People were talking about the riots in Baltimore, and I was like: this is crazy! I went home and turned on the TV and there were huge riots. People were mad. Everything happened so fast. How can they shoot a young boy like this? And six times, not just one time, and his hands were up. It was just so devastating. I felt so bad for the mother. When I turned on the TV, a journalist asked a woman with two kids what she would tell her kids about the police and all this. She said, “I'd tell my children, ‘Whenever you see the cops, don't run! Just be still. Don't do anything. Just be still, and wait until they're gone.'” That was shocking to me, because what do kids do? They play! They jump, they have fun, they run around, they do crazy things no matter what color! They all play the same games! You have to tell your child, when the cops are there, “Don't jump, don't run, don't do anything. Basically, don't be yourself.”

You know, it's interesting. When I heard this song first, I didn't know the context, and I thought it was about Nigeria. We were there recently and heard a lot of awful stories about summary killings too. I guess this applies in a lot places.

In a lot of places. Many countries have a problem with authority. If you think about it, you're wearing a uniform and you can do whatever you want to. And in America it's crazy because everybody knows it's not right. It’s very unfair, and “Boom Boom” talks about that. It's dedicated to all the mothers who have lost a child due to police brutality.

Sorry you have to run now. I look forward to talking more in the future. And congratulations on the album.

Banning and Ayo