Bombino is unique among the Tuareg rock acts so popular on the global tour circuit these days. He’s a singer/songwriter/guitarist from Niger, a man on his own, not part of a collective like Tinariwen, Terakaft, Tamikrest, Imarhan or Amanar—all of these Tuareg guitar bands from neighboring Mali. His concerns are similar: a deep love of the nomadic Tuareg lifestyle, despite its many hardships, but also a sense that this beloved lifestyle is under threat, both political and cultural. The nomadic Tuareg are actually a diverse group, and their history in Mali and Niger is somewhat different, notably less combative in the latter country. But when it comes to modern music, everything flows from the experience of rebellion. A combination of conflict, drought and lack of opportunity drove many Malian Tuaregs into towns and encampments in Libya and Algeria in the 1960s, ‘70s and ‘80s. That’s when they got exposed to rock music—Santana, Hendrix and, the favorite, Dire Straits. These exiles were denigrated as chomeurs, unemployed rapscallions, but they took the term as a badge of honor, dubbing the new guitar music ishumar.

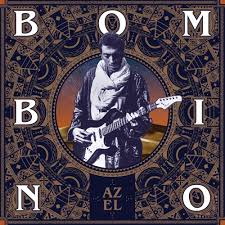

Bombino’s third studio album, Azel, takes its name from a village near Agadez in northern Niger, where the maestro enjoyed a part of his youth before being driven into his own period of exile in Burkina Faso. The session comes on the heels of Nomad (Nonesuch), Bombino’s acclaimed 2014 release produced by Dan Aurbach. Aurbach certainly passed on some expertise in achieving gloriously roaring solid-body electric guitar sounds, and that shows here, as this set of 10 songs moves back and forth between charging electric romps and elegant acoustic numbers, like the poignant closer, the title of which translates “We Are Left in This Abandoned Place.” The track conveys the sense of musicians enjoying music, clapping along, around a fire in the desert, even as it laments the loss of that very sort of experience. Simply beautiful.

But back to those electric romps. “Akhar Zaman" (This Moment) sets things off with a rocking roar, again dwelling on the loss of traditional ways. “Iwaranagh (We Must)” slips into a quasi-reggae, quasi-soul groove that lifts beautifully, while calling on Tuareg people to repair their embattled culture. This is one of two covers of Tinariwen songs here, the only interpretations. The other, “Iyat Ninhay/Jaguar (A Great Desert I Saw),” is the centerpiece of the album, a righteous electric jam culminating in a lengthy guitar solo from Bombino that opens with sensitive melodiousness and resolves into raging ecstasy.

It must be said that the grooves on this album kick like no other Tuareg band. Kudos to American drummer Corey Wilhelm, the only member here not from Niger, for that. Whether cracking out 12/8 time or digging into the lugubrious, weighty 4/4 of numbers like “Iyat Ninhay,” Wilhelm grounds this road-seasoned ensemble admirably, animating and leavening the hypnotic blast of even the densest mixes.

Bombino’s vocal is reedy and elusive, sweet by comparison with the sometimes rough, grumbling vocals on other ishumar acts. But Tuareg sweetness always comes at a price. Among an ode to martyrs of Niger’s 1995 Tuareg uprising, and calls for unity among a tragically divided people, there are love songs here. But love is no picnic for nomads in a strictly hierarchical society. It means transgressing social boundaries, and dealing with long, agonizing separations. This is music of hope and longing, resolve in the face of great adversity, rendered with spirit, confidence and a sheer passion that any rock band would die to achieve.