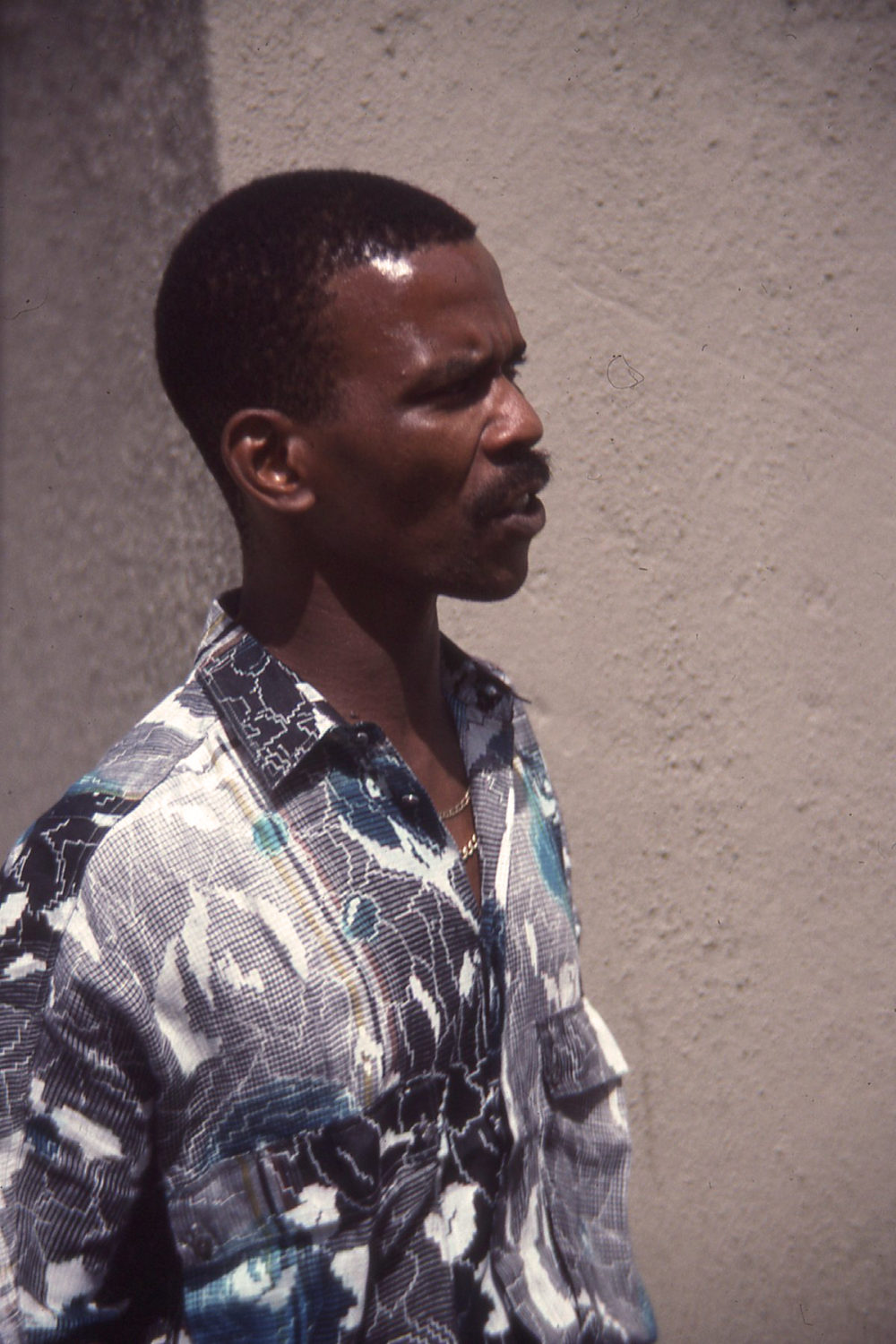

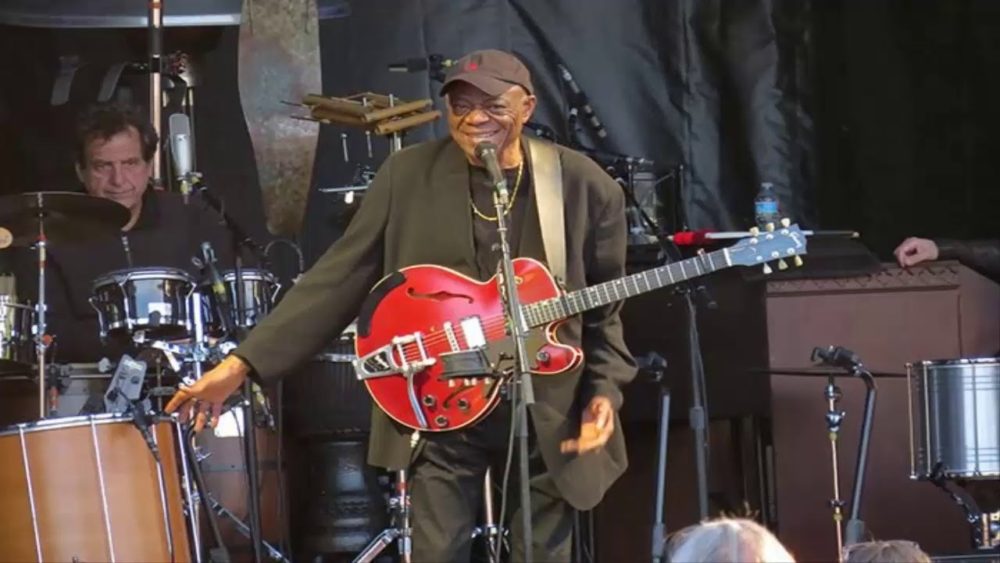

Bakithi Kumalo is a legend of African music. The continent’s best-known bass player, immortalized for his ear-popping break on the song “You Can Call Me Al” from Paul Simon’s landmark 1987 album, Graceland, Bakithi has made his home in the United States for the past 30 years. He has continued to play and record with Paul Simon, and been an active member of a coterie of A-list South African musicians in New York City. Graceland brought contemporary African musicians their first taste of Grammy Award recognition. So as 2018’s Grammy Awards approach, Bakithi and the South African All-Stars return to B.B. King Nightclub and Grill on Sun., Jan. 21. Afropop’s Banning Eyre reached Bakithi at his current home in Bethlehem, PA. Here’s their conversation.

Banning Eyre: Bakithi, I just realized that it was 30 years ago this month that we first met in Johannesburg.

Bakithi Kumalo: Oh my God. And my son was there. He had just been born.

I remember him.

He’s 30 years old now. He’s about to be 31.

Of course. He was just a baby then. We met at that Jo’burg club, Kippies, if I remember correctly.

Kippie's. Yes. I was doing a project there with Sipho Gumede.

And here we are, 30 years later. I saw you recently playing with Dorothy Masuka at Town Hall. That was a nice set. So listen, I’m not going to ask you to summarize 30 years, but when you look back, did you ever imagine things would go they way they’ve gone? Touring the world with Paul Simon and Hugh Masekela, and winding up living in the U.S.?

Well, you know, it’s not what you look for. It’s what you make. All these years, I’ve been trying to stay ahead, learning and growing as a musician and I’ve been really grateful to be working with such great musicians. They trusted my playing. I was on tour with Mickey Hart, Randy Brecker, Herbie Hancock, Cyndy Lauper, all after Paul. So my life has been really educational. It’s destiny. It’s where I’m going. I’m 62 now, and I’m still going. Because you just never know. You can’t stop learning. You’ve just got to keep going. And then having two daughters in college, and my son in South Africa has a baby now. So I’m a grandfather.

That’s beautiful.

And then of course, living in this great country. After South Africa, this was the best place to jump into—to leave a great country and then to come to a great country. It was from the struggle to the struggle too. Because now when I see what’s going on now, it’s a whole different story.

You must see current events here from a different perspective after all you’ve been through.

It’s true. I’ve seen it all. To go through two presidents, the greatest presidents [Mandela and Obama]. I mean, I tell you, I’m the greatest and happiest man, to split 60 years in two.

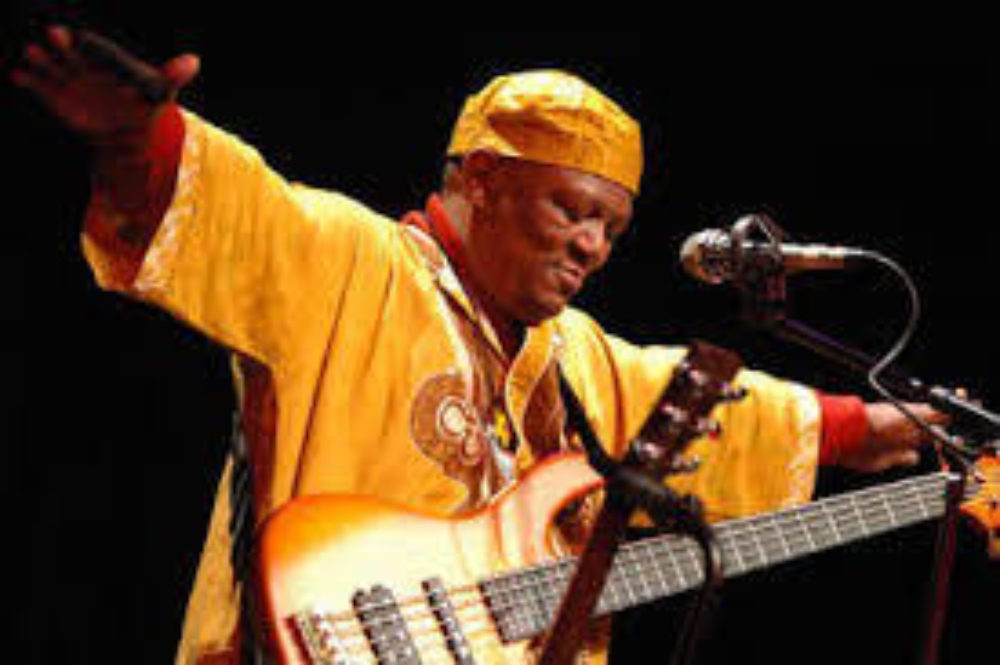

You’ve got a concert coming up this weekend at B.B. King. What’s the band going to be?

Well, the band is the South African All-Stars. We are trying to do a lot of work together, because they’re like my old friends and we grew up together. You know, Morris Goldberg from Cape Town. David Bravo plays piano; he’s like my musical director. And then Mark Portugal, the drummer, he used to be my daughter’s teacher. And when I heard him play, as a bass player, I said, “This is a drummer I would love to play with.” I took him to South Africa to the Jazz Festival and that was amazing. So it’s pretty much the South African thing, mostly instrumental, and then we’ve got the kwela thing going on, and I’m singing. It’s just to celebrate the new year and hopefully bring the South Africans in. The band is really magic. You know, Morris Goldberg played the penny whistle on “You Can Call Me Al.”

Oh, he did? I had forgotten that. That was Morris.

Yeah, that penny whistle you hear—that’s him. You know sometimes it drives people crazy. You know, being a South African bass player and a black guy, how can I use these musicians? But they’re consistent. And they’re the only South African musicians I can call on that can practice and read music. There’s nothing South African they can’t play. And when I call West Africans, the language is a problem. But I love this band. We played with Hugh Masekela for many years, and Miriam Makeba. You know, me and Morris, we met in Zimbabwe years ago and we exchanged numbers and when I came to New York I called him for some gigs. And the rest is history.

I’ve seen Morris a number of times. It’s so great to have such classic South African musicians here in New York. It’s a treat.

Yeah, and they went to school. So it’s much easier. When I say, “Let’s come and rehearse,” I say when, they show up and they drive. You know, some of these musicians, it’s like, “Well, can you pick me up?” And I say, “No! I don’t have a car.” But these guys are reliable. They’ve been around for years and we’ve been all over the world together. And Morris, he’s 82 years old.

Wow.

So I’m trying to get more from him, because after him, I don’t think there’s another guy who can play penny whistle like him, unless I bring a guy from South Africa. But this guy, he’s brilliant, at 82.

Amazing. I understand that this January 21st show is a kick-off to Grammy week. And it’s fitting, because I think you and the Graceland band were the first Africans to win a Grammy, right?

Listen, you know, I do this for my home. I don’t have to have the Grammy. I don’t have to have money. Because I’ve struggled so much, and this is a good lesson for our people back home. Don’t sit there and think that things are going to come to you. You’ve got to find something. You’ve got to go look for something. And when you play music, no drinking. Just focus and try to help the others you’re playing with. Right now, I’ve got four Grammys: with Herbie Hancock, Randy Brecker, Paul Winter and then Paul Simon. But for me, it’s about what Nelson Mandela did for us. I’m the continuation of that. Because watching him, being the greatest man, he taught me how to be a great musician—without talking, just thinking with your brain and then using your skills and the gift that you were given.

And a lot of heart too.

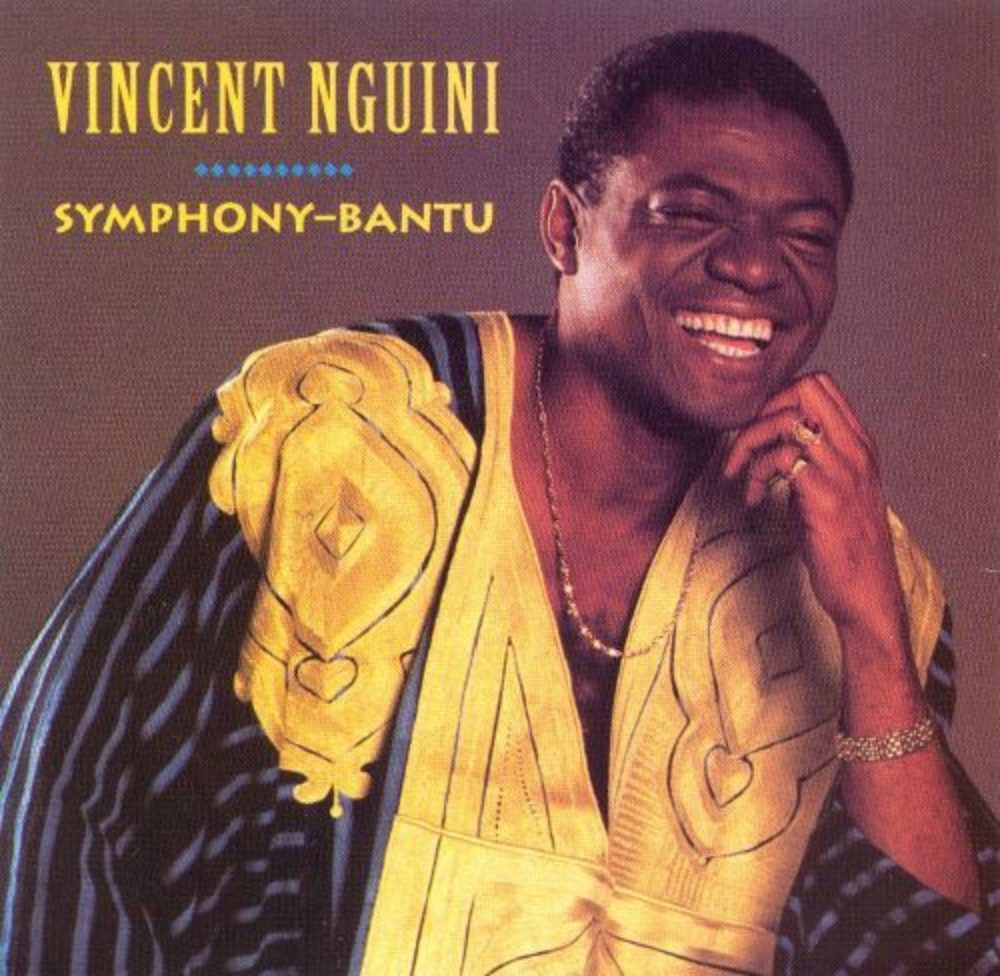

That’s right. That’s what I’m doing. Today, I’m the only South African standing on Paul’s stage. I mean, we lost Ray Phiri [July 12, 2017], and the Cameroonian guitarist, Vincent Nguini [Dec. 8, 2017].

Oh yes, such big losses!

So I’m just so grateful. I’m the last one to leave the stage. I’m just so glad I put South Africa in the mix. The timing was right, and now the younger generation can continue it.

It was so sad to lose Ray and Vincent last year. I’d love you to say a word about each of them, because you knew them so well.

Well, first of all, Ray was a big influence on me. He was always talking to me. He said, “Listen, if you want to feed your family, and you want to play music that people can understand, this is what you do: You play simply and respect sessions. When people call you for the session, don’t come with an attitude, don’t come drunk, don’t be late.” You know, he was like my mentor, and every time he would just talk to me, "No, you are going to sleep in the studio because I've got like 20 songs to work up." And I'm like, "Oh, my God. I’m dead!"

Ray was just an amazing guy. But you know, it's also how you take care of yourself. Because you know, smoking cigarettes and drinking cognac every day, these things come back to you later on. They eat a body like crazy. And you start getting sick. And you know, in South Africa, most people, they really don't know. Because if you don't go to the doctor, you won't know. And then you just drop dead. I've seen Ray really going crazy with drinking and smoking cigarettes. You know he was playing a tour before he passed. I was in South Africa in 2012 for the anniversary of Graceland. We were talking about coming back. We are the people involved with Graceland, so this is what we were going to do. But, you know, the sickness beat him. And then I was not there. I was going to go home and do a treatment for him, but it didn't happen.

That's too bad.

Vincent is a whole different story. I met this guy, the first Cameroonian guy, and it was not a good meeting.

It wasn't?

Oh no. It was not a good meeting. He's not a person who talks, unless you speak French. It was kind of hard. And then he had to teach me his Cameroonian bass lines. We were busy in the studio, and I said, "So show me what there is the one."

And he said, "I don't understand. Which Africa you come from and you don't know where the ‘one’ [the downbeat] is."

And I said, "Well, you know, in your country you have like 9/8, and 7/4, 6/8. In South Africa, we have 4/4. Simple."

And he said, “My friend, you have to learn. You have to watch me. You have to listen to me." Oh my God, there was so much pressure. So I couldn't record one of the songs, the song called "Cool Cool River" from Rhythm of the Saints. It is in 9/8. I couldn't record the song. And I said, "Vincent, you are going to record the song and I'm going to take the tape and go over to the hotel and I'm going to learn it." And I just did that. And Paul put the tour together, and then the song was recorded, and Vincent became my friend. And he said, "My friend, now you can live in Cameroon."

“Cool Cool River." What a beautiful song, and what a great story.

And then, on tour, on the buses, he would play me some stuff from Cameroon, and I wouldn't touch the bass until the sound check. I would just listen and say, "Wow, what are these people listening to?" So I just absorbed all that stuff and I learned so much. Vincent gave me a lot, man. He gave me a lot. And it's just a loss. Such a loss. There's no one like him. And Ray was the same. You know, Ray was not an educated musician. He couldn't tell you what chords he was playing, but the ideas, and the stuff he played, it was just amazing.

You can hear it. Ray was so musical. It's great to hear those stories. I always meant to do a guitar interview with Vincent, but unfortunately, I never got around to it. He was such an incredible guitarist.

Oh, no. This guy. Nobody could get around him. Sometimes I would call him for the gig, I would say, "Vincent, I have a gig.” He would say, "My friend, how much does the gig pay?" And I'd say, "Oh, about $250." And he would say, “No, let them get some young guy.” [Laughs] You know, he was just dignity. He had his own private moment. Even on the plane, he wouldn't talk to us very much. He would be quiet. We just didn't really know anything about him. He had some really dark side that we never knew. It's a shame that he got sick.

What was it?

Cancer. But I think he had diabetes too, and then he started breaking down. His body started to break down. And then I think he had kidney problem. And from there, he was just spending time in the hospital. We did a tour last summer. He came on to do the last two shows of the tour. He played two shows and went back to the hospital. And that was it.

You could really tell that his playing came from a deep place. So who is Paul going to use now?

I don't know. I feel like this is the end of the journey. I don't think there's anybody that can replace him. There are people that can do it because of the paycheck. But the sound, and the dedication. This guy was a big part of this band. His sound, when he would start playing, and he would talk to Paul and try to educate Paul about stuff. There is nobody that's going to talk to Paul now. Me, I just stand back and play my part. But he was the force of the band.

That's interesting. He would stand his ground and assert himself in a way others wouldn't. Fascinating.

Yes. He was the force of the band. But now, I'm sure Paul is talking to a bunch of people. But it's not going to be easy. I'm trying to think who could do this in South Africa. Maybe Louis Mhlanga from Zimbabwe.

Yes. He's great. I could see that.

I think that guy would be the guy, but you know, living in South Africa, it's hard. It's hard to communicate with people. With the Internet and all. It's kind of frustrating. So I don't know. They might pick a guy here. And to be honest with you, I'm now the oldest member of this band, but I was never asked about anybody. "Do you know anybody?" You know, even when Steve Gadd left, there are plenty of drummers like do this gig. But the people from the band, they always want to bring their friends. Same thing with this guy. Our percussion player knows a lot of people. But no one has called me to say, "Do you know any African guys?” Anyway, I'm just grateful that I'm still on stage and playing. And hopefully, when Paul retires, I'm going to fly myself back home and try to be a mentor to these young musicians.

So you would like to go back and live in South Africa at some point?

I want to go back, because I've been gone for a long time. My daughters are in college now. And I have a sister there. I knew about her, but we never met until 2012 when we went back for the 25th anniversary of Graceland in South Africa. I got this call. And I was like, woah! I remember my mother used to talk about this, but I was like 10 years old. I would ask, "Where is she?” But finally, my sister's family, they went online and Googled my name, and they called me. There was a lot of crying on the phone. It was the Graceland 25th anniversary, and also my sister’s 60th birthday. But we had never met.

Why was it that you never met before?

What happened was, when my sister was born, my father denied her. He left from Johannesburg to Durban. My father was from Durban. This was before I was born. So my father left her, and my mother got really angry. You should not just leave the child and not support her. So my mother called my father's family in Durban and said, “I want to see you. I have something for you.” And then when she came, they met, and she handed them the baby. Then she went back to Johannesburg. And I was born two and a half years later. And then my father left us. So my sister was raised by my father's family, and I was raised by my mother's family. Actually, my mother was not there either. I was really raised by my grandmother and my friends, my street friends, and music. So we didn't know each other.

But after 2012, the 25th, we connected. I went to Durban a couple of times and met my nieces and nephews. So I'm trying to connect. Because I miss them. Also, I have a granddaughter there, but I can't bring my son’s family here now, because of the way the situation is now. My son tried to get a visa and he was denied. They asked him, “If you go there, you don't have a job. How are you going to feed yourself?"

And he said, "No, I don't need to feed myself. My daddy's there. And I'm just going there for like a month." But they denied his visa. So now it's my turn. Because I want to get old at home. You know, I'm just getting beat up. The age is catching up with me. So there are many reasons. I want to go and teach, and bring my skills to the kids, and show them, and talk to them, go to schools and say, "Look, this is what saved me. Leave drugs alone. Leave alcohol alone. Count on what God gave you, your gift. And music will take care of you, like it did with me." So that is my speech. And that's the reason I'm going home, and of course, I'm really homesick. I'm homesick. At this stage, you know, the energy is not the same.

I know what you're talking about. Well that's great, Bakithi. I know you'll be a great mentor and a great role model for young people.

But also, you know, I'm a citizen here now, which is unbelievable. Thirty years in South Africa, and 30 years to become a citizen here. Now, going to South Africa, I just want to make that relationship. When it's winter there, I'm here and there it's summer. If I can do that…

You can have endless summer. Thanks so much, Bakithi. Such a pleasure to talk to you. If you like, I will direct people to your website.

Sure. It’s bkumalobass.com. Nice talking with you.

Absolutely. See you at B.B. King on Sunday, January 21!