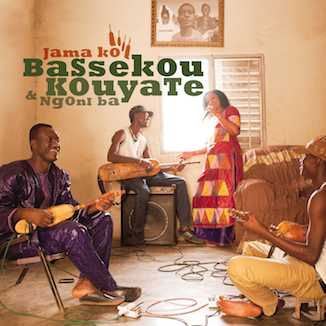

Bassekou Kouyate, the pre-eminent master of the humble West African spike lute—called ngoni in Mali—offers a grand summation of musical, personal, and even military history in his third CD with the group Ngoni Ba. First, there have been some changes in the band—still a family affair, but now even closer family with the addition of two of Bassekou’s sons, Madou on bass ngoni and Moustafa on ngoni ba—that’s the “big ngoni,” though not as big as the bass instrument, effectively created for this group. Abou Sissoko now plays what we might call the tenor ngoni, the one in between Bassekou’s small instrument, and the ngoni ba. The entrancing weave of plucked string textures, unstoppable grooves, and sensational vocal performances from Ami Sacko (Bassekou’s wife) and some terrific invited vocalists, is every bit as brilliant and satisfying as on the earlier Ngoni Ba releases. What is different this time is the context.

After months of practicing for the recording session, the musicians gathered at the legendary Studio Bogolan in Bamako literally on the day of the military coup that overthrew the government of Alpha Toumani Toure, known to Malians as ATT. It was a complex and trying moment, and Bassekou’s first response was to plug in his distortion pedal and lead a furious, impromptu jam that became the song “Ne Me Fatigue Pas (Don’t tire me out),” just one of many barnburners on this CD.

But there is deeper reflection on the multi-faceted crisis in Mali woven throughout these 13 terrific tracks. Bassekou explicitly rejects Islamist efforts to ban music, claiming that if they were to succeed, they would “rip the heart out of Mali.” That message is reflected in two songs celebrating historical Bamana leaders who resisted or defied the 19th century jihadist Cheikh Oumar Tall. On the first, “Sinaly,” guest vocalist Kasse Mady Diabaté adds his august voice to a sizzling ngoni jam. On the second, “Segou Jajiri,” praise goes out to a Segou warrior who drank millet beer, in defiance of Tall. It seems Bassekou is standing up not so much for alcohol consumption as for personal freedom from religious tyranny. The song starts with Ami Sacko laying out long notes over a chugging groove—nice contrast—and ends up in something like a Congolese dance groove, appropriate for a song involving alcohol.

The gravelly voice of Zoumana Tereta figures satisfyingly into a few of these songs, including the bubbling string jam “Dankou,” and the tripping 12/8 lope of “Kensogni.” Here, a deep weave of ngonis sets up a thrashing solo by Bassekou, and Zoumana’s gloriously ragged vocal delivers a morality tale about corruption, jealousy, and lies—perfect fare for what is ailing Bamako these days! Bassekou also shows solidarity with the suffering in the north of Mali in an anti-war song created with the great lady of Timbuktu, Khaira Arby. The song is “Kele Magni,” and it unfolds as a conversation between two women, Arby and Sacko, who have no use for warfare as an approach to solving problems. You feel that in every note—no translation required.

Sacko’s tour de force comes on the slow, steamy Bamana groove, “Wagadou.” Her paint-pealing vocal performance praises wise leaders and patrons in breathtaking fashion. This is the one song in this session where Bassekou takes his ngoni solo using a clean natural tone, with no distortion or other effects. It’s a throwback in more ways than one, and likely to send chills down your spine.

There’s a playful duo between Bassekou and Taj Mahal—his friend for 18 years when this recording was made. And the session ends with a sweet expression of thanks from Moustafa, the youngest member of the group, to his parents. But the real passion, and greatness, of this album lies in its visceral, and virtuoso response to the tragic unraveling of Malian civil society—the very thing that griots like the musicians of Ngoni Ba live and work to avoid.