Nigeria currently dominates the African pop music market with the sound known as Naija pop or Afrobeats. Obviously, this music has many fans, but it also has critics, who regret its fixation on wealth and style, and its relative absence of social or political messages. Among those critics is Beautiful Nubia, a singer/songwriter/bandleader who has cut his own path in Nigerian music since 1997. With some 13 studio albums to his credit and a dedicated fan base in his hometown, Lagos, Beautiful Nubia thrives as a beloved maverick in the city’s dynamic music scene.

While researching Hip Deep in Nigeria, Afropop’s Banning Eyre saw Beautiful Nubia and his band performing in an abandoned house belonging to a fan. The setting was humble but atmospheric, and the crowd of 100 or so who showed up were absolutely intent on Nubia’s every word, at times singing along with him and his band. The next day, Banning sat down with Beautiful Nubia for a wide-ranging interview. Here’s their conversation.

Banning Eyre: To start, please introduce yourself.

Beautiful Nubia: My stage name is Beautiful Nubia, but my real name is Olusegun Akinlolu. I always joke that you can dance to the sound of my names. I was born in Ibadan in southwest Nigeria in 1968. I studied veterinary medicine at the University of Ibadan and worked as a vet for about eight years before I became a full-time artist. Of course, I was a musician long before. From early childhood, I always knew I was going to do music. You are nine years old, and you know you have a gift for songwriting. You can hear melody and bend it around, and it becomes yours. So I always knew I was going to play music. It was just a question of when and how.

In Nigeria at that time, the ‘60s and ‘70s, you had to be a lawyer or doctor. I was a kind of all-around academic star, so it was natural that my teachers and parents would push me towards something professional. My teachers told me, "You can be a singer or a dancer or whatever you want to do in the arts. But think about it. What if the arts don't work? What if there's an economic crisis? What is the first thing that goes? The arts. You need something you can fall back on." They pushed me to learn a trade, so there would something to fall back on.

How did you break into music?

I had an uncle who worked at Afrodesia Studios, the old Decca Studios in Lagos where all the great artists of the ‘60s and ‘70s used to record: Manu Dibango, Fela Kuti, the Lijadu Sisters… There was an engineer there and I pestered that man. I was 11 years old coming to Lagos, and I wanted to be recorded. So eventually, when I finished my National Service in 1993, I did a demo and I tried to shop it around to all the record companies. Sony, PolyGram, and a few others were still around, but those were the last years. All the major labels left after that. Nobody took my demo. My music was too topical. That's what they said. These were the words they used. "Too topical. People don't want to hear that. Music should make you feel good.”

They told you this in 1993?

Yes. They said, “What is reigning now? It's fuji or gospel music. Anything beyond that is not going to sell.” So I decided I was just going to have to do it my way. I set up my own recording company, my own production outfit called Eni Obanke Music. And I released my first album in 1997.

[embed][/embed]

What does Eni Obanke mean?

It means “he or she who is pampered by the king.” I coined that name. I made it up. The one who is pampered by the king or loved by the gods. Because as an artist you have to feel that you're special. I don't think there's an artist out there who doesn't have that kind of arrogant self belief. I mean that's what drives us to do the things we do. So I always thought I was special, this fellow was blessed with all these gifts: I must be a special messenger from the gods.

That's interesting. I have been struck by all the self-promotional titles in Nigerian popular music. King, Doctor, Sir, Chairman, even Cardinal. On and on. I think that comes from what you're talking about. So what happened with that first album?

My first two albums got a mixed response. I was still working as a vet, so I think people couldn't see beyond that. This Dr. Akinlolu person, who spoke in a very technical way, now is wearing a fancy shirt and dancing on TV. What's going on? But the second album in 1999 got us a nomination at the Kora Awards. The Kora Awards at that time was the biggest thing in Africa. It was at Sun City in South Africa. That was the point when people started thinking, maybe he's got something. Because the Kora Awards was all about King Sunny Ade and Femi Kuti, and then this unknown guy comes up.

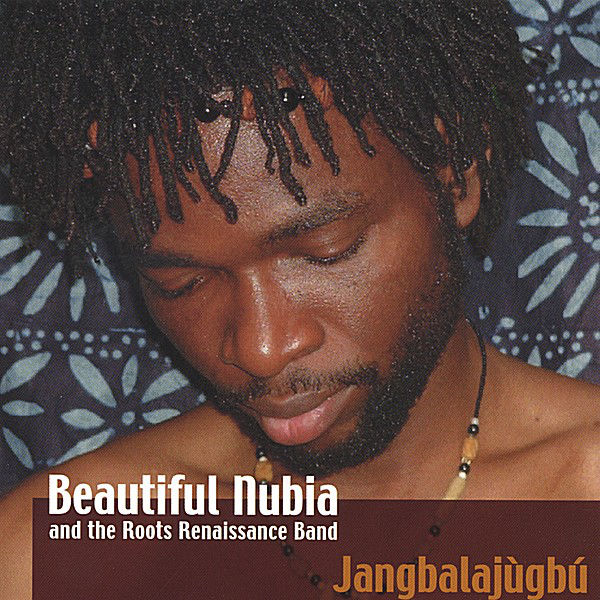

But my third album, Jangbalajùgbú, in 2002 was the real breakthrough. I knew I had a sound I wanted to produce that wasn't coming out. On the first two albums we used a lot of computers and programming. I've never been a big fan of that. I grew up in the ‘70s. I was used to a huge studio with great equipment. My father had a music store where I sold records from the age of 5. I still remember the smell of a freshly pressed LP jacket. We used to have some interesting jackets. Osibisa had some of the best.

Jangbalajugbu (2002)

Jangbalajugbu (2002)

I remember those.

This is what I grew up with. Now to come to a small room and you're just chiseling things out on the computer, I didn't like it. But I didn't have a firm footing yet, so I let the engineer decide a lot of things. I would tell the producer, "I want this sound." And he would say, "No, it won't work. We’ll do this instead." So the first two albums in a way, I didn't really feel that that was my sound.

Then on Jangbalajùgbú, I used my live band. I put together a live band against a lot of opposition. Even the musicians were telling me, "Band music is done. Nobody does bands. It's too expensive to maintain." But I got together 14 guys and we started working together and we recorded that album. And you know, when it first came out, people said it was a new sound. It didn't sound commercial. It wasn’t going to go anywhere. But that album sold millions, and it's still selling now. It's our biggest seller.

Fascinating.

It is an iconic album. If you ask Nigerians, they will tell you. I think it changed a lot of how people look at music in this country. We used to have people like Fela, Orlando Julius, Monomono, that whole generation of people doing Afro-soul, Afro-jazz, Afro-funk. After that era, everything just seemed to go down. There was all this reggae in the ‘80s and ‘90s, and the pop guys were all trying to sound like Michael Jackson, trying to do disco and soul. Then we came along with this fusion of folk and rock and jazz. This was the breakthrough point.

Was there a particular song that did the trick?

“How D'You Do?" ("Owuro L’ojo"), the one that talks about the morning. I would say it's the most played song in this country. People will tell you about all the most popular hip-hop guys, but if you ask those guys what is your favorite morning song, they will tell you about this song. It's played on almost 60 percent of the stations in this country every morning. I don’t get royalties for that, but it’s fine. It just says, “Good morning. How do you do?” It mixes Yoruba and English. There are five or six tracks on that album people love. “Seven Lifes.” Young people love that one to death. “Seven lives, seven seas…Seven valleys, Seven hills. Over sea and over land over mountains in the world, I’ll be big and I’ll be strong. I’m an African boy.”

[embed][/embed]

On your most recent album, Iwa, you have two CDs, one in English and one in Yoruba.

That's the first time I've done that. Normally I would put everything together on the CD to make it as fluid as possible for the listener. But this time, I just thought we’ve got 10 songs in English and 11 songs in Yoruba. They won't fit on one CD. So we'll just put them on two CDs and send it out there and see what happens. I don't measure achievement in terms of money, but I thought it was great that this album made it to number three in the world music charts in Europe. I thought it was awesome that we were somehow able to get some DJs across Europe to play it. Even in Canada it went to number one last October. But in Nigeria, we haven't been getting much airplay. Maybe it's our fault that we haven't been giving money to the radio stations.

Why did you pick the name Beautiful Nubia?

I know it sounds kind of silly, but don't forget I was very young when I did this. Now I'm stuck with it. At that time, beautiful was about spiritual beauty. Something beyond hatred. That's what I wanted, to be a blessing to my society, a blessing to everyone around me. This is the height of beauty. So I called myself Beautiful. I thought this would be a challenge to me. When they call you Beautiful, I think, “I'm not beautiful enough. I have to keep getting better on that path to perfection.”

Nubia came in later. Many Africans cannot see beyond having been slaves or subjects. When you are part of a conquered people, it is difficult to understand why you are not inferior to the people who conquered you. I think any conquered nation in the world will tell you the same thing. No matter what your artists and philosophers say, it's hard to get past that.

So how do you write from that condition? Instead of lying to yourself and trying to find your way in the world blindfolded, I realized that many African youth can't see beyond that. It's an inferiority complex. But if you can learn to find points in history that people like us, people who are dark skinned like you, were important, maybe then you will find something to be proud of. Well, I thought, the Nubians were dark skinned people, but they were the leaders in their time. The Nubians then were the U.S. of the world.

The Japanese have their reference points. The Chinese have theirs. It's not about what they've done in modern times, but they can hold their heads up. Nubian history was thousands of years ago, but it's something that we can all be proud of: Yoruba, Igbo or whatever. Anthropologists and historians acknowledge that Nubia was a high culture, perhaps the highest in the world. So maybe if we can find that point, we can say, "O.K., people like us once led the world. We don't just have to be followers and consumers."

The problem we have here is that we’re just consumers. There is so much we could be doing. But people can't see beyond taking money and doing material things with it. There are so many children with talent and energy. I'm sure you've seen it. I'm sure you've met lots of youth. They have energy and creativity. What are they doing? We are not encouraging our youth, not telling them the right things. So if we can get better reference points, we can use to build people's minds when they're young, so that might help this country and the continent. Anyway, that’s what these two names were about.

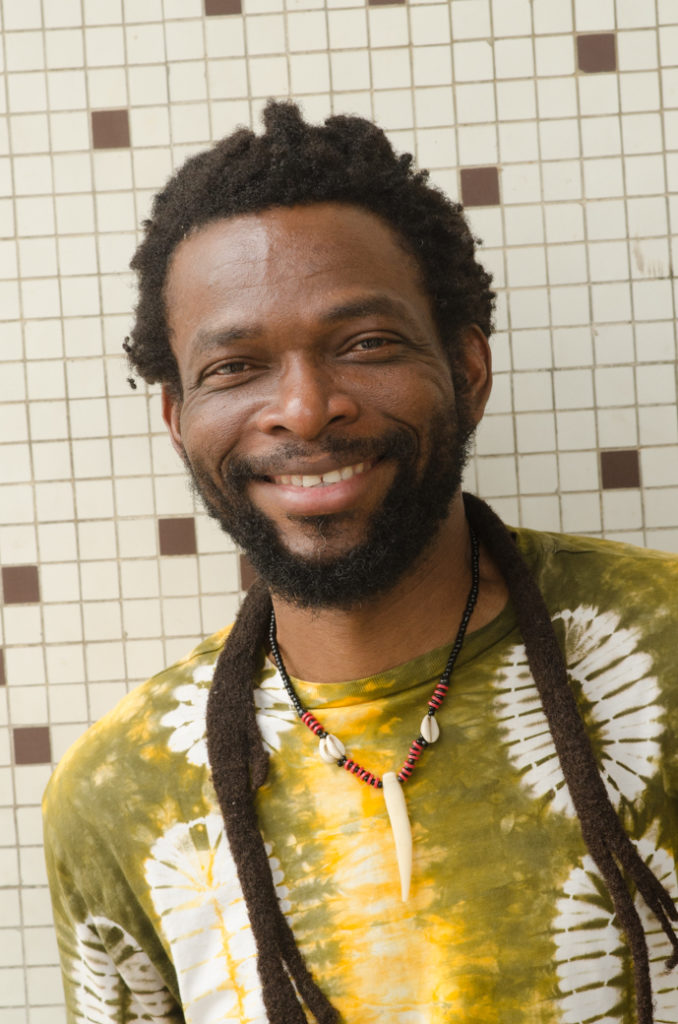

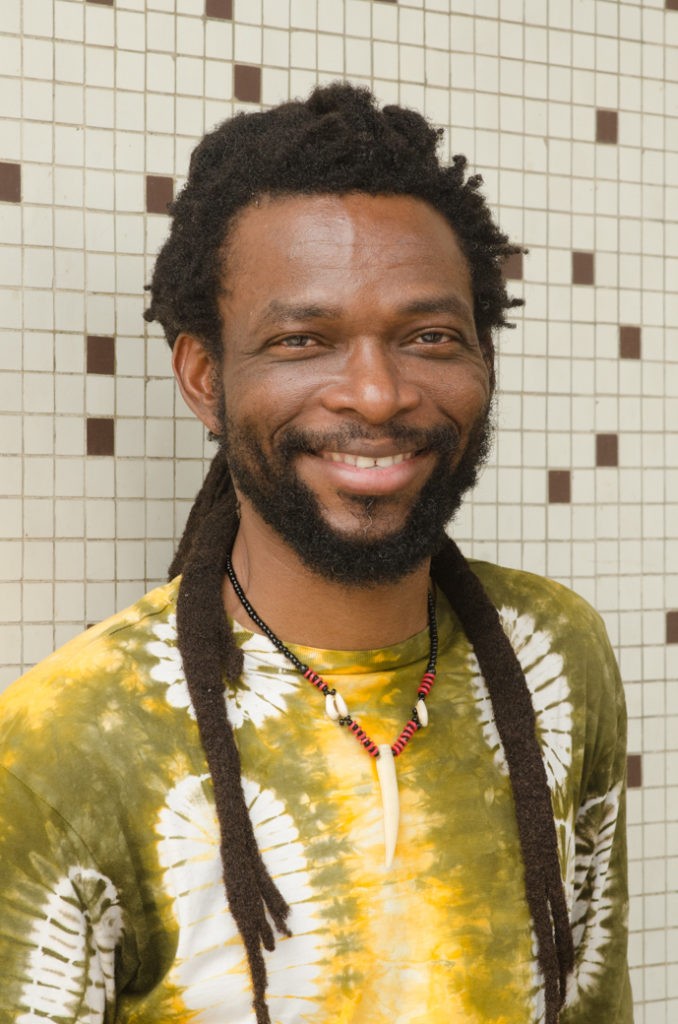

Beautiful Nubia and the Roots Resistance Band, live in Lagos. Photos by Banning Eyre

Beautiful Nubia and the Roots Resistance Band, live in Lagos. Photos by Banning Eyre

Today’s Naija pop might be the most successful African music that's ever been. People like Wizkid and Davido can go all over the world and find an audience. Huge concerts. And the language barrier doesn't seem to be a problem as it was in the past. But as many have pointed out, there's not much message in this music. We always hear that young people today know all about corruption and mismanagement, but…

…they just want to have fun.

Exactly. That's the refrain. What you think?

Well, it's the media. When I go on radio in Nigeria, I always tell them this. They like to ask me, "So, what you have to say to these kids who are listening to all this rotten stuff?" And I say, “I wouldn't come here and start criticizing them. People do what they think is going to serve them best. In 2002 when I did that album, this Afrobeats or Naija pop, whatever you want to call it now, was not there. The ones who started it, they are the ones taking money from these kids, and up till now, they are still taking money. It’s called payola. They take money from artists to play their music. No Naija pop music is played in Nigeria without people paying lots of money to media, to radio DJs, from morning till night, from one station to another.

When I was a kid growing up in Ibadan, there was balance on radio—you know local and foreign. My father loved his Jim Reeves, so we listened to Jim Reeves on radio. And when there was a flood, it was Bob Dylan forever. “How many roads must a man, blah, blah, blah.” They played it over and over and over. I can't forget it.

Then there was on the other side: traditional culture. They would go to shrines and broadcast real happenings at shrines. It was good. That balance was always there. Fast forward to now, and you can't even find a radio station with a 24-hour broadcast where it’s, "Next hour is reggae hour, next hour is soul hour, next hour is traditional music." No. You just start blasting this Afrobeats all day. A guy says, "I don't care if anybody has got anything. As long as I have food in my tummy, I am fine." This is the message you're sending out at 6 a.m. on a Monday morning? In a country that is in crisis?

I understand if your country is doing very well and you just want to have fun. Media is so powerful, but the media has not helped this country. They don't like to hear it. I tell them every time I go on the radio or TV stations. I always say it. And they tell me, “It’s survival. We need the money.” O.K., so then we can all just enjoy it, the bad roads, the lack of power, and the lack of good leadership. No. We can't all just sit here and enjoy it. If we want to see the change, then we have to start. Because it's the people who are going to change the system, not the American government or the British. We are always relying on those people. They are not going to come here and change it, it's the people who have to do it. But those people cannot change things if they have not got the right resources inside them. Music is such a powerful force, and people in this country love music.

You go to events sometimes, and they bring out an 8-year-old, a 12-year-old, little girls. Some of them just in their tattered underpants, and they start dancing, seductive dance steps. And I'm thinking someone is going to start abusing these kids. It all goes together, right? You start doing this, and then these little kids get raped at 8 or 10, or whatever, because this is the lifestyle you have exposed them to. They're not going to have that kind of early childhood, like the kind of childhood I had.

People sometimes tell me, "Oh, you sound so intelligent." Forget that! What is intelligence? I learned from the right people. We were exposed to the right things. We read the right books. Listened to the right music. But if you are exposing children to horrible stuff, low-quality stuff, low standards. What you put in is what you get out. Nigeria is a long, long way from becoming what the people want. I don't think many realize it. But if you build the people, you build the nation.

You blame the media. But I’ve also heard another view. In order to make money these days, artists need to get corporate sponsorships, government gigs, opportunities and money from effectively the most powerful people in Nigeria. So of course, you are not going to sing about bad roads and corruption and ethnical problems. It would be biting the hand that feeds you. Then other people say, no, it's not that. It's this thing about wanting to have fun. This is what young people want from music these days.

But I think it's also the nature of the music. People assume that if you play reggae, you're going to be protesting. And if you play this Afrobeats or hip-hop, it's going to be about jewelry and girls and parties. For this generation, it came from the American hip-hop, even though many of them don't know much about the early hip-hop that I knew, which was deep and serious. There was lot of poetry. But what they know is 50 Cent and these more recent ones with the big jewelry and the hoodies. This is what people think it’s all about. It's a culture unto itself, and that culture does not find talking about serious issues to be cool. It's not cool enough. What's cool is talking about how good you are in bed, how you took the girl and when she left, she was crying for days because you did this to her and you did that to her. This is what they sing about, having money to buy the Bentleys and Rolls-Royces. “My Rolls-Royce is rolling and it’s bouncing, bouncing to this rhythm. Would you like to come for a ride? It's bouncing. It's bouncing."

This is what people want to hear, and the media has created this monster. I always tell them: if you say one day, "We are going to create some balance. We’re also going to play music that is a bit more sensible, more educative,” then people will tend towards that too. But you know, I actually like these new songs. I am not against Afrobeats. If you are in a club and you’re drinking with people and having fun, they are fun songs. It's cool. It's club music, dance music. There's a place for it. But there's also a place for music that talks about issues.

Sometimes when I think about America, I can’t believe that the same country that gave us these great artists like Ray Charles and James Taylor and those kind of guys, has also given us.... I mean, I see the Billboard charts and the Grammy Awards and the people who are there. I don't want to mention names because some of them are icons to Nigerians. People love them. But I don't think they're doing anything that's really worth celebrating. My grandmother would tell me when I was a kid that everything in life goes in circles. Right? So maybe there is a cycle. It will pass, and hopefully when things turn around, music like mine will become popular. I hope so.

I understand what you're saying. We started covering African music in the 1980s when it was very different. It was Fela, King Sunny Ade, Miriam Makeba, Youssou N’Dour, Salif Keita, Baaba Maal, Thomas Mapfumo…

Oh, Mapfumo. Mapfumo is beautiful.

I actually wrote a book about him.

Yes. I read your book. That's why I know your name! I knew I'd seen that name. I’m a Mapfumo head. He is one of the artists I've always wanted to meet. Him and Burning Spear. I love those two guys.

That's excellent. Very nice to hear. Let me ask you a question about genre names. I gather that the people in the local industry here in Lagos want to call the new music “Naija pop.” But out in the rest of the world, they're calling it “Afrobeats.”

Afrobeats is a good marketing tool. But does it really mean anything? Fela called his music Afrobeat, and since he died, so many Afrobeat bands have sprung up all over the world. And they all do the same thing. The big horns. The messages. Yeah, it's nice, but it's a formula. Are you bringing something else to it? That's why you have to give Femi Kuti some praise. Not everybody loves what he does because they think he went too far away from the core Fela sound. But at least he tried to be different, something his own. Everybody else just sounds like Fela Kuti.

I don't know that I think part of the problem is that you have created a genre now, and people think this is how it is. Like roots reggae. This is how it sounds. And everybody has to do the same thing, and just lay down a few words, but it's the laziest way of making music. I can do 1,000 songs for you right now if you just give me that rhythm. This is what people do, and we are supposed to buy it and think it’s awesome. The same thing is happening now with Afrobeats. So this is the danger with labels. People start to think that if you want to do that genre, this is how you do it. But the fuji scene is different.

How so?

Well, the thing is you can listen to any of these fuji artists, and they are all different. But you really have to listen deeply. If you do, when you hear an Osupa song, you know it's Osupa. When you hear a Pasuma song you know it's Pasuma. When you hear Obesere, you know it’s Obesere. It's not just the voice. There's something about the way each one comes out. It's like when we used to listen to King Sunny Ade and Ebenezer Obey. They both called it juju music, but they were different. And Segun Adewale was different from them. And when Shina Peters started his Afro juju, it was different from them. That's what I like about them.

Fuji used to appeal to a particular section of the audience. In the beginning, it was the music of the Muslims. Then it started to branch out. Younger guys started coming in and introducing innovations. And they were not singing about Islam anymore. They were now singing about issues, and the tempo became a bit faster at some point. Now fuji artists have a lot of fans from across the country. Fuji also used to be the music of the poor. The more elite people listened to foreign music or juju music or highlife. The poor people listened to fuji. But I think it's gone beyond that. Fuji cuts across all classes now. It's still not the music of the elites. There are very few highly educated people who will say that their favorite music is fuji. They might say, sometimes I listen to that stuff. But it’s still more or less the music of the ghetto.

I don't think there's a fuji show you can go to where they won't fight. They always fight. Sometimes I am booked for the same show with a fuji artist, and people will be like, "Your shows are always peaceful. How are you going to do this?" And we just have to hope that the spirit that comes with us and envelops everything—that our spirit will be stronger than theirs. But there's no show I've ever had where there has ever been violence.

Why do they fight at fuji shows?

Well, it's all the stimulants that are there, the stuff that they drink and smoke. I think this is part of it. At my show, you drink palm wine. Palm wine doesn't make you violent. It makes you calm. But at these shows, they mix things up. They cannot drink whiskey straight. They have to add this, add that, and create like a cocktail. So at the smallest thing, they get angry. At their shows, it is expected that you're going to fight.

The only fuji you show I saw here in Lagos was at a fancy hotel. No one fought. And I've seen shows in New York. People didn’t fight there either, but they handed out a lot of money, so the fans can’t be that poor.

Well, the musicians themselves are not poor at all. They have a lot of money. And they do have their own clientele who have money as well. A lot of them are like business people, traders, or people who do other things I don't want to talk about. These are people who fund them. And I think that’s sometimes why they tend to fight. Because the fans expect the artist not just to play for them, but also to give them money. When my fans come to my show, they better pay to come in. Often at fuji shows, they will charge a very small amount of money to get in there. Sometimes the artist can't get in because the promoters want to extort from him. He can't play the venue until he pays them some money.

Last night after our gig, we attended a fuji show. It was Pasuma. We left our venue, we were going to our hotel, and just on the road there we saw people milling around. It was a Pasuma show.

Wow. I wish I had known. It seems like it’s hard to find out about these shows.

It is hard to find out about anything in Nigeria. We have talked about this for a long time. In 2004, my company tried to do a calendar of events that we could put online. “What's going on in Lagos this weekend.” Something like that. Well, we couldn't do it. We didn't have the funds. It was the early days of Internet stuff in Nigeria, and we couldn't find people to do it.

It is kind of amazing that no one has done that.

I've gone to like five of the key radio stations and said, "You are always taking money from us. You always think about making money, making money. But what have you done for the industry? Why is it difficult on a Friday afternoon to do a 30-minute program on what's going on in Lagos this weekend? Free advertisements for everything. People can just tell you there are events and you read them out. Then people know where to go.” Often people just stay in their homes. We think that Nigerians just like to be homebound. But they have to know where to go. There was one station that did it. I have to give them credit. They would list events every Thursday, Friday and Saturday, and we benefited from that.

[embed][/embed]

Let's talk about some of the songs in your new album, the double CD, Iwa.

The songs in English are about longing and romantic yearning. “Wrong Place, Wrong Time” is about a kid in trouble. But the Yoruba songs are different. The first one, “Sa Ma Jo,” is a call to dance. It just says you should just be dancing, even if it might not be a good time. That's kind of my Afrobeats number, but there's a message. I say there could be challenges. We have to face those challenges and be strong enough to overcome them, but just be sure you keep on dancing.

The second song, “Ase,” is a prayer. Prayer gets people. When they think it's a prayer, then you can actually inject a message that you want to pass across. So that song, I'm talking about how we can fix society. The one who decides to be a leader is the one who is honest, the one who actually loves his people, the one who has a plan. It says, "Who deserves to be the leader? It's the person who works hard.” We’re talking about the values of what a good leader should be.

“Mu’ra Ode” says, "Get dressed, darling. The rain is over now. Let's go out." In a lot of my songs, I try to embolden people, to inspire them. Too many people in this country are tired and depressed and despondent. I don't think many people can really understand the hopelessness that lower classes in this country feel. Very few artists even understand it. The people who live in this country are very unhappy. And the worst thing is to have a sense of hopelessness. I don't think it's fair to any human being that you are allowed to suffer like that. If it's of their own making, O.K. But you were born here by accident. It's an act of nature. And I think it is our duty to fix this so that those who are coming after us don't feel the same way. So in a lot of my songs I'm just trying to tell people you can't give in to that despondency. You have to try to do something. If you can make a little change in your environment, well, do it. In one of my songs, I say, "Even one good soul is a blessing to society.” (“One Good Soul,” from the 2015 CD Soundbender)

“Mo Wu Temi” is a song warning people not to go to quickly into things. You have to think before you jump. For me the most powerful track on Iwa is “Yeyeye.” But you have to be able to understand Yoruba to really get it. It is saying do not forget your good character. For the Yoruba, good character is the essence of human life. In Nigeria, the Yorubas are the ones in many of the most important positions. You'll see that the head person in Hausa or whatever, but Yorubas are actually the key people in this country. They are the ones who are good at corrupting everyone. They hang in there. They are the powerbrokers. They are everywhere.

But the essence of the Yoruba person, if you look at history, is the concept of iwa. That's the title of this album. If you ask a Yoruba person, "What is iwa?” They will say “behavior.” No, it's not. It's character, good character. That is the essence of a person. If your essence is bad, then nobody wants to deal with you. You are not worthy of being talked to, or talked about. It doesn’t matter if you have money, or faith, or whether you have achieved anything. It's whether you have good character. Every song on this first CD, the Yoruba one, talks about different aspects of good character, the concept of iwa.

Even a love song like “Abefe-Iwa.” Some guy is going to an old man to ask for the maiden. To ask for the girl's hand in marriage. But they are saying, "You want this girl because she is so virtuous. She's been well raised. She’s got all this character, this and that." That's the only romantic song on this album. Everything else talks about politics and social development and educating children, but it keeps going back to iwa as a concept that could help us develop.

Unfortunately, now, money has become the God of everything here. But to the Yorubas in the past, they didn't care if you were rich. If you didn't have good character, you were done. And I still see a lot of them. I have hope for this country because I don't think the majority of people are bad. I don't think the majority are corrupt. There are powerful elements who are very corrupt. There are people who you expect more from, who are not living up to their billing. I tell the people in this country that if we had good leadership, creative and visionary leadership, people who would lead by example, I'm sure we could do better. Because people want good times. They want someone who can make sacrifices and show them away. Then they will follow. But we have not gotten there yet.

Of course, it all comes from the way this country was cobbled together. That is our primary problem. But we can't keep talking about that as an impediment forever. You have to find a point where you decide that you really care about your people. I don't think the people who've been in government in this country care at all. But a new generation might come. In this country, I've played in the open air. I've played in primary schools, secondary schools, for no money. I do this all the time. I play open marketplaces. I just like to talk to people. Give me a chance to talk to one person so that I can pass this message on.

I don't know how long I'm going to live, but I want to be able to say that in my time I did the best I could. At least I tried to infuse some sense of order in our society, to get our people moving again. I'm not saying any country is perfect, but you see where people who are in government were it least responsive to the needs of the community. Maybe they were also self-serving, but they would try to do things to improve their environment. One government comes in and says, “This is how we think things should be. We’re going to do it this way.” Then another government comes and says they're going to cancel that and they want to do it this way now. But at least they have visions. They have an idea of what they want to do.

There is no government you can point to in this country that has ever really done anything for the people. There is no leader this country has ever had that has been worthy of that title. No matter how much the West likes them, no matter what they say, none of them has even been qualified to lead a village. That is the disaster of Nigeria. You have all these people who've been leaders, in the house of reps, senators, and all these overrated and overpopulated houses of power.

You certainly have a clear-eyed view of the failures of leadership here, but you haven't given up hope.

Oh, well, we must have hope, or else everything is lost. We cannot just give up totally. Then we might as well just dig holes and bury ourselves. But the hope I feel, for me, it's in the children. And that's why all my efforts are with the young people. I don't waste my time talking to the adults. The adults who listen to this new music, I don't know if they're going to change anything. Some of the most corrupt people in Nigeria are not even those politicians. They are the ones in all those ministries who do all the paperwork for the leaders, the ones whose children are going to school in the U.S. and Canada and Europe. I don't know how a civil servant is able to send his child abroad for school. How much are they making?

But I don't worry too much about the adults. They are already messed up. I focus on children. When you go to a school, and you talk to little children, all sorts, it’s beautiful! Their minds are grasping. They're looking for something, and you can tell. We do something called the National Schools Tour, like Bob Dylan had his Never Ending Tour. Mine is now the Never Ending Schools Tour. I will go to any school, either to talk, to sing solo, or with my band. We do all the universities and polytechnics and colleges, but we also do primary and secondary schools. And when we do any one of those shows, I come back feeling better, more hopeful. Because kids listen to you.

[embed][/embed]

It’s as if nobody is talking to them. Their churches and their religious places have failed them. I'm not a very religious person now. I don't do any religion. But as a child I went to church with my parents. The church at that time, the ‘60s and the ‘70s, was all fire and brimstone. It was about: “You have to do good or you're going to go to hell. You're going to die. You have to be good. You have to be virtuous. You have to be disciplined.” The church now is not like that. The church in Nigeria is about money. “You don't have to work. Jesus will just give you money.” This is the message that kids get at church. Now they go to school. The teachers are too befuddled by the problems they are facing every day. So where are you going to get your wisdom? And no one listens to the elders anymore. Where are the elders anyway?

And so people like me have to step into the shoes of those elders, the kind of elders I used to listen to growing up. If you want to have progress in this country, and you want to develop our people, then the African who would be a world leader must be a perfect amalgam of traditional wisdom and modern knowledge. That's my line. You must be a perfect amalgam of traditional wisdom and modern knowledge. And when it comes to traditional wisdom, these are the values Yorubas used to talk about all the time. And the Igbos have this too. Everybody has it in one way or another in their culture. Selflessness. Hard work.

In Nigeria now, there is a saying. Someone will greet me saying, "Ah, Baba Beautiful, well done." I will say thank you. And they will reply, "This year, may it be small work, big money." This is a prayer. I say, “No, no, no! I want money that is commensurate with the work I've done. I do not want small work.” This is a very stupid prayer. You want to work a little and make a lot of money? I always tell the kids: “Do not do that stupid small work, big money thing. No, no, no. If you work for one dollar, you get one dollar. This is how it's supposed to be.” If we could have a system like that, honoring hard work and perseverance, humility and patience. And the biggest, biggest one, is something you have to learn when you're young: contentment. You have to learn contentment. Recently, they found $9 million in somebody's house. You didn't hear about that?

No.

You been here for a month and you didn't hear that? This happened two weeks ago. I don't know how many Americans you can find with $9 million in their homes. Cash.

Who found it?

The EFCC, the Nigerian economic commission. They went to this guy’s house. He was a formal general of the oil company and they found nine point something million cash in his house. They showed the picture. And this person I bet would have 10 houses in Lagos—one there, one there, one there. And then he goes to London and buys 10 houses in the most expensive part. What is the problem? What are you looking for? I don't understand it. So I tell the children, “You have to learn contentment, to be happy with what you've got. Do the best you can do. Life is about the opportunities you get.”

Yorubas have a saying for that: "Where your head puts you is where you live." It doesn't mean you have to stay where you were born, and stay poor. It means that the circumstances around you have put you in this position. You were born in the lower class. You can aspire to do better than that. But if that's all you ever do in your life, make sure you do it with good character.

When I was a kid we used to say it would've been nice to be born in the royal family of England. We always thought that would be better. But then we found Hinduism or Buddhism, the religion that talks about previous lives. We would read all these books about reincarnation and say, “Maybe we did something bad in a previous life, and we were sent to this place—as a punishment.”

But to give into hopelessness would be the worst thing. So our hope is the children. I think to have a chance to talk to another human being and to have them listen to you is one of the greatest gifts. You know that old African proverb: "You are only a person because of other people"? I can speak in front of thousands of students at Ife or Ibadan, and they keep quiet and listen. When the show is over, I go back and think, “I've just done something amazing with my life.” For me, this is what it is. I'm happy to be on this road, and let's hope that in our time we will see change in this country.