This feature accompanies Afropop Worldwide's Hip Deep program, Lebanon 3: Beirut Today. Producer Banning Eyre conducted many interviews in Beirut in researching this program. What follows is a set of photographs (mostly Banning's), excerpts from those interviews, and links to websites and videos providing more on this unique and diverse musical city.

Radio Beirut

Radio Beirut (Eyre 2013)

Radio Beirut is a nightclub catering to alternative music--folk, rock, hip hop, and more. It's also a web radio station, streaming live performances and music by many local Beirut artists. Founder Jihad Samhat told us:

"Radio Beirut aims at becoming that kind of platform with a greater outreach, because we’re radio online, on the web. So the greater diaspora of Arab peoples, or Lebanese people in other parts of the world, can tune in and listen to what's going on in the underground scene. The scene is very diverse. It ranges from the classical Oriental to funk and punk. Monday nights are usually hip-hop residency nights. There's an open mic. It's also a workshop, you could say. A lot of the young and hungry hip-hop heads come out and try out their stuff live, and we give them that chance. We’re independent. We get no external funding."

Abeer Nehme

Abeer Nehme and Banning Eyre, backstage at the Beiteddine Festival

"The traditional music of Lebanon is based on the Syriac/Aramaic music. You know, the Aramaic language was the language of Jesus and, mainly, it is this religious music that has built this tradition that we have in Lebanon. Basically, it’s the music of the people. Of course, we took from the Arab world as well, and we took from other areas. We are affected and affecting also other countries. We take and we give. I am also an ethnomusicologist. Me and my husband have a documentary television series, Ethnofolia, that documents music traditions in, for example Armenia, Turkey, Spain, Iran and other countries. I think music is the best thing that ever happened to humanity. It’s the first creation of God, I think it was music." Abeer Nehme

Rima Kcheich

Rima Khcheich (publicity photo)

On working with jazz musicians: “It took time actually. At the beginning, I used to choose the songs that can be played on the saxophone, for example. On the bass, there’s no problem because it’s about taking time to get the quarter tones, and already he’s great. In the new album, you can hear that he is doing all the Arabic maqamat with all the quarter tones, but after like 14 years of working together. The double-bass has a different role in jazz than in classical Arabic music, because in classical Arabic music, the bass is there to pinpoint the rhythm, to play simple notes—it’s a different role, a different way of using the bass. So I did many tracks only as a duo with the bass, and now we do performances together, I mean whole concerts.”

On her new CD, Muwashahat: “The Muwasha is a poetic form and vocal form. Usually the form is AABA, so the A has the same melody and the B has a different melody. Usually muwashahat, mix spoken and classical Arabic. So this is one of the reasons why muwashahat, when they first appeared, were not very well respected from poets that used to write the classical Arabic qasida. As a vocal form, muwashahat are very important because you find all the complex Arabic rhythms there, like 14/4, 17/8, 24/4, 13, and 15. So today, if you want to teach musicians about Arabic music, you can rarely find any examples of these rhythms, except in muwashahat, because no one now uses these rhythms.”

On changing traditions: “You cannot close everything. You have to interact with the world around you and it’s not wrong. If you know your tradition well, you can try to do something new without ruining the tradition. I come from a very traditional background. So I know where my limits are. Some people are really ruining the tradition—they either don’t know the lyrics, or they change the maqam (modes). This I don’t agree with, but we can’t stop somewhere and say, “No, we will turn around.” This is I’m against, completely.” Rima Kcheich.

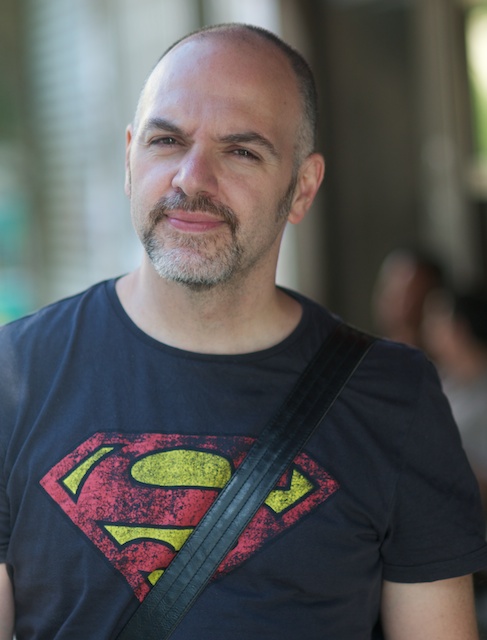

Mike Massy

Mike Massy (Amara photos)

“I am a Lebanese musician, composer, singer, pianist, and actor, and I try to do my best to make sure that what I do is something that pleases me. Since I released my album, they try to classify me: ‘You’re an alternative singer.’ My music is unusual, it’s out of the box. And of course, when it actually comes to these alternative musicians on the scene, they tell me, ‘You’re a bit commercial.’ I am inspired by rock music, and classical music, and all these things because of my long years of studies at the conservatory.”

On his experience of the Lebanese civil war in his hometown, Jounieh: “The war started there in 1990, and it was terrible. We had a very difficult childhood, always feeling not secure, waiting for my dad to come back, and we don’t know if he’s coming back or not because he is going to sell some food or something in his car far away in Beirut. At home, we used to listen to Aznavour and Brel and Dalida, Shirley Bassy, Frank Sinatra and these things. Then I said to myself, ‘I don’t want to add anything new on this kind of music unless if I go back to my roots.’ And that’s why I started listening to oriental music and trying to discover it, because I was not raised on this, except, of course, for Fairuz and Zaki Nassif. But with the war and all these things, they gave me the urge to go back and understand why all these things happened in this country. My relationship with Lebanon, with Beirut especially, is hate and love; it’s a passion thing. If you ask me “do you love Lebanon?” I don’t know, I really don’t. I hate it and I love it at the same time, and that’s very cruel and very violent. It’s not a healthy relationship but it makes its charm, unfortunately.” Mike Massy

Moe Hamzeh

Moe Hamzeh (Eyre 2013)

Moe is the leader of the Lebanese rock band, The Kordz. These days, he is working in media, helping to develop an online platform to market Lebanese cultural products worldwide.

On his childhood amid war in Beirut: “During the war there were so many radios, very good radios. And this is where I got all my musical knowledge. There were no licenses, official licenses, so anyone could open the radio and put the music. There used to be nice shows, classic rock, alternative, whatever. I personally used to listen to Pink Floyd at night. Usually at night, afternoon, onward, this is where the fighting starts. Bombs, shelling. You have to go down to the bunker and stay there. Sometimes there are buildings were they don't have basements, so people from other buildings, the used to come in. So it would be crowded, lack of oxygen, humidity, the smell. I still remember that smell. So I just listened to Pink Floyd at night, put my headphone and put the speakers loud. I don't want to listen to what's happening around me, like the bombs. I just kept dreaming. It was really like mental travel, just escape. And then, in the morning, I really wanted something sort of hopeful. So Bob Marley was for me something that gave me the power to say, I want to have my day. It gave me sort of happiness, and a smile, at the same time a way to fight for the future, and not just give up on what's happening. So that was the mix of my days and nights.”

On the rock scene after the war ended in 1990: “There was a case that changed the whole thing, a kid who committed suicide. It was just after Kurt Cobain's death. And then they tracked that the reason of his suicide was the music, although that was not the case. Then they went on to record stores to confiscate all these albums and CDs. There used to be a black lists of artists then. I worked for Virgin Megastore, so I had to face on a day-by-day basis all the issues of censorship. Even performing live, people were afraid. Yeah, because these to come to these parties, you know, when you have local bands performing metal, you never know when the secret police would come. Really it became something people were afraid to do. So this really created the need to have this subculture of rock.”

On today’s music and media business: “It's not easy to get a radio license. You really have to a lot of connections, business money. It has to have on the board people from all religions, all the sects: Muslims, Shiites, Sunni, Christians. All that so you can have that license. In Lebanon or even in the region, we don't have a proper music industry structure. I don't even call it an industry. There is music business going on, but we don't have the Ahmed Ertegan, the Seymour Stein or David Geffen of the Arab world. This is why I never called it an industry. You know, since they started all these televised ‘idol’ shows years ago, I can't recall one guy that really became a star, like someone big.”

Zeid Hamden

Zeid is credited with being a--for many, the--prime mover in establishing the underground music scene in Beirut. His bands include Lombrix, Soapkills, The New Government, Zeid and the Wings, and Zeid and Maii.

Zeid Hamden live at Radio Beirut (Eyre 2013)

On the civil war: “I lived my youth with the sound of air attacks. You know, in ’82 it was the Israeli Lebanon, very intense fighting between Palestinians and the Christian factions. Beirut was wrecked city, destroyed buildings, check points. The youth expressed in heavy metal because it was very aggressive, screaming, loud music, very violent music. That was the perfect style of music to just put your anger and express your youth. You know, every youth needs a place where they are just loud and violent, like killers and knights and warriors."

On his musical education: “I had good luck growing up in a family without religion. My father was Druze, my Mom was Orthodox; there was never questions of religion in my house. I grew up not understanding the reasons of war, because my parents were not affiliated. And when I came back later in 90s, I understood that religion had a big part in the fighting. And how I was affected was a lot of my music would address all communities, and a lot of my themes would be you know, forgetting those artificial boundaries between people. The main value is the love. My parents were very passionate about each other, very much in love. So I was educated in this principle, that when there is love, it’s the biggest shelter for wars and problems. When you are affiliated and you live in a war environment, extremism grows in your heart. I didn’t have that, I just grew knowing that two people who love each other protect each other, whatever the circumstances.”

On his early music: “I could not appreciate oriental music. And in my band, I would play exotic Arabic music, like the very naïve Arabic scale that you do on your guitar, and I would sing in English over it. But even then, people loved it, thinking it was like a new style of Arabic music. Then I replaced the band with this machine and started programming minimal electronics. Yasmine and I started doing Arabic music, because Yasmine had the culture that she had heard at home. She started singing to me the songs, and I adapted them on this machine. She would sing for me songs by Asmahan for example, ‘Ya Habibi Tahala.’ It was just acappella, and she was a very charismatic singer, and very beautiful. And then I would just program it in a Western way, because I did not understand Arabic music or the quarter tones at the time, and she didn’t sing quarter tones well. So journalists would hear new versions of the classics that they knew and, ‘Oh my god, they have built a bridge now between the Western music and the classical Arabic.’ We were creating the new Arabic music, which was Arabic electronica.”

Zeid and his Roland MC303 groovebox (Eyre 2013)

On the name of his signature band, Soapkills: “We were feeling that in Beirut, because the whole downtown was being wiped away, like cleaned up. All the remains of the war were being completely erased, and we felt this was being done without a real understanding of the reasons of the war. Soapkills didn’t explain all that I’m talking about, but it was a title that would make you somehow think about where we come from and why. This idea of looking clean but being really dirty, which I think until today applies so much.”

On the media reaction to Soapkills: “We were just wrecking the Arabic music, killing the quarter tones, taking off darbuka and the orchestra, alternative. A lot of radios we would go to would say, 'We cannot play you next to the Arabic pop. We can only play you after midnight.' Yasmine and I were very frustrated. So we developed our career just in underground pubs. But we were gaining audience very progressively, and we were gaining attention of the media outside. That’s why until today they say we initiated an underground music scene."

Charbel Haber

Charbel Haber (Eyre 2013)

“My name is Charbel Haber, I play with a band called Scrambled Eggs in Beirut. We have 10 albums out. Some of them are punk, post punk, with some ambient influence in them. Others are more free improv and collaborations with musicians from the Lebanese improv scene.”

On breaking into the scene: “We were faced with promoters that had no idea what we were doing. Really, really, they guys when they called us, they were expecting this kind of rock, blues band, and they end up with a punk band. So it created a lot of misunderstandings in the past. You have to keep in mind that this band was mainly a Beiruti phenomenon, it didn’t expand to the rest of the country. When you go to the suburbs you have a completely different scene. And there is no connection between what is happening in the suburbs and what is happening in the city. It’s a completely different world.”

Charbel Haber (Eyre 2013)

On Lebanon’s notoriously slow internet: If you open up the internet, you open up free-space and people can communicate more, and that’s a problem for the state. We like the image of being a liberal country but we’re not. We’re ruled by little tyrants, you know. Little, little tyrants, not a big dictator tyrant, no, little tyrants backed by the church and the mosques and backed by the religious class. There is no one source of authority that we can attack. It’s impossible.

On Beirut’s famed insistence on partying despite war: “We’re like every alcoholic around the world: when it gets hard, he gets a drink and gets smashed, you know, it’s not something special. But it’s done on the level of a country, a community of people, like a common… It’s like a herd movement, but a herd movement of alcoholics basically.”

On the scene now: “It’s much better than before. Now we have venues that accept the music. We grew up as musicians, we had friends who grew up who wanted to open places and promote, and they grew up knowing us, what we do. Now the people who promote us and manage the venues know us, know what we do, so it’s much better.”

Hamed Sinno

Hamed Sinno (Eyre 2013)

“I'm Hamed Sinno. I am a vocalist for Mashou Leila. I am 25. I spent my whole life here in Beirut. I'm half Lebanese, half Jordanian. I went to AUB (American University of Beirut). That's where I met the rest of the guys and started getting into music.We were all in the Department of Architecture and Design at AUB. A couple of people put up a flyer saying they wanted to start a music workshop for architecture students. It started out with 15 people and a few professors coming into this room at the University and just jamming a couple times a week. And then it filtered down to the seven of us. That's how the band started. Informally in 2008.”

“When we started making music, no one was really doing anything in Arabic for example. It hadn't been there for a couple years. Soap Kills had broken up, and everything was coming out was in English, and that was kind of what we were trying to respond to. On the first album, we were quite consciously trying to discuss certain issues. So ‘Fasateen,’ we were trying to deal with sectarianism and class differences, so we wrote a love song about it.’'Ubwa’ is about bombs. ‘Min al Taboor’ was about the general politics of the country. ‘Al Hajiz’ is about checkpoints. ‘Shemm El Yasmeen’ is about homosexuality. ‘Im Bim Billi’ is about marital abuse and domestic violence.”

“When we got invited to play the Baalbek Festival last summer (2012), we got trashed by all the media because they were saying we were too young, one. And two, the general playing card in criticizing our music was that our "ethics" were an issue—which, as far as I'm concerned, is disastrous. So than the bulk of the criticism that we were getting from the more popular reviews was about trying to decode the lyrics and pull up stuff that referred to gender or sexuality. And then it was always that this can corrupt the youth and we shouldn't be supporting it.”

“We tried to play outside Beirut once, I think in a concert where Charbel Haber was playing as well with a band called The New Government with Zeid, and a couple of other French guys who are incredible. So we're playing this Festival in like Zahle, and literally, the people that came, everyone left within the first 10 minutes. And the people that stayed only stayed because they were really angry. We got threatened on our way out. It was quite absurd. But yeah, you don't get the same kind of reactions once you get outside of Beirut.”

On their success throughout the region: “Stuff as small as a Facebook page or Twitter account has been so helpful. If you're going to Cairo, you don't live there, start a Facebook page get your music across, and then maybe you can go play there. There always has been openness in Tunisia. Tunis has always been a liberal place. At least it was before the conservatives took over so much power. They made abortion laws okay before for France did. People are open-minded. Woman can dress as they want. Men can do what they want. And their musical culture is quite elaborate. We played Dubai a couple of times, but it's always difficult getting there because you have to get past censorship. It's hell for the organizers, so they always second-guess bringing bands like us. You have to provide every lyric you are going to sing. And they have to approve it in advance. And you have to do it every time.”

Anthony Khoury (Adonis)

Anthony Khoury (Eyre 2013)

Anthony Khoury leads a young pop band called Adonis, very popular in Beirut, and with a growing reputation around the region.

“The way our band started is by doing covers and trying to re-create songs from local folklore. The whole notion of folklore here is a bit different than in the States or Europe. Nothing is really written. Materials are mostly from live concerts, so it's like when we get into the real classical Arabic music, like from the 20s, 30s, 40s, 60s with Umm Kulthum, or the 70s and 80s with the Rahbanis, it’s really like a huge sea in which you have to dive. And you really don't know what you're going to find. It's a whole adventure.”

“We don’t have this whole jargon of war that bands used to use before, even in the music, like Zeid Hamden, and Soapkills—you used to feel this sounds even that they would use in their songs were dubs of bombs, of news reports of death, injuries. What we do is somehow more detached from that, because we haven't lived it. I hope we don't live it again, seeing the situation now.”

“Mostly, the subjects of inspiration for the songs on our first album were the architecture of the city of Beirut. Because most of us are architecture students at AUB, and we made our first album when we were in university, so we were very affected by this whole idea of space. The songs attach memories and stories to the spaces they happened in. So the titles of the songs at our first CD. Like one says ‘Rooftops,” one says ‘Windows,’ one speaks of a garbage can. ‘Streetlights.’ That’s actually the title of the CD, Dawal wa Ladiah, which is streetlights in Arabic.”

“We don't mind progress and we don't mind having a strip of towers. But it's everywhere. There's really no control over it. It's not regulated. There are laws, but it happens that there's a lot of corruption. The people that work in investment are mostly people in the Parliament, or friends with people in the Parliament, so they create laws for themselves. They appropriate territory. They destroy houses overnight, and then say it was a storm. It's a very important cause for us. It has to do with the identity of our city, our history. So our first disc was like an homage to these old houses.”

El Rass

El Rass, or Mazen el Sayed (Eyre 2013)]

“My name is Mazen el Sayed. My stage name is Rass, meaning ‘the head.’ I make music that is generally known as rap in Arabic. I am also a journalist. I am 29 years old. I come from the town of Tripoli in the north of Lebanon. I have studied math and finance and economics in France. I worked in banking for a while before I quit. Not just a job, but the whole lifestyle, and came back to Lebanon. I consider myself immediately and directly implicated in the public issues of my immediate circle of public sphere. Meeting the society I live in. And that goes from the small circle of my town to the bigger circle of my country, to the bigger circle of the Arab world, into the bigger circle of the world.”

“To be very clear, I don't feel like I belong to this hip-hop culture. I don't specifically identify with the social milieu that created it in the States, although I identify with it as the voice of the oppressed, as the voice of the marginalized. I identify with it as knowledge. Imagine that quantum physics was something of a common knowledge for everyone in society. I think if people really knew the details of the historical context of Islam, or any other religion for that matter, I think it would radically change the behavior of the everyday man and woman in their everyday life.”

“I believe in the culture of resistance. I believe in the culture of standing up to what you believe in, avoiding compromise. I believe in the power of words, and the power of ideas, and the necessity of breaking the status quo of thought and social human practice in general for the sake of well-being of women and men.”

“My first experience with producing a musical sound was reciting the Koran as a child. I

always had a very special relationship with that book and the whole musical culture that was composed on the basis of this Koranic lyricism. There is this pre-Islamic saying that poetry is the assembly of Arabs. Poetry is the core memory of Arabs. Arabs traditionally haven't written prose. Even scientific writings came before writing prose as an act of literature. And before Mohammed, before the birth of Islam, there were these very canonic structures of poetry. The whole poem was always in one rhythmic structure. [RECITES] Mohammed came and he broke this form. He wrote this corpus that is liberated from this canonic, monotonous way of rhythm, but is not liberated from the whole concept of rhythm. There is always rhythm. [RECITES] This is flow. This is lyricism. And the whole Koran is like this, different rhythms and rhymes with some components of historical knowledge, [some components of] very abstract philosophical knowledge. So, basically, this act of lyricism with a rhythmic component, with a liberating component, with this knowledge diffusion and propagation component--all these characteristics are what defines the Koran as a text.”

“One track from the CD I made with Mumha was about Beirut. It's called ‘Borkan Beirut,’ meaning ‘the volcano of Beirut.’ I took the two main factions that control Lebanon politically--to talk generally, the pro-Iran camp and the pro-States and subliminally, pro-Israel camp--and I deconstructed them to show that they are really one side, and we are the other side. Let's say it like this -- I don't want to choose between dictatorship and occupation. I refuse this choice.”

"Even if you're going to be the victim of a witchhunt, at least you play your role in the constant evolution of your society, and stopping it from dying, from being a total victim of human colonialism. Because when you lose your link with yourself, this is where you become colonized."

Ahmed Khoujah (Khat Thaleth)

Ahmed Koujah (Eyre 2013)

“My name is Ahmed Khoujah, Dubsnacker, or El Munaqresh, he who snacks. My family is Syrian. Our heritage and we have family there. We spent a lot of time there. I was born in the States, but I grew up for the first third of my life in Kuwait. And then I spent most of my life back in the US after that. I've been in Lebanon living here for about three years now. I've been a drummer since I was a kid. There was a compromise to get me drumming lessons so I would stop beating on everything in the house. So after different stages of my life, I started to expand to be playing in different bands, to producing some music, to deejaying and coming back to drums in the form of djembe in West African percussion.”

“For me personally, and the artists that I’ve worked with, hip-hop is either our style or medium of choice. It's one that is very appropriate for this type of expression. It’s information, really. If you look at hip hop in general, even hip hop that tends to have a lighter meaning behind the lyrics, it's still information about how certain people are living, what's kind of relevant enough for them to talk about in their music. Hip-hop has definitely been the voice of people under pressure, who are living in dire situations, and connecting with ideas, their rights, and they're kind of share in society.”

On his 2013 compilation of Arab hip hop, Khat Thaleth: “Khat Thaleth means third track or third line. The idea behind that came out of conversations between me and El Rass, as well as other artists and friends. We started to feel especially after Syria, as well as Bahrain, to be honest, that things are really becoming polarized and divisive. People were understanding their perspective in a very binary, regional, geopolitical context. If their sect or their alliance is with this group over here, then that dictates what their position is going to be on this revolution or on the changes happening in this country. Really, we just started to see it is so counterproductive to the moment and the opportunity, so the idea behind Khat Thaleth was a third way or third track. Basically, it’s expressing an independence to how we develop and construct our thoughts.”

Raed el Khazen

Raed el Khazen (Eyre 2013)

Raed is a guitarist and producer who grew up in Beirut, but left to spend 13 years in Boston and New York. He returned to Beirut in 2009. He produced Mashrou Leila’s first CD, mixed and mastered the tracks on Khat Thaleth, and, recently, produced the debut CD for a Syrian rock band living in Beirut, Tanjaret Daghet (Pressure Pot). His first impression of music in the Arab world was not good, a product of “colonization.”

“That's what colonization is. You lose your sense of who you are and what contemporary means. So you are stuck in this vortex. And that's what's been Arabic pop. Like, you really want to sound like Beyoncé man? Beyoncé grooves her ass off, practices dancing six hours a day, puts on a show that you don't even dream about. Why are you selling us short? I look at the music scene in the Arab world -- now it's changing -- but I came back and I looked at the music scene in the Arab world. You have relics of the past, a silicon present, and all this contemporary free improvised music, and you have a bunch of musicians try to imitate the West, not in our language, not in our grooves, not in our melodies. Wow, that's pretty bad. That's really bad.|”

On Khat Thaleth: That was really done guerrilla style. But it's beautiful, it's raw. It's truly what hip-hop was. I found what hip-hop was in the 80s in the states here in Lebanon. Actually, I'm finding a lot of what the music scene was in the 50s, 60s, 70s, was 80s in America -- -- the frustrations, being fed up of a system that's oppressing you, that's dictating on you what to do, how to do it, why to do it. There's become an awareness through the Internet. People are reading. People are knowing. People are understanding macro politics better. It's not the politics of alleyways anymore. People are seeing the bigger picture. People are seeing what colonialism is. People understand the new Middle East that they are trying to create. People are not stupid anymore, and they need a voice.”

“The message that Khat Thalat was conceived under speaks for the whole Arab world. And it's the voice of a whole generation that was lost, a few generations that have been lost, including my generation. So I think there was an extra effort on everybody's behalf to really do a good job, and to really get out of the cliché. Then, the productions music wise have a lot of Oriental grooves and spacing and everything that helped the delivery also. I don't believe it came from elsewhere. That's what we decided to be. It's ancient. It's before Harlem. It's before the Bronx. It's before New York. It's just rhythm and words.”

“We are so enthralled by being Westerners. Kudos to whoever colonized us. Great. They did a great job. [LAUGHS] That type of empty social structure that always looks to the West as God is the only way they can ensure peace in the Levant. On a cultural level, once you normalize that Arab identity, peace will become easy. And Arab is not smoking a cigarette or beating your wife--because this is what they want you to think Arabic is--or having an open shirt with hair and in speaking loud and having a lot of temperament. That's not Arab. Arab is poetry, Arab is love, Arab is music, Arab is great culture, old culture. They want us to forget that part of Arab. And our alternative is the West. So you are either in Oriental fad, or your somebody wants to blow himself up. What I'm saying to these guys is, no, no, no, there is a third option: actually being Arab. Being generous, being non-chauvinistic, loving women. Change is coming, man. I tell you. Change is gonna come.”

Ziad Nawfal

Ziad Nawfal (Eyre 2013)

“I'm a Lebanese radio host and music producer, and concert promoter. Based in Beirut Lebanon. I started out as a DJ first. And I'm still a DJ and also had a radio program on the local government radio station called Radio Lebanon for 20 years or so. The night show is called Ruptures. The day show is Decollage, Ruptures in French. And my label has been running for four or five years is also called Ruptured. It aims at producing and releasing local alternative music. We did El Rass’s first CD, and a set of 5 compilations of recordings from the radio program.”

“You'll find that everyone has a disparaging opinion about everyone else. It’s a very small scene filled with very big fish. These musicians want to be recognized for what they are at all time s, so there's very little space for collaboration. They’re not very generous, or sympathetic to other bands. This is why this person will criticize this person and that artist would criticize this artist. At the end of the day, there's many people fighting for a very small parcel of land. And as soon as one of these people grabs the parcel, they run away with it.”

“I think there was a time, post 2006, where the wave of change, or the wind of change was supposed to come by way of alternative bands saying something about the actual political situation of the countries. Whether it's Scrambled Eggs or Mashrou Leila. Or the rappers or whatever. And Charbel's friends would tell him, ‘You should sing in Arabic.’ He would refuse. He would say, ‘My voice doesn’t sound good in Arabic.’ And Hamed, the singer from Mashrou Leila was requested to pen songs with more political content. He said, “I don't know about these things. I’m just an AUB grad. I don’t have an opinion.’ So I think there was a missed opportunity there.”

Finally, notes on three popular Lebanese singers, people with videos on satellite television. We did not interview them, but Khaled Racy (brother of ethnomusicologist A.J. Racy) told us about some of their songs, which he feels represents a new trend in Lebanese mega-pop: satirical and humorous songs that deal with social issues.

Mohamed Iskander

"There is a new class of songs that handle social issues, in a very modern way. It's not fake romantic things. No. Mohamed Iskandar is amazing. He's funny. He has a good voice. And there are songs here. One of them is “Joumhoureyet Alby.” It's about his daughter is asking that she wants to be educated. And he is struggling. Why should you go to school and be educated? Because I love you very much. And then if you go into education, then you get employed in a company. Then the manager of the company wants to flirt with you. And then of course I am going to kill him, because I will not accept these things. Very funny. Extremely interesting. And this was a hit."

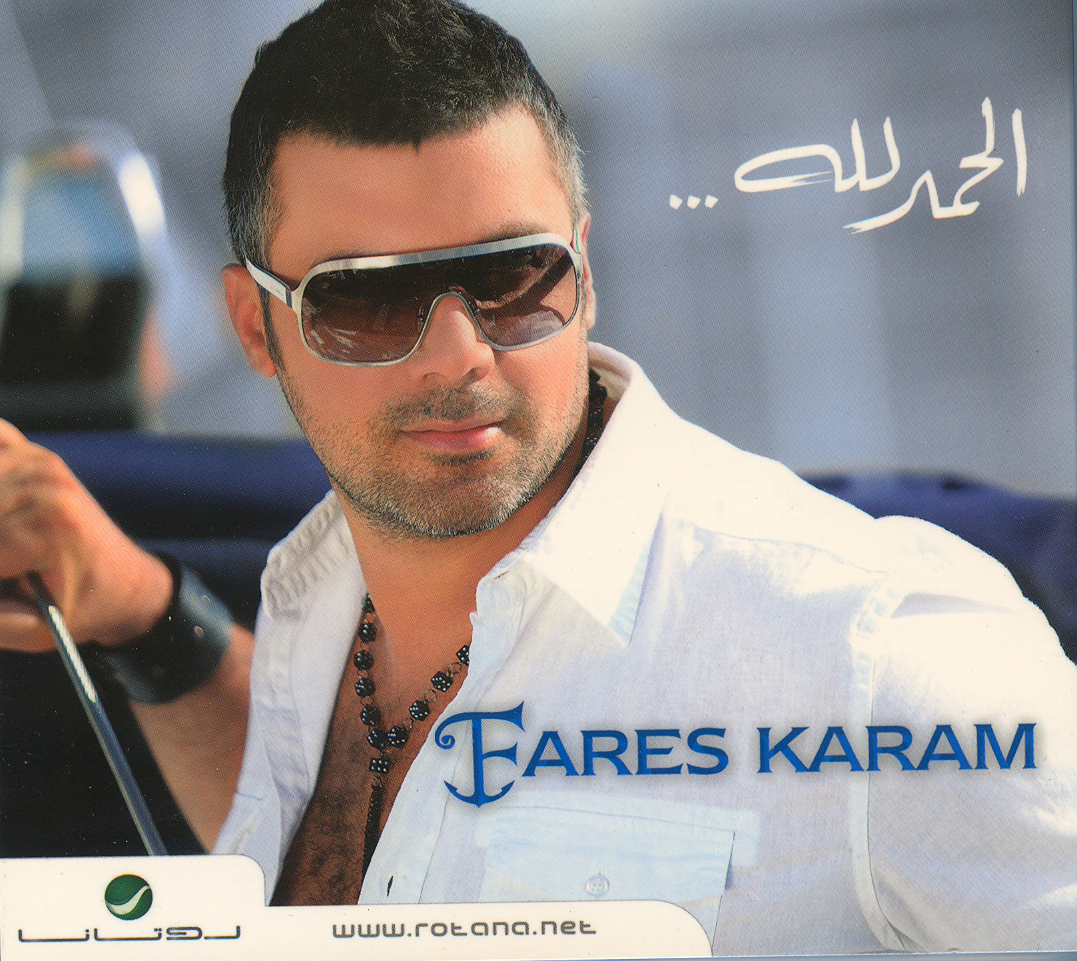

Fares Karam

"Faras Karam is a very good singer. His song "Ritanni” says, "I wish I were." The story is that he is in a village, and the Army has just confiscated a huge stock of marijuana or hashish, and they are burning it. And then the wind goes to that village, and he goes high. He starts seeing all the very old ladies in the village as supermodels in their beauty. At the end of it, the effect of hashish goes, and he sees his grandmother, and these old ladies making kibbe, and his grandmother or his aunt starts shouting at him, so he wakes up."

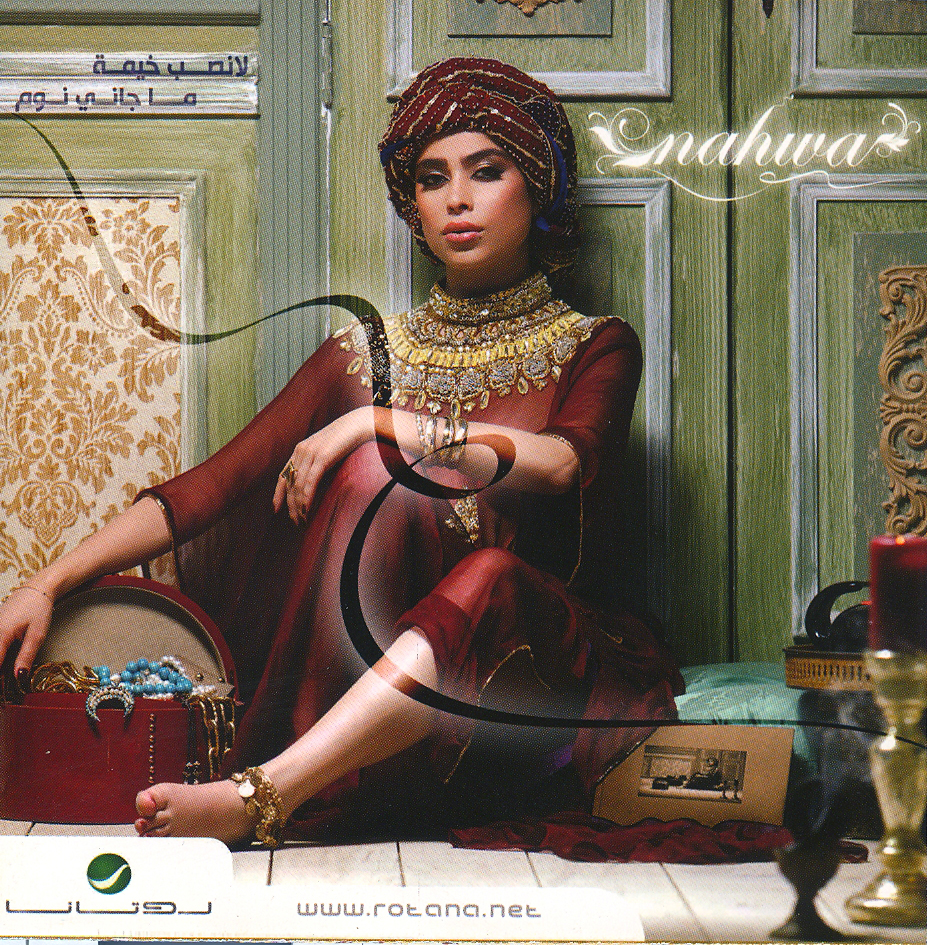

Nahwa

“Nahwa is a new singer. She started with two or three or four songs that were insignificant, until she produced two songs that in my opinion are terrific. She is from the Lebanese Bedouin. Now this is different from the Gulf music. The Lebanese Bedouin are the Bedouin from Bekaa Valley and the Syrian desert. Here in the 60s, we never knew that Bedouin were more than in Bekaa. They grind coffee. They play very well on the rababa. They play love songs to the desert, and there's the dabke, mainly from the Baalbek area into Syria. That's an extension.”

“The song ‘Lansob Khema’ means, ‘I want to erect a tent, far away from the city. I wish to erect a tent very far, near a spring, very far from the city.’ And then it turns into love…”