Blog June 20, 2013

Lebanon Journal 2: Ziad Rahbani

In Lebanon, the name Rahbani carries weight. Like Marsalis in New Orleans. Or Bach in 18th century Germany. The Rahbani family of composers established their iconic status in the second half of the 20th century, when brothers Mansour and Assi Rahbani teamed up with Fairuz, the greatest and most beloved Arab singer since Umm Kulthum. Together, this team merged Arab art music with Western classical music, popular dance music of the era—such as tango—and jazz. Using both high poetry and common street parlance, they addressed deep national sentiments, with particular potency during Lebanon's horrific 15 year war (1975-90). They created theatrical works that brought all these elements together and riveted the entire region. Excelling as composers, producers, popular figures, and promoters extraordinaire, the Rahbanis brothers left behind a legacy that can never be repeated.

They also left behind a handful of talented descendants bearing the golden family name, none more noteworthy than Ziad Rahbani, son of Assi and Fairuz herself. (At 78, Fairuz still records and, occasionally, performs, though she almost never grants interviews.) Kenneth Habib is a Fairuz biographer and a key adviser for Afropop's "Hip Deep in Lebanon" project, and he emphasizes Ziad's singular lineage. "He was surrounded by geniuses in really the truest sense of that word," says Habib "And they were working with geniuses. And, Ziad actually turned out to be a genius too."

[caption id="attachment_10646" align="aligncenter" width="582"] Ziad Rahbani (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

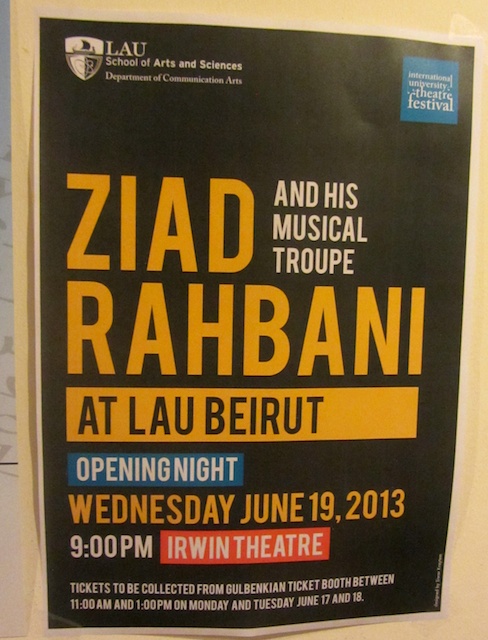

The concert I attended at Lebanese American University in Hamra--a short walk from my hotel--was an invitation only affair. Every seat was filled, and there was a strict ban on photography. Even the press was granted only 5 minutes, long enough for me to snap a few images, thought not to capture the full sweep of Ziad's 20-something-piece oriental jazz orchestra, fronted in various combinations by six vocalists, five of them striking women wearing matching red dresses--all with powerful voices. The music was a fascinating collage of big band jazz, sultry Arab vocals, semi-classical instrumentals, and theatrical interludes in which actors came on stage to play out provocative and sometimes funny scenes highlighting the social ironies of life in contemporary Beirut. Even without translation, I caught references to sectarian division, the Syrian crisis, and the unexpected hazards of jogging in Beirut.

Musically speaking, Ziad is a terrific jazz pianist, with a bold attack on the keyboard and fluid facility of genre from swing to bop to more ethereal oriental textures. A cover of "Hit the Road, Jack" bordered on kitsch. But a transforming take on "Autumn Leaves," a song Ziad famously arranged for Fairuz some years back, proved evocative and moving. A few other Fairuz songs interspersed in the 90-minute-plus program, consistently eliciting roars of approval from the crowd. And anytime an arrangements hinted at Lebanon's signature dabke rhythm--a potent cue to real or imagined memories of bucolic village life--the audience clapped along with gusto.

[caption id="attachment_10645" align="aligncenter" width="603"]

Ziad Rahbani (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

The concert I attended at Lebanese American University in Hamra--a short walk from my hotel--was an invitation only affair. Every seat was filled, and there was a strict ban on photography. Even the press was granted only 5 minutes, long enough for me to snap a few images, thought not to capture the full sweep of Ziad's 20-something-piece oriental jazz orchestra, fronted in various combinations by six vocalists, five of them striking women wearing matching red dresses--all with powerful voices. The music was a fascinating collage of big band jazz, sultry Arab vocals, semi-classical instrumentals, and theatrical interludes in which actors came on stage to play out provocative and sometimes funny scenes highlighting the social ironies of life in contemporary Beirut. Even without translation, I caught references to sectarian division, the Syrian crisis, and the unexpected hazards of jogging in Beirut.

Musically speaking, Ziad is a terrific jazz pianist, with a bold attack on the keyboard and fluid facility of genre from swing to bop to more ethereal oriental textures. A cover of "Hit the Road, Jack" bordered on kitsch. But a transforming take on "Autumn Leaves," a song Ziad famously arranged for Fairuz some years back, proved evocative and moving. A few other Fairuz songs interspersed in the 90-minute-plus program, consistently eliciting roars of approval from the crowd. And anytime an arrangements hinted at Lebanon's signature dabke rhythm--a potent cue to real or imagined memories of bucolic village life--the audience clapped along with gusto.

[caption id="attachment_10645" align="aligncenter" width="603"] Ziad Rahbani and musical troupe (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

During the second half of the program, Ziad became playful, amusing the audience with brief comments, delivered with the wry remove and expert timing of a seasoned comic. When a duet between Ziad and one of the singers was repeatedly interrupted by piercing feedback, he made light of it, switching from acoustic to electric piano, then back, stopping and starting, and ultimately abandoning the song without finishing it. The singer left the stage laughing, and Ziad moved on seamlessly. That near informality, and lack of concern for glitches beyond the artists' control, loaned the performance an air of untouchability. As singers, actors, and players came and went, and Ziad sprang up from his piano to vanish briefly, then reappear, or confer with the individual musicians, or--near the end--pull out his own camera to photograph members of the orchestra, the whole concert took on the air of a "happening," unlike anything I've seen before.

Watching this singularly entertaining performance, I had in my head the words of a brilliant Lebanese musicologist, Nidaa Abou Mrad, whom I had interviewed the day before at Université Antonine in Baabda. Baabda is an enclave of southern Beirut, and the university is perched high on a hill, with a spectacular view of the city and the sea, and a palpable sense of remove from earthly concerns. Antonine is a Catholic institution, and Dr. Abou Mrad one of its most esteemed cultural authorities. During our two-hour interview, conducted in French--which, along with a stack of books and articles and a thumb drive full of music performed by the Middle Eastern ensemble he directs and performs with on violin, will take me some months to digest--Dr. Abou Mrad offered a foundational explanation of this region's music.

[caption id="attachment_10642" align="aligncenter" width="605"]

Ziad Rahbani and musical troupe (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

During the second half of the program, Ziad became playful, amusing the audience with brief comments, delivered with the wry remove and expert timing of a seasoned comic. When a duet between Ziad and one of the singers was repeatedly interrupted by piercing feedback, he made light of it, switching from acoustic to electric piano, then back, stopping and starting, and ultimately abandoning the song without finishing it. The singer left the stage laughing, and Ziad moved on seamlessly. That near informality, and lack of concern for glitches beyond the artists' control, loaned the performance an air of untouchability. As singers, actors, and players came and went, and Ziad sprang up from his piano to vanish briefly, then reappear, or confer with the individual musicians, or--near the end--pull out his own camera to photograph members of the orchestra, the whole concert took on the air of a "happening," unlike anything I've seen before.

Watching this singularly entertaining performance, I had in my head the words of a brilliant Lebanese musicologist, Nidaa Abou Mrad, whom I had interviewed the day before at Université Antonine in Baabda. Baabda is an enclave of southern Beirut, and the university is perched high on a hill, with a spectacular view of the city and the sea, and a palpable sense of remove from earthly concerns. Antonine is a Catholic institution, and Dr. Abou Mrad one of its most esteemed cultural authorities. During our two-hour interview, conducted in French--which, along with a stack of books and articles and a thumb drive full of music performed by the Middle Eastern ensemble he directs and performs with on violin, will take me some months to digest--Dr. Abou Mrad offered a foundational explanation of this region's music.

[caption id="attachment_10642" align="aligncenter" width="605"] Dr. Nidaa Abou Mrad (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

For him, it all goes back to Abrahamic times. The same root that unites the Christian, Muslim and Jewish (Hebraic, was his word) faiths also unites many streams of music and literature, including the elaborate system of modes (maqamat) at the heart of Arabic art music. For Abou Mrad, this--and only this--is "tradition." And this tradition was badly interrupted during the Ottoman period, then revived in the late 19th century, especially in Egypt, during the Nahda, a kind of artistic renaissance in which "tradition" was gloriously reinvigorated by a variety of fresh inputs.

The trick is, for Abou Mrad and others, the Nahda period, over 100 years in the past now, was the true golden era of this region's music--and nothing since, not even the work of the Rahbani composers, has matched it. Actually, Abou Mrad went further than that. Watch this space for a transcription of our bracing conversation, which I will not attempt to summarize for fear of oversimplifying or distorting his subtle and beautifully formed argument. But I will offer this preview. Dr. Abou Mrad considers the influx of Western music, including notions of vertical harmony and diatonic scales, that swept through the Arabic-speaking world in the 20th century to be quite problematic. Fundamental aspects of European music do not derive from "the tradition" of this region, and cannot be reconciled with it, for demonstrable musicological reasons--nothing to do with culture or colonialism. So what has resulted, in Abou Mrad's memorable phrase, is "a patchwork."

Abou Mrad delivered this word with a twinkle in his eye, and, at the same time, utter seriousness. He did allow that Fairuz's Good Friday performances of Christian traditional music move him deeply, and that the Rahbani's were brilliant composers and "marketers." But sitting before Ziad's kaleidoscopic musical/theatrical circus at LAU, I sensed the distance between the music of the Nahda, which Abou Mrad's ensemble so vigorously preserves, and the "classics" of the Rahbani era, and Ziad's innovations or the pop formulations of Lebanese megastar singers like Nancy Ajram and Wael Kfoury--let alone Beirut's growing underground scene of rock bands, rappers, and experimental jazz musicians.

In that sweep of aesthetic perspectives, one begins to grasp the cultural complexity of Lebanon. And it serves as an apt metaphor for the country's spiritual and political complexities as well.

[caption id="attachment_10644" align="aligncenter" width="607"]

Dr. Nidaa Abou Mrad (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

For him, it all goes back to Abrahamic times. The same root that unites the Christian, Muslim and Jewish (Hebraic, was his word) faiths also unites many streams of music and literature, including the elaborate system of modes (maqamat) at the heart of Arabic art music. For Abou Mrad, this--and only this--is "tradition." And this tradition was badly interrupted during the Ottoman period, then revived in the late 19th century, especially in Egypt, during the Nahda, a kind of artistic renaissance in which "tradition" was gloriously reinvigorated by a variety of fresh inputs.

The trick is, for Abou Mrad and others, the Nahda period, over 100 years in the past now, was the true golden era of this region's music--and nothing since, not even the work of the Rahbani composers, has matched it. Actually, Abou Mrad went further than that. Watch this space for a transcription of our bracing conversation, which I will not attempt to summarize for fear of oversimplifying or distorting his subtle and beautifully formed argument. But I will offer this preview. Dr. Abou Mrad considers the influx of Western music, including notions of vertical harmony and diatonic scales, that swept through the Arabic-speaking world in the 20th century to be quite problematic. Fundamental aspects of European music do not derive from "the tradition" of this region, and cannot be reconciled with it, for demonstrable musicological reasons--nothing to do with culture or colonialism. So what has resulted, in Abou Mrad's memorable phrase, is "a patchwork."

Abou Mrad delivered this word with a twinkle in his eye, and, at the same time, utter seriousness. He did allow that Fairuz's Good Friday performances of Christian traditional music move him deeply, and that the Rahbani's were brilliant composers and "marketers." But sitting before Ziad's kaleidoscopic musical/theatrical circus at LAU, I sensed the distance between the music of the Nahda, which Abou Mrad's ensemble so vigorously preserves, and the "classics" of the Rahbani era, and Ziad's innovations or the pop formulations of Lebanese megastar singers like Nancy Ajram and Wael Kfoury--let alone Beirut's growing underground scene of rock bands, rappers, and experimental jazz musicians.

In that sweep of aesthetic perspectives, one begins to grasp the cultural complexity of Lebanon. And it serves as an apt metaphor for the country's spiritual and political complexities as well.

[caption id="attachment_10644" align="aligncenter" width="607"] Nidaa Abou Mrad, Banning Eyre[/caption]

Nidaa Abou Mrad, Banning Eyre[/caption]

Ziad Rahbani (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

The concert I attended at Lebanese American University in Hamra--a short walk from my hotel--was an invitation only affair. Every seat was filled, and there was a strict ban on photography. Even the press was granted only 5 minutes, long enough for me to snap a few images, thought not to capture the full sweep of Ziad's 20-something-piece oriental jazz orchestra, fronted in various combinations by six vocalists, five of them striking women wearing matching red dresses--all with powerful voices. The music was a fascinating collage of big band jazz, sultry Arab vocals, semi-classical instrumentals, and theatrical interludes in which actors came on stage to play out provocative and sometimes funny scenes highlighting the social ironies of life in contemporary Beirut. Even without translation, I caught references to sectarian division, the Syrian crisis, and the unexpected hazards of jogging in Beirut.

Musically speaking, Ziad is a terrific jazz pianist, with a bold attack on the keyboard and fluid facility of genre from swing to bop to more ethereal oriental textures. A cover of "Hit the Road, Jack" bordered on kitsch. But a transforming take on "Autumn Leaves," a song Ziad famously arranged for Fairuz some years back, proved evocative and moving. A few other Fairuz songs interspersed in the 90-minute-plus program, consistently eliciting roars of approval from the crowd. And anytime an arrangements hinted at Lebanon's signature dabke rhythm--a potent cue to real or imagined memories of bucolic village life--the audience clapped along with gusto.

[caption id="attachment_10645" align="aligncenter" width="603"]

Ziad Rahbani (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

The concert I attended at Lebanese American University in Hamra--a short walk from my hotel--was an invitation only affair. Every seat was filled, and there was a strict ban on photography. Even the press was granted only 5 minutes, long enough for me to snap a few images, thought not to capture the full sweep of Ziad's 20-something-piece oriental jazz orchestra, fronted in various combinations by six vocalists, five of them striking women wearing matching red dresses--all with powerful voices. The music was a fascinating collage of big band jazz, sultry Arab vocals, semi-classical instrumentals, and theatrical interludes in which actors came on stage to play out provocative and sometimes funny scenes highlighting the social ironies of life in contemporary Beirut. Even without translation, I caught references to sectarian division, the Syrian crisis, and the unexpected hazards of jogging in Beirut.

Musically speaking, Ziad is a terrific jazz pianist, with a bold attack on the keyboard and fluid facility of genre from swing to bop to more ethereal oriental textures. A cover of "Hit the Road, Jack" bordered on kitsch. But a transforming take on "Autumn Leaves," a song Ziad famously arranged for Fairuz some years back, proved evocative and moving. A few other Fairuz songs interspersed in the 90-minute-plus program, consistently eliciting roars of approval from the crowd. And anytime an arrangements hinted at Lebanon's signature dabke rhythm--a potent cue to real or imagined memories of bucolic village life--the audience clapped along with gusto.

[caption id="attachment_10645" align="aligncenter" width="603"] Ziad Rahbani and musical troupe (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

During the second half of the program, Ziad became playful, amusing the audience with brief comments, delivered with the wry remove and expert timing of a seasoned comic. When a duet between Ziad and one of the singers was repeatedly interrupted by piercing feedback, he made light of it, switching from acoustic to electric piano, then back, stopping and starting, and ultimately abandoning the song without finishing it. The singer left the stage laughing, and Ziad moved on seamlessly. That near informality, and lack of concern for glitches beyond the artists' control, loaned the performance an air of untouchability. As singers, actors, and players came and went, and Ziad sprang up from his piano to vanish briefly, then reappear, or confer with the individual musicians, or--near the end--pull out his own camera to photograph members of the orchestra, the whole concert took on the air of a "happening," unlike anything I've seen before.

Watching this singularly entertaining performance, I had in my head the words of a brilliant Lebanese musicologist, Nidaa Abou Mrad, whom I had interviewed the day before at Université Antonine in Baabda. Baabda is an enclave of southern Beirut, and the university is perched high on a hill, with a spectacular view of the city and the sea, and a palpable sense of remove from earthly concerns. Antonine is a Catholic institution, and Dr. Abou Mrad one of its most esteemed cultural authorities. During our two-hour interview, conducted in French--which, along with a stack of books and articles and a thumb drive full of music performed by the Middle Eastern ensemble he directs and performs with on violin, will take me some months to digest--Dr. Abou Mrad offered a foundational explanation of this region's music.

[caption id="attachment_10642" align="aligncenter" width="605"]

Ziad Rahbani and musical troupe (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

During the second half of the program, Ziad became playful, amusing the audience with brief comments, delivered with the wry remove and expert timing of a seasoned comic. When a duet between Ziad and one of the singers was repeatedly interrupted by piercing feedback, he made light of it, switching from acoustic to electric piano, then back, stopping and starting, and ultimately abandoning the song without finishing it. The singer left the stage laughing, and Ziad moved on seamlessly. That near informality, and lack of concern for glitches beyond the artists' control, loaned the performance an air of untouchability. As singers, actors, and players came and went, and Ziad sprang up from his piano to vanish briefly, then reappear, or confer with the individual musicians, or--near the end--pull out his own camera to photograph members of the orchestra, the whole concert took on the air of a "happening," unlike anything I've seen before.

Watching this singularly entertaining performance, I had in my head the words of a brilliant Lebanese musicologist, Nidaa Abou Mrad, whom I had interviewed the day before at Université Antonine in Baabda. Baabda is an enclave of southern Beirut, and the university is perched high on a hill, with a spectacular view of the city and the sea, and a palpable sense of remove from earthly concerns. Antonine is a Catholic institution, and Dr. Abou Mrad one of its most esteemed cultural authorities. During our two-hour interview, conducted in French--which, along with a stack of books and articles and a thumb drive full of music performed by the Middle Eastern ensemble he directs and performs with on violin, will take me some months to digest--Dr. Abou Mrad offered a foundational explanation of this region's music.

[caption id="attachment_10642" align="aligncenter" width="605"] Dr. Nidaa Abou Mrad (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

For him, it all goes back to Abrahamic times. The same root that unites the Christian, Muslim and Jewish (Hebraic, was his word) faiths also unites many streams of music and literature, including the elaborate system of modes (maqamat) at the heart of Arabic art music. For Abou Mrad, this--and only this--is "tradition." And this tradition was badly interrupted during the Ottoman period, then revived in the late 19th century, especially in Egypt, during the Nahda, a kind of artistic renaissance in which "tradition" was gloriously reinvigorated by a variety of fresh inputs.

The trick is, for Abou Mrad and others, the Nahda period, over 100 years in the past now, was the true golden era of this region's music--and nothing since, not even the work of the Rahbani composers, has matched it. Actually, Abou Mrad went further than that. Watch this space for a transcription of our bracing conversation, which I will not attempt to summarize for fear of oversimplifying or distorting his subtle and beautifully formed argument. But I will offer this preview. Dr. Abou Mrad considers the influx of Western music, including notions of vertical harmony and diatonic scales, that swept through the Arabic-speaking world in the 20th century to be quite problematic. Fundamental aspects of European music do not derive from "the tradition" of this region, and cannot be reconciled with it, for demonstrable musicological reasons--nothing to do with culture or colonialism. So what has resulted, in Abou Mrad's memorable phrase, is "a patchwork."

Abou Mrad delivered this word with a twinkle in his eye, and, at the same time, utter seriousness. He did allow that Fairuz's Good Friday performances of Christian traditional music move him deeply, and that the Rahbani's were brilliant composers and "marketers." But sitting before Ziad's kaleidoscopic musical/theatrical circus at LAU, I sensed the distance between the music of the Nahda, which Abou Mrad's ensemble so vigorously preserves, and the "classics" of the Rahbani era, and Ziad's innovations or the pop formulations of Lebanese megastar singers like Nancy Ajram and Wael Kfoury--let alone Beirut's growing underground scene of rock bands, rappers, and experimental jazz musicians.

In that sweep of aesthetic perspectives, one begins to grasp the cultural complexity of Lebanon. And it serves as an apt metaphor for the country's spiritual and political complexities as well.

[caption id="attachment_10644" align="aligncenter" width="607"]

Dr. Nidaa Abou Mrad (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

For him, it all goes back to Abrahamic times. The same root that unites the Christian, Muslim and Jewish (Hebraic, was his word) faiths also unites many streams of music and literature, including the elaborate system of modes (maqamat) at the heart of Arabic art music. For Abou Mrad, this--and only this--is "tradition." And this tradition was badly interrupted during the Ottoman period, then revived in the late 19th century, especially in Egypt, during the Nahda, a kind of artistic renaissance in which "tradition" was gloriously reinvigorated by a variety of fresh inputs.

The trick is, for Abou Mrad and others, the Nahda period, over 100 years in the past now, was the true golden era of this region's music--and nothing since, not even the work of the Rahbani composers, has matched it. Actually, Abou Mrad went further than that. Watch this space for a transcription of our bracing conversation, which I will not attempt to summarize for fear of oversimplifying or distorting his subtle and beautifully formed argument. But I will offer this preview. Dr. Abou Mrad considers the influx of Western music, including notions of vertical harmony and diatonic scales, that swept through the Arabic-speaking world in the 20th century to be quite problematic. Fundamental aspects of European music do not derive from "the tradition" of this region, and cannot be reconciled with it, for demonstrable musicological reasons--nothing to do with culture or colonialism. So what has resulted, in Abou Mrad's memorable phrase, is "a patchwork."

Abou Mrad delivered this word with a twinkle in his eye, and, at the same time, utter seriousness. He did allow that Fairuz's Good Friday performances of Christian traditional music move him deeply, and that the Rahbani's were brilliant composers and "marketers." But sitting before Ziad's kaleidoscopic musical/theatrical circus at LAU, I sensed the distance between the music of the Nahda, which Abou Mrad's ensemble so vigorously preserves, and the "classics" of the Rahbani era, and Ziad's innovations or the pop formulations of Lebanese megastar singers like Nancy Ajram and Wael Kfoury--let alone Beirut's growing underground scene of rock bands, rappers, and experimental jazz musicians.

In that sweep of aesthetic perspectives, one begins to grasp the cultural complexity of Lebanon. And it serves as an apt metaphor for the country's spiritual and political complexities as well.

[caption id="attachment_10644" align="aligncenter" width="607"] Nidaa Abou Mrad, Banning Eyre[/caption]

Nidaa Abou Mrad, Banning Eyre[/caption]