In the spring of 2005, Afropop’s Banning Eyre had the privilege of traveling to Bamako, Mali, to assist banjo virtuoso Béla Fleck and his recording/filming team in arranging meetings and sessions with some of that city’s greatest musicians. This was part of Fleck’s Throw Down Your Heart project, a documentary film shot in four African countries, and a pair of Grammy-winning CDs. This spring, the complete package is getting a deluxe reissue, and there’s a new addition: a live concert recording of Fleck with Malian kora master Toumani Diabate called The Ripple Effect. As the coronavirus lockdown got underway in March, Eyre reached Fleck by Skype in his home in Nashville to talk about the project. Here’s their conversation.

How is quarantine treating you?

Pretty good, actually. I don't want to be insensitive while people are suffering and dying, but it’s kind of great to be here with my family. I'm working on mixing an album, so I've got something to keep me from going crazy.

I remember meeting your son the last time I saw you perform. How's he doing?

He's great. He's more of a golfer now.

A golfer?

Yes. He's a freak golfer. He's amazing. But last night he and I watched Throw Down Your Heart. I hadn't seen in a long time, and he had only seen it when he was maybe four years old, so it was his first time really getting it. He got really excited about it. He loved it, so that was fun.

It holds up very well.

Yeah, though it looks funkier than I remembered with the cameras we had back then. It really has an old-fashioned look. It feels a bit like a home movie more than a highly produced item. But that's endearing.

It’s a sweet film, and I find it hard to believe how long ago all that happened. Fifteen years.

I get my dates off, because by the time it came out it was a couple years later. There was a lot of editing and we waited for the right time to release. And then there were the tours, so I have a lot of dates in my head.

Speaking of the banjo and Africa, I recently read Laurent Dubois's book [The Banjo: America's African Instrument] about the banjo. Amazing book.

Yes. That's quite recent isn’t it?

Right. 2016. A great read. And now you are going back to all this Africa material. How did that come about?

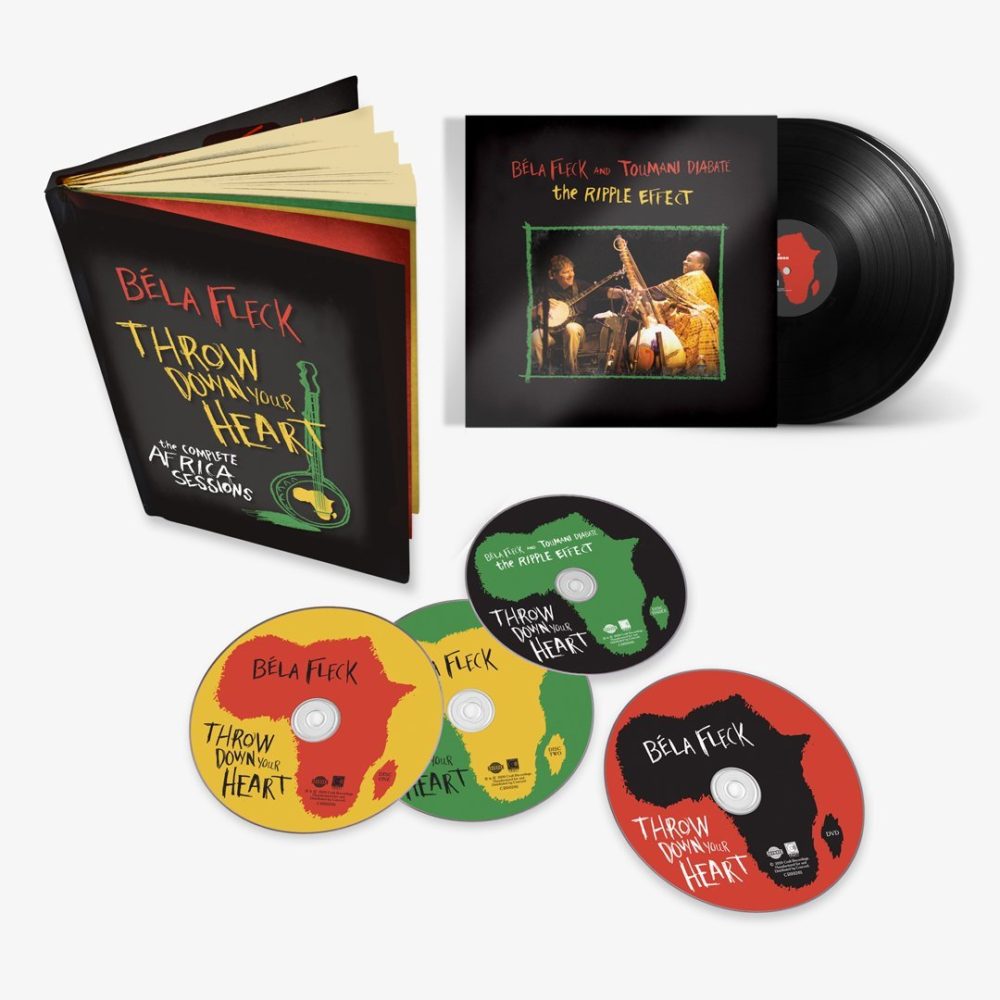

Really, what happened is we made some smart deals with the video company and the record company where we retained ownership. So 10 years after release, it sort of fell back in my lap, which is partly wonderful, and partly a huge responsibility. The wonderful thing is that some company doesn't own it forever; it comes back to my family. The hard part is we have to figure out how to responsibly keep it out there. When the deal ended, you couldn't hear the record anymore or see the movie anymore, so we had to find a way to get it all out. It wasn’t just a simple as making it available online. So we spoke to Craft at Concord and they showed a real interest. They like to do these VSOP packages where they find the uber-fan and sell them a $300 version of a record, and then if they sell 1,000 of them, they're happy. But that doesn't really make me happy, although it's lovely to have one of those around to look at and show my friends.

I like the idea of all the material being in one place so people can find it, but I don't like the idea that people can only see the movie if they're willing to pay that premium price. Or they can only hear the record if they're willing to buy three CDs and two DVDs worth of material. That doesn't seem right, and that doesn't seem helpful in the long run for the life of the project. To me it makes sense to make pieces of it available and let people go after the other stuff if they love it. So we worked out a deal where both these things could happen. People who already have it and want to go to the next level can do that. Maybe they saw the movie a while back but they never listened to the album. Maybe they never saw the extra footage, because you could only see that if you bought the DVD from this one company that had it for 10 years.

Actually, very few people bought it that way. Most of them bought it at shows where we were selling the DVD with just the original film. By the way, that was a great way to recoup some of the money from the trip, which was incredibly expensive. Being able to sell those DVDs was wonderful. It got a lot of them out to people's hands and chipped away at the huge investment I had made in this project.

But the other thing is that Toumani and I finally got together after the project, after the film, after the record. He overdubbed on a couple of tracks for the album. But as you remember, he was just getting home on the day we were leaving Mali.

I do remember that.

It was: Toumani's back! But, no, we had to get everybody on the plane and go home. Then I ran into him at a festival and I got to play with him. We jammed, and all of a sudden it seemed clear to me that this was a missing piece in the Mali segment. Not having him was a real loss. And so we started playing some duet shows. I think we played between 30 and 60 shows.

I saw one of those shows at Central Park SummerStage in 2011.

Yes. That was fairly early on. But generally we played intimate venues, smaller theaters and even a couple of jazz clubs. One jazz club we played was out in Seattle. We had four shows, two shows a night. And my soundman came up and said, “They have recording gear here. If you want I can press a button and record the shows.” And I said, “Well, absolutely. Four sets in the same room means four chances at the same material.”

You know what happens in the jazz club. The first set you play it like you play it. The second set to start looking for new things to do. The third set, you try to take it up from there. And by the fourth night, you're really trying a lot of stuff. That's why you want to go see a jazz group on their late-night set on the last night of the residency, because they're on fire. They haven't had to travel. The gear is set up. They haven't had to sound check. They’re loose and really familiar with the material. So that's kind of what happened here. I had four shows to pick from and lots of great versions of things. I feel like in certain ways it was the best we ever played, and the sound matched, so it wasn't like I was going to grab a song from this show in that show.

I'm a picky f***. That's both a failing and a strength. I'm always managing that in-between, being super picky and letting things just happen. Maybe you don't get that so often that one person where you can both be so picky, but also really into freely improvising and being loose. So again, it's a strength and weakness, but it's all there.

Anyway, we had this marvelous experience playing together. He was such a great, supportive player. So elegant. He made me feel like I could do anything, the way he supported me. And of course he soloed like crazy when he would. He would wait, and wait, and then all of a sudden, there it would be. So as the guy who got to curate the four shows, I was able to make sure I had it where he was really burning too.

Because Toumani's very self-effacing in a certain way. He would be very reverential, which was sweet, but I wanted him to bring it on. But generally, I think we have this very beautiful and comfortable way of playing together. When I heard it back again, I marveled at how natural and comfortable and free it was. I noticed that I played a lot of things that I might not typically play because of the way he played.

That's fascinating. So would you say most of the material you used comes from that fourth night?

I don't remember anymore. One of the nights got cut off because the recording stopped. I just laid them all next to each other and picked the best stuff. But I have a sense that some things, probably like "Dueling Banjos," was on the fourth night where we were just completely silly. We were punch drunk at that point. I would say that a good deal of it does come from that fourth night.

I can't wait to hear it. So far, all I've heard is the track that goes with the first video.

So going back to the release, there will be this deluxe package, but will it also be possible to go on YouTube or iTunes and hear the music and see the film?

What we ended up was that the individual pieces of the thing can be bought separately, including The Ripple Effect. And you get that in vinyl as well. They are beautiful packages.

No doubt. I've paid some attention to your ongoing adventures since that Africa project. You've done so many things. How do you look back on that experience all these years later?

It was one of the great experiences of my life. There is before and after Africa for me. I think were so many things that made it really special. I always tell people that if they want to learn to play a certain music, they need to immerse themselves in it, and so there were all these separate immersion processes. The first was studying the music from afar, listening to recordings for months and months before going. And then there was going, which was actually the shortest of the experiences, just five weeks. And then there was the process of editing everything we had recorded and filmed and making the choices. In the process of doing that, I learned a lot about the music and about what I did that did and didn't work. And then the last phase was the touring where, not only did I get to play music that I was familiar with, I got to play it every night for a month, on several different tours. And then finally, with Toumani, we pulled together a set and played it over and over again. That's how you get better at stuff.

People love to hear about you doing something off-the-cuff that you just did once. And that works great with improvising sometimes, but how about a chance to play some hard music that's not integral to your experience, and to do it over and over and over again? Then you start to make some progress. So for me, it was kind of like a five-year immersion period.

Do you think it changed you as a musician?

Well, at the end of that, when you're an improvising musician, it's very hard to point to what has changed. People will say, "Hey, play me some of that African stuff." And I say, "Well, how can I do that? It has to be in context with the other musicians." But in the big gumbo pot of whatever Béla Fleck is, it's in there, in unequal doses. Every time you pull out a spoon of whatever I am, some bit of it comes out, and there's more of this and more of that.

Sometimes something very African pops out when I'm playing with the Flecktones, or a bluegrass project, or Chick Corea. And sometimes something very bluegrass or jazzy pops out when I'm playing with African guys. So it's a big stew, and I think that's really what we’re all trying to be. I'm not trying to be a particular thing. I'm just trying to allow things to coalesce and develop and come into some kind of personal form of expression. I always tell students that that's the way to win: to figure out how to be yourself, not to try to imitate something or be something that you're not. So I let it flavor my experience, and it was a huge influx of new information, and also confidence. It was an incredible trip.

Do you still get occasional opportunities to play with African musicians?

Not much. I have played with the balafon player named Balla Kouyate, who has played with the Silk Road. Do you know him?

I know him well. He's fantastic.

Yeah. A great guy. He's kind of a family friend now. But generally, no. I'm on to other stuff. In some ways, I feel like the Throw Down Your Heart project still had a lot of life left in it when we finished. But like I do, I had another set of things coming immediately after it. I had a year off from the Flecktones, and that gave me the chance to do all that. Then I ended up touring with Stanley Clarke and Jean-Luc Ponty, and then doing the African tour simultaneously, and then on to other things, one thing after another. Chick Corea. The Flecktones. My calendar was full.

And to be honest, there were some nerves about bringing over African musicians. I wanted to play with the great people that I so admired like Bassekou [Kouyate] and Oumou [Sangare] and Toumani, but there was starting to be some trouble bringing people over. It was always touch and go organizing those tours.

I understand, and it's tougher than ever now.

So if I say I'm coming with a great African artist and then it’s just me, then what do I do? So just in terms of nerves, and also I’ve been moving into my family scene. People say, "Are you going back to Africa?" Well, I'd love to come, but right now it's more important to be part of my family and I don't go off on wild expeditions. Also a lot of the places we went have become quite dangerous.

Sadly, that's true. It was a particularly good time to go to Mali. That was the last time I went that it was the way I remembered it from the past. I've been back a few times, including just last year. It's still a magical place, but more tense. And you can't travel far from the capital. Also, the economies been failing in part because of the death of the tourist industry. It was a hopeful moment when we were there 2005. We were lucky.

What a shame. What a shame. But this project is a great snapshot of a great time, a great period, a great gang of musicians. You know, in music you have these great teams in different countries, The Wrecking Crew or the A-Team in Nashville. That was the A-Team we had and Mali for sure. You always have new guys coming up and there will be a new A-Team in 30 years.

It's true. But those guys are still there for the most part. I spent some nice time with Bassekou last summer. You mentioned your family. The last time I saw you was when you were touring with your wife, Abby Washburne, and you had your young son along. Seem like that was a nice way to have it both ways, the family and the music.

Yes. It was really nice for a number of years. But now we have a second son. He's going to be two in early June. He's walking and starting to talk. And boy, he loves the banjo. So it's a little bit more awkward now than it was, but maybe it will get easier. Of course now, everything's in flux as we wait to see how everything lands with this virus. We've had to cancel a lot of shows. We're just living at home. But as I say, I'm appreciating this time, and if something happens to any of us, I would be glad we had this time. All that, while respecting the hell that some people are in. We have to take this really seriously.

You mentioned cancellations. Oumou Sangare was supposed to play at the Apollo this month. It would've been her first time here in many years. And of course, we've lost some great musicians, including Manu Dibango. It's a crazy, chaotic time. But I know what you mean about appreciating time at home. We have most of the Afropop archive here in this house And we're slowly digitizing it. A long process.

How is Mali for the virus? So far so good, but I think they’re just beginning to really contend with it, and it’s a worry, with so little infrastructure and people living at such close quarters. There is a theory that in countries that dealt with the Ebola scare, people are more well informed about how to prevent spread. I hope it's enough. But it's a real worry.

I saw a map of Africa with just a few red spots on it.

Let's hope it stays that way. In the meantime, I'm so glad you're giving this project another life. It's fantastic music and a great film. And I'm really looking forward to hearing you and Toumani on The Ripple Effect.

Thanks.

On April 2, a week or so after this interview, Bela and Toumani had a long public chat over Facebook. They took questions from listeners and reflected on their experiences together.