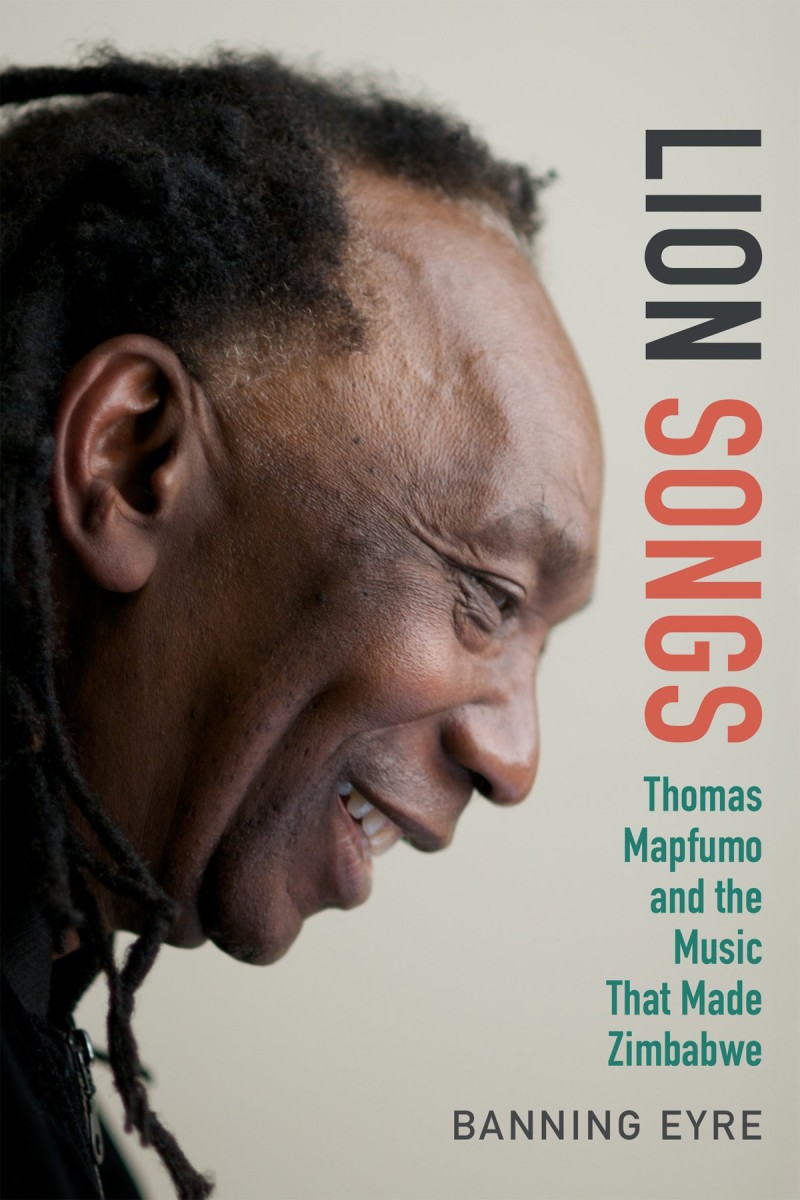

Afropop Senior Editor Banning Eyre recently published Lion Songs: Thomas Mapfumo and the Music that Made Zimbabwe, a long-awaited profile of that colossal figure in Zimbabwean music. But towering as Mapfumo may be, Zimbabwe has plenty of other musical treasure to offer. Banning picked out five tracks illuminating other (but definitely not all) aspects of Zimbabwe's fertile musical landscape, from some of Mapfumo's contemporaries. Enjoy!

The Four Brothers: “Pasi Pano Pane Zviedzo” (Makorokoto, Cooking Vinyl)

The Four Brothers were a hugely popular band in Zimbabwe, especially in the 1980s and ‘90s, both on record and within Harare's live music scene. The group was actually founded by Thomas Mapfumo’s maternal uncle, Marshall Munhumumwe, who as it happens is younger than Mafpumo. Actually, Munhumumwe is no more. He died following a stroke some years ago. But in his time, he shone brightly as the band’s drummer and lead singer.

The Four Brothers are a fine example of a small-combo Zimbabwean guitar band, the sort of act that kept folks drinking and dancing through to the wee hours in Harare’s busy beer halls and hotel ballrooms. The singing is lovely, and while I can’t shed light on the text here, you can be confident it’s not about politics. Very little Zimbabwean pop music is, one reason that Mapfumo’s brave political lyrics stand apart. But when it comes to the sheer pleasure of a tight, giddy guitar band, this is hard to beat. When you listen to the deep polyrhythmic conversation between the three guitars (including bass), you hear passages of muted, percussive playing reminiscent of Mapfumo’s mbira-inspired guitar parts. But you also hear glorious, ringing melodicism of a sort that immediately screams Zimbabwe!

Oliver Mtukudzi: “Todii” (Tuku Music, Putumayo Artists)

Oliver Mtukudzi is the only other singer/bandleader in Zimbabwe to truly count as a peer of Thomas Mapfumo. Though a few years younger, Mtukudzi has straddled the same tumultuous stretch of history, from the 1970s liberation struggle through the anguishes of the late Mugabe regime. Mtukudzi—Tuku to his fans—has never been as confrontational as Mapfumo, but that’s not to say he hasn’t engaged important issues.

This 1998 song addresses the circumstance of a person who knows he or she has HIV/AIDS. The refrain’s question “What shall we do?” is never answered, but Tuku enumerates such conundrums as mother-to-child transmission, sexual violence, and ostracism. His husky, fatherly voice in this forthright song was a tremendous comfort to Zimbabweans at a time when many people—and nearly all musicians—were afraid to address this topic openly. The song remains a staple offering in Tuku’s frequent performances around the world.

The Bhundu Boys, “Baba Munini Francis” (The Shed Sessions, Sadza Records)

The Bhundu Boys enjoyed a mercurial career during the 1980s and ‘90s. This is the stuff of legend, from the band’s dizzying rise to its tragic downfall—amid deaths from AIDS, a painful internal split, and ultimately the suicide death of singer/guitarist Biggie Tembo in 1995. The group formed in 1980 taking their name from the word for “the bush” (bhundu) where the guerrilla fighters based the country’s war of liberation. This was a tight, punchy combo—initially just five guys with deep musical chemistry to rival the Beatles. The Bhundu Boys soared to popularity, briefly surpassing both Mapfumo and Mtukudzi in record sales, and beating both elders to the prize of gigs in Europe and America.

This song captures the magic of the band’s initial formation. The song plays out the curiosity of a child who wonders why “Uncle Francis” always turns up when Daddy is away. It’s a playful take on infidelity that captures the innocence of an era before the Zimbabwean population understood the grave threat of AIDS, which would claim the lives of far too many musicians and music fans during this band’s latter years.

Chipindura Mbira Trio, “Chiyan’anya” (Pasichigare, Ingoma)

Thomas Mapfumo’s music is often associated with the Shona people’s spiritual tradition, and especially the metal-pronged mbira, a hand-held lamellophone used in spirit possession ceremonies. In the late 1980s, Mapfumo moved beyond guitar and keyboard imitations of the instrument and introduced traditional mbira players into the lineup of his band the Blacks Unlimited. One of the most important and influential of these traditional musicians was Chartwell Dutiro. After contributing to some of Mapfumo’s most successful and acclaimed recordings and performances, Dutiro moved to the U.K. to study and pursue his own career as a teacher and artist.

This recording comes from a 2013 trio recording made in Germany. It is a superb example of this tradition. The choral vocals are unusual, a mark of Dutiro’s particular creativity. But the melodies and textures here are deeply authentic, and the lyrics provide a wonderful example of what is sometimes called “deep Shona,” enigmatic expressions whose meanings are far from obvious. An example: “Those with big belly buttons should not walk in the fields. They cause lots of ant hills.”

Leonard Dembo and Barura Express, “Chitekete” (The Very Best of Leonard Dembo, Gramma)

Despite all the international attention that has gone to pioneers like Mapfumo and Mtukudzi, and to Shona mbira music, the biggest selling pop music in Zimbabwe is a giddy guitar-driven dance style called sungura. The word means “rabbit” in Swahili, and on one level, sungura is a refraction of Congolese music, filtered through East Africa. Part of the story is that fighters in the liberation war brought this music, and its associated dances, home with them after moving to East Africa to support the struggle.

This is party music, featuring feisty electric guitar interplay, pumping bass, a straight up four-on-the-floor beat, sweet vocals, and long instrumental breakdowns. It’s dance music, and many stars in the genre have their own signature moves. Sungura songs are full of ribald love stories and largely devoid of politics or challenging social commentary. This song, by one of the genre’s late legends, talks about the obstacles to marriage for a young man without money. Although it’s really about the pain of guy who can’t marry, this early ‘90s number was ubiquitous at Zimbabwean weddings for most of that decade.